13.4 Pressure and Heat: Metamorphic Rocks

Explain where metamorphic rocks form and how they are categorized.

Caterpillars undergo metamorphosis and become butterflies. Rocks undergo metamorphism and become new rocks. All types of rocks can undergo the process of metamorphism. Even metamorphic rocks can be metamorphosed more than once. The result of metamorphism is a physical, mineralogical, or chemical transformation of the protolith: the parent or original rock.

protolith

The parent or original rock from which metamorphic rock was formed.

The process of metamorphism involves enormous pressures, high temperatures, or both. Metamorphism occurs while the rock is in a solid state. If the rock is heated too much, it will melt into magma and form igneous rock if it cools. The thermal range for metamorphism is roughly between 100°C and 900°C (200°F and 1,600°F).

There are many variables involved in metamorphism that determine the characteristics of the final rock. These variables include the degree of heating, the degree of compression, the length of time under these conditions, the original chemical constitution of protolith, and the presence or absence of chemically reactive fluids, such as water.

Tectonic Settings of Metamorphism

Very high temperatures can be found on the crust’s surface in volcanic regions, where lava flows may cook surface rocks. High pressures and temperatures, however, are far more common deep within the crust. As a result, metamorphism is a process that normally takes place kilometers deep in the crust in regions of subduction and collision. Therefore, most metamorphic rocks are hidden away deep within the crust, and they are the least common of the three rock families on the crust’s surface. Metamorphic rocks must be exhumed if they are to be exposed.

There are two broad categories of metamorphic processes: contact metamorphism and regional metamorphism. Contact metamorphism occurs when rock comes into contact with and is heated by magma. Regional metamorphism results from the great heat and pressure found at convergent plate boundaries. Contact metamorphism is more geographically localized than regional metamorphism. Contact metamorphism and regional metamorphism do not produce different kinds of metamorphic rocks. The type of metamorphic rock that forms depends on the protolith and the degree of heating and compression.

Metamorphic Rock Categories

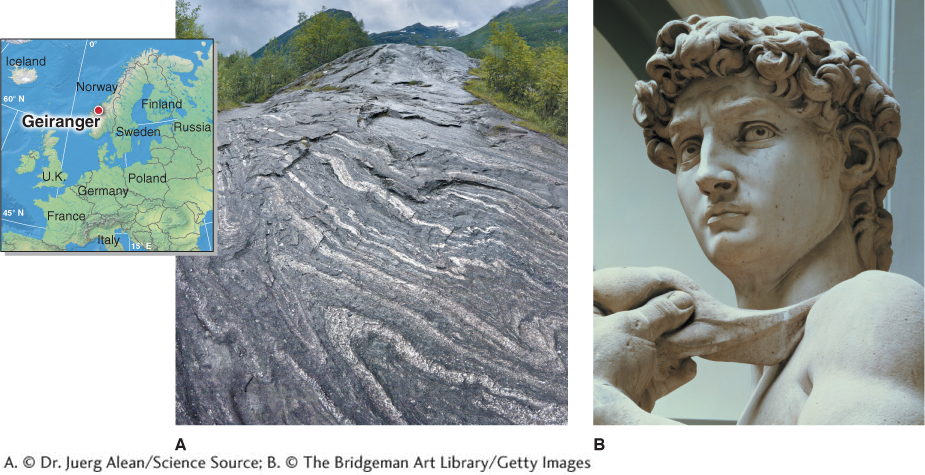

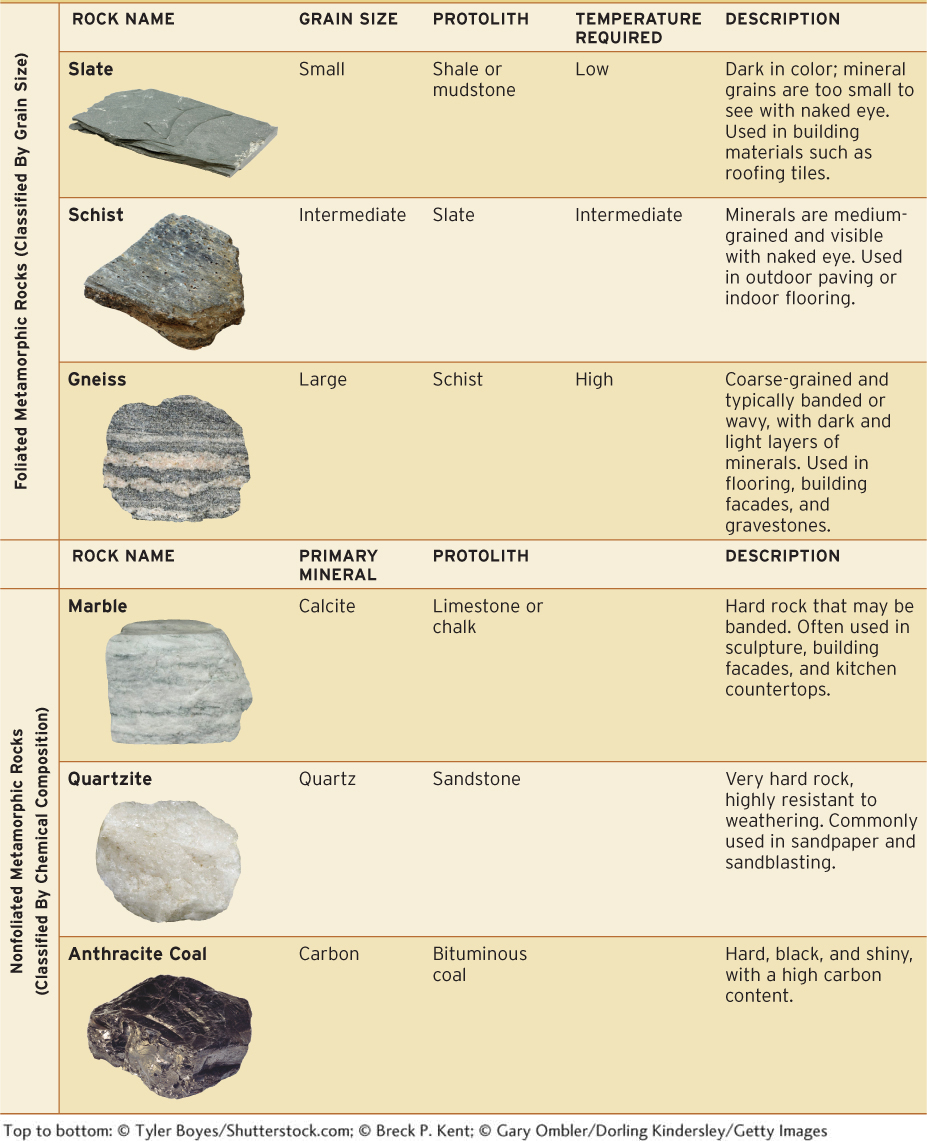

All metamorphic rocks fit into two categories on the basis of their physical structure: foliated and nonfoliated (Figure 13.17). Foliated metamorphic rocks show flat or wavy banding patterns that may superficially resemble sedimentary layers, but are unrelated to them in how they were formed. Foliation is caused by shearing forces as pressure is applied to the rock from different directions. The foliated layers are formed by mineral grains that run parallel to one another and perpendicular to the direction of compression. Nonfoliated metamorphic rocks, which form where pressure and heat are uniform, have little or no structured grain pattern or mineral arrangement and usually lack any banded or layered appearance.

Figure 13.17

433

Foliated metamorphic rocks are classified by grain size. Nonfoliated metamorphic rocks are classified by their chemical composition. The metamorphic rocks shown in Table 13.3 represent only a small fraction of the types of metamorphic rocks found in nature, but they are among the most common metamorphic rocks exposed at the crust’s surface.

434