module 61 The Conservation of Biodiversity

650

It is important that we consider how to protect and increase biodiversity because of the large number of factors that can reduce biodiversity. There are two general approaches to conserving biodiversity: the single-

Learning Objectives

After reading this module you should be able to

identify legislation that focuses on protecting single species.

discuss conservation efforts that focus on protecting entire ecosystems.

Conservation legislation often focuses on single species

The single-

The Marine Mammal Protection Act

Marine Mammal Protection Act A 1972 U.S. act to protect declining populations of marine mammals.

In the United States, the single-

651

The Endangered Species Act

Endangered species A species that is in danger of extinction within the foreseeable future throughout all or a significant portion of its range.

Threatened species According to U.S. legislation, any species that is likely to become an endangered species within the foreseeable future throughout all or a significant portion of its range.

In Chapter 10, we noted that the Endangered Species Act is a 1973 law designed to protect species from extinction. This act authorizes the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to determine which species can be listed as threatened species or endangered species and prohibits the harming of such species, including prohibitions on the trade of listed species, their fur, or their body parts. You might recall that earlier in this chapter we discussed the international definitions of threatened and near-

The Endangered Species Act was first passed in 1973 and has been amended several times since then. From an international perspective, the act also implements the international CITES agreement that we discussed in the previous module. To assist in the conservation of threatened and endangered species, the act authorizes the government to purchase habitat that is critical to the conservation of these species and to develop recovery plans to increase the population of threatened and endangered species. This is often one of the most important steps in allowing endangered species to persist.

In 2013, the species that have been listed as threatened or endangered in the United States include 227 invertebrate animals, 394 vertebrate animals, and 815 plants. An additional 245 species are currently being considered for listing, a process that can take several years. Once listed, however, many threatened and endangered species have experienced stable or increasing populations. Indeed, some species have experienced sufficient increases in numbers to be removed from the endangered species list; these include the bald eagle (FIGURE 61.2), peregrine falcon, American alligator, and the eastern Pacific population of the gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus). Other species are currently increasing in number and may be taken off the list in the future. The gray wolf, for example, was reintroduced into Yellowstone National Park to help improve the species’ abundance in the United States and it is now no longer endangered.

The Endangered Species Act has sparked a great deal of controversy in recent years because it permits restriction of certain human activities in areas where listed species live, including how landowners use their land. For example, some construction projects have been prevented or altered to accommodate threatened or endangered species. Organizations whose activities are restricted by the Endangered Species Act often try to pit the protection of listed species against the jobs of people in the region. In the 1990s, for example, logging companies wanted to continue logging the old-

652

During the past decade, several politicians have attempted to weaken the Endangered Species Act. However, strong support from the public and scientists has allowed it to retain much of its original power to protect threatened and endangered species. The biggest current challenge is a lack of sufficient funds and personnel required to implement the law.

The Convention on Biological Diversity

Convention on Biological Diversity An international treaty to help protect biodiversity.

Protection of biodiversity is an international concern. In 1992, world nations came together and created the Convention on Biological Diversity, which is an international treaty to help protect biodiversity. The treaty had three objectives: conserve biodiversity, sustainably use biodiversity, and equitably share the benefits that emerge from the commercial use of genetic resources such as pharmaceutical drugs.

In 2002, the convention developed a strategic plan to achieve a substantial reduction in the worldwide rate of biodiversity loss by 2010. The nations that signed this agreement recognized both the instrumental and intrinsic values of biodiversity. In 2010, the convention evaluated the current trends in biodiversity around the world and concluded that the goal had not been met. They identified the following trends from 2002 to 2010:

On average, species at risk of extinction have moved closer to extinction.

One-

quarter of all plant species are still threatened with extinction. Natural habitats are becoming smaller and more fragmented.

The genetic diversity of crops and livestock is still declining.

There is a widespread loss of ecosystem function.

The causes of biodiversity loss have either stayed the same or increased in intensity.

The ecological footprint of humans has increased.

Collectively, the message emerging from the convention is not very positive. From the perspectives of genetic diversity, species diversity, and ecosystem services, all of the trends during the 8-

Some conservation efforts focus on protecting entire ecosystems

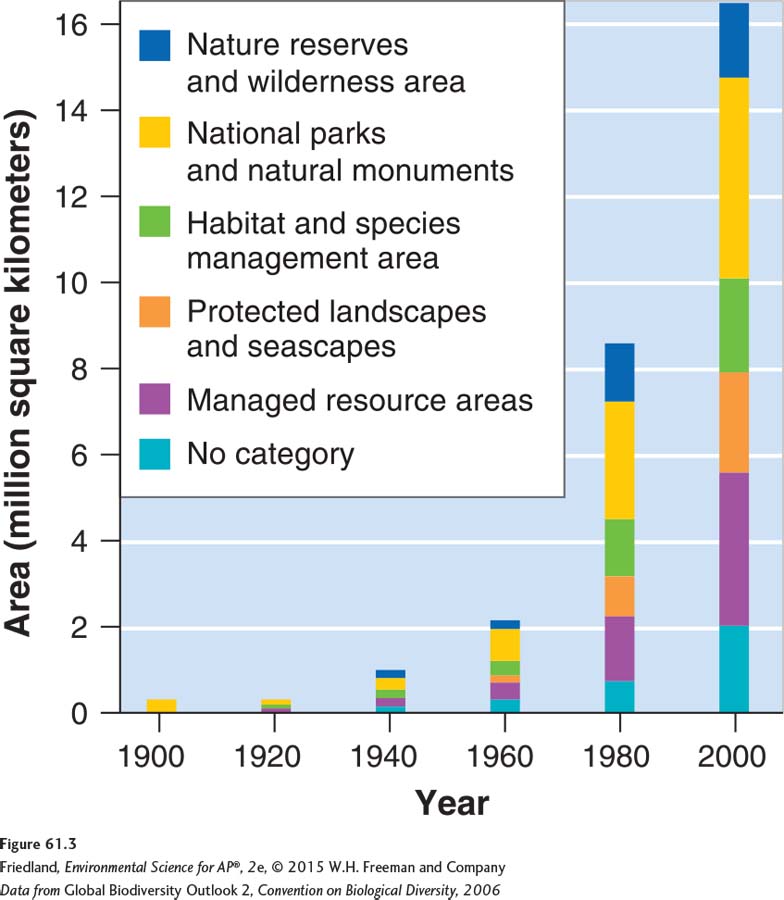

Awareness of a potential sixth mass extinction in which humans have played a major role has brought a growing interest in the ecosystem approach to conserving biodiversity. This approach recognizes the benefit of preserving particular regions of the world, such as biodiversity hotspots. Protecting entire ecosystems has been one of the major motivating factors in setting aside national parks and marine reserves. In some cases, these areas were originally protected for their aesthetic beauty, but today they are also valued for their communities of organisms. The amount of protected land has increased dramatically throughout the world since 1960. As an example of this increase, FIGURE 61.3 shows changes in the amount of protected land worldwide since 1900.

653

When protecting ecosystems to conserve biodiversity, a number of factors must be taken into consideration including the size and shape of the protected area. We must also consider the amount of connectedness to other protected areas and how best to incorporate conservation while recognizing the need for sustainable habitat use for human needs.

The Size, Shape, and Connectedness of Protected Areas

A number of questions arise when we consider protecting areas of land or water. For example, how large should the designated area be? Should we protect a single large area or several smaller areas? Does it matter whether protected areas are isolated or if they are near other protected areas? To help us answer these questions, we can return to our discussion of the theory of island biogeography from Chapter 6.

As you may recall, the theory of island biogeography looks at how the size of islands and the distance between islands and the mainland affect the number of species that are present on different islands. Larger islands generally contain more species because they support larger populations of each species, which makes them less susceptible to extinction. Larger islands also contain more species because they typically contain more habitats and, therefore, provide a wider range of niches for different species to occupy. The distance between an island and the mainland, or between one island and another, is another crucial factor, since more species are capable of dispersing to close islands than to islands farther away.

Although the theory of island biogeography was originally applied to oceanic islands, it has since been applied to islands of protected areas in the midst of less hospitable environments. For example, we can think of all the state and national parks, natural areas, and wilderness areas as islands surrounded by environments subject to high levels of human activity, including agricultural fields, logged forests, housing developments, and cities (FIGURE 61.4). These areas provide habitats for species and places to stop and rest for migrating species. Applying the theory of island biogeography from this perspective gives us some idea of the best ways to design and manage protected areas. For example, when protected areas are far apart, it is less likely that species can travel among them. This means that when a species has been lost from one ecosystem, it will be harder for individuals of that species from other ecosystems to recolonize it. So when we create smaller areas, they should be close enough for species to move among them easily.

Decisions regarding the design of protected areas can also be informed by the concept of metapopulations. As we learned in Chapter 6, a metapopulation is a collection of smaller populations connected by occasional dispersal of individuals along habitat corridors. Each population fluctuates somewhat independently of the other populations and a population that declines or goes extinct, due to a disease for example, can be rescued by dispersers from a neighboring population. So if we set aside multiple protected areas, and recognize the need for connecting habitat corridors, a species is more likely to be protected from extinction by a decimating event such as a disease or natural disaster that could eliminate all individuals in a single protected area.

Edge habitat Habitat that occurs where two different communities come together, typically forming an abrupt transition, such as where a grassy field meets a forest.

The concepts of island biogeography and metapopulations raise an interesting dilemma for conservation efforts. If we have limited resources to protect the biodiversity of a region, should we protect a single large area or several small areas? A single large area would support larger populations, but a species is more likely to survive a disease or natural disaster if it occupies several different areas. The debate over the best approach is known as SLOSS, which is an acronym for “single large or several small.” While both approaches have their merits, in reality, human development and other factors often mean that only one of the two strategies is available. For example, due to human development of a region, there may simply not be a single large area available to protect, so the only available strategy is to protect several small areas. A final consideration regarding the size and shape of protected areas is the amount of edge habitat that an area contains. Edge habitat occurs where two different communities come together, typically forming an abrupt transition, such as where a grassy field meets a forest. While some species will live in either field or forest, others, like the brown-

654

Biosphere Reserves

Biosphere reserve Protected area consisting of zones that vary in the amount of permissible human impact.

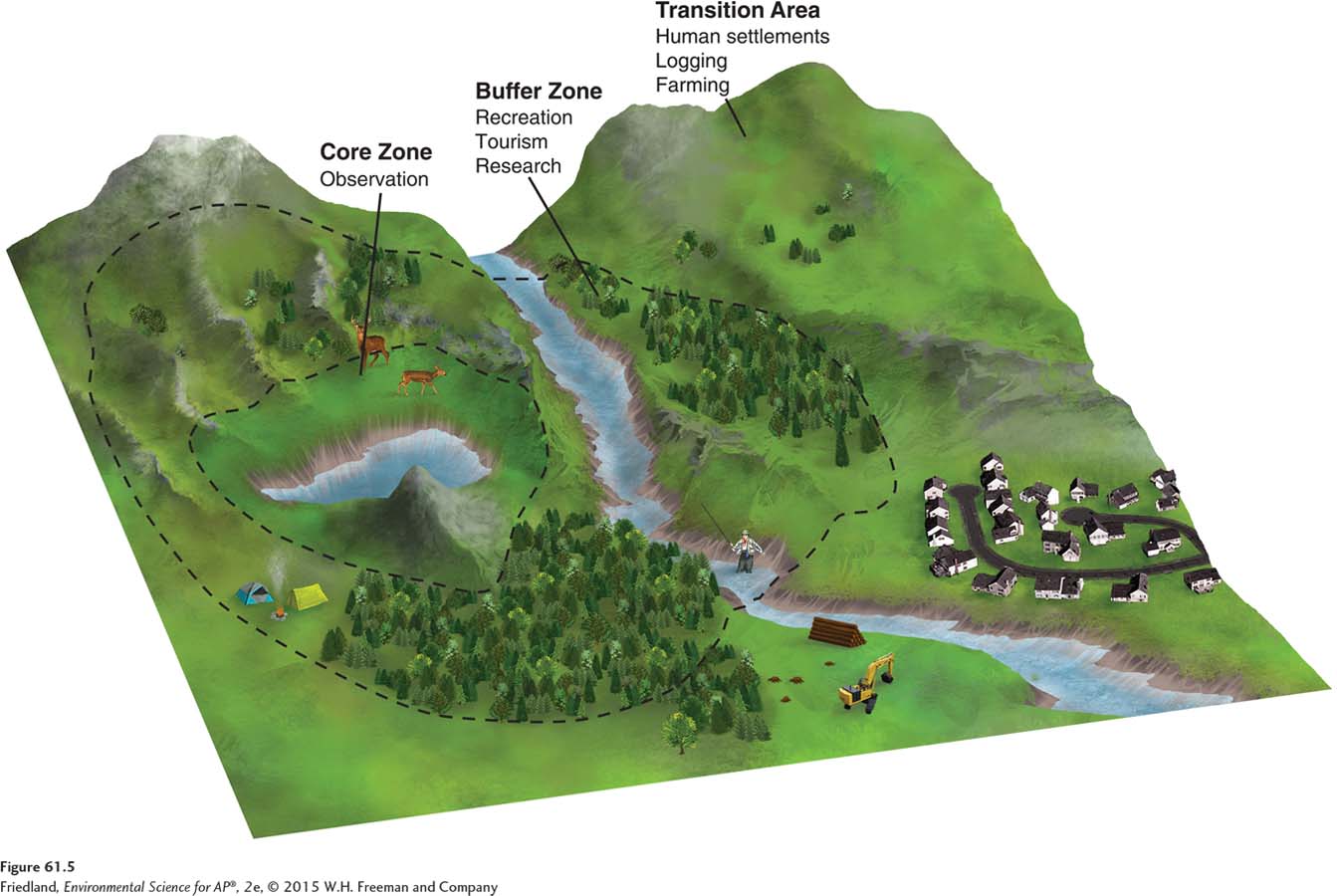

In Chapter 10 we saw that managing national parks and other protected areas so they serve multiple users can be a challenge. While we want to make places of great natural beauty available to everyone, when large numbers of people use an area for recreation, at least some degradation is very likely. To address this problem, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) developed the innovative concept of biosphere reserves. Biosphere reserves are protected areas consisting of zones that vary in the amount of permissible human impact. These reserves protect biodiversity without excluding all human activity. FIGURE 61.5 shows the different zones in a hypothetical biosphere reserve. The central core is an area that receives minimal human impact and is therefore the best location for preserving biodiversity. A buffer zone encircles the core area. Here, modest amounts of human activity are permitted, including tourism, environmental education, and scientific research facilities. Farther out is a transition area containing sustainable logging, sustainable agriculture, and residences for the local human population.

Designing reserves with these three zones represents an ideal scenario. In reality, biosphere reserves can take many forms depending on their location, though all attempt to maintain low-

655

One well-