module 56 Human Disease

591

Humans face a wide range of potential diseases. In this module, we will explore different types of diseases and discuss the risk factors that make some people more likely to contract diseases. We will then discuss a number of diseases that have been important in human history as well as the diseases that have become prevalent in recent decades.

Learning Objectives

After reading this module you should be able to

identify the different types of human diseases.

understand the risk factors for human chronic diseases.

discuss the historically important human diseases.

identify the major emergent infectious diseases.

discuss the future challenges for improving human health.

There are different types of human diseases

Disease Any impaired function of the body with a characteristic set of symptoms.

Infectious disease A disease caused by a pathogen.

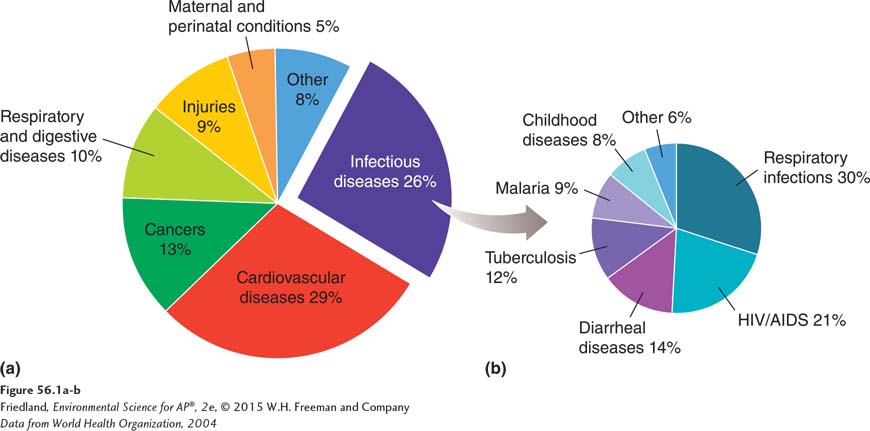

Of all causes of human deaths worldwide, which are shown in FIGURE 56.1, approximately three-

The pathogens that cause most infectious diseases include viruses, bacteria, fungi, protists, and a group of parasitic worms called helminths. However, only six types of disease cause 94 percent of all deaths attributed to infectious diseases. The three most common types of infectious disease are AIDS, diseases that cause respiratory infections, and diarrheal diseases. The next three are tuberculosis, malaria, and childhood diseases such as measles and tetanus. We will discuss many of these important infectious diseases later in the chapter.

Acute disease A disease that rapidly impairs the functioning of an organism.

Chronic disease A disease that slowly impairs the functioning of an organism.

All diseases can also be categorized as either acute or chronic. Acute diseases rapidly impair the functioning of a person’s body. In some cases, such as a disease called Ebola hemorrhagic fever that we will discuss later in this chapter, death can come in a matter of days or weeks. In contrast, chronic diseases slowly impair the functioning of a person’s body. Heart disease and most cancers, for example, are chronic diseases that develop over several decades.

Numerous risk factors exist for chronic disease in humans

592

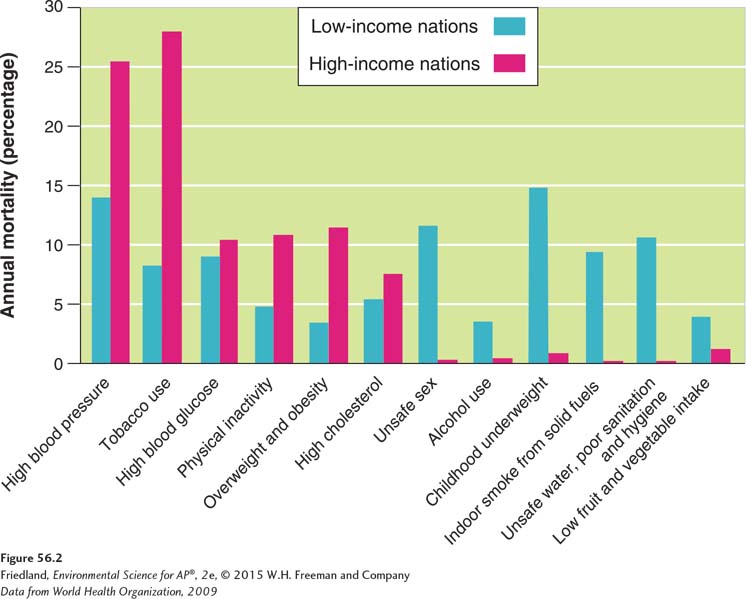

Numerous factors cause people to be at a greater risk for chronic diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and chronic infectious diseases. The World Health Organization (WHO) has found that these risk factors differ substantially between low-

In low-

593

Affluence changes the major health risk factors for chronic disease. Because people in high-

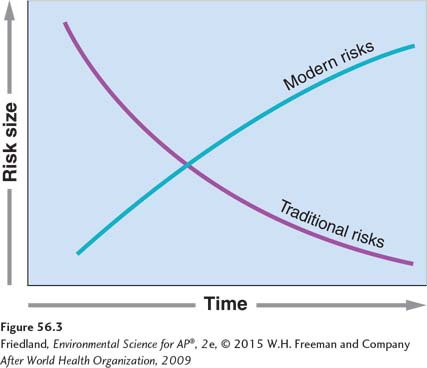

The change in risk factors between low-

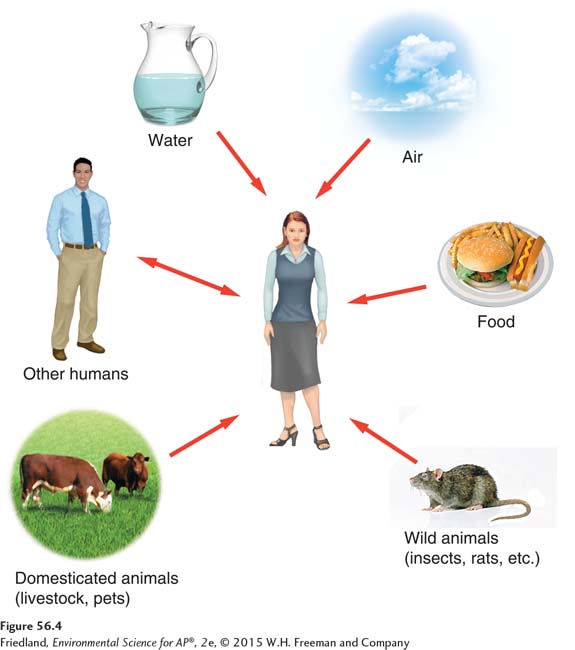

Some infectious diseases have been historically important

Although diseases can have genetic causes, environmental scientists are generally interested in diseases that have environmental causes, especially those caused by pathogens such as fungi, bacteria, and viruses. These pathogens have evolved a wide variety of pathways for infecting humans, including transmission through food, water, other humans, and other animals. FIGURE 56.4 illustrates some of these relationships.

Epidemic A situation in which a pathogen causes a rapid increase in disease.

Pandemic An epidemic that occurs over a large geographic region.

Historically, disease-

Plague

Plague An infectious disease caused by a bacterium (Yersinia pestis) that is carried by fleas.

594

Plague is caused by an infection from a bacterium (Yersinia pestis) that is carried by fleas. Fleas attach to rodents such as mice and rats, which gives the fleas tremendous mobility. One of the most well-

Malaria

Malaria An infectious disease caused by one of several species of protists in the genus Plasmodium.

Malaria, caused by an infection from any one of several species of protists in the genus Plasmodium, is another widespread disease that has killed millions of people over the centuries. The malaria parasite spends one stage of its life inside a mosquito and another stage of its life inside a human. Infections cause recurrent flulike symptoms. Each year, 350 to 500 million people in the world contract the disease and 1 million people, mostly children under 5 years of age, die from it. The regions hardest hit include sub-

The traditional approach to combating malaria was widespread spraying of insecticides such as DDT to eradicate the mosquitoes. Eradication efforts have proven to be ineffective in many parts of the world. Moreover, as we will see later in this chapter, the widespread use of many insecticides can create new problems. At the end of this chapter, “Working Toward Sustainability: The Global Fight Against Malaria” on page 618 examines the latest approaches toward combating malaria.

Tuberculosis

595

Tuberculosis A highly contagious disease caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis that primarily infects the lungs.

Tuberculosis is a highly contagious disease caused by a bacterium (Mycobacterium tuberculosis) that primarily infects the lungs. Tuberculosis is spread when a person coughs and expels the bacteria into the air. The bacteria can persist in the air for several hours and infect a person who inhales them. Symptoms of an infection include feeling weak, sweating at night, and coughing up blood. As is the case with many pathogens, a person can be infected but not develop the tuberculosis disease. Indeed, it is estimated that one-

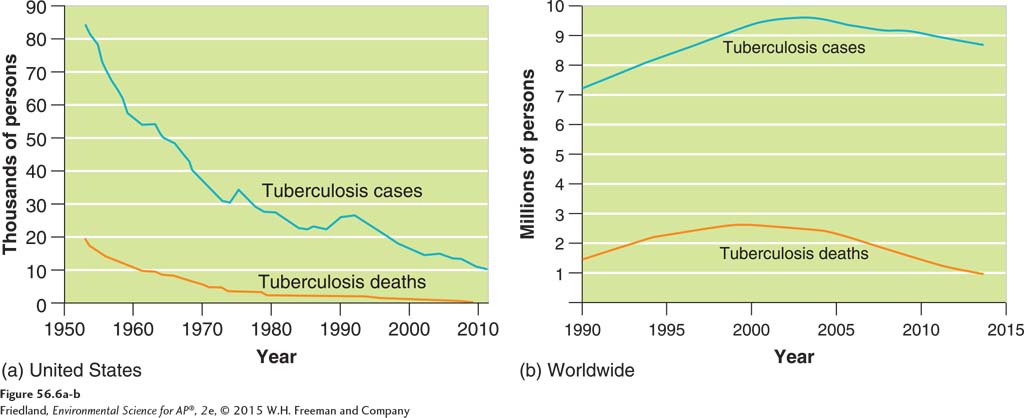

Taking antibiotics for a year can easily treat most tuberculosis infections. In countries such as the United States, where such medicines are readily available, there has been a dramatic drop in both the number of new cases and the number of deaths from tuberculosis. FIGURE 56.6 shows the decline of tuberculosis in the United States since the mid-

Emergent infectious diseases pose new risks to humans

Emergent infectious disease An infectious disease that has not been previously described or has not been common for at least 20 years.

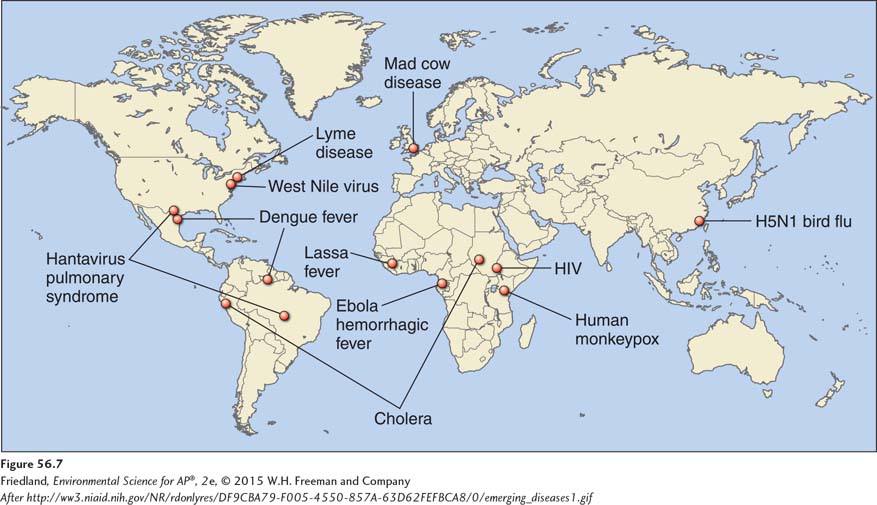

In recent decades, we have witnessed the appearance of many emergent infectious diseases, which are defined as infectious diseases that were previously not described or have not been common for at least the prior 20 years. FIGURE 56.7 locates some of the best known emergent infectious diseases. Since the 1970s, the world has observed an average of one emergent disease each year. Many of these new diseases have come from pathogens that normally infect animal hosts but then unexpectedly jump to human hosts. This typically occurs because the diseases can mutate rapidly and eventually produce a genotype that can infect humans. Some of the most high-

596

HIV/AIDS

Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) An infectious disease caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) A type of virus that causes Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS).

In the late 1970s, rare types of pneumonia and cancer began appearing in individuals with weak immune systems. The condition responsible for the weakened immune systems was the disease Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS), which is caused by a virus known as Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). This virus spreads through sexual contact and blood transfusions, from mothers who pass it on to their fetuses, and among drug users who share unsanitized needles.

The origin of this new virus remained a mystery until 2006 when researchers found a genetically similar virus in a wild population of chimpanzees living in the African nation of Cameroon (FIGURE 56.8). The researchers hypothesized that local hunters were exposed to the virus when butchering or eating the chimps (a common practice in this part of the world). With this exposure, the virus was able to infect a new host, humans. Today, more than 33 million people in the world are infected with HIV and 25 million people have died from AIDS-

Fortunately, new antiviral drugs are able to maintain low HIV populations inside the human body and thereby substantially extend life. From the lessons learned in combating other diseases such as tuberculosis, combinations of antiviral drugs are being used to reduce the risk that the virus will evolve resistance to any single drug. Unfortunately, many of these drugs are expensive and most people living in low-

Ebola Hemorrhagic Diseases

Ebola hemorrhagic fever An infectious disease with high death rates, caused by the Ebola virus.

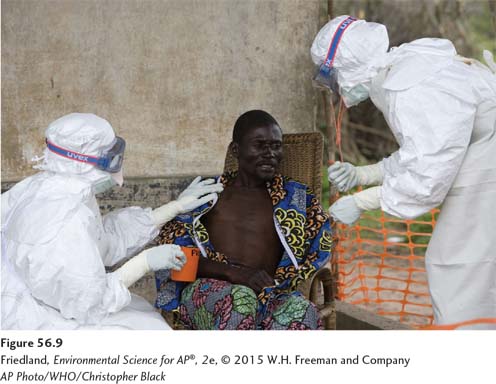

In 1976, researchers first discovered Ebola hemorrhagic fever, an infectious disease with high death rates, caused by the Ebola virus. First discovered in the Democratic Republic of the Congo near the Ebola River, the virus has infected several hundred humans and a variety of other primates from several countries in central Africa. Infections have been sporadic since Ebola was first discovered, but there was a large outbreak in 2014 that infected thousands of people. The Ebola virus is of particular concern because it kills a large percentage of those infected. Infected individuals have suffered a 50 to 89 percent death rate from different outbreaks of the disease. Those infected quickly begin to experience fever, vomiting, and sometimes internal and external bleeding (FIGURE 56.9). Death occurs within 2 weeks, and currently only experimental drugs are available to fight the virus. Unlike the progress that has been made with identifying the origin of HIV, the natural source of the Ebola virus has been difficult to determine. Because the virus also kills other primates at high rates, leaving no primate hosts for the virus, primates are not a likely long-

597

Mad Cow Disease

Mad cow disease A disease in which prions mutate into deadly pathogens and slowly damage a cow’s nervous system.

Prion A small, beneficial protein that occasionally mutates into a pathogen.

In the 1980s, scientists first described a neurological disease, later known as mad cow disease, in which prions mutate into deadly pathogens and slowly damage a cow’s nervous system. The cow loses coordination of its body (a condition compared with a person going mad), and then dies (FIGURE 56.10). Scientists now know that small, beneficial proteins in brains of cattle, called prions, occasionally mutate into deadly proteins that act as pathogens and subsequently cause mad cow disease. Prions are not well understood and represent a new category of pathogen.

In 1996, scientists in Great Britain announced that mad cow disease, also known as bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), could be transmitted to humans who ate meat from infected cattle. Unlike harmful bacteria that can be killed with proper cooking, prions are difficult to destroy by cooking. Infected humans developed variant Creutzfeldt-

598

Mutant prions cannot be transmitted among cattle that only live together. Transmission requires an uninfected cow to consume the nervous system of an infected cow. As a result, when cattle feed on grass together in a pasture, a rare mutation in a prion would be restricted to a single cow and not spread to other cattle. In the 1980s, however, the diets of European cattle commonly included the ground-

Swine Flu and Bird Flu

Swine flu A type of flu caused by the H1N1 virus.

Humans commonly contract many types of flu viruses. As we saw in Chapter 5, the Spanish flu of 1918 killed up to 100 million people. Spanish flu was a type of influenza, known as swine flu, caused by the H1N1 virus. This virus is similar to a flu virus that humans normally contract, but H1N1 normally infects only pigs. Another pandemic of swine flu occurred around the world in 2009–

Bird flu A type of flu caused by the H5N1 virus.

In 2006, reports emerged from Asia that a related virus, known as H5N1, or bird flu, had jumped from birds to people, primarily to people who were in close contact with birds (FIGURE 56.11). Infections are rarely deadly to wild birds but can frequently cause domesticated birds such as ducks, chickens, and turkeys to become very sick and die. Humans often contract a variety of flu viruses. Because humans have no evolutionary history with the H5N1 virus, they have few defenses against it. As of 2014, more than 600 people had become infected by H5N1 and over half of them died. Governments responded to this risk by destroying large numbers of infected birds. Currently the H5N1 virus is not easily passed among people, but if a future mutation makes transmission easier, scientists estimate that H5N1 has the potential to kill 150 million people.

SARS

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) A type of flu caused by a coronavirus.

599

In 2003, an unusual form of pneumonia was spreading through human populations in Southeast Asia that was eventually named severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). While some of the respiratory symptoms are similar to bird flu and swine flu, SARS is a disease caused by a different type of virus known as a coronavirus that can spread from one person to another. During this outbreak, there were more than 8,000 people infected and nearly 10 percent of them died.

West Nile Virus

West Nile virus A virus that lives in hundreds of species of birds and is transmitted among birds by mosquitoes.

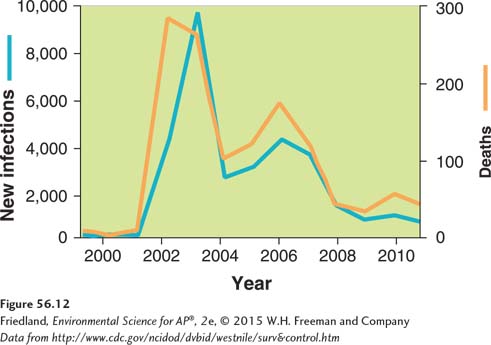

The West Nile virus lives in hundreds of species of birds and is transmitted among birds by mosquitoes. Although the virus can be highly lethal to some species of birds, including blue jays (Cyanocitta cristata), American crows (Corvus brachyrhynchos), and American robins (Turdus migratorius), most species of birds survive the infection. During the latter half of the twentieth century there were increasing reports that the virus could sometimes infect horses and humans who had been bitten by mosquitoes. The first human case was identified in 1937 in the West Nile region of Uganda, thus giving the virus its name. In humans, the virus causes an inflammation of the brain leading to illness and sometimes death. In 1999, the virus appeared in New York and quickly spread throughout much of the United States. FIGURE 56.12 shows the history of the West Nile virus in the United States. The highest numbers of infections and deaths from the virus occurred in 2002 and 2003. Increased efforts to combat mosquito populations and protect against mosquito bites are causing a decline in the disease.

Human health faces a number of future challenges

While humans face a large number of health risks, we have an excellent understanding of important risk factors and the ways to combat many historical and emerging infectious diseases. Combating diseases in low-

As we combat many diseases, an issue of growing concern is the ability of pathogens to evolve resistance. As we noted in the case of tuberculosis, patients often feel much better long before they complete the full year of prescribed medicine. Because they feel better or because they cannot afford a full year of drugs, they stop the drug treatment early. This allows a small fraction of highly resistant bacteria to survive in the body, reproduce, and then potentially spread to other people. When a pathogen evolves resistance to one drug, physicians often prescribe a different drug to combat the pathogen. Over time, however, some pathogens such as tuberculosis have evolved multiple drug resistance. Without new drugs, little can be done for patients with pathogen strains that possess multiple drug resistance.

A similar issue occurs with the increased use of antiseptic cleaners that are designed to kill microbes such as bacteria. As of 2014, there are more than 2,000 antiseptic cleaners being sold including a large number of antibacterial soaps; these products typically kill a large proportion of harmful pathogens, but not all of them. As a result of our efforts to wipe out pathogens, we are inadvertently selecting for pathogens that possess a stronger resistance to our efforts. Moreover, these products also move through wastewater and into streams, rivers, and lakes. Ironically, it is unclear that antiseptic products kill microbes any better than plain soap. Because of these concerns, in 2013 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced that they were considering new rules that would require manufacturers to conduct research to demonstrate that their antiseptic cleaners really are more effective than plain soap and water and that their products are safe for people to use on a daily basis.

600

Though many historical diseases are either currently under control or likely to be soon if the financial resources become available, emerging infectious diseases may present a greater challenge. New diseases often arise from new pathogens with which we have no experience. Since we cannot predict which diseases will emerge next, public health officials throughout the world must develop rapid response plans when a particular disease does appear. These include rapid worldwide notification of newly identified diseases and strategies to isolate infected persons, which will slow the spread of the disease and provide time for researchers to develop appropriate tactics to combat the threat.