7.6 Journey of the Coconut

Assess the relationship between people and the coconut palm and apply that knowledge to other organisms used by people.

Many people associate the coconut (Cocos nucifera) with food or with a tropical vacation getaway. The coconut is certainly an important food, and it is an icon of tropical paradise. But it also illuminates many fascinating principles of biogeography.

Geographers are interested in where things are and why they are where they are. No one knows for certain where the coconut palm originated. Today, the tree has a pantropical distribution, meaning that it is found throughout all coastal tropical regions. But where did it first evolve? How did it come to be spread across the tropics?

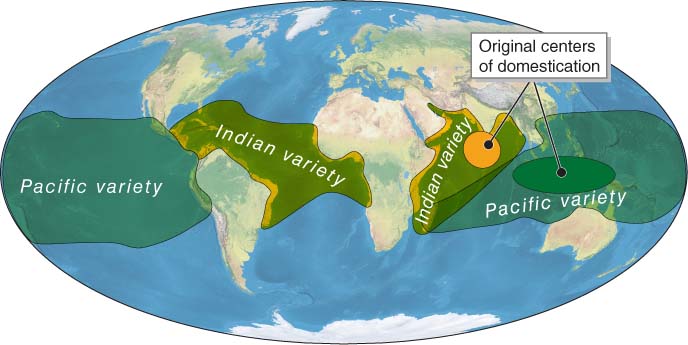

Genetic evidence suggests that the coconut palm arose some 11 million years ago in the vicinity of the Malay Peninsula, Indonesia, the Philippines, and New Guinea. Wild coconuts were domesticated by people as they began to grow it as a food source; that is, it was genetically modified by its interactions with people. Today there are two major varieties of the coconut palm, indicating that it was domesticated in two different areas: once near India, producing the Indian variety, and once near Indonesia, producing the Pacific variety (Figure 7.31).

Figure 7.31

Coconut Dispersal

Question 7.11

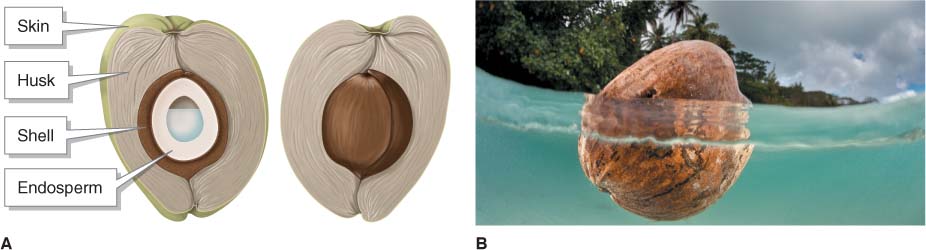

Why do coconuts float?

Coconuts float because they have evolved to disperse long distances on ocean currents.

But how did the coconut disperse across the tropical oceans from where it first arose? As we have learned in this chapter, plants disperse in a variety of ways, from being blown on the wind, to being transported in the digestive tracts of animals, to floating in water. As shown in Figure 7.32, coconuts are hydrochores and are well adapted to disperse by floating in water.

Figure 7.32

248

If a coconut seed disperses north or south of about 26 degrees latitude, it cannot successfully establish a new population because of the limiting factors of low winter temperatures and dry air. The coconut is restricted to humid tropical regions and mostly to coastal regions.

Human Migration and Coconut Dispersal

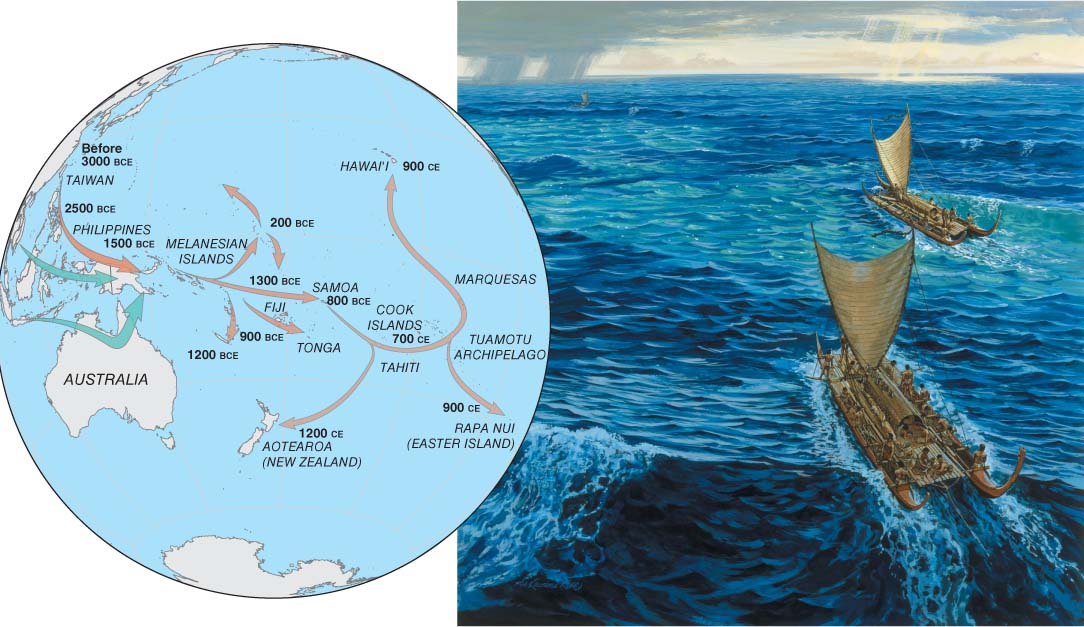

As it turns out, the same traits that allow the coconut seed to survive long-

Figure 7.33

The coconut’s stores of freshwater and nutrition made it an ideal food and source of water for ocean travelers. Archeologists know that migrating people brought the coconut with them because people and the coconut appear on remote Pacific islands at the same time. The Hawaiian Islands, for example, were colonized about 1,100 years ago. The earliest garbage dumps in Hawai‘i have coconut shells preserved in them. Before that time, there is no evidence of humans ever having set foot in Hawai‘i and that no coconut had ever grown on the islands naturally. The same is true for Easter Island (see Section GT.5).

When the first Europeans sailed to the western shores of tropical South America in the early 1500s, they found mature coconut palm groves there. Somehow, the coconut palm had dispersed to western South America. Whether Austronesian voyagers brought it there or the coconut drifted there on its own is still a mystery.

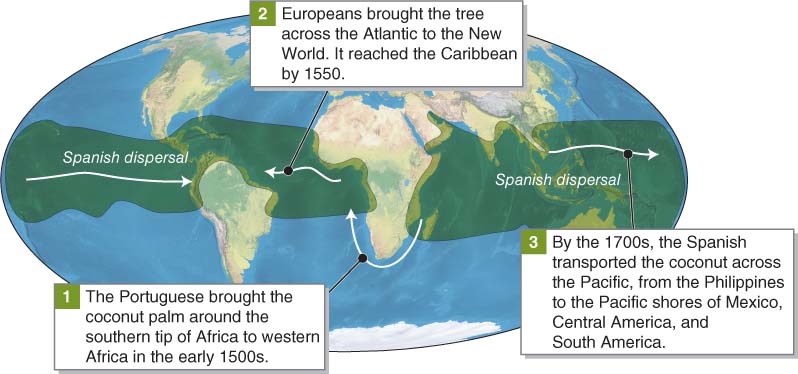

Europeans also dispersed the coconut palm across the tropics. After 1500, Europeans began dispersing coconuts to regions where the plant already grew as well as to new regions (Figure 7.34).

Figure 7.34

Artificial Selection

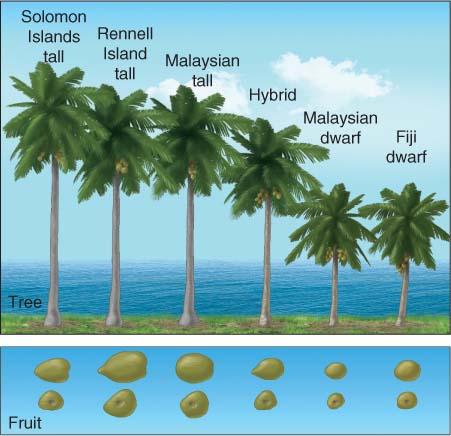

The relationship between people and the coconut illustrates not only dispersal but also the important process of artificial selection. Long ago, people began selecting individual coconut palms with useful traits, such as those with the sweetest and most nutritious meat and oil, those that did not grow too tall, and those with the best fiber. They then cultivated trees with those traits over many plant generations. Through time, this selection process created the 80 kinds of coconut palms we see today (Figure 7.35).

Figure 7.35

249

Like the coconut, most domesticated plants and animals familiar to us today are the result of artificial selection. The fruits and vegetables in the grocery store are examples of organisms changed by people. Artificial selection works through many generations as small changes add up through time. In one familiar example, all modern dog breeds, including chihuahuas and poodles, are descended from the gray wolf.

Humans and many organisms, including the coconut palm, share a relationship of mutualism. Not only do we benefit from these organisms, but they also benefit from us. The coconut’s journey reveals a fascinating story of dispersal, human migration history, plant-

250