13.6 Imperfectly Competitive Factor Markets: Monopsony, a Monopoly in Factor Demand

528

We’ve restricted our attention so far to perfectly competitive factor markets. Individual demanders of factors—

As we have learned in earlier chapters, perfectly competitive markets are rare in the real world. In the next sections, we look at what happens when factor demanders or suppliers are not price takers. We begin by looking at cases in which buyers have market power.

monopsony power

When a buyer’s choice of how much of a product to buy affects the market price of that product.

We are already familiar from Chapter 9, Chapter 10 and Chapter 11 with how markets work when sellers have some monopoly power—

There are many examples of concentrated buyers who are likely to have some monopsony power. Pepsi and Coca-

Marginal Expenditure

To make things more concrete, let’s think about the market for oil workers in the Athabasca Oil Sands (AOS), which are located in a remote area of northern Alberta, Canada. If you live and work in this region, it’s likely you work in oil production and have limited ability to change jobs unless you leave the area. At the same time, only a few large companies account for most of the oil production and employment there.

These facts imply that employers in the AOS region have some monopsony power. Because each company accounts for a considerable share of the total market demand for labor, the more labor it hires, the higher the wage will rise. Note that just as we discussed regarding the relationship between monopoly and market power, a firm can have monopsony power without being literally the only buyer. The key is that it is not a price (wage) taker when it buys (hires).

We know from our analysis earlier in this chapter that in a competitive factor market, oil companies would hire workers until the marginal revenue product of those oil workers equaled the market wage. That wage would be set by market-

marginal expenditure (ME)

The incremental amount spent to buy one more unit of a product.

We can think about Syncrude’s decision in terms of marginal expenditure, ME, the incremental expenditure from buying one more unit of labor. Buyers with no market power—

529

This is easier to understand in an example. Suppose hiring 1,000 employees would cost Syncrude a wage of $50,000 per employee, while hiring 1,100 employees would raise the wage to $60,000 per employee (here, we’re treating the marginal unit of labor as being 100 employees). Syncrude’s total payroll for employing 1,000 workers would then be $50 million (1,000 × $50,000), while its payroll for hiring 1,100 workers would be $66 million (1,100 × $60,000). Therefore, its marginal expenditure (ME) for one incremental unit of labor (100 employees) is not just the $6 million it pays to hire 100 extra workers ($60,000 × 100) but $16 million ($66 million for 1,100 workers – $50 million for 1,000 workers). Syncrude’s extra hiring requires the company to pay an extra $10 million ($10,000 to each of its 1,000 non-

We can mathematically express marginal expenditure for a monopsonist as the price plus the amount that prices would change from increasing quantity times the quantity:

ME = P + (ΔP/ΔQ) × Q

If this looks familiar, it is because it’s very much like the definition of marginal revenue from Chapter 9. The difference is that for monopoly power and marginal revenue, ΔP/ΔQ is negative because it depends on the downward-

When Syncrude hires labor as a monopsonist, it faces an upward-

Factor Demand with Monopsony Power

We saw earlier in the chapter that price-

530

While the competitive and monopsony cases have the same MRP = ME rule for input demand, ME is different for a monopsonist than for a price-

Equilibrium for a Monopsony

531

To find the equilibrium of a market when a buyer has monopsony power, we follow the same three-

Derive the ME curve from the supply curve facing the buyer.

Find the quantity at which ME equals the marginal revenue product to determine the optimal quantity.

Jump down to the supply curve at that quantity to determine the price paid for the factor.

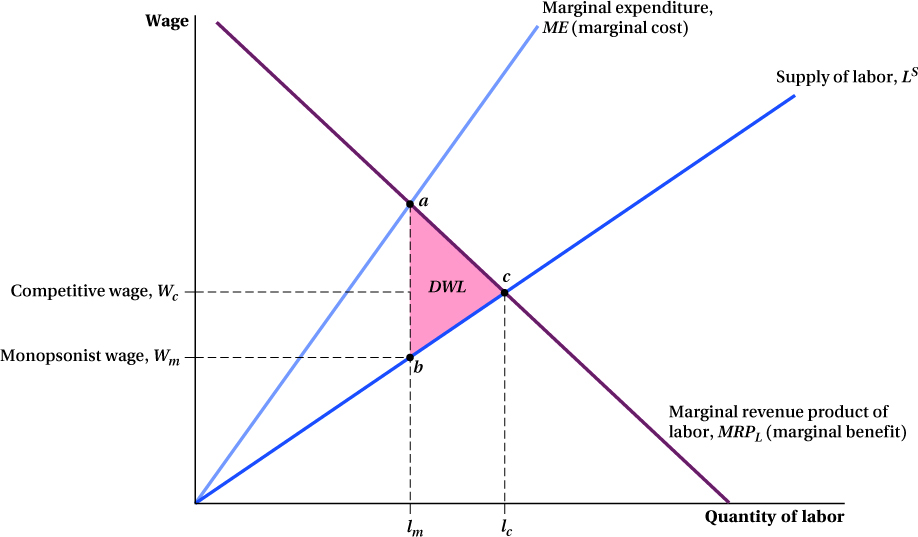

Figure 13.11 shows this analysis for Syncrude. Syncrude’s marginal revenue product curve for labor is MRPL, and the labor supply curve it faces is S. We first plot the marginal expenditure curve, ME, that corresponds to the supply curve. It is, as we know, above S, and because S is linear, it is twice as steep. Second, we find the optimal quantity of labor for Syncrude to hire by identifying where the ME curve intersects MRPL. This intersection is at point a in the figure and the quantity is lm. Third, we find the wage Syncrude pays by reading off the level of the supply curve at quantity lm. This is point b, and the corresponding wage Wm is what Syncrude has to pay workers to make them willing to supply Syncrude with its desired quantity of labor lm.

The monopsony quantity lm and wage Wm are different than those that would be found if Syncrude’s labor demand (embodied in MRPL) was instead the demand of a set of perfectly competitive buyers. In that case, the equilibrium wage and quantity of labor would be identified by point c, the intersection of the market demand and supply curves—

Just as with monopoly power, monopsony creates a deadweight loss, DWL. This arises because there will be some workers who would work for wages less than the marginal revenue product they create for the firm, but they aren’t hired because it would raise overall wages too much. In the Syncrude case shown in Figure 13.11, the units of labor that have social value but are not sold are those between lm and lc. The total size of the deadweight loss from this unsold labor is the total surplus they would have created had they been sold. Any given unit of labor has a surplus equal to the vertical distance between the labor demand curve (the value of the labor to Syncrude) and the labor supply curve (which shows what workers must be paid to be willing to work). If we add up the surplus of all the labor that is unsold in the monopsony market but would be sold in the competitive market, this is the triangular area labeled DWL in the figure. This triangle is the deadweight loss of monopsony power.

Application: The Rookie Pay Schedule in the NBA

One fairly prominent example of monopsony power at work in the labor market is the market for young players in the National Basketball Association. The NBA is a monopsony because it is the only buyer of professional basketball services in the United States, and its teams coordinate their hiring to sustain this single-

Great players like Chris Paul, LeBron James, and Stephen Curry, for example, were not allowed to make more than the maximum salary specified in a rookie contract during their early years in the league, even though their true value was much higher. Analysts at 82games.com, for example, estimated that in LeBron James’s third season, his fair salary in a competitive market would have been $27.4 million. Instead, his contract only allowed him to be paid $4.6 million. While that’s not pocket change, it’s a whole lot less than he was worth, and what he would have been paid if the NBA didn’t coordinate the rookie hiring decisions of its teams.

532

figure it out 13.2

Richland Uranium Mining operates a mine in a remote area. Because of its location, it has monopsony power in the labor market. Its marginal revenue product of labor curve is MRPl = 800 – 10l, where l is the total number of miners it hires and MRPl is measured in thousands of dollars per miner. The labor supply curve of local miners is W = 10l – 100, where W is the wage.

What is Richland’s marginal expenditure curve for labor?

What quantity of labor does it want to hire, and what wage will it pay?

What would the quantity of labor and wage be if Richland’s marginal revenue product curve belonged to a perfectly competitive set of mines?

Solution:

Because the labor supply curve is linear, we know the marginal expenditure curve has twice the slope of the labor supply curve:

ME = 20l – 100

Richland will want to hire the quantity of labor that equates its marginal revenue product of labor with its marginal expenditure:

MRPl = ME

800 – 10l = 20l – 100

30l = 900

lm = 30

Richland’s optimal amount of labor to hire is 30 miners.

To find the wage it must pay, we substitute the quantity of labor into the labor supply curve:

Wm = 10lm – 100

W = 10(30) – 100 = 300 – 100

Wm = 200

Richland must pay a wage of $200,000 per miner to hire 30 miners.

A competitive market would hire labor until MRPl equaled the wage from the labor supply curve. The competitive quantity of labor would therefore be

MRPl = W

800 – 10l = 10l – 100

20l = 900

lc = 45

A competitive set of mines would hire 45 miners.

The wage can be found using the supply curve:

Wc = 10lc – 100

W = 10(45) – 100 = 450 – 100

Wc = 350

The wage in a competitive market would be $350,000 per miner.