13.2 Perceiving and Evaluating the Self

10

How does the rouge test of self-recognition work? What has been learned from that test?

Self-awareness is often described as one of the hallmarks of our species. At about 18 months of age, human infants stop reacting to their image in a mirror as if it were another child and begin to treat it as a reflection of themselves (Lewis & Brooks-Gunn, 1979; Kärtner et al., 2012). If a researcher surreptitiously places a bright red spot of rouge (make-up known nowadays as blush) on the child’s nose or cheek before placing the child in front of the mirror, the 18-month-old responds by touching his or her own nose or cheek to feel or rub off the rouge (see Figure 13.4). A younger child, by contrast, touches the mirror or tries to look behind it to find the child with the red spot.

512

We’re not the only species to pass the rouge test. The great apes (chimpanzees, orangutans, and a few gorillas; Gallup, 1979; Suddendorf & Whiten, 2001), dolphins (Reiss & Marino, 2001), elephants (Plotnik et al., 2006), and magpies (Prior et al., 2008) are able to recognize themselves in mirrors, but, so far, no other species. For chimpanzees, at least, the capacity for self-recognition seems to depend on social interaction. In one study, chimps raised in isolation from others of their kind did not learn to make self-directed responses to their mirror images, whereas those raised with other chimps did (Gallup et al., 1971). Many psychologists and sociologists have argued that the self-concept, for humans as well as chimps, is fundamentally a social product. To become aware of yourself, you must first become aware of others of your species and then become aware, perhaps from the way others treat you, that you are one of them. In humans, self-awareness includes awareness not just of the physical self, reflected in mirror images, but also of one’s own personality and character, reflected psychologically in the reactions of other people.

Seeing Ourselves Through the Eyes of Others

11

According to Cooley, what is the “looking glass” with which we evaluate ourselves?

Many years ago the sociologist Charles Cooley (1902/1964) coined the term looking-glass self to describe what he considered to be a very large aspect of each person’s self-concept. The “looking glass” to which he referred is not an actual mirror but other people who react to us. He suggested that we all naturally infer what others think of us from their reactions, and we use those inferences to build our own self-concepts. Cooley’s basic idea has been supported by much research showing that people’s opinions and attitudes about themselves are very much affected by the opinions and attitudes of others.

Effects of Others’ Appraisals on Self-Understanding and Behavior

12

What are Pygmalion effects in psychology, and how were such effects demonstrated in elementary school classrooms?

The beliefs and expectations that others have of a person—whether they are initially true or false—can to some degree create reality by influencing that person’s self-concept and behavior. Such effects are called self-fulfilling prophecies or Pygmalion effects.

Pygmalion was the mythical Roman sculptor, in Ovid’s story, who created a statue of his ideal woman and then brought her to life by praying to Venus, the goddess of love. More relevant to the point being made here, however, is George Bernard Shaw’s revision of the myth in his play Pygmalion (upon which the musical My Fair Lady was based). In the play, an impoverished Cockney flower seller, Eliza Doolittle, becomes a “fine lady” largely because of the expectations of others. Professor Higgins assumes that she is capable of talking and acting like a fine lady, and Colonel Pickering assumes that she is truly noble at heart. Their combined actions toward Eliza lead her to change her own understanding of herself, and therefore her behavior, so that the assumptions become reality. Psychological research indicates that such effects are not confined to fiction.

Pygmalion in the Classroom In a classic experiment, Robert Rosenthal and Lenore Jacobson (1968) led elementary school teachers to believe that a special test had predicted that certain students would show a spurt in intellectual growth during the next few months. Only the teachers were told of the supposed test results, not the students. In reality, the students labeled as “spurters” had been selected not on the basis of a test score but at random. Yet, when all the students were tested 8 months later, the “spurter” students showed significantly greater gains in IQ and academic performance than did their classmates. These were real gains, measured by objective tests, not just perceived gains. Somehow, the teachers’ expectations that certain children would show more intellectual development than other children created its own reality.

513

Subsequent replications of this Pygmalion in the classroom effect provided clues concerning its mechanism. Teachers became warmer toward the selected students, gave them more time to answer difficult questions, gave them more challenging work, and noticed and reinforced more often their self-initiated efforts (Cooper & Good, 1983; Rosenthal, 1994). In short, either consciously or unconsciously, they created a better learning environment for the selected students than for other students. Through their treatment of them, they also changed the selected students’ self-concepts. The students began to see themselves as more capable academically than they had before, and this led them to work harder to live up to that perception (Cole, 1991; Jussim, 1991).

More recently, many experiments have demonstrated the Pygmalion effect with adults in various business and management settings as well as with children in school. When supervisors are led to believe that some of their subordinates have “special promise,” those randomly selected subordinates in fact do begin to perform better than they did before (Eden, 2003; Natanovich & Eden, 2008). Again, these effects appear to occur partly from the extra attention and encouragement that the selected subordinates get and partly from the change in the subordinates’ self-concepts in relation to their work.

13

What evidence supports the idea that simply attributing some characteristic to a person can, in some cases, lead that person to take on that characteristic?

Changing Others’ Behavior by Directly Altering Their Self-Concepts In the experiments just described, changes in subjects’ self-concepts resulted from differences in the way that teachers or supervisors treated them. Other experiments have shown that simply telling others that they are a certain kind of person can, in some cases, lead them to behave in ways that are consistent with the attribute that they are told they have.

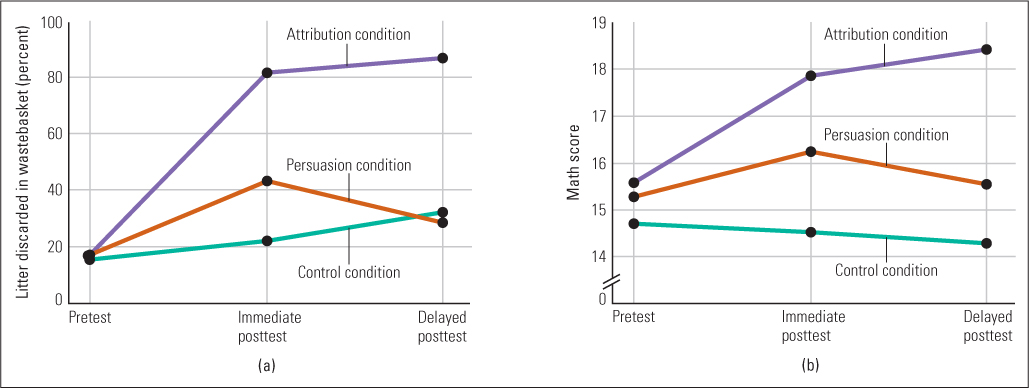

In one such experiment, some elementary school children were told in the course of classroom activity that they were neat and tidy (attribution condition); others were encouraged to become more neat and tidy (persuasion condition); and still others were given no special treatment (control condition). The result was that those in the attribution condition became significantly neater, as measured by the absence of littering, than did those in either of the other conditions (Miller et al., 1975). Similarly, children who were told that they were good at math showed greater subsequent improvements in math scores than did those who were told that they should try to become good at math (see Figure 13.5). In these experiments the change in behavior presumably occurred because of a direct effect of the appraisals on the children’s self-concepts, which they then strove to live up to.

514

Of course, people’s self-concepts are not always as easily molded as the experiments just cited might suggest. In cases where an attribution runs directly counter to a person’s strong beliefs about himself, the attributions can backfire. In some experiments, people have been observed to respond in ways that seem designed to correct what they believed to be mistaken perceptions of them—Pygmalion in reverse (Swann, 1987). For example, a person who has a strong self-image of being an artistic type, and not a scientific type, may react to an attribution that he is good at science by performing more poorly on the next science test than he did before.

Self-Esteem as an Index of Others’ Approval and Acceptance

Our self-concepts have a strong evaluative component, which psychologists refer to as self-esteem. Self-esteem, by definition, is one’s feeling of approval, acceptance, and liking of oneself. It is usually measured with questionnaires in which people rate the degree to which they agree or disagree with such statements as, “On the whole, I am satisfied with myself” and “I feel that I have a number of good qualities” (Tafarodi & Milne, 2002).

14

What is the sociometer theory of self-esteem, and what evidence supports it?

We experience self-esteem as deriving from our own judgments about ourselves, but, according to an influential theory proposed by Mark Leary (1999, 2005), these judgments actually derive primarily from our perceptions of others’ attitudes toward us. The theory is referred to as the sociometer theory because it proposes that self-esteem acts like a meter to inform us, at any given time, of the degree to which we are likely to be accepted or rejected by others. According to the sociometer theory, what you experience as your self-esteem at this very moment largely reflects your best guess about the degree to which other people, whom you care about, respect and accept you. As partial support of the sociometer theory, Leary and others have cited the following lines of evidence:

- Individual differences in self-esteem correlate strongly with individual differences in the degree to which people believe that they are generally accepted or rejected by others (Leary et al., 2001).

- When people were asked to rate the degree to which particular real or hypothetical occurrences in their lives (such as rescuing a child, winning an award, or failing a course) would raise or lower their self-esteem, and also to rate the degree to which those same occurrences would raise or lower other people’s opinions of them, the two sets of ratings were essentially identical (Leary et al., 2001).

- In experiments, and in correlational studies involving real-life experiences, people’s self-esteem increased after praise, social acceptance, or other satisfying social experiences and decreased after evidence of social rejection (Baumeister et al., 1998; Denissen et al., 2008; Leary et al., 2001).

- Feedback about success or failure on a test had greater effects on self-esteem if the person was led to believe that others would hear of this success or failure than if the person was led to believe that the feedback was private and confidential (Leary & Baumeister, 2000). This may be the most compelling line of evidence for the theory because if self-esteem depended just on our own judgments about ourselves, then it shouldn’t matter whether or not others knew how well we did.

The sociometer theory was designed to offer an evolutionary explanation of the function of self-esteem. From an evolutionary perspective, other people’s views of us matter a great deal. Our survival depends on others’ acceptance of us and willingness to cooperate with us. A self-view that is greatly out of sync with how others see us could be harmful. If I see myself as highly capable and trustworthy, but nobody else sees me that way, then my own high self-esteem will seem foolish to others and will not help me in my dealings with them. A major evolutionary purpose of our capacity for self-esteem, according to the sociometer theory, is to motivate us to act in ways that promote our acceptance by others. A decline in self-esteem may lead us to change our ways in order to become more socially acceptable, or it may lead us to seek a more compatible social group that approves of our ways. Conversely, an increase in self-esteem may lead us to continue on our present path, perhaps even more vigorously than before.

515

Actively Constructing Our Self-Perceptions

Although other people’s views of us play a large role in our perceptions of ourselves, we do not just passively accept those views. We actively try to influence others’ views of us, and in that way we also influence our own self-perceptions. In fact, rather than viewing the self as a static entity, some theorists view it as a dynamic one, shifting from one state to another at times when the self-structure is poorly integrated, but resisting the tendency to change in the face of inconsistent information when the self-structure is well integrated (Nowak et al., 2000; Vallacher et al., 2002). In addition, we compare ourselves to others as a way of defining and evaluating ourselves, and we often bias those comparisons by giving more weight to some pieces of evidence than to others.

Social Comparison: Effects of the Reference Group

In perception everything is relative to some frame of reference, and in self-perception the frame of reference is other people. To see oneself as tall, or conscientious, or good at math, is to see oneself as having that quality compared with other people. The process of comparing ourselves with others in order to identify our unique characteristics and evaluate our abilities is called social comparison. A direct consequence of social comparison is that the self-concept varies depending on the reference group, the group against whom the comparison is made. If the reference group against which I evaluated my height were made up of professional basketball players, I would see myself as short, but if it were made up of jockeys, I would see myself as very tall.

15

What is some evidence that people construct a self-concept by comparing themselves with a reference group? How can a change in reference group alter self-esteem?

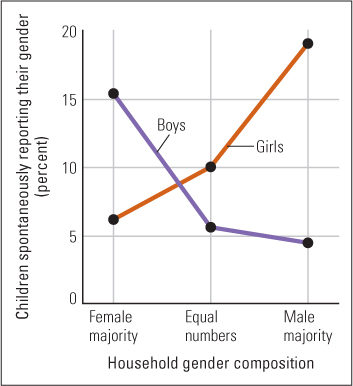

Effect of the Reference Group on Self-Descriptions in one series of studies illustrating the role of the reference group, children’s self-descriptions were found to focus on traits that most distinguished them from others in their group (McGuire & McGuire, 1988). Thus, children in racially homogeneous classrooms rarely mentioned their race, but those in racially mixed classrooms quite commonly did, especially if their race was in the minority. Children who were unusually tall or short compared with others in their group mentioned their height, and children with opposite-gender siblings mentioned their own gender more frequently than did other children (see Figure 13.6). Such evidence suggests that people identify themselves largely in terms of the ways in which they perceive themselves to be different from those around them.

Effect of the Reference Group on Self-Evaluations The evaluative aspect of social comparison can be charged with emotion. We are pleased with ourselves when we feel that we measure up to the reference group and distressed when we don’t. A change of reference group, therefore, can dramatically affect our self-esteem. Many first-year college students who earned high grades in high school feel crushed when their marks are only average or less compared with those of their new, more selective reference group of college classmates. Research conducted in many different countries has shown that academically able students at nonselective schools typically have higher academic self-concepts than do equally able students at very selective schools (Marsh et al., 2008), a phenomenon aptly called the big-fish-in-little-pond effect. The difference reflects the difference in the students’ reference groups.

516

William James (1890/1950), reflecting on extreme instances of selective comparison, wrote: “So we have the paradox of the man shamed to death because he is only the second pugilist [boxer] or second oarsman in the world. That he is able to beat the whole population of the globe minus one is nothing; he has ‘pitted’ himself to beat that one and as long as he doesn’t do that nothing else counts” (p. 310).

In a follow-up of James’s century-old idea, Victoria Medvec and her colleagues (1995) analyzed the televised broadcasts of the 1992 Olympics for the amounts of joy and agony expressed by the silver and bronze medalists after each event. The main finding was that the silver medalists (the second-place finishers) showed, on average, less joy and more agony than did the bronze medalists (the third-place finishers), whom they had defeated. (This has been confirmed by looking at silver and bronze medal winners in more recent Olympics as well; Matsumoto & Willingham, 2006.) The researchers explained this finding by suggesting that the groups were implicitly making different comparisons. The silver medalists had almost come in first, so the prominent comparison to them was between themselves and the gold medalists, and in that comparison they were losers. In contrast, the bronze medalists had barely made it into the group that received a medal at all, so the prominent comparison in their minds was between themselves and the nonmedalists, and in that comparison they were winners.

A subsequent study of medalists in the 2000 Olympics, by other researchers, produced a somewhat different result (McGraw et al., 2005). That study took account of how well each medalist had expected to perform, and the main finding was that those who performed better than expected were happier than those who performed worse than expected, regardless of which medal they won. Bronze medalists who had expected to win no medal were happier than silver medalists who had expected to win the gold. But bronze medalists who had expected either gold or silver were less happy than silver medalists who had expected either bronze or no medal.

James (1890/1950) wrote that a person’s self-esteem is equal to his achievements divided by his pretensions. By pretensions, he was referring to the person’s self-chosen goals and reference groups. This formula is helpful in explaining why high achievers typically do not have markedly higher levels of self-esteem than do people who achieve much less (Crocker & Wolfe, 2001). With greater achievements come greater aspirations and ever more elite reference groups for social comparison.

517

Enhancing Our Views of Ourselves

The radio humorist Garrison Keillor describes his mythical town of Lake Wobegon as a place where “all the children are above average.” We smile at this statistical impossibility because we recognize the same bias in those around us and may vaguely recognize it in ourselves. Repeated surveys have found that most college students rate themselves as better students than the average college student, and in one survey 94 percent of college instructors rated themselves as better teachers than the average college instructor (Alicke et al., 1995; Cross, 1977). Indeed, at least in North America and Western Europe, people tend to rate themselves unduly high on practically every dimension that they value (Roese & Olson, 2007). It is useful to have relatively accurate views of ourselves, but it feels good to think well of ourselves, so most of us skew our self-evaluations in positive directions. We maintain our unduly high self-evaluations by treating evidence about ourselves differently from the way we treat evidence about others. Here are four means by which we do that.

16

What are four means by which people build and maintain inflated views of themselves?

Attributing Our Successes to Ourselves, Our Failures to Something Else One way that we maintain a high view of ourselves is to systematically skew the attributions we make about our successes and failures. Earlier in this chapter we described the person bias—the general tendency to attribute people’s actions, whether good or bad, to internal qualities of the person and to ignore external circumstances that constrained or promoted the actions. That bias applies when we think about other people’s actions, but not when we think about our own actions. When we think about our own actions a different bias takes over, the self-serving attributional bias, defined as a tendency to attribute our successes to our own inner qualities and our failures to external circumstances. This bias has been demonstrated in countless experiments, with a wide variety of different kinds of tasks (Mezulis et al., 2004).

In one demonstration of this bias, students who performed well on an examination attributed their high grades to their own ability and hard work, whereas those who performed poorly attributed their low grades to bad luck, the unfairness of the test, or other factors beyond their control (Bernstein et al., 1979). In another study, essentially the same result was found for college professors who were asked to explain why a paper they had submitted to a scholarly journal had been either accepted or rejected (Wiley et al., 1979). Our favorite examples of the self-serving attributional bias come from people’s formal reports of automobile accidents, such as the following (quoted by Greenwald, 1980): “The telephone pole was approaching. I was attempting to swerve out of its way when it struck my front end.” Clearly, a reckless telephone pole caused this accident; the skillful driver just couldn’t get out of its way in time.

Accepting Praise at Face Value Most of us hear many more positive statements about ourselves than negative statements. Norms of politeness as well as considerations of self-interest encourage people to praise each other and inhibit even constructive criticism. “If you can’t say something nice, say nothing at all” is one of our mores. Since we build our self-concepts at least partly from others’ appraisals, we are likely to construct positively biased self-concepts to the degree that we believe the praise we hear from others. A number of experiments have shown that most people tend to discount praise directed toward others as insincere flattery or ingratiation, but accept the same type of praise directed toward themselves as honest reporting (Vonk, 2002).

Remembering Successes, Forgetting Failures Another means by which most of us maintain inflated views of ourselves involves selective memory. Research has shown that people generally exhibit better long-term memory for positive events and successes in their lives than for negative events and failures (D’Argembeau & Van der Linden, 2008). The same bias does not occur in memory for the successes and failures of other people. This positivity bias is especially strong in older adults (Mather et al., 2004).

518

Overinflated Sense of Self Although having a slightly inflated sense of ourselves may be adaptive, when one’s self-concept is far in excess of one’s accomplishments, the outcome may be maladaptive. This can happen when a child’s parents provide nothing but praise to their children—deserved or not—resulting in an overinflated sense of self and an unrealistically high level of self-esteem (Lamborn et al., 1991).

Over the past several decades the professed self-esteem of American adolescents has been increasing, promoted in large part by a societal emphasis on building self-esteem (Twenge, 2006; Twenge & Campbell, 2001). Although self-esteem is generally associated with better academic achievement and psychological health, an unrealistically high level of self-esteem can backfire. For example, American adolescents’ self-esteem with respect to academic performance has increased over recent decades but has been accompanied by declines in academic performance and increases in adjustment problems, including depression (see Berk, 2005). For instance, in a comparison of 40 developed countries, American teenagers ranked slightly below the average in mathematics achievement but they were first in math self-concept (OECD, 2004). Overinflated self-esteem and its negative consequences seem to be especially prevalent among children from more affluent homes, whose parents strive to protect their offspring from feelings of failure in order to promote their sense of self-worth (Levine, 2006).

According to Martin Seligman (1998), the “self-esteem movement” in the United States resulted in young people who felt good about themselves without achievements to warrant their feelings. This is an unstable foundation on which to build a personality and can lead to depression when they encounter failure.

Self-Control

To this point we’ve been focusing on one’s “sense of self,” but there’s another important way of viewing the self, and that is as the agent that intentionally directs action. We make decisions, evaluate and choose among our options in a particular situation, and otherwise behave purposively. When we perceive that someone is trying to control our behavior, we sometimes act in opposition, termed a reactance effect, in order to exert some self-control (Brehm, & Brehm, 1981). Self-control is related to executive functions. As you may recall from earlier chapters, executive functions involve several lower-level cognitive abilities (working memory, inhibition, and task switching) that are essential in planning, regulating behavior, and performing complex cognitive tasks (Miyake & Friedman, 2012). Executive functions are important not just for performing academic-type tasks, but also for most complex real-world tasks. For example, individual differences in executive function are related to being faithful to a romantic partner (Klauer et al., 2010) and sticking with diet and exercise regimes (Hall et al., 2008).

Don’t Eat the Marshmallow!

17

Why might resisting temptation at 4 years of age predict important psychological outcomes in adolescence and adulthood?

One way of assessing self-control is to present people with an attractive option they are supposed to avoid to see how well they are at resisting temptation. We do this when we diet. The chocolate cake in the refrigerator “calls” to you; can you resist, or do you succumb to the temptation and promise to start your diet for real tomorrow?

One classic series of studies of resistance to temptation has been over 40 years in the making (Mischel, 2012; Mischel & Ayduk, 2011; Mischel et al., 1972). In these studies, 4-year-old children sat at a table with an experimenter. On the table were a bell and two treats (marshmallows in the original studies). The experimenter explained to the children that they would eventually receive a treat, but first he had to leave the room for a while. Children were then told “if you wait until I come back by myself then you can have this one [two marshmallows]. If you don’t want to wait you can ring the bell and bring me back any time you want to. But if you ring the bell then you can’t have this one [two marshmallows], but you can have that one [one marshmallow]” (Shoda et al., 1990, p. 980). Some children waited for up to 15 minutes, but most rang the bell, or in other studies ate a single marshmallow after some delay rather than waiting to get two. What’s special about these studies, however, is that the researchers re-evaluated many of the child subjects again as adolescents (Eigsti et al., 2006; Shoda et al., 1990) and a third time when they were in their early 30s (Ayduk et al., 2000, 2008; Schlam et al., 2013). The longer 4-year-olds were willing to wait before taking their treat, the higher were their SAT scores and school grades, the better they were able to concentrate and deal with stress as teenagers, and, as adults, they had healthier body mass indexes, a higher sense of self-worth, and were less vulnerable to psychosocial maladjustment. Interestingly, these simple latency measures taken at 4 years of age predicted self-regulating abilities nearly 30 years later. Similar findings, predicting adult outcomes with respect to physical health, substance dependence, personal finances, and criminal behavior based on childhood measures of self-control, have been reported in a 30-year longitudinal study of more than 1,000 subjects from Dunedin, New Zealand (Moffitt et al., 2011).

519

Ego Depletion

18

How does the concept of ego depletion explain the reduction in self-control after performing a difficult task?

If self-control can be viewed as a special case of executive functions, then it is a mentally effortful activity that is potentially available to conscious awareness, and its execution consumes a person’s limited mental resources (Vohs, 2010). Assuming this, Roy Baumeister and his colleagues reasoned that exerting self-control on one task would deplete some of one’s limited mental resources, resulting in poorer self-control on subsequent tasks (Baumeister et al., 1998; Mauraven & Baumeister, 2000). Baumeister referred to this as ego depletion, and there have now more than 100 published experiments assessing this phenomenon (Inzlicht & Schmeichel, 2012).

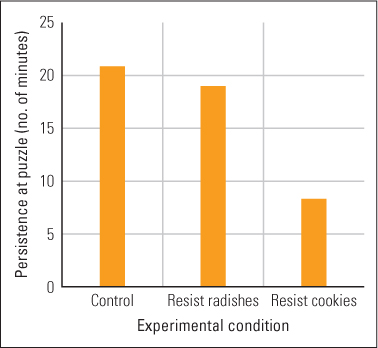

In the pioneering study, Baumeister and his colleagues (1998) sat college students at a table set for a taste test with two plates of food: radishes and freshly baked chocolate-chip cookies. Half of the subjects were told they could eat the radishes but not the cookies, and the other half were told the opposite. After 5 minutes of tasting the target food, the subjects were then given a challenging puzzle to work at, as was a control group of college students who didn’t participate in the “taste test” part of the experiment.

Figure 13.7 shows the number of minutes subjects in each of the three groups (resist the cookies, resist the radishes, control) worked at the difficult puzzle. As you can see, college students who had to resist eating the cookies persisted at the puzzle significantly less than those who had to resist the radishes or those in the control group. According to Baumeister and his colleagues, subjects in the “resist the cookies” condition had to expend considerable mental effort in resisting the cookies and as a result they didn’t have as much willpower left to persist on the puzzle as the less-challenged subjects in the “resist the radishes” group. This basic pattern of ego depletion has been replicated repeatedly in a variety of contexts (Inzlicht & Schmeichel, 2012), and subsequent research has convincingly demonstrated that people find it hard to exert the mental effort necessary for self-control when they are stressed, tired, frustrated, or sad (Masicampo, & Baumeister, 2011; Tice et al., 2001; Vohs et al., 2005).

520

Baumeister and his colleagues believe that “loss of mental energy” is not simply a metaphor, but that ego depletion is caused by the actual depletion of a form of glucose in the brain. In a series of experiments, subjects who were given sweeteners that provide glycogen to the brain showed less ego depletion than subjects who are given artificial sweeteners that didn’t provide an energy brain-boost (Gailliot & Baumeister, 2007; Gailliot et al., 2007). This interpretation remains somewhat controversial (perhaps the sugar activates other areas of the brain associated with motivation; Molden et al., 2012), but the interpretation that self-control is costly in terms of mental effort, and that that cost is paid by reduced self-control on subsequent tasks, is one with important implications for everyday life.

Free Will

19

How might a belief in free will promote prosocial behavior?

Perhaps the most obvious expression of self-control is in the perception of free will. When we are able to regulate our behavior, we perceive that we are behaving purposively, of our own volition. We also assume other people’s behavior is freely expressed—that they act in a certain way for a reason with a particular goal in mind. We all engage in “thoughtless” behavior from time to time, but we interpret most of our behavior and the behavior of other people as being deliberate and of “their own free will.” Legal systems are based on this presumption, and a perpetrator of a crime may be found “not guilty” if it can be demonstrated that he or she was unaware of what he or she was doing when the criminal act was committed. We stated in Chapter 11 that a foundational ability of human social interaction was infants beginning to see other people as intentional agents (p. 422), engaging in behaviors purposively with some goal in mind.

We do not mean to imply, as do some philosophers, that free will is some psychic process independent of the brain (Montague, 2008). Rather, we follow Baumeister’s (2010) definition of free will as “a particular form of action control that encompasses self-regulation, rational choice, planned behavior, and initiative” (p. 24). Baumeister further proposed that free will, in the form of self-control, evolved as a result of pressure from living in increasingly complex social groups. As our hominin ancestors became increasingly dependent on one another for their survival, greater self-control was necessary in order to inhibit aggressive and sexual urges, which are counterproductive to a smooth-running cooperative group (Bjorklund & Harnishfeger, 1995). This increase in self-control was accompanied by an increase in self-awareness and thus the perception of free will.

Although most people believe in free will, we all realize that there are degrees to which our behavior is truly “intentional.” When we are tired or under the influence of some drugs, for example, most people recognize that our behavior is not fully under our control. Moreover, many scientists and philosophers argue that free will is an illusion, and that human behavior can be reduced to patterns of neural firings based on one’s genetics and past experiences (Crick, 1994). We have no intention to discuss whether free will is real or illusionary here, but rather to show that it matters what people believe about free will when it comes to some socially important behaviors. For example, several researchers have shown that people are more apt to cheat and act aggressively, and less likely to offer help to someone in need, when their belief in free will is reduced (Baumeister et al., 2009; Vohs & Schooler, 2008). For example, in one set of experiments Kathleen Vohs and Jonathan Schooler (2008) had college students read one of two excerpts from Francis Crick’s (1994) book The Astonishing Hypothesis. (Crick was the Nobel-Prize winning co-discoverer of the role that DNA plays in inheritance, so his opinion should have carried some weight with the subjects.) One passage emphasized how most scientists believe that free will is an illusion and merely a by-product of the activity of the brain. Others read a passage that made no mention of free will. Subjects later solved some math problems on a computer, which, the experimenter pointed out, had a glitch in it. Sometimes the computer would provide the correct answer while they were still working on the problem. The subjects were told that they could prevent this from happening by pressing the space bar when the problem first appeared on the screen. The experimenter would not know when this happened, but subjects should solve the problems honestly. In actuality, the experimenter knew exactly when the computer “glitch” would occur and kept track of how honest subjects were on the math test. Subjects who read the anti-free-will passage were significantly more likely to cheat (70 percent of possible trials) than were subjects who read the control passage (48 percent). Similar results were found in a second experiment.

521

In related experiments using the same biasing technique used in the Vohs and Schooler (2008) study, undergraduate students who were biased to disbelieve in free will were later less willing to offer help and more likely to act aggressively toward others than students in control conditions (Baumeister et al., 2009). The authors of these studies argued that a deterministic (that is, anti-free-will) view of the human mind results in reduced moral behaviors. Belief in free will—that one is in control and thus responsible for one’s actions—may be one mechanism that promotes prosocial behavior and may have been selected over the course of human evolution to promote more harmonious life in a human group (Bering & Bjorklund, 2007).

SECTION REVIEW

The social world around us profoundly affects our understanding of ourselves.

Seeing Ourselves Through Others’ Eyes

- Classroom experiments have demonstrated Pygmalion effects, in which adults’ expectations about children’s behavior created the expected behavior. Such effects occur at least partly by altering the children’s self-concepts.

- A variety of evidence supports the sociometer theory, which states that self-esteem reflects the level of acceptance or rejection we believe we can expect from others.

Active Construction of Self-Perceptions

- We perceive ourselves largely through social comparison—comparing ourselves to others. Our judgments and feelings about ourselves depend on the reference group to which we compare ourselves, as illustrated by the big-fish-in-little-pond effect.

- At least in North America and Western Europe, people tend to enhance their views of themselves through such means as making self-serving attributions (attributing success to the self and failure to the situation), accepting praise at face value, remembering successes more than failures, and defining their own criteria for success.

Self-Control

- Self-control, or self-regulation, is related to executive functions and influences how people behave in everyday settings. Self-control on a resistance to temptation task predicts many aspects of psychological functioning into adulthood.

- Ego depletion occurs when performing one effortful task reduces one’s self-control on a subsequent task, and may be related to actual depletion of glycogen in the brain.

- Belief in free will may promote prosocial behavior.

522