Communicate Information through Writing

As you’ve likely seen for yourself, almost every college course includes some type of writing assignment, from essay questions and research papers to creative writing and lab reports. Why do instructors assign so much writing? It’s not to torture you — remember, they have to read all the papers they assign! Rather, writing assignments help instructors answer two important questions: (1) Do my students understand the key concepts we’re covering in class? and (2) Can they think critically about the material? You use all aspects of critical thinking — gathering, evaluating, and applying information, as well as reviewing outcomes — when you write in college. The strategies in this section can help you apply those skills to your writing assignments.

Prepare to Write

Preparing effectively for your writing assignment will help you stay on track later when you write the first draft and make revisions. As you read this section on preparation, think back to Destiny’s experience. If you had fourteen days to write a paper on dictatorships, how would you prepare?

FOR DISCUSSION: Ask students what their process for writing papers has been up to this point. Discuss together how they can use the information from this chapter to make their current approach more effective or change their approach altogether.

234

Clarify Your Purpose. When you understand why you’re writing — your purpose — you can more easily organize the information and ideas in your written piece and focus on the points you want to convey. Consider these different purposes for writing:

To inform. One reason for writing is to inform the reader about a particular topic. Most of your papers in college will serve this purpose, including research reports, annotated bibliographies, review papers, and lab reports.

To persuade. In persuasive writing, you might start by conveying information about a topic and then seek to persuade your reader to view the topic in a particular way. Editorial assignments in a journalism class, policy papers in a government course, or advertising plans in a marketing course fit into this category.

To express or entertain. In expressive writing or writing for entertainment, you convey your thoughts and ideas or tell stories to enlighten an audience. Examples include writing poems or short stories for a literature course, plays for a theater course, and song lyrics for a music course.

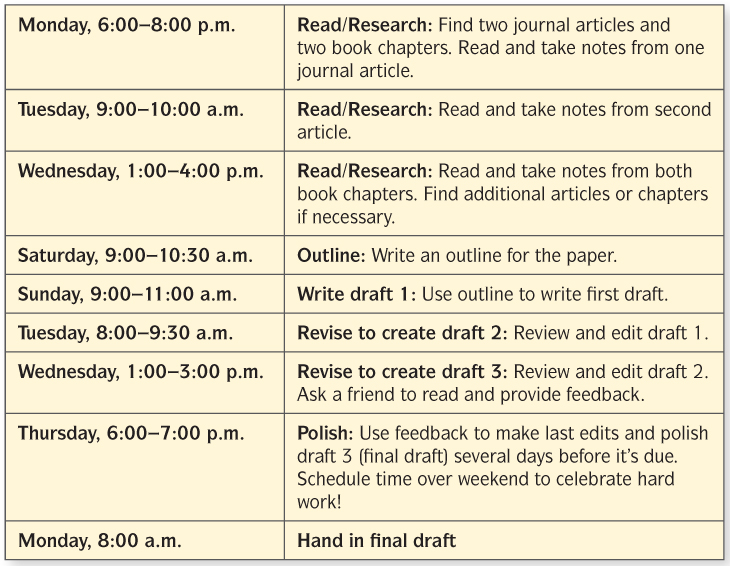

Make a Plan. Writing assignments often take longer than you expect, so schedule plenty of time to complete them. Plan out each part of the process: preparing, writing your first draft, revising, and polishing. As an example, see Figure 10.2, which is a schedule for a short research paper (about two to five pages). Not only does it build in time to write the first draft, but it also includes seven and a half hours of preparation (reading, researching, and outlining) and then four and a half hours of revising and polishing. While not everyone spends the same amounts of time on each part of the process, significant chunks of time are usually required for each step. Building a plan helps you manage and get the most from that time.

235

Choose a Topic. For some writing assignments, your instructor will give you a topic. For others, you can choose a topic. If you can choose your own topic and need inspiration, think about what you’ve found interesting in class, ask your instructor for ideas from previous terms, or talk with your classmates about how they chose a topic. You can also explore different ideas for paper topics by rereading your textbook and looking for the articles and books it cites, or by reviewing suggested readings listed in your course syllabus. Picking an interesting topic will help you stay motivated during the writing process.

FOR DISCUSSION: Ask students if they find it easier to write a paper when the instructor provides a topic or when they can choose the topic themselves. Have them explain their answers.

Conduct Research. Researching your topic gives you a chance to put your information literacy skills to work by finding information and evaluating it. You can conduct research for all types of projects, although informative writing often requires more research than persuasive, expressive, or entertaining writing.

When you’re researching, tap into the wide range of sources described earlier in this chapter, and use your critical thinking skills. Remember to evaluate what you’re reading by asking yourself:

Does the author’s argument make sense?

Is it credible?

Are there alternative arguments worth considering?

When you evaluate information you’ve found through research, you point out problems with an argument or provide alternative arguments. Then, when you write your paper, you can include your questions and evaluation in the draft.

236

For example, let’s say you’re writing a short paper on drowning deaths for a public health class. You’ve found an article whose author claims that eating ice cream causes drowning. The author backs up this claim with numbers showing that ice-cream consumption and drowning rates increase together. If you neglected to use your critical thinking skills, you might say, “Makes sense — people eat ice cream, get cramps, and drown.” But if you had your critical thinking hat on, you would be open to alternative explanations, such as this one: Both swimming (and hence drowning) and eating ice cream increase during the warmer summer months. So, although it may appear that one event causes the other, something else — the warm weather — is actually causing both events to increase. The point? Don’t unthinkingly accept the viewpoints you come across in your research. Rather, think critically before you take what you read as fact.

ACTIVITY: Present to the class five headlines from a reputable newspaper or journal and five from an online satire site such as The Onion. See if students can guess which are from the reputable source and which are satire.

ACTIVITY: Ask each student to create an outline of the writing steps described in the chapter. Have students print two copies of their outline and trade with another student. Were their outlines similar? Did they differ in any way? Invite students to refer to these outlines when they need to write a paper.

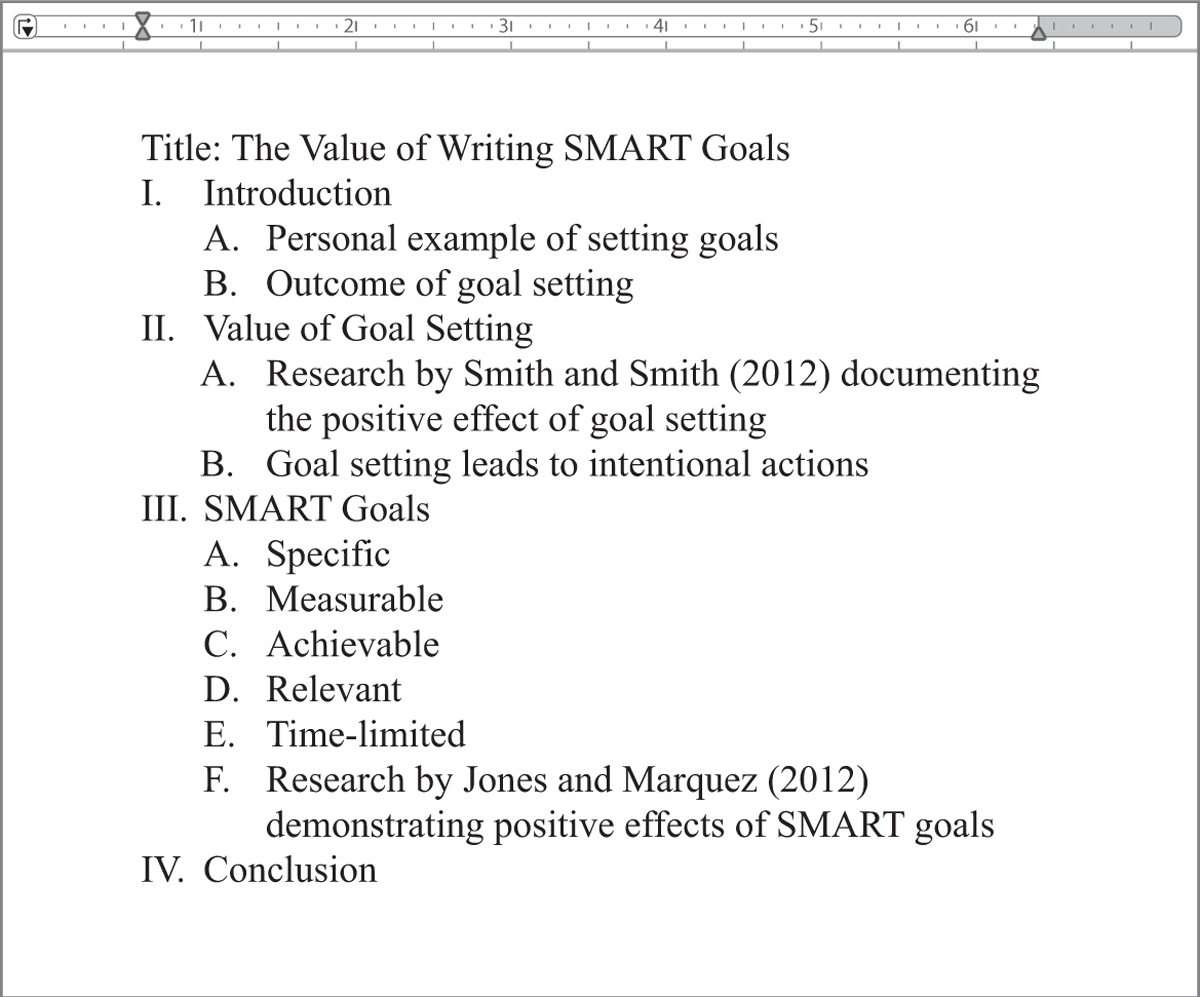

Create an Outline. An outline helps you organize your ideas before you start writing. You can use it to sketch out the structure of your entire paper and ensure that you have all the required components of the assignment, such as an introduction, citations (if required), main and supporting ideas, and a conclusion. The sample outline in Figure 10.3 has two levels of headings, but you can add as many headings and as much detail as you want. You can also include examples or quotations that you plan to use in your paper — or you can keep it simple and leave such details for the writing step. For more on the benefits of outlining, see the Spotlight on Research.

ACTIVITY: Depending on the technical savvy of your class, it may be beneficial to review features in Microsoft Word that are helpful when creating an outline. Not all students will be aware of these features.

237

CREATE AN OUTLINE TO IMPROVE YOUR WRITING

spotlight onresearch

Can creating an outline improve the quality of your written work? According to an experiment conducted by researcher Ronald Kellogg, the answer is “yes!” In his study, college students read arguments for and against outfitting city buses with equipment to serve individuals with disabilities. Then they wrote a paper in which they expressed support for the idea. Some students were instructed to create an outline first, while others were told to just start writing. Researchers then examined the length of the paper, the time spent writing, the writing speed, and the writing quality.

| Outline | No outline | |

|---|---|---|

| Length of paper | + (longer) |

– (shorter) |

| Writing time | + (more) |

– (less) |

| Writing speed | + (faster) |

– (slower) |

| Overall quality | + (higher) |

– (lower) |

What did they discover? Students who created an outline before writing

Wrote longer papers than those who didn’t create an outline (an average of 139 more words).

Spent more time writing (about seven minutes longer).

Wrote faster (11.3 compared to 8.5 words per minute).

Produced papers that were rated as higher quality by two judges.

THE BOTTOM LINE

Creating an outline can result in greater productivity during the writing process and a higher-quality paper — and, therefore, improved performance in college.

REFLECTION QUESTIONS

Question 10.1

1. How often do you create an outline before writing a paper or other assignment?

Question 10.2

2. If you’ve never created an outline, will you do so in the future? Why or why not?

Question 10.3

3. After reading about this study, what would you tell a friend about the value of outlining?

R. T. Kellogg, “Attentional Overload and Writing Performance: Effects of Rough Draft and Outline Strategies,” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 14 (1988): 355–65.

238

Write Your First Draft

Once you’ve taken time to prepare, you’re ready to write your first draft. For some students, all the preparation makes this part easy. For others, writing a draft can be intimidating or overwhelming. If you find it challenging to get started, think of writing like rolling a boulder down a hill: The hardest part is the first push to get the massive object moving. Once you put those first few words on paper, the rest of the process comes more easily. As you sit down to write, use the techniques in this section to craft a strong draft.

Develop a Thesis Statement. A thesis statement is the main idea or argument you want to convey, and it sets the stage for your entire paper. You can create your thesis at various points in the writing process. You might draft it during your research to organize your thoughts, and include it in your outline to provide clarity to that document. Or you might choose to write a thesis statement once your research and outline are done.

Thesis: The main idea or argument of a paper or an essay.

How you word your thesis depends on your writing purpose. For example, if you write a thesis statement about SMART goals, it might vary according to purpose.

To inform: Learn how to set and achieve your goals using SMART criteria.

To persuade: You should try SMART goals to improve your note-taking skills.

To express: This is how I used a SMART goal to improve my note-taking skills and succeed in college.

Craft an Engaging Introduction. Grab your reader’s attention right from the start by creating a compelling introduction to your paper. Imagine, for example, that you’re writing an essay on hunger. A perfectly serviceable — but dull — introductory sentence might read: “Hunger is a serious problem in the United States.” Compare that statement with this one: “One out of the next six people you meet will go to bed hungry tonight.” Wouldn’t that second sentence make you want to keep reading much more than the first?

ACTIVITY: Write a few topics on the board — for example, the history of farming, the impact of video games on culture, or wise stock market investment. Ask students to write their own engaging introductions to these topics as if they were going to write a paper on each subject.

Think Critically. You’ll have the opportunity to demonstrate your critical thinking skills many times as you write your draft. Here are just a few examples of how you can incorporate critical thinking into the writing process.

Provide evidence. Incorporate citations and ideas from your sources into your draft. A paper on poverty that simply says “poverty is bad” shows you haven’t really thought about your topic. But if you include statistics on the number of children in poverty who go to school hungry each day, you’ll demonstrate that you found and applied evidence. Just be sure to credit others when you use their ideas to support your point.

Interpret information and draw conclusions. As you write, interpret and draw conclusions from the information you’re working with, and incorporate these into your paper. For instance, suppose that a key source for your paper is an article about how national economies have become increasingly interconnected. You could think up three of your own examples showing the impact of globalization and work these into your draft. Then, at the end of the paper, you could identify what you see as the positive or negative effects of globalization.

Compare and contrast. If appropriate for the writing assignment, describe similarities and differences between topics. For instance, for a political science class, you might compare and contrast the reasons the United States entered the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Generate new ideas. For some writing, you’ll have an opportunity to generate original ideas — for example, in forms such as poetry, essays, or short stories in an English class, or by brainstorming new ways to use an existing product or tool in a design or engineering class.

CONNECT

TO MY CLASSES

You’ll use your critical thinking skills in every writing assignment in college. Select an upcoming assignment in this or another class, and write three or four sentences describing how you’ll demonstrate critical thinking as you complete that assignment.

239

Structure Your Paragraphs Carefully. When you’re writing, pay attention to how you structure each paragraph. The most common approach is to start with the main idea and then follow it with supporting ideas, examples, facts, or details. Focus on only one main idea in each paragraph; start a new paragraph as soon as you begin writing about another main idea.

Add a Conclusion. End your draft with a conclusion that pulls your thoughts together. A strong conclusion restates your thesis, revisits the major findings or recommendations of your paper, or summarizes your argument. To come full circle, you might even connect the concluding paragraph to the catchy introduction you created at the start of your paper.

Revise and Polish Your Paper

Once you’ve written a first draft of your paper, it’s time to revise and polish it. Consider these ideas for editing and finalizing your work.

Include transitions. Transitions connect your paragraphs and smooth the flow of ideas throughout your entire work. (For instance, the first sentence under the heading “Revise and Polish Your Paper” serves as a transition from the preceding section.) If your paper sounds choppy, adding transitions between paragraphs can help.

Use a formatting and style guide. The MLA (Modern Language Association) and APA (American Psychological Association) have established guidelines for formatting papers and citing sources. These style guides will help you with some of the “nuts and bolts” of writing a paper — such as the format to use for the title page, line spacing, margins, paragraph indents, headings, page numbers, and citation style. Including citations is especially important for avoiding plagiarism, which occurs when you use someone else’s work and call it your own (more on this later in the chapter). Ask your instructor or check your syllabus to determine which style guide you should use.

Read your paper out loud. You can identify language that sounds awkward and then revise as needed to make your writing more fluid.

Have someone else read your paper. Ask a friend or classmate to give you honest feedback. Someday you can return the favor.

Use campus resources. Use any resources your school offers to help with writing. Make an appointment at the writing center, work with a tutor, or ask your instructor to review a draft of your writing.

Polish and proofread. Once you’ve revised your draft several times to address macro-level issues of structure, flow, and clarity, give your written piece a final polish. Then step away from your paper and take a break, returning with fresh eyes to revisit and proofread it carefully. Fix any spelling, grammar, and punctuation errors, and make sure it reads just as you want it to.

241

CONNECT

TO MY RESOURCES

Your campus probably has a wide variety of resources that can help you improve your writing. Find and write down the name, location, and hours of a writing resource at your campus.

Write in Online Classes

You can use the strategies we’ve just explored to write papers in both face-to-face and online classes. However, some additional techniques can be especially helpful for writing online. Online classes are more likely to include writing assignments such as blog posts or written comments on other students’ posts. Your posts and comments will be graded, so you want to make sure they’re high quality. To do so, try these tips.

Write in complete sentences. Shorthand and slang are fine for Facebook and Twitter, but use more formal and thoughtful language when writing for your online classes.

Writing posts in online classes can feel conversational — there is a back-and-forth exchange of information — but remember that in online conversations you don’t have nonverbal cues and tone to provide context, so the tone you had in mind doesn’t always come through. As you type posts for online classes, read them out loud and listen to how they sound. Could readers interpret your tone in a more negative way than you intended? If so, rephrase your comments so that they’re more positive and constructive.

Pay attention to your emotions and how quickly you respond in these classes. If you’re having a heated discussion on a controversial topic, consider writing out your post on a piece of paper and coming back to it twenty minutes later to make sure it conveys your message appropriately.

FOR DISCUSSION: Ask students to share a time when someone interpreted their writing differently than they had intended, whether in an e-mail, a text, or a class assignment. You may also wish to share an experience you’ve had. As a class, discuss what can be done to avoid this kind of miscommunication.

240

voices of experience: student

GETTING FEEDBACK ON YOUR WRITING

| NAME: | Ashley J. Willey |

| SCHOOLS: | Highland Community College; University of Nebraska |

| MAJOR: | Advertising and Public Relations |

| CAREER GOAL: | Copy Writing |

“I enjoy being critiqued by as many people as possible, and I find it helpful to gain multiple perspectives.”

I’ve learned that the best way to become a good writer is to read good books. These books inspire me to try to emulate as many styles as possible until my own style shines through. I find myself playing around with different narration styles that I would typically never have used. I’m also blessed to have had a very good English professor, who taught me how to appreciate the knowledge I’ve gained and encouraged me to use methods of revision that have been amazing learning tools for me.

One of the best things I’ve done as a writer is to attend creative writing workshops. I enjoy being critiqued by as many people as possible, and I find it helpful to gain multiple perspectives. It’s important to go to your professors for their opinion, and not only to other students. Your professors are professionals who can provide you with the most experienced, educated opinion. I follow their advice to the best of my ability, until I get feedback that my work is creating the impression that I was aiming for. This allows me to learn from my mistakes and perfect my craft.

I’m comfortable building professional relationships with my professors and going to them after hours for advice. I’m not ashamed to ask for help, because I know that my professors are there for me. Many students fail to take advantage of the many resources available in the college setting because they’re closed off and are so focused on their goals that they miss out on opportunities. I’m getting my degree not for me but, ultimately, for my daughter. In order to go to college, I first had to obtain my GED without the help of my daughter’s father, who was not supportive of my obtaining my education. I began community college as a single mother and am now attending the University of Nebraska. I want to set the bar as high as I possibly can for my daughter.

YOUR TURN: Have you used any of the approaches that Ashley describes for improving your writing? If so, which ones? How useful have these approaches been? Have you found any other approaches helpful?