Read Different Types of Materials

The tips you’ve learned so far in this chapter can help you with any reading assignment in college. However, there are also more specific tips you can use for particular types of reading materials, such as math and science books, original research articles, and readings for online courses. Give these a try.

CONNECT

TO MY CLASSES

Have you been doing a lot of reading in your other classes this term? Think about how the ideas in this chapter might help you with that reading. Write down two strategies you can apply immediately to the reading assignments for your other classes.

Read for Math and Science Classes

Math and science courses aren’t identical — for example, chemistry isn’t the same as calculus. That said, these courses share enough in common that you can use similar strategies for both science and math reading assignments.

Budget your time wisely. Math and science reading tends to be dense, so schedule enough time to complete it by the due date.

Keep up with your work. Many math and science classes are linear: To solve problems in week 2, you have to use what you learned in week 1, and so on. As you read, if you encounter a topic you don’t understand, spend enough time on it to grasp it. If you’re still struggling with it, get help before your instructor moves too far ahead.

Follow the rules. Math and science have rules that must be followed, so be sure you understand each step of the formula or theorem you’re reading about. If you miss a step or break a rule when trying to solve an equation or prove a theorem, you’ll be more likely to come up with incorrect answers.

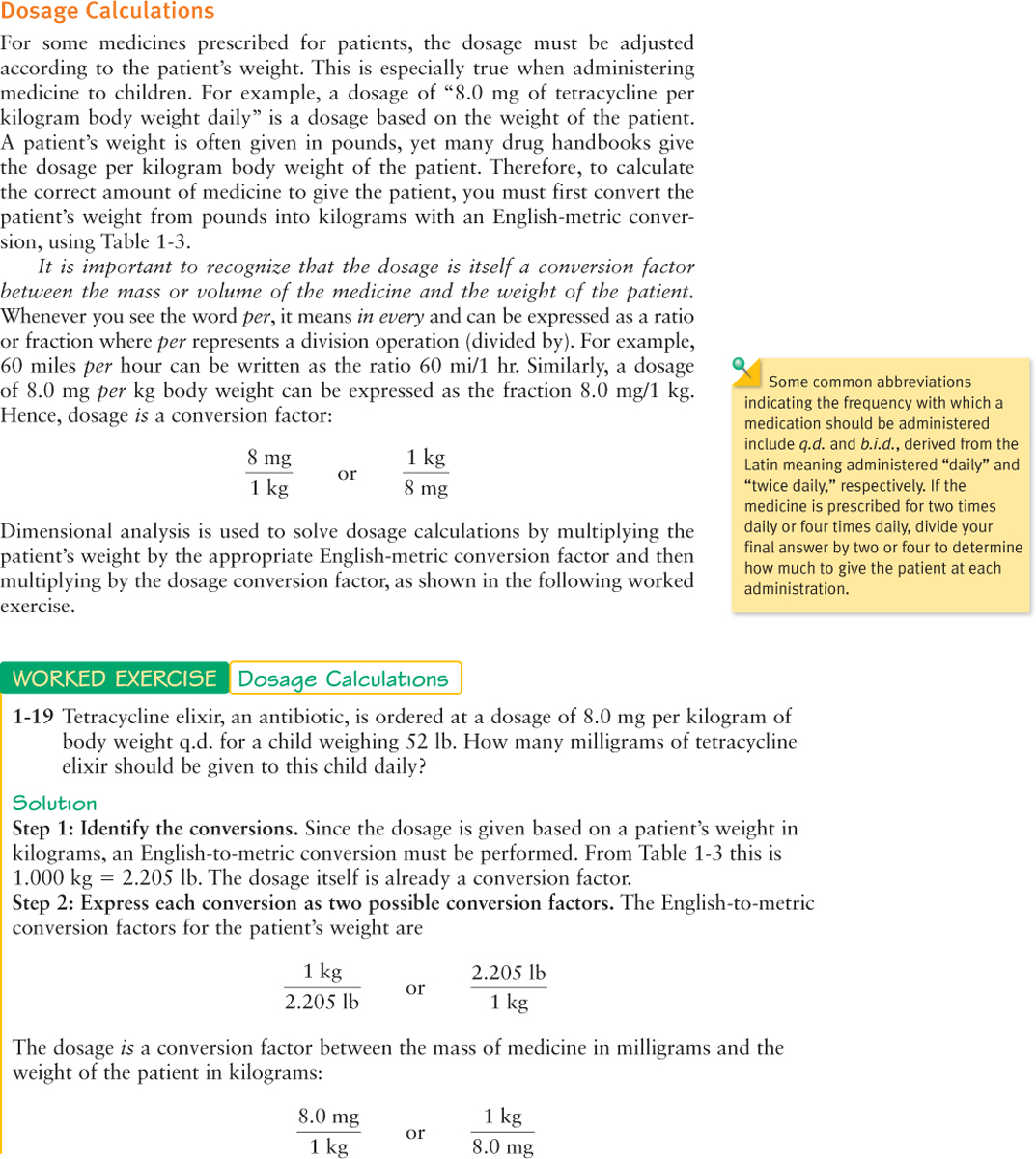

Understand symbols and formulas. If you feel as though you’re learning a new language in your math and science classes, that’s because in some ways you are. In mathematics and in sciences such as chemistry, engineering, and physics, key information is often expressed in symbols and formulas rather than in words (see Figure 6.5). To understand the material in these classes, pay special attention to these elements — don’t skip over them as you read.

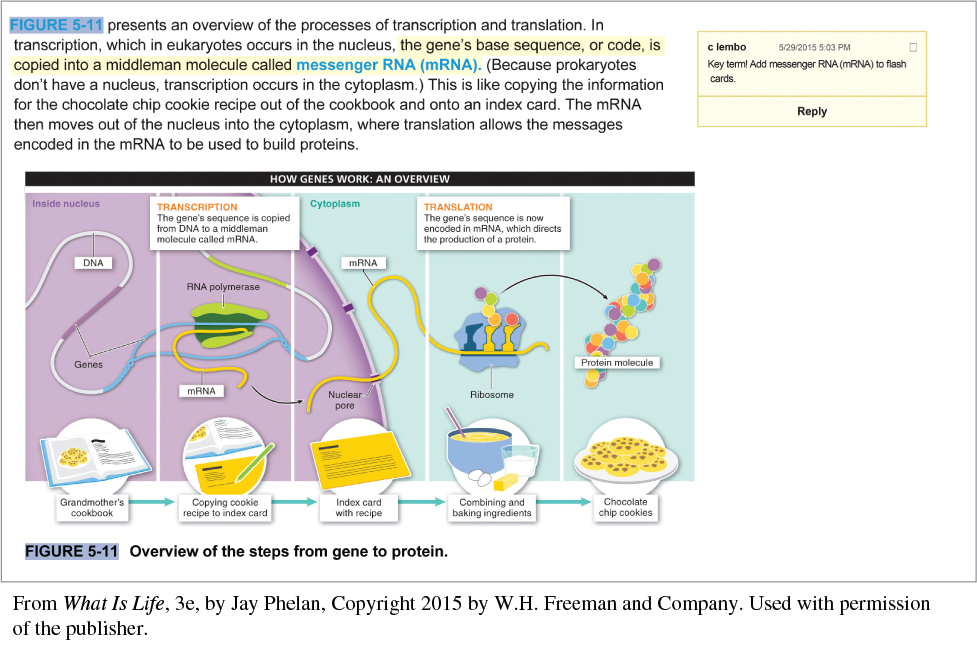

Study diagrams and models. While some sciences rely heavily on symbols and formulas, reading material in others — such as biology, anatomy, and geology — includes more text-based descriptions and diagrams and models. Closely examine these visual elements; the information they contain is often just as valuable as the accompanying text.

Practice. Do the exercises in the book, even if your instructor doesn’t assign them. Practice helps deepen your understanding of the material.

Use flash cards to memorize terms. You’ll encounter many terms in your science courses — for example, the names of organisms in a biology course or the parts of the human body in an anatomy class. Creating flash cards can help you learn and remember these terms. For tips on how to create flash cards, see the memory and studying chapter.

FOR DISCUSSION: Let students know that reading math and science material can be intimidating for many people. Ask students: How might the methods presented here help you read with more concentration? Has anyone tried any of these methods? Did they help? In which of your current classes might these methods be helpful?

Read Journal Articles

Have you heard of the New England Journal of Medicine, Science, or Nature? These are examples of well-known journals — scholarly magazines that publish academic and scientific papers, many of which are written by college professors. In journal articles, professors describe research they’re conducting, share new ideas or theories, summarize findings from a broad area of research, or present original works such as poetry or short stories. You’ve been reading information from journal articles throughout this book: Each Spotlight on Research describes findings that came from a journal article.

141

142

Journal articles are packed with useful information, but they can be more complex than other sources. To read and understand them, you have to know which parts of the article to focus on. Many articles, particularly research articles, have the following sections:

CONNECT

TO MY CAREER

What types of materials would you need to read in your dream job (for example, papers, manuals, blog posts)? If you’re not sure, ask an instructor or do some research to find out. Then list two techniques from this chapter that you believe could help you read those materials more effectively.

Abstract: a paragraph summarizing the article

Introduction: a review of previous research that supports the study and a description of the research questions, often called hypotheses

Methods: a description of what the authors studied and how they studied it

Results: a description of the statistical analysis used to answer the research questions

Discussion: a written summary of the findings or answers to the research questions

You can follow these steps to understand the material in a research article.

Read the abstract and state the article’s main idea in your own words. Once you can do this, you’re ready to read the article itself.

Read the introduction, focusing on the hypotheses at the end of this section. Make sure you know what questions the authors are trying to answer.

Read the discussion, focusing on the first few paragraphs. The authors will likely state the answers to the research questions in prose form (as opposed to statistical form, which often appears in the results section).

Once you understand the research results from the discussion, read the methods and results sections to see more clearly how the authors came to their conclusions.

ACTIVITY: Most first-year students have had very little exposure to journal articles. Present several examples of articles from various disciplines, then select one article to review in more depth. For example, you might read the abstract with the class, pointing out specific strategies for comprehension, and then review the introduction, methods, results, and discussion.

Journal articles are written primarily for other college professors, researchers, and experts in the field, so don’t worry if you feel confused or overwhelmed at first: you’re probably not the only one. Ask for help when you need it. Being able to read and understand even the basic ideas in a journal article is a useful skill, so it’s worth investing time now in learning how to do it.

Read Online Course Materials

If you’re taking an online class for the first time this term, you may be a bit worried. Does the class have more required reading than your face-to-face classes? Is it a hassle to access the readings online? These are legitimate concerns, but here’s good news: You can use a few powerful strategies to handle your online course reading.

Be prepared to do more reading. It’s true that online classes require more reading, because you don’t spend as much time in class listening to lectures. Now that you know, you can plan in advance how to complete all your reading on time.

Create your own schedule. If your online class doesn’t have regular reading assignments or quizzes to help you stay on track, build your own reading schedule — then stick to it.

143

Make sure you can access online materials. If you have to access reading materials online, make sure you can do so when the class begins. If you run into any difficulties, ask the instructor for help right away. That way, you’ll be confident you can access what you need to complete your assignments.

Learn how to mark up text online. If you’re reading online, learn how to mark up text using the tools available with your program or device. Documents in PDF format, for instance, often allow you to highlight text and make notes in the margins. E-books frequently have the same features (see Figure 6.6). In addition, when you read electronically, you often have access to a search function, which allows you to find something you wrote in a note or to search for a specific term.

Consider printing out materials. If your reading materials are provided electronically but you prefer to annotate them in paper form, investigate whether you can print them out.

Read and respond to online posts. You’ll often be required to read and respond to other students’ online posts in discussion boards for the course. Take time to read and reflect on the posts. You can learn a lot from what others have to say.

WRITING PROMPT: Ask students to think of a time when a classmate said or wrote something that made them look at information in a different way. How did it change their perspective? What did they learn? How can they be open to other points of view in class?

144