module 66 Regulations and Equity

711

We have looked at the economic system and the roles of natural capital and human capital. This understanding provides us with the tools we need to evaluate different options for monitoring and managing human systems in a way that will result in the least amount of harm to the natural environment. Regulatory tools are also used to bring about the least environmental harm. Ultimately, the goal is freedom from exposure to environmental harm for all the people in the world. This is the final topic of the book: environmental equity.

Learning Objectives

After reading this module you should be able to

explain the role of agencies and regulations in efforts to protect our natural and human capital.

describe the approaches to measuring and achieving sustainability.

discuss the relationship among sustainability, poverty, personal action, and stewardship.

Agencies, laws, and regulations are designed to protect our natural and human capital

Many different techniques and approaches are used to influence how we treat the environment. Sometimes laws and regulations help achieve a certain outcome. Before examining some of the major laws and regulations in the United States and the world, we must familiarize ourselves with an important factor that shapes the way nations approach policy making—

Environmental Worldviews and Regulatory Approaches

We have seen that the approach a nation takes to the regulation of economic activity and the environment depends in part on that nation’s stage of development. In addition, worldview and attitude toward risk also shape a nation’s approach to economics and the environment.

Worldviews

Environmental worldview A worldview that encompasses how one thinks the world works; how one views one’s role in the world; and what one believes to be proper environmental behavior.

An environmental worldview is a worldview that encompasses how one thinks the world works; how one views his or her role in the world; and what one believes to be proper environmental behavior. Three types of environmental worldviews dominate: human-

712

Anthropocentric worldview A worldview that focuses on human welfare and well-

Stewardship The careful and responsible management and care for Earth and its resources.

The anthropocentric worldview is a worldview that focuses on human welfare and well-

Biocentric worldview A worldview that holds that humans are just one of many species on Earth, all of which have equal intrinsic value.

The biocentric worldview is life-

Ecocentric worldview A worldview that places equal value on all living organisms and the ecosystems in which they live.

The ecocentric worldview is Earth-

Environmental worldviews can play a significant role in the policies a nation considers and how it implements them. For example, a nation that operates on an anthropocentric worldview might not concern itself with how economic activity affects the natural environment. A country with an ecocentric worldview might carefully regulate economic activity in order to protect ecosystems and the species within them. In practice, the policies and regulations of most nations represent a variety of worldviews depending on the particular nation and the specific resource or region of the biosphere that is being affected.

The Precautionary Principle

A nation’s approach to environmental policy and regulation may also be influenced by whether or not it tends to follow the precautionary principle. In Chapter 17 we discussed the precautionary principle, which states that when the results of an action are uncertain—

Critics of the precautionary principle maintain that economic progress and human well-

In 1994, the International Union for Conservation of Nature, an organization composed of over 800 government and nongovernmental wildlife organizations, strengthened the 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity by publishing guidelines that included applying the precautionary principle as a tool in reaching decisions about the sustainable use of plant and animal species. The guidelines emphasize using the “best science available” in deciding whether to list a species as endangered and whether to ban any activity that could jeopardize that species.

The 1987 Montreal Protocol on Substances That Deplete the Ozone Layer is an example of the precautionary principle applied to global change. When the protocol was adopted, there was still some scientific uncertainty about the evidence for the effect of CFCs on ozone depletion. You may recall from Chapter 14 that CFCs are chemicals that were used for refrigeration and other commercial applications. Despite the uncertainty about the effect of CFCs on the atmosphere, the protocol recommended eliminating their use. In this case, economic and political factors were balanced with the scientific findings to reach an agreement that CFCs should be phased out over a period of decades rather than immediately. Part of the success of the Montreal Protocol has been credited to the availability of an affordable and fairly effective replacement for CFCs. It has proven much more difficult to find affordable and effective replacements for the fossil fuels we currently use. Therefore, it is less likely that a similar scenario will unfold with respect to a reduction of greenhouse gases.

713

The precautionary principle is a relatively new and important part of environmental policy. It does not recommend or require any specific actions, but it does provide a reminder to environmental policy makers and managers that, in many cases, absolute scientific certainty may come too late when dealing with potentially serious environmental harms.

World Agencies

United Nations (UN) A global institution dedicated to promoting dialogue among countries with the goal of maintaining world peace.

By considering the variety of worldviews presented earlier, and to the extent a particular country or agency subscribes to the precautionary principle, we can begin to understand more about the decision-

The United Nations Environment Programme

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) A program of the United Nations responsible for gathering environmental information, conducting research, and assessing environmental problems.

The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) is a program of the United Nations responsible for gathering environmental information, conducting research, and assessing environmental problems. Headquartered in Nairobi, Kenya, UNEP is also the international agency responsible for negotiating certain environmental treaties. In particular, the Convention on Biological Diversity, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), and the Montreal Protocol on Substances That Deplete the Ozone Layer are three important international treaties UNEP negotiated. The Global Environment Outlook (GEO) reports are prepared under the auspices of UNEP.

The World Bank

World Bank A global institution that provides technical and financial assistance to developing countries with the objectives of reducing poverty and promoting growth, especially in the poorest countries.

The World Bank is a global institution that provides technical and financial assistance to developing countries with the objectives of reducing poverty and promoting growth, especially in the poorest countries. The World Bank cites four goals for economic development: (1) educating government officials and strengthening governments; (2) creating infrastructure; (3) developing financial systems, from microcredit to much larger systems; and (4) combating corruption. Critics of the World Bank maintain that there is too little consideration of environmental and ecological impacts when projects are evaluated and approved.

The World Health Organization

World Health Organization (WHO) A global institution dedicated to the improvement of human health by monitoring and assessing health trends and providing medical advice to countries.

Headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland, the World Health Organization (WHO) is a global institution dedicated to the improvement of human health by monitoring and assessing health trends and providing medical advice to countries (FIGURE 66.1). It is the group within the UN responsible for human health, including combating the spread of infectious diseases, such as those that are exacerbated by global climate changes. This organization is also responsible for health issues in crises and emergencies created by storms and other natural disasters. The five key objectives of the WHO are: (1) promoting development, which should lead to improved health of individuals; (2) fostering health security to defend against outbreaks of emerging diseases; (3) strengthening health care systems; (4) coordinating and synthesizing health research, information, and evidence; and (5) enhancing partnerships with other organizations.

714

The United Nations Development Programme

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) An international program that works in 166 countries around the world to advocate change that will help people obtain a better life through development.

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) is an international program that operates in 166 countries around the world to advocate change that will help people obtain a better life through development. Headquartered in New York City, UNDP has a primary mission of addressing and facilitating issues of democratic governance, poverty reduction, crisis prevention and recovery, environment and energy issues, and prevention of the spread of HIV/AIDS. UNDP prepares an annual Human Development Report (HDR) that is an extremely useful measurement tool for the status of the human population.

Other Agencies

There are also a great number of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) that work on worldwide environmental issues. These include Greenpeace, the International Union for Conservation of Nature, World Wide Fund for Nature (formerly World Wildlife Fund), and Friends of the Earth International.

U.S. Agencies

In January 1969, offshore oil platforms 10 kilometers (6 miles) from Santa Barbara, California, began to leak oil. Roughly 11.4 million liters (3 million gallons) of oil spilled out over the next 11 days and the leak continued throughout the year. This was not the first oil spill during the 1960s, nor the largest, but its proximity to the southern California coast resulted in something new—

The first Earth Day, April 22, 1970, was partially the result of public reaction to the Santa Barbara oil spill and to other environmental problems that surfaced during the 1960s, such as those documented by Rachel Carson in her book Silent Spring (FIGURE 66.2). Earth Day 1970 is the symbolic birthday of the modern expression of the view that the natural environment and human society are inextricably connected. It also signals the beginning of contemporary environmental policy. Before 1970, environmental policy focused primarily on biological and physical systems as economic resources for an industrial society. After 1970, sound environmental policy expanded to include the idea that economic benefits must be balanced by environmental science, environmental equity, and intergenerational equity—

715

Since the early 1970s, several important U.S. agencies have been created to monitor human impact on the environment as well as to promote environmental and human health.

The Environmental Protection Agency

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) The U.S. organization that oversees all governmental efforts related to the environment, including science, research, assessment, and education.

In 1970, President Richard Nixon signed the bill authorizing the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), which oversees all governmental efforts related to the environment including science, research, assessment, and education. Headquartered in Washington, D.C., the EPA also writes and develops regulations and works with the Department of Justice and Department of State and U.S. Native American governments to enforce those regulations.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration

Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) An agency of the U.S. Department of Labor, responsible for the enforcement of health and safety regulations.

Also in 1970, President Nixon signed the act creating the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), an agency of the U.S. Department of Labor that is responsible for the enforcement of health and safety regulations. Its main mission is to prevent injuries, illnesses, and deaths in the workplace. OSHA conducts inspections, workshops, and education efforts to achieve its goals. Limiting exposure to chemicals and pollutants in the workplace is one way that OSHA is involved in environmental protection.

The Department of Energy

Department of Energy (DOE) The U.S. organization that advances the energy and economic security of the United States.

In 1977, President Jimmy Carter signed an act creating the Department of Energy (DOE), which advances the energy and economic security of the United States. Among its top goals are scientific discovery, innovation, and environmental responsibility. Within the DOE, the Energy Information Agency gathers data on the use of energy in the United States and elsewhere.

There are several approaches to measuring and achieving sustainability

Just as there are agencies, laws, and regulations designed to initiate and enhance sustainability, there are also a number of lenses through which to view the world, and a number of measurements or indexes used to evaluate sustainability. This section introduces some of these measurements and views. Eventually, some or all of these indices may become more directly involved in the measurement and assessment of sustainability.

Measuring Human Status

Despite the variety of economic indicators that are used around the world, there is still a call for a measurement that reports on the status of human beings with the specific goal of covering some of the noneconomic parameters such as levels of health and education. A variety of these are used and we describe two of them here.

The Human Development Index

Human development index (HDI) A measurement index that combines three basic measures of human status: life expectancy; knowledge and education.

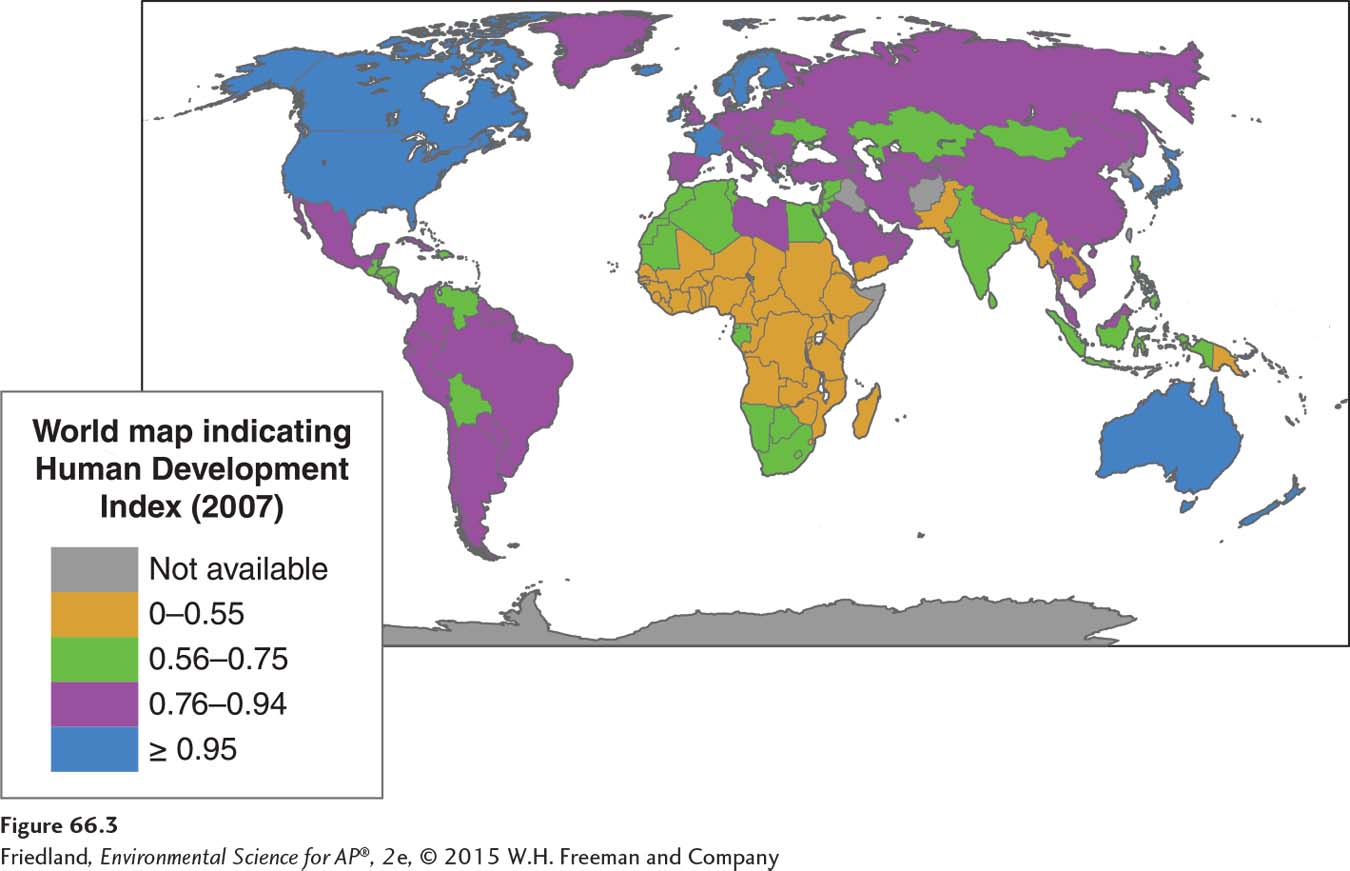

The human development index (HDI) is a measurement index that combines three basic measures of human status: life expectancy; knowledge and education, as shown in adult literacy rate and educational attainment; and standard of living, as shown in per capita GDP and individual purchasing power. HDI was developed in 1990 by economists from Pakistan, England, and the United States, and it has been used since then by the UNDP in its annual HDR. As an index, HDI serves to rank countries in order of development and determine whether they are developed, developing, or underdeveloped. FIGURE 66.3 shows the range of HDI values and the distribution among countries. As you might expect, most of the developed countries have the highest HDI values.

The Human Poverty Index

Human poverty index (HPI) A measurement index developed by the United Nations to investigate the proportion of a population suffering from deprivation in a country with a high HDI.

The human poverty index (HPI) is a measurement index developed by the United Nations to investigate the proportion of a population suffering from deprivation in a country with a high HDI. This index measures three things: longevity, as indicated by the percentage of the population not expected to live past 40; knowledge, as measured by the adult illiteracy rate; and standard of living, as indicated by the proportion of the population without access to clean water and health services, as well as the percentage of children under 5 years of age who are underweight.

716

The Policy Process in the United States

To be fair and effective, environmental policies should be based on scientific indicators that suggest a certain behavior or action will be best for the environment. When policy makers believe there is adequate understanding of the science, and there is a course of preferred action for states or individuals, they begin a process to develop a policy.

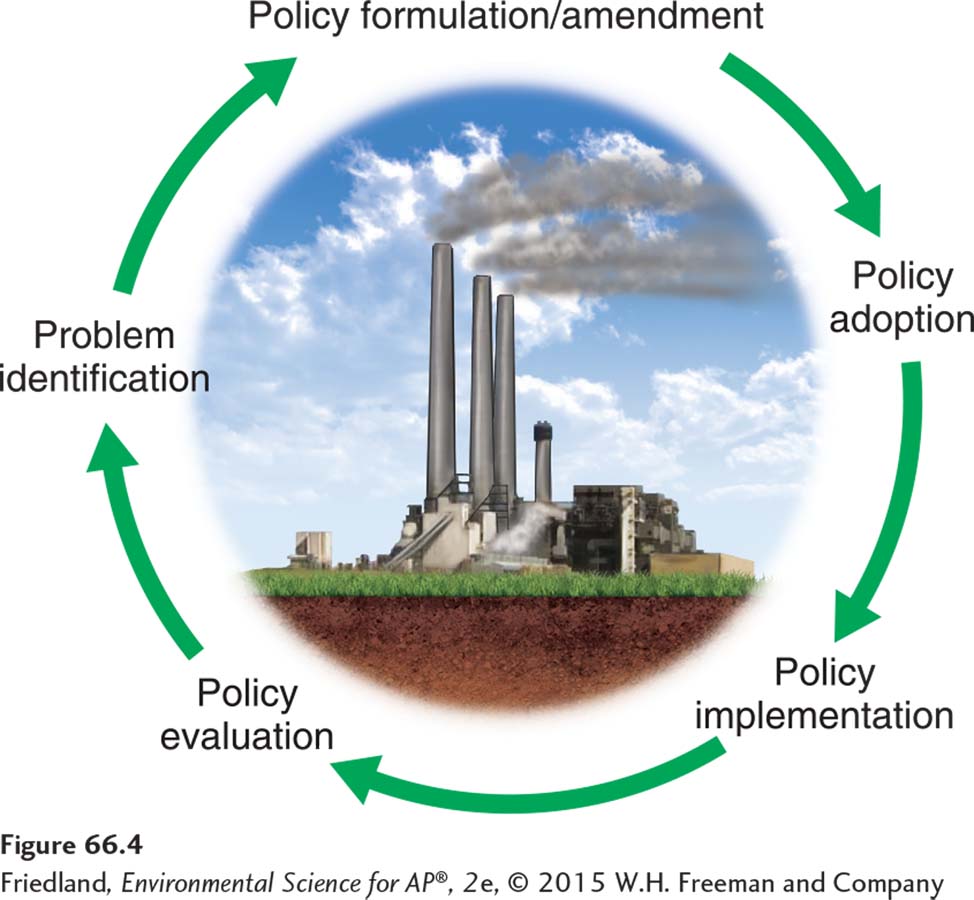

The five basic steps in a policy cycle are problem identification, policy formulation, policy adoption, policy implementation, and policy evaluation. FIGURE 66.4 depicts this process as a circular or reiterative process. As a policy is evaluated, the need for amendment might arise. When an amendment is initiated, it follows roughly the same steps. Many good environmental policies have had numerous amendments. For example, the Clean Air Act has been amended twice, and even the original Clean Air Act of 1970 was actually a modification of earlier clean air legislation.

Legislative Approaches to Encourage Sustainability

Command-

Incentive-

United States governmental agencies have tried many ways to protect the environment, promote human safety and welfare and, in some cases, internalize externalities. The command-

717

Green tax A tax placed on environmentally harmful activities or emissions in an attempt to internalize some of the externalities that may be involved in the life cycle of those activities or products.

Taxation is a major deterrent used to discourage companies from producing pollution and generating other negative impacts. A green tax is a tax placed on environmentally harmful activities or emissions in an attempt to internalize some of the externalities that may be involved in the life cycle of those activities or products. However, a tax alone may not be sufficient to achieve the desired results. Sometimes rebates or tax credits are given to individuals and businesses purchasing certain items such as energy-

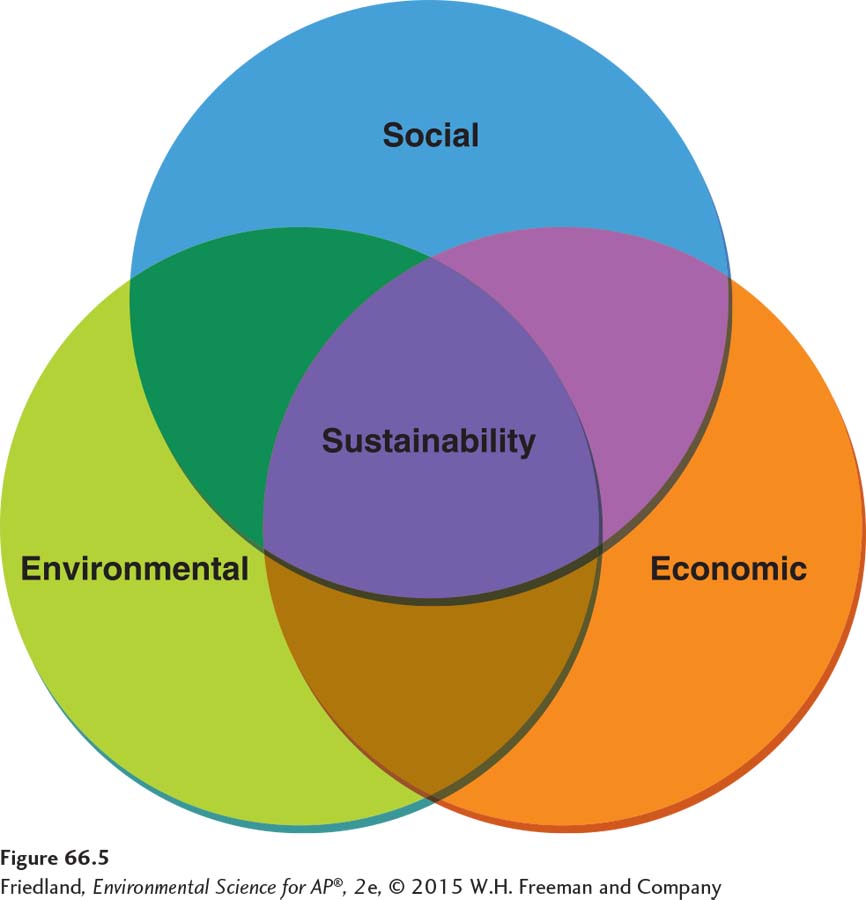

Triple bottom line An approach to sustainability that considers three factors—

In 1996, President Clinton’s Council on Sustainable Development declared that “the essence of sustainable development is the recognition that the pursuit of one set of goals affects others and that we must pursue policies that integrate economic, environmental, and social goals.” The triple bottom line is an approach to sustainability that considers three factors—

U.S. Policies for Promoting Sustainability

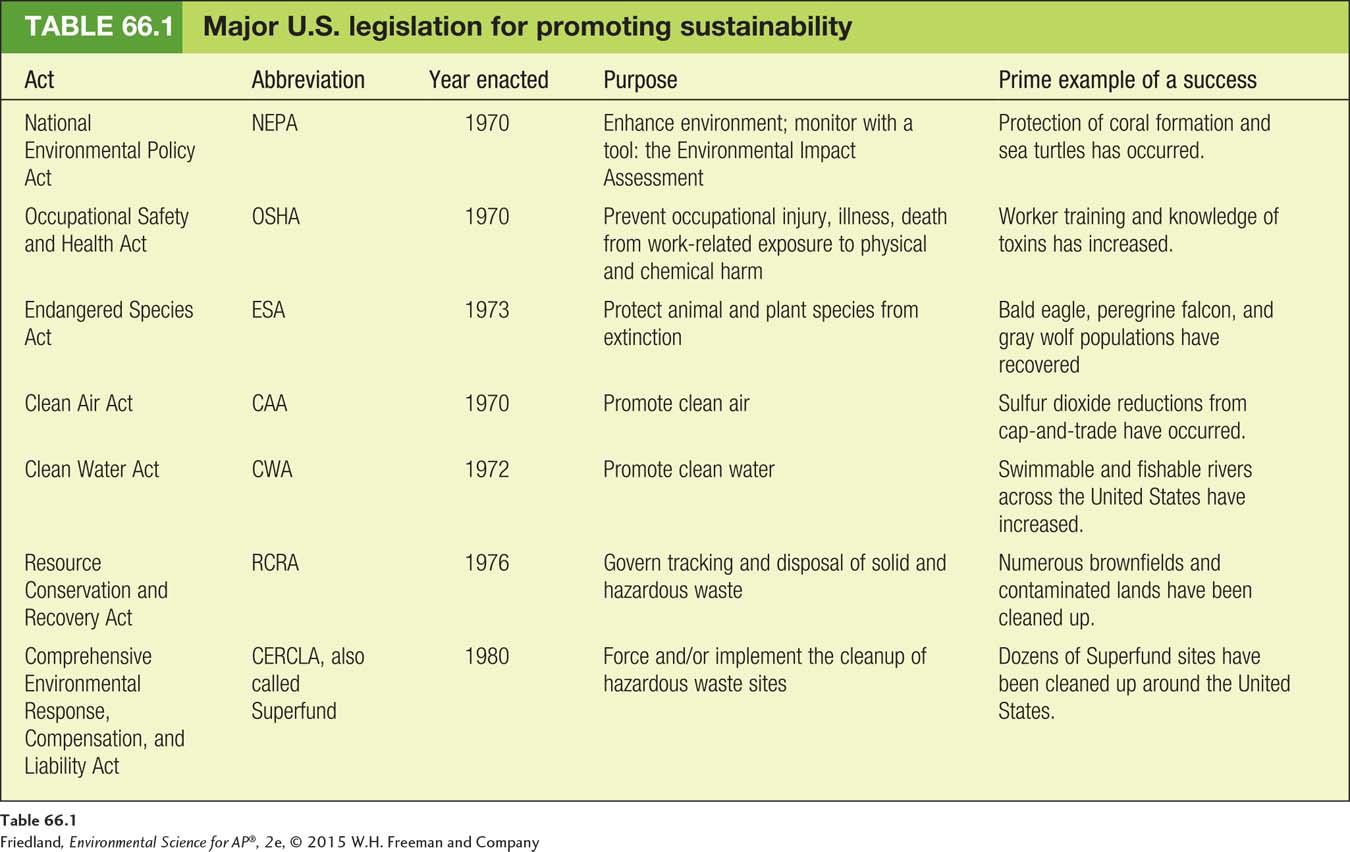

Of the many regulations that have been established in the last 50 years or so in the United States, there are at least seven important pieces of legislation that may help move the United States toward sustainability. All of these regulations have been discussed in other chapters and are summarized in TABLE 66.1.

Two major challenges of our time are reducing poverty and stewarding the environment

The classic environmental dichotomy is “jobs versus the environment.” Those primarily concerned with human well-

Poverty and Inequity

Approximately one-

718

In 2000, the United Nations offered an eight-

Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger

Achieve universal primary education

Promote gender equality and empower women

Reduce child mortality

Improve maternal health

Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases

Ensure environmental sustainability

Develop a global partnership for development

As of this writing, some countries are well on their way to meeting these goals while others lag far behind. As with environmental laws and their implementation, the distance from resolutions to results is immense, and not all developed countries have committed the resources that they had promised.

One proponent of the UN MDGs was Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Dr. Wangari Maathai (1940–

Environmental Justice

The typical North American uses many more resources than the average person in many other parts of the world. This situation is not equitable. The subject of fair distribution of the resources of Earth, known as environmental equity, has received increasing international attention in recent years. Beyond moral objections to inequity, there are concerns about sustainability. We have seen how increased resource use usually increases harm to the environment. As more and more people develop a legitimate desire for better living conditions, the resources of Earth may not be able to support continued consumption at such high levels. Closely related to the equity of resource allocation are questions of the inequitable distribution of pollution and of environmental degradation with their adverse effects on humans and ecosystems. All of these topics fall under the subject of environmental equity.

719

As we discussed in Chapter 16 and elsewhere, African Americans and other minorities in the United States are more likely than Caucasians to live in an area with solid waste incinerators, chemical production plants, and other so-

More recently, it has become clear that the subjects of disproportionate exposure to environmental hazards were not only African Americans, but all races in lower income brackets. Moreover, the problem was not limited to the United States. The concept was broadened and named environmental justice, which is both a social movement and an academic field of study. Those involved in environmental justice examine whether there is equal enforcement of environmental laws and elimination of disparities—

Individual and Community Action

There are a fair number of people who believe that whether or not governments and private agencies are able to achieve their goals, individuals can and must act to further their own goals of sustaining human existence on the planet. These individuals have begun to make attempts to live a sustainable existence without government incentives, taxes, or other measures. They have begun activities such as calculating their own ecological footprint, carbon footprint, energy footprint, and other metrics to determine how much of an impact they are making on Earth. From this starting point, they have begun to make changes in their consumption, behavior, and lifestyle to reduce that impact. Some people act on their own while others act through groups and organizations. They have adopted a philosophy represented by the saying, “If the people lead, the leaders will follow.” Some individuals have joined together to organize communities centered around philosophies of sustainability.

720

Van Jones, a graduate of Yale Law School, was a community organizer in San Francisco working on civil rights and human justice issues when he decided to combine concerns about the environment and global climate change with the need for creating jobs in cities (FIGURE 66.7). He founded an organization called Green for All and in 2008 published a book titled The Green Collar Economy: How One Solution Can Fix Our Two Biggest Problems. The two problems, as he sees it, are global warming and urban poverty. He believes that creating green jobs, such as insulating buildings, constructing wind turbines and solar collectors, and building and operating mass transit systems, will improve the living conditions of some of the poorest people in the nation and reduce our impact on the environment. For Van Jones, this is a win-

Majora Carter exemplifies another model of how to participate in community activities. She was born and raised in the South Bronx section of New York City and is a Wesleyan University and New York University graduate. She founded a not-