module 53 Landfills and Incineration

568

Beginning in the 1930s in the United States, as public opposition to open dumps was growing, the most convenient locations for disposal of MSW became holes in the ground created by the removal of soil, sand, or other earth material that was then used for construction purposes. When people filled those holes with waste, the sites became known as landfills. Though open dumps are now rare in developed countries, they still exist in the developing world, where they pose a considerable health hazard.

In this module, we will examine the basic design and implementation of landfills and incinerators in the United States.

Learning Objectives

After reading this module, you should be able to

describe the goals and function of a solid waste landfill.

explain the design and purpose of a solid waste incinerator.

Landfills are the primary destination for MSW

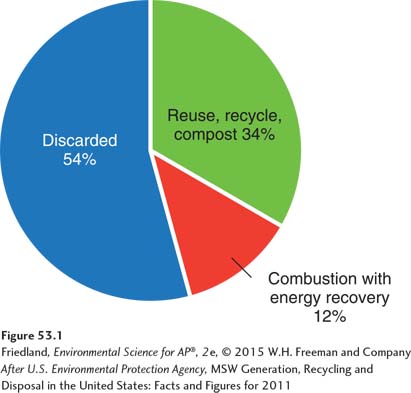

As FIGURE 53.1 shows, in the United States a third of our waste is recovered through reuse and recycling, while more than half is discarded. The remainder is converted into energy through incineration. In the United States, MSW that is not diverted from the waste stream ends up becoming either buried in landfills or incinerated.

Leachate Liquid that contains elevated levels of pollutants as a result of having passed through municipal solid waste (MSW) or contaminated soil.

Initially, there were few concerns about what material went into a landfill. Those responsible for collecting and disposing of solid waste in landfills did not recognize the many problems associated with landfills, such as components of the MSW generating harmful runoff and leachate. Leachate is the water that leaches through the solid waste and removes various chemical compounds with which it comes into contact. Nor did they recognize the harm a landfill could cause when it was located near sensitive features of the landscape such as aquifers, rivers, streams, drinking-

569

Today, some environmental scientists believe we should not use landfills at all; in later sections of this chapter we will discuss alternative means of waste disposal. Although landfills are still a component of solid waste management in the United States, we can make them much less harmful than they have been in the past. In this section we will examine landfill basics, how a landfill is sited, and the problems of using landfills.

Landfill Basics

Many people believe that a great deal of biological and chemical activity occurs in landfills. They imagine that organic matter breaks down and that landfills shrink over time as the material in them is converted into carbon dioxide or methane and released to the atmosphere. Professor William Rathje, from the University of Arizona, has challenged these misconceptions by using archaeological tools to examine modern-

Sanitary landfill An engineered ground facility designed to hold municipal solid waste (MSW) with as little contamination of the surrounding environment as possible.

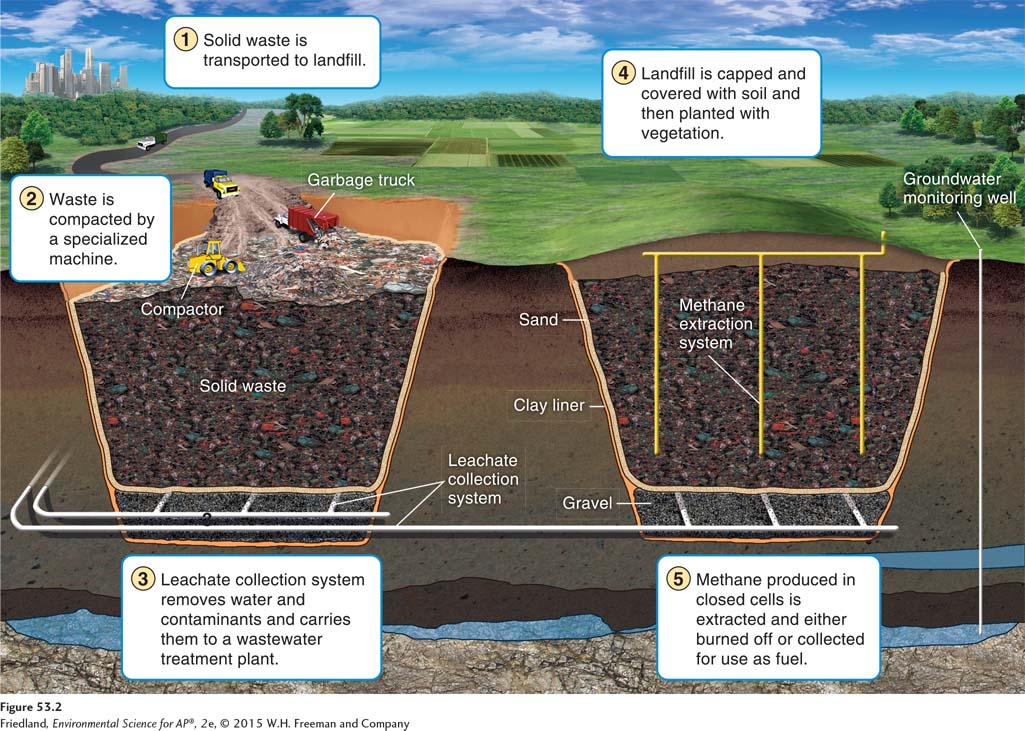

Given the lack of decomposition that occurs in a landfill, design and construction must proceed with care. In the United States today, repositories for MSW, known as sanitary landfills, are engineered ground facilities designed to hold MSW with as little contamination of the surrounding environment as possible. These facilities, like the one illustrated in FIGURE 53.2, generally utilize a variety of technologies that safeguard against the problems of traditional dumps.

570

Sanitary landfills are constructed with a clay or plastic lining at the bottom. Clay is often used because it can impede water flow and retain positively charged ions, such as metals. A system of pipes is constructed below the landfill to collect leachate, which is sometimes recycled back into the landfill. Finally, a cover of soil and clay, called a cap, is installed when the landfill reaches capacity.

Rainfall and other water inputs are minimized because excess water in the landfill causes a greater rate of anaerobic decomposition and consequent methane release. Also, with a large amount of water entering the landfill from both MSW and rainfall, there is a greater likelihood that some of that water will leave the landfill as leachate. Leachate that is not captured by the collection system may leach into nearby soils and groundwater. Leachate is tested regularly for its toxicity and if it exceeds certain toxicity standards, the landfill operators could be required to collect it and treat it as a toxic waste.

Once the landfill is constructed, it is ready to accept MSW. Perhaps the most important component of operating a safe modern-

The MSW added to a landfill is periodically compacted into “cells,” which reduce the volume of solid waste, thereby increasing the capacity of the landfill. The cells are covered with soil, which minimizes the amount of water that enters them and so reduces odor. When a landfill is full, it must be closed off from the surrounding environment so the input and output of water are reduced or eliminated. Once a landfill is closed and capped, the MSW within it is entombed. Some air and water may enter from the outside environment, but this should be minimal if the landfill was well-

Tipping fee A fee charged for disposing of material in a landfill or incinerator.

A municipality or private enterprise constructs a landfill at a tremendous cost. These costs are recovered by charging a fee for waste delivered to the landfill, called a tipping fee because each truckload is put on a scale and, after the MSW is weighed, it is tipped into the landfill. Tipping fees at solid waste landfills average $50 per ton in the United States, although in certain regions, such as the Northeast, fees can be twice that much. These fees create an economic incentive to reduce the amount of waste that goes to the landfill. Many localities accept recyclables at no cost but charge for disposal of material destined for a landfill. This practice encourages individuals to separate recyclables. Some localities mandate that recyclable material be removed from the waste stream and disposed of separately. However, if tipping fees become too high, and regulations too stringent, a locality may inadvertently encourage illegal dumping of waste materials in locations other than the landfill and recycling center.

571

Choosing a Site for a Sanitary Landfill

Siting The designation of a landfill location, typically through a regulatory process involving studies, written reports, and public hearings.

Many considerations go into siting a landfill, which means designating its location. A landfill should be located in a soil rich in clay to reduce migration of contaminants. It should be located away from rivers, streams, and other bodies of water and drinking-

A landfill siting is always highly controversial and sometimes politically charged. Because landfills are unsightly and smell bad they are not considered desirable neighbors. Landfill siting has been the source of considerable environmental injustice. People with financial resources or political influence often adopt what has been popularly called a “not-

In Fort Wayne, Indiana, for example, the Adams Center Landfill was located in a densely populated, low-

Environmental Consequences of Landfills

Though sanitary landfills, as we have seen, are an improvement over open dumps, they present many problems. Locating landfills near populations that do not have the resources to object is a global problem. No matter how careful the design and engineering, there is always the possibility that leachate from a landfill will contaminate underlying and adjacent waterways. The EPA estimates that virtually all landfills in the United States have had some leaching. Even after a landfill is closed, the potential to harm adjacent waterways remains. The amount of leaching, the substances that have leached out, and how far they will travel are impossible to know in advance. To get an idea of how much leachate is generated from a landfill and how much might be collected, see “Do the Math: How Much Leachate Might Be Collected?” on page 571.

The risk to humans and ecosystems from leachate is uncertain. Public perception is that landfill contaminants pose a great threat to human health, though the EPA has ranked this risk as fairly low compared with other risks such as global climate change and air pollution. But methane and other organic gases generated from decomposing organic material in landfills do release greenhouse gases.

When solid waste is first placed in a landfill, some aerobic decomposition may take place, but shortly after the waste is compacted into cells and covered with soil, most of the oxygen is used up. At this stage, anaerobic decomposition begins, a process that generates methane and carbon dioxide—

Incineration is another way to treat waste materials

572

Incineration The process of burning waste materials to reduce volume and mass, sometimes to generate electricity or heat.

Given all the problems of landfills, people have turned to a number of other means of solid waste disposal, including incineration. Incineration is the process of burning waste materials to reduce their volume and mass and, sometimes, to generate electricity or heat. More than three-

Incineration Basics

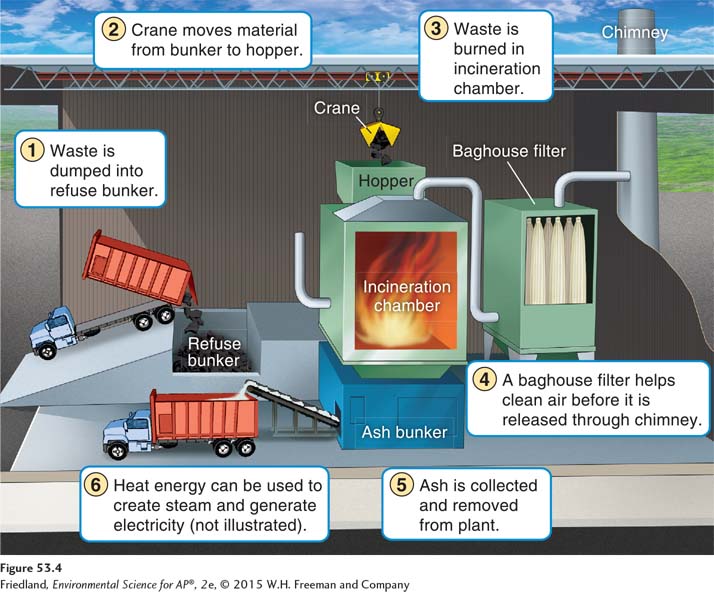

FIGURE 53.4 shows a mass-

Ash The residual nonorganic material that does not combust during incineration.

Bottom ash Residue collected at the bottom of the combustion chamber in a furnace.

Fly ash The residue collected from the chimney or exhaust pipe of a furnace.

Particulates, more commonly known as ash in the solid waste industry, are an end product of combustion. Ash is the residual nonorganic material that does not combust during incineration. Residue collected underneath the furnace is known as bottom ash and residue collected beyond the furnace is called fly ash.

Because incineration often does not operate under ideal conditions, ash typically fills roughly one-

Metals and other toxins in the MSW may be released to the atmosphere or may remain in the ash, depending on the pollutant, the specific incineration process, and the type of technology used. Exhaust gases from the combustion process, such as sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides, move through collectors and other devices that reduce their emission to the atmosphere. These collectors are similar in design to those described in Chapter 15 on air pollution. Acidic gases such as hydrogen chloride (HCl), which results from the incineration of certain materials including plastic, are recovered in a scrubber, neutralized, and sometimes treated further before disposal in a regular landfill or ash landfill.

573

Waste-

Incineration also releases a great deal of heat energy, which is often used in a boiler immediately adjacent to the furnace either to heat the incinerator building or to generate electricity, using a process similar to that of a coal, natural gas, or nuclear power plant. When heat generated by incineration is used rather than released to the atmosphere, it is known as a waste-

Environmental Consequences of Incineration

Though incinerators address some of the problems of landfills, they also have shortcomings. To cover the costs of construction and operation, incineration facilities also charge tipping fees. Tipping fees are generally higher at incinerators than at landfills; national averages are around $70 per U.S. ton. We have seen that an incinerator may release air pollutants such as organic compounds from the incomplete combustion of plastics and metals contained in the solid waste that was burned. Some environmental scientists believe that incinerators are a poor solution to solid waste disposal because they produce ash that is more concentrated and thus more toxic than the original MSW. Therefore, the siting of an incinerator raises NIMBY and environmental justice issues similar to those of landfill siting.

In addition, because incinerators are typically large and expensive to build and operate, they require large quantities of MSW on a daily basis in order to burn efficiently and to be profitable. As a means of supporting these costs, communities that use incinerators may be less likely to encourage recycling. One solution is to use rate structures and other programs to encourage MSW reduction and diversion, with the goal of using incineration only as a last resort. However, in order to be successful, this usually must be a community effort.

Incinerators may not completely burn all the waste deposited in them. Plant operators can monitor and modify the oxygen content and temperature of the burn, but because the contents of MSW are extremely variable and lumped all together, it is difficult to have a uniform burn. Consider a truckload of MSW from your neighborhood. The same load may contain food waste with high moisture content and, right next to that, packaging and other dry, easily burnable material. It is difficult for any incinerator—

574

Inevitably, MSW contains some toxic material. The concentration of toxics in MSW is generally quite low relative to all the paper, plastic, glass, and organics in the waste. However, rather than being dissipated to the atmosphere, most metals remain in the bottom ash or are captured in the fly ash. As we have already mentioned, incinerator ash that is deemed toxic must be disposed of in a special landfill for toxic materials.

As we have seen, there is no ideal choice for waste disposal. Sometimes the decision between whether to construct a landfill or build an incinerator is in part a decision about the kind of pollution a community prefers. The best choice is the production of less material for either the landfill or the incinerator.