11.2 Oligopoly with Identical Goods: Collusion and Cartels

Model Assumptions Collusion and Cartels

Firms make identical products.

Industry firms agree to coordinate their quantity and pricing decisions, and no firm deviates from the agreement even if breaking it is in the firm’s best self-

interest.

cartel or collusion

Oligopoly behavior in which firms coordinate and collectively act as a monopoly to gain monopoly profits.

In the next several sections, we examine several models of imperfect competition. They give very different answers about the way in which firms make decisions, so it’s important to know which model is the right one to use. A box at the start of each section lists the conditions an industry must meet for that model to apply. In the first model, all the firms in an oligopoly coordinate their production and pricing decisions to collectively act as a monopoly would. They then split the monopoly profit among themselves. This type of oligopoly behavior is known as collusion, and the organization formed when firms collude is often called a cartel.2

425

FREAKONOMICS

Apple Always Wins, or Does It?

In the months leading up to 2010, Apple was preparing for the launch of its new iPad and, with it, the introduction of the iBooks Store, which would allow users to buy and read books on mobile devices. But Apple faced a dilemma. It would be difficult for the iBooks Store to succeed unless it could match the $9.99 price point of Amazon’s Kindle, its major competitor. This price, thought by some to be less than marginal cost, had served Amazon well in building a customer base for e-

Amazon’s low price point was a concern for book publishers as well. They feared that cheap e-

As early as December 2008, the major publishers began engaging in talks and, later, meeting in private dining rooms in New York City restaurants to discuss ways to force Amazon to price above $9.99. Before one of their meetings, David Young, then chairman and CEO of Hachette Book Group, told a fellow publisher, “I hate [Amazon’s] bullying behavior and will be happy to support a strategy that restricts their plans for world domination.” The publishers started implementing their strategy. They coordinated on raising the wholesale price of e-

Knowing the publishers’ discontent with Amazon’s price point, on December 8, 2009, Eddy Cue, Apple’s senior vice president of Internet Software and Services, began requesting meetings with the major publishers to encourage them to join the iBooks Store. Cue assured the publishers that Apple would price books higher than Amazon, and after the first of his meetings he reported to Apple’s then CEO Steve Jobs that the publishers were “ecstatic” about the prospect of Apple’s entry into the industry.

Over the next several weeks, the publishers and Apple crafted a contract that featured a marketwide transition from a wholesale model to an agency model (whereby the publisher rather than the retailer sets the retail price) and a clause that guaranteed Apple would hold the lowest prices on the market. These changes would effectively drive e-

Amazon responded by also moving to an agency model in the following months. Soon thereafter, e-

Once again, it seemed as if the old Apple magic had worked: The company revolutionized yet another market by entering it. Maybe that would have been the case had things stayed the way they were in early 2012. But any cheers of victory among Apple and the publishers quickly faded when the U.S. government sued them for collusion in April 2012. The presiding judge announced her decision just over a year later: Apple was guilty. The words the judge used were scathing. “To adopt Apple’s theory, a fact-

Amazon responded by pushing prices right back down to the $9.99 price point. Its market share, which Apple had worked so hard to beat down, started to climb again. Amazon wasn’t shy about flexing its market power muscles in other ways. It understocked and refused to accept presale orders for books released by Hachette Book Group, one of the colluding publishers. Amazon was apparently making Hachette pay for its refusal to agree to a contract renewal in which most of its e-

Hachette authors like J. K. Rowling and Stephen Colbert and their fans complained loudly about Amazon’s practices and, in November 2014, Amazon and Hachette came to an agreement. Hachette books are again fully stocked. However, as Douglas Preston (founder of Authors United) noted, “If anyone thinks this is over, they are deluding themselves. Amazon covets market share the way Napoleon coveted territory.”

Is it “bad” that Amazon prices so low? In economics, the question is usually not whether something is “good” or “bad,” but rather, “Who is it good or bad for when Amazon prices so low?”

In the short run, these low prices are great for consumers, who get the same good at a much lower price. These low prices are worst for Amazon itself—

One thing we are fairly confident about: Now is a great time to buy e-

426

If the companies in an oligopoly can successfully collude, figuring out the oligopoly equilibrium is easy. The firms act collectively as a single monopolist would, and the industry equilibrium is the monopoly equilibrium (output is the level for which MR = MC and the price is determined by the demand curve, as we saw in Chapter 9).3 Don’t try this at home, though. Cartels and collusion violate the law in most every country of the world, and in the United States, it is a criminal offense that has landed many executives in prison. We discussed in Chapter 9 that governments pass and aggressively enforce antitrust laws because of monopolies’ potential to harm consumers. That doesn’t mean collusion doesn’t happen, but it explains why it’s often done in secret. This secrecy can make the instability problem we discuss next—

The Instability of Collusion and Cartels

The firms in an oligopoly would love to collude because they can earn more profit; Adam Smith, the eighteenth-

But colluding is not easy. It turns out that each member of a cartel has strong incentives not to go along. Although firms in a market might be able to come to some initial agreement over a bargaining table, collusion turns out to be very unstable.

427

Think about an industry in which there are two firms, Firm A and Firm B, that are trying to collude. To keep things simple, suppose both firms have the same constant marginal cost c. If the two firms can act collectively as a monopolist, we can follow the monopoly method from Chapter 9 to figure out the market equilibrium. We know that each firm will operate where marginal revenue equals marginal cost. The problem is that each will want to increase its output at the other’s expense.

Suppose the inverse market demand curve for their product is P = a – bQ, where P is the price per unit and Q is the quantity produced. We know from Section 9.2 that the marginal revenue curve corresponding to this linear inverse demand curve is MR = a – 2bQ. The firms will produce a quantity that sets their marginal revenue equal to their marginal cost c :

MR = MC

a – 2bQ = c

Solving this equation for Q gives Q = (a – c )/2b. This is the industry’s output when its firms collude to act like a monopolist. If we plug this back into the demand curve equation, we find the market price at this quantity: P = (a + c )/2.

This is the industry’s total production in the collusive monopoly outcome. Any combination of the individual firms’ outputs that adds to this total will result in the monopoly price and profit. Of course, the firms have to decide how to split this profit. Because both firms have the same costs, a reasonable plan would be for each firm to produce half of the output, Q/2 = (a – c)/4b, and split the monopoly profit equally. That’s what we assume here. (Later in this section, we discuss why collusion is even more unstable when firms have different costs.)

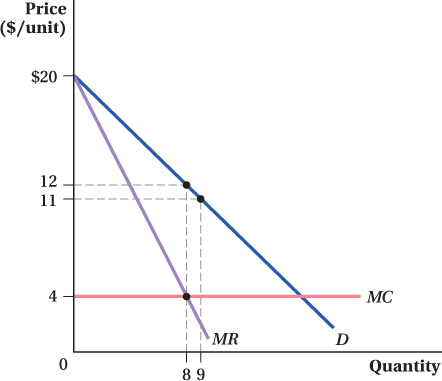

Cartel Instability: A Mathematical Analysis To see why collusion is unstable, let’s work though an example with specific numbers. Suppose the inverse demand curve is P = 20 – Q and MC = $4. Setting MR = MC, as above, the total industry output in a collusive equilibrium will be Q = 8 units, and the monopoly price will be P = $12. Assuming that Firms A and B split production evenly, each makes 4 units under collusion. This outcome is shown in Figure 11.1.

428

Collusion and cartels fall apart for the same reason that Disney and Warner Brothers can’t agree to stop advertising in our earlier example. It’s in each company’s interest to expand its output once it knows the other company is restricting output. Each company has the incentive to cheat on the collusive agreement. In other words, collusion is not a Nash equilibrium.

To see why not, think about either company’s output choice in our example. Will Firm A want to stick with the output of 4 (half the monopoly output of 8) if Firm B agrees to produce 4? If Firm A decides to increase its output to 5 instead of 4, then the total quantity produced in the industry would increase to 9. This higher output level lowers the price from $12 to $11 (the demand curve in Figure 11.1 slopes down so price falls when quantity rises).

Once Firm A cheats and increases its output, the industry is no longer at the monopoly quantity and price level, and total industry profit will fall because of overproduction. Total profit drops from Q × (P – c) = 8 × (12 – 4) = $64 at the monopoly/cartel level down to 9 × (11 – 4) = $63 after Firm A increases its output on the sly.

Although the profit of the industry as a whole falls, Firm A, the company that violates the agreement, succeeds by earning more. Its profit under collusion was $32 (half of the monopoly profits of $64). But now its profit is higher: 5 × (11 – 4) = $35. The extra sales from increasing production more than make up for the lower prices caused by the increase in production.

Remember that a Nash equilibrium requires each firm to be doing the best it can given what the other firm is doing. This example clearly shows that one firm can do better by violating the collusive agreement if the other firm continues to uphold it, so collusion is not a Nash equilibrium. In fact, the cheating firm can do better still by producing more than 5 units. If one firm sticks to the collusive agreement and makes 4 units, the profit-

Because both firms face the same incentives to cheat, collusion is extremely difficult to sustain.

Increasing the Number of Firms in the Cartel This example was for a two-

This outcome implies that the profit-

429

Besides raising the value to cheating, having more firms in a cartel also reduces the damages suffered by any firm that continues to abide by the collusive agreement. This is because the profit losses caused by the cheating will be spread across more firms. This factor further contributes to the difficulty of maintaining collusion when more firms are involved.

This cheating problem is familiar to cartels everywhere. Each firm in the cartel wants every other firm to collude, thereby raising the market price, while it steals away business from everyone else by producing more output, thus lowering the market price. Because every firm in a cartel has this same incentive to cheat, it’s difficult to persuade anyone to collude in the first place.

Application: OPEC and the Control of Oil

4See http:/

The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) is an example of a cartel that has a lot of difficulty coordinating the actions of all 12 of its members to keep the price of its good, oil, high. First of all, OPEC nations wouldn’t be monopolists even if they could coordinate their actions, because they don’t control all of the world’s supply of oil. More than half of the world’s current oil production comes from non-

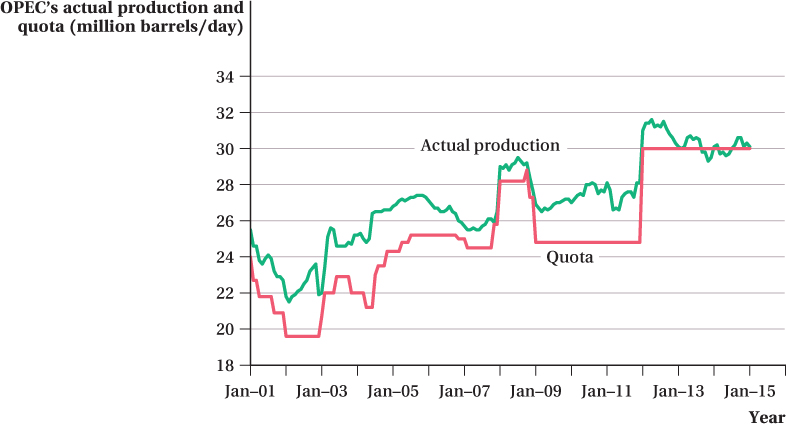

On top of that, OPEC has trouble keeping itself together because of a cartel’s natural instability. Since its founding, the cartel had met regularly to assign production quotas for each member. Frequently, however, the members chose not to abide by the agreement and overpump oil. And in this case, “frequently” meant more or less all the time. Figure 11.2 shows OPEC’s production quota agreements compared to its actual production since 2001.5 Through 2011, actual production never matched the agreed upon numbers. Member countries always pumped more, just as economics would predict. Each member has a great temptation to overproduce given the cartel setup.

In 2012 OPEC tried a new strategy for meeting its production quotas: giving up. When Iraq was brought back into the production agreement in January (it had been exempted from adhering to quotas up to that time), OPEC raised its quota by 5.2 million barrels per day, despite the fact that Iraq was only producing 2.7 million barrels per day at the time. Even that wasn’t enough, however; it took another 20 months before OPEC’s production fell below even this expanded target. It has hovered around that level since.

It kept hovering when, in late 2014, a big increase in the supply of oil from North American shale discoveries and a slowdown of demand in China caused oil prices to plunge by about 50% in just six months. All eyes turned to OPEC to see if its member countries would restrict supply and drive the price back up. OPEC could not agree to do so.

OPEC must wish it could just be a monopoly, but it ain’t gonna happen. Getting a cartel to act as a single monopolist is harder than it looks. So next time you pay $60 to fill your gas tank, go ahead and get mad! But don’t just blame this on OPEC. It doesn’t have its act together often enough to actually make your gas prices stay high.

430

See the problem worked out using calculus

See the problem worked out using calculus

figure it out 11.1

Suppose that Squeaky Clean and Biobase are the only two producers of chlorine for swimming pools. The inverse market demand for chlorine is P = 32 – 2Q, where Q is measured in tons and P is dollars per ton. Assume that chlorine can be produced by either firm at a constant marginal cost of $16 per ton and there are no fixed costs.

If the two firms collude and act like a monopoly, agreeing to evenly split the market, how much will each firm produce and what will the price of a ton of chlorine be? How much profit will each firm earn?

Does Squeaky Clean have an incentive to cheat on this agreement by producing an additional ton of chlorine? Explain.

Does Squeaky Clean’s decision to cheat affect Biobase’s profit? Explain.

Suppose that both firms agree to each produce 1 ton more than they were producing in part (a). How much profit will each firm earn? Does Squeaky Clean now have an incentive to cheat on this agreement by producing another ton of chlorine? Explain.

Solution:

If the firms agree to act like a monopoly, they will set MR = MC to solve for the profit-

maximizing output: MR = MC

32 – 4Q = 16

4Q = 16

Q = 4

and each firm will produce 2 tons. To find the price, we substitute the market quantity (Q = 4) into the inverse demand equation:

P = 32 – 2Q = 32 – 2(4) = $24 per ton

Each firm will earn a profit of ($24 – $16) × 2 = $16.

If Squeaky Clean cheats and produces 3 tons, Q rises to 5 and price falls to $22. Squeaky Clean’s profit will be equal to ($22 – $16) × 3 = $18. Therefore, Squeaky Clean does have an incentive to cheat on the agreement because its profit would rise.

431

If Squeaky Clean cheats, the price in the market falls to $22. This reduces Biobase’s profit, which is now ($22 – $16) × 2 = $12.

If both firms agree to limit production to 3 tons, Q = 6 and P = $20. Therefore, each firm earns a profit of ($20 – $16) × 3 = $12. If Squeaky Clean tries to produce 4 tons of chlorine, Q rises to 7 and P falls to $18. Therefore, Squeaky Clean’s profit will be ($18 – $16) × 4 = $8. Thus, Squeaky Clean does not have an incentive to cheat on this agreement because its profit would fall.

What Makes Collusion Easier?

Although collusion isn’t an especially stable form of oligopoly, there are some conditions that make it more likely to succeed.

The first thing an aspiring cartel needs is a way to detect and punish cheaters. We just saw that each company in a cartel has the private incentive to produce more output (or charge a lower price) than the collusive level. If the other firms in a cartel have no way of knowing when a member cheats—

Second, a cartel may find it easier to succeed if there is little variation in marginal costs across its members. To maximize profit, a monopoly (or a cartel trying to act like a monopoly) wants to use the lowest-

Third, cartels are more stable when firms take the long view and care more about the future. Think of staying in a cartel (i.e., choosing not to cheat on a collusive agreement) as trading off a short-

Application: The Indianapolis Concrete Cartel

6Kevin Corcoran, “The Big Fix,” The Indianapolis Star, (May 6, 2007): A1, A22–A23

In 2006 and 2007 the U.S. Department of Justice busted up a long-

432

The Indianapolis cartel struggled with instability issues. Despite the fact that price-

The group held regular meetings at local restaurants or hotels (paying cash for conference rooms to avoid leaving a paper trail) to try to adjust the agreement to current market conditions. Executives monitored agreements by anonymously gathering price quotes from their competitors over the phone. If a violation occurred, the cartel would issue threats, though it’s unclear exactly what was threatened and how many threats were actually carried out. If violations were widespread enough, the ringleaders would call an emergency meeting at the local Cracker Barrel restaurant.

These efforts met with mixed success. Sometimes cheating would overwhelm their effort to hold to an agreement. Firms were reluctant to give up the customers they had gained by undercutting the other cartel members. Still, the cartel was on occasion able to maintain enough discipline to inflate prices by an amount estimated to be as much as 17% above their noncollusive level.

Everything began to fall apart when the cartel tried to deal too aggressively with a noncooperative manager from a firm that was not part of the cartel. After repeated attempts to cajole the manager into joining the scheme, the cartel members started complaining about various aspects of his performance to his corporate bosses. Feeling backed into a corner, the manager went to the FBI and informed them of the cartel’s operations. By the time criminal proceedings ended a few years later, many careers had been destroyed and several of the cartel companies had been liquidated or bought out.