11.1 What Does Equilibrium Mean in an Oligopoly?

422

Before we introduce the different models of oligopoly, we need to lay some groundwork. Specifically, we have to expand on our idea of what equilibrium is. The concept of equilibrium in perfect competition and in monopoly is easy. It means a price at which the quantity of the good demanded by consumers equals the quantity of the good supplied by producers. That is, the market “clears.” The market is stable at such a point: There is no excess supply or demand, and consumers and producers do not want to change their decisions.

The problem with applying that idea of equilibrium to an oligopolistic industry is that each company’s action influences what the other companies want to do. To achieve an outcome in which no firm wants to change its decision means determining more than just a price and quantity for the industry as a whole.

An equilibrium in an oligopoly starts with the same idea as in perfect competition or monopoly: The market clears. But, it adds a requirement that no company wants to change its behavior (its own price or quantity) once it knows what other companies are doing. In other words, each company must be doing as well as it can conditional on what the other companies are doing. Oligopoly equilibrium has to be stable not only in equating the total quantities supplied and demanded, but also in remaining stable among the individual producers in the market.

Nash equilibrium

An equilibrium in which each firm is doing the best it can conditional on the actions taken by its competitors.

This idea of equilibrium—

Application: An Example of Nash Equilibrium: Marketing Movies

Major computer-

Let’s suppose Disney and Warner Brothers are the only two movie companies that make animated feature films, and that their advertising influences people’s choices of what movie to see. Advertising doesn’t increase the overall number of movies people see, just which movie they watch. From Disney’s or Warner Brothers’ point of view, then, advertising can convince a moviegoer to see its movie instead of the competition’s, but advertising is not going to bring people into theaters who wouldn’t have gone otherwise.

423

Now suppose both studios plan to make the next installments in these series, The LEGO Movie 2 and Frozen 2, and release them on the same summer weekend. Further, we assume that the cost of production is still $100 million and the cost of advertising is $50 million. If both studios advertise and compete with each other, their marketing efforts will cancel out. As a result, the two will split the market, and each will bring in, let’s say, $300 million of revenue. Subtracting the $100 million production cost and the $50 million advertising cost, that leaves $150 million of profit to each studio.

If, on the other hand, the studios could somehow agree not to advertise at all, they would again split the market, but this time each would save the $50 million in advertising costs. The studio profits in this case would be greater at $200 million each.

Disney and Warner Brothers would prefer the second, higher-

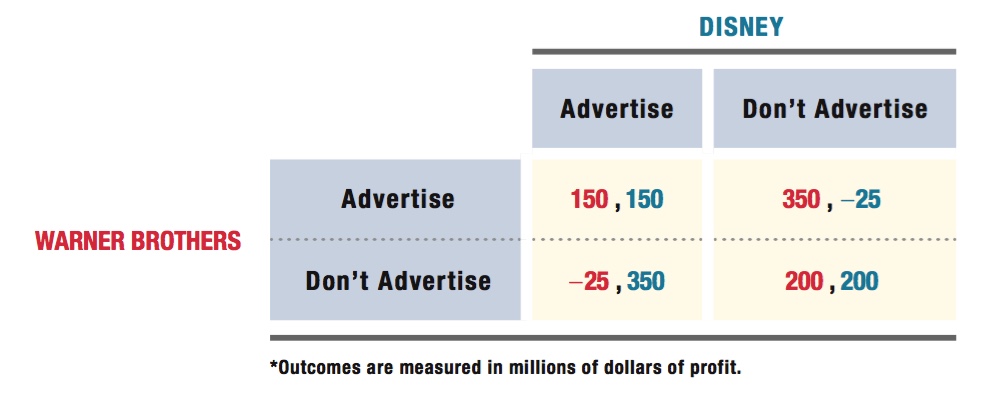

Table 11.1 lays out these scenarios. The table’s four cells correspond to the four possible profit outcomes if each firm pursues the strategy described at the top of each column and the start of each row: Both firms advertise (upper left), neither firm advertises (lower right), Warner Brothers advertises and Disney doesn’t (upper right), or vice versa (lower left). Profit is measured in millions of dollars. The number before the comma in each cell is Warner Brothers’ profit if both studios take the actions that correspond to that cell. The number after the comma is Disney’s profit.

Look at the table and think about where equilibrium might occur in this industry. At first glance, you might expect that, because they could maximize their joint profits by agreeing not to advertise, the studios should just collaborate and earn $200 million each. This is not a Nash equilibrium, however. Here’s why: Suppose a studio used this reasoning and actually held off from advertising because it believed its profit would be higher. Once the first studio decides not to advertise, however, the other studio has a strong incentive to advertise. The other studio can now earn far more profit by advertising than by going along with the don’t advertise plan. Recall that Nash equilibrium means both companies are doing the best they can, given what the other is doing. Because one studio can earn a higher profit by advertising when the other doesn’t, agreeing not to advertise is not a Nash equilibrium.

424

To make this concrete, let’s say Disney has decided not to advertise. Looking at the profits in Table 11.1, you can see that if Warner Brothers goes along, it will earn $200 million in profit. If it instead abandons the agreement and chooses to advertise, however, it will earn $350 million. Clearly, Warner Brothers will do the latter. You can also see in the table that it works the other way, too: If Warner Brothers chooses not to advertise, Disney does better by advertising (also earning $350 million instead of $200 million).

Therefore, any agreement to hold off from advertising is not stable because both parties have an incentive to cheat on it. Even if one of them sticks to the agreement, the other will earn more profit by sabotaging it. Because each studio will earn higher profit by advertising when the other does not, an outcome in which neither studio advertises cannot be a Nash equilibrium. Agreeing not to advertise is not a Nash equilibrium.

Our analysis so far has established that if one studio doesn’t advertise, the other studio wants to advertise. What is a studio’s optimal action if the other studio does advertise? The answer is in Table 11.1. If Disney advertises, Warner Brothers earns $150 million by advertising and loses $25 million by not advertising. A similar situation holds for Disney’s best response to Warner Brothers. Therefore, advertising is each studio’s best response to the other’s choice to advertise.

This means that choosing to advertise is a studio’s best course of action regardless of whether the other studio advertises or not. Because this is true for both Disney and Warner Brothers, the only Nash equilibrium in this case is for both studios to advertise. It is stable because each company is doing the best it can given what the other is doing.

prisoner’s dilemma

A situation in which the Nash equilibrium outcome is worse for all involved than another (unstable) outcome.

Notice that this is true even though it means the studios’ profits in the Nash equilibrium will be $150 million each—