module 54 Hazardous Waste

575

When solid waste material is deemed toxic or otherwise harmful to people or natural ecosystems, it should not be placed in a MSW landfill or incinerated. In these cases, special means of handling and disposal are required. In this module we will discuss the proper treatment of hazardous waste and some of the legislation concerning it.

Learning Objectives

After reading this module, you should be able to

define hazardous waste and discuss the issues involved in handling it.

describe regulations and legislation regarding hazardous waste.

Hazardous waste requires proper handling and disposal

Hazardous waste Liquid, solid, gaseous, or sludge waste material that is harmful to humans or ecosystems.

Hazardous waste is liquid, solid, gaseous, or sludge waste material that is harmful to humans or ecosystems. According to the EPA in 2011, over 16,000 hazardous waste generators in the United States produce about 34 million metric tons (38 million U.S. tons) of hazardous waste each year. Only about 4 percent of that waste is recycled. The majority of hazardous waste is the by-

Most municipalities do not have regular collection sites for hazardous waste or household hazardous waste. Rather, homeowners and small businesses are asked to keep their hazardous waste in a safe location until periodic collections are held (FIGURE 54.1). Every aspect of the treatment and disposal of hazardous waste is more expensive and more difficult than the disposal of ordinary MSW. Households are filled with numerous substances, such as oil-

576

Collection sites are designated as hazardous waste collection facilities that must be staffed with specially trained personnel. Sometimes the materials gathered are unlabeled and unknown and must be treated with extreme caution. Ultimately, the wastes may be sorted into a number of categories, such as fuels, solvents, and lubricants, for example. Some items, such as paint, may be reused, while others may be sent to a special facility for treatment.

As with other waste, there are no truly good options for disposing of hazardous waste. Source reduction is the most beneficial and one of the least expensive ways to approach hazardous waste: Don’t create the waste in the first place. In the case of household hazardous waste, many community groups and municipalities encourage consumers to substitute products that are less toxic or to use as little of the toxic substances as possible.

Legislation oversees and regulates the treatment of hazardous waste

Because of the dangers that hazardous waste presents, disposal has received much public attention. At times in the past few decades, hazardous waste sites have become commonly known household names. Because lawmakers and the general public have mandated that hazardous waste be regulated, there are a number of laws and acts that specifically cover hazardous waste. We will discuss two of them in this section.

Regulation and Oversight of Handling Hazardous Waste

Regulation and handling of hazardous waste in the United States falls under two pieces of federal legislation, the U.S. Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) and the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA).

In 1976, RCRA expanded previous solid waste laws. Its main goal was to protect human health and the natural environment by reducing or eliminating the generation of hazardous waste. Under RCRA’s provision for “cradle-

Superfund Act The common name for the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA); a 1980 U.S. federal act that imposes a tax on the chemical and petroleum industries, funds the cleanup of abandoned and nonoperating hazardous waste sites, and authorizes the federal government to respond directly to the release or threatened release of substances that may pose a threat to human health or the environment.

CERCLA, usually referred to as the Superfund Act, is a 1980 U.S. federal act that imposes a tax on the chemical and petroleum industries, funds the cleanup of abandoned and nonoperating hazardous waste sites, and authorizes the federal government to respond directly to the release or threatened release of substances that may pose a threat to human health or the environment. The Superfund Act is well known because of a number of sensational cases that have fallen under its jurisdiction. Originally passed in 1980 and amended in 1986, this legislation has several parts. First, it imposes a tax on the chemical and petroleum industries. The revenue from this tax is used to fund the cleanup of abandoned and nonoperating hazardous waste sites where a responsible party cannot be established. The name Superfund came from this provision. CERCLA also authorizes the federal government to respond directly to the release or threatened release of substances that may pose a threat to human health or the environment.

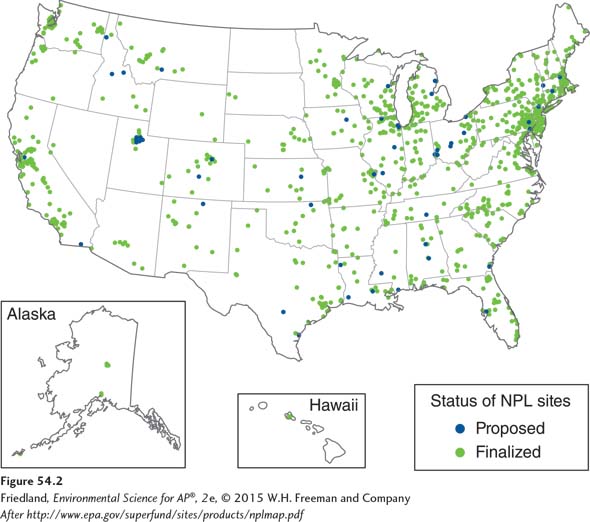

Under Superfund, the EPA maintains the National Priorities List (NPL) of contaminated sites that are eligible for cleanup funds. For a long time, very little Superfund money was disbursed and few sites underwent remediation. The map in FIGURE 54.2 shows the location of the NPL sites. As of mid-

Perhaps the best-

577

Since its inception, many have observed that CERCLA has not had enough funding to clean up the numerous hazardous waste sites around the country. The listing of NPL sites in a state does not necessarily include all contaminated sites within that state. For example, the Department of Environmental Protection in New Jersey, a state that has approximately 113 listed Superfund sites, believes that there are more than 9,000 sites where soil or groundwater is contaminated with hazardous chemicals.

Brownfields

Brownfields Contaminated industrial or commercial sites that may require environmental cleanup before they can be redeveloped or expanded.

The Superfund designation is reserved strictly for those locations with the highest risk to public health, and Superfund sites are managed solely by the federal government. In 1995, the EPA created the Brownfields Program. Brownfields, like Superfund sites, are contaminated industrial or commercial sites that may require environmental cleanup before they can be redeveloped or expanded. The Brownfields Program assists state and local governments in cleaning up contaminated industrial and commercial land that did not achieve conditions necessary to be in the Superfund category. Old factories, industrial areas and waterfronts, dry cleaners, gas stations, landfills, and rail yards are common examples of brownfield sites. Brownfields legislation has prompted the revitalization of several sites throughout the country. One notable instance is Seattle’s Gasworks Park. In 1962, the city of Seattle purchased the land, which had housed a coal gasification plant, to rehabilitate the site into a park. After undergoing chemical abatement and environmental cleanup, the park has become a distinctive landmark for the city and is the site of many public events throughout the year.

The Brownfields Program has been criticized as an inadequate solution to the estimated 450,000 contaminated locations throughout the country. Since the cleanup is managed entirely by state and local governments, brownfields management can vary widely from region to region. Furthermore, the brownfields legislation lacks legal liability controls to compel polluters to rehabilitate their properties. Without legal recourse, many brownfield sites remain unused and contaminated, posing a continued risk to public health.

578

International Consequences

Because of the difficulties involved in disposing of hazardous waste, municipalities and industries sometimes try to send the waste to countries with less stringent regulations. There are numerous reports of garbage and ash barges that travel the oceans looking for a developing country willing to accept hazardous waste from the United States in exchange for a cash payment. Perhaps the most famous is the story of the cargo vessel Khian Sea, which left Philadelphia in 1986 with almost 13,000 metric tons of hazardous ash from an incinerator. It traveled to a number of countries in the Caribbean in search of a dumping place. Some of the ash was dumped in Haiti, and some was dumped in the ocean. In 1996, the United States ordered that the ash dumped in Haiti be retrieved and returned to the United States. After being held at a dock in Florida, the ash was deemed nonhazardous by the EPA and other agencies and in 2002, the ash was placed in a landfill in Franklin County, Pennsylvania, not very far from its source of origin.

In 2003, a notable instance of a waste transfer in the other direction occurred. A Pennsylvania company that specializes in recovering mercury from a wide variety of products agreed to accept 270 metric tons of mercury waste generated by a company in the state of Tamil Nadu, India, during the manufacture of thermometers. India had no facilities for recycling mercury waste, and most of the thermometers manufactured at the plant were shipped to the United States and Europe, so the transfer of material seemed appropriate. The mercury was shipped from India to the United States, where the mercury was concentrated, purified, and then sold to industrial users of the metal.

There are currently incinerator operators in Vancouver, British Columbia; Plymouth, England; and elsewhere around the world that are seeking appropriate disposal sites for their ash, but they seem to have stopped looking for other countries to accept this material. Most incinerator operators are now identifying closer locations for ash disposal.