14.2 Effects of Others’ Examples and Opinions

Other people influence our behavior not just through their roles as observers and evaluators but also through the examples they set. There are two general reasons why we tend to conform to others’ examples.

6

What are two classes of reasons why people tend to conform to examples set by others?

One reason has to do with information and pragmatics. If other people cross bridge A and avoid bridge B, they may know something about the bridges that we don’t know. To be safe, we had better stick with bridge A, too. If other people say rhubarb leaves are poisonous, then to be safe, in the absence of better information, we shouldn’t eat them, and we should probably tell our children they are poisonous. One of the great advantages of social life lies in the sharing of information. We don’t all have to learn everything from scratch, by trial and error. Rather, we can follow the examples of others and profit from trials and errors that may have occurred generations ago. Social influence that works through providing clues about the objective nature of an event or situation is referred to as informational influence.

The other general reason for conforming is to promote group cohesion and acceptance by the group. Social groups can exist only if some degree of behavioral coordination exists among the group members. Conformity allows a group to act as a coordinated unit rather than as a set of separate individuals. We tend to adopt the ideas, myths, and habits of our group because doing so generates a sense of closeness with others, promotes our acceptance by them, and enables the group to function as a unit. We all cross bridge A because we are the bridge A people, and proud of it! If you cross bridge B, you may look like you don’t want to be one of us or you may look strange to us. This kind of social influence, which works through the person’s desire to be part of a group or to be approved by others, is called normative influence.

545

Conformity to group norms is found early in development. In fact, 2- and 3-year-old children, when shown a demonstration of a puppet performing a novel set of actions, will correct a person who fails to use the same words and actions in performing the task, with some 3-year-olds saying things like (“It doesn’t work like that. You have to do it like this”) (Rakoczy et al., 2008, 2009). That is, young children will attempt to enforce social norms on others, illustrating that they recognize what is normative and that others should follow the rules (Schmidt & Tomasello, 2012). Conformity to peer pressure becomes especially important for children during the school years, peaking in early adolescence (Berndt, 1979; Gavin & Furman, 1989).

Asch’s Classic Conformity Experiments

Under some conditions, conformity can lead people to say or do things that are objectively ridiculous, as demonstrated in a famous series of experiments conducted by Solomon Asch in the 1950s. Asch’s original purpose was to demonstrate the limits of conformity (Asch, 1952). Previous research had shown that people conform to others’ judgments when the objective evidence is ambiguous (Sherif, 1936), and Asch expected to demonstrate that they would not conform when the evidence is clear-cut. But his results surprised him and changed the direction of his research.

Basic Procedure and Finding

7

How did Asch demonstrate that a tendency to conform can lead people to disclaim the evidence of their own eyes?

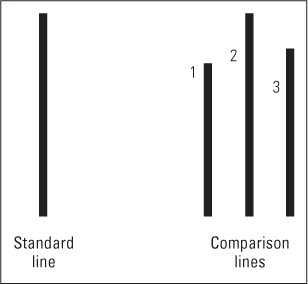

Asch’s (1956) procedure was as follows: A college-student volunteer was brought into the lab and seated with six to eight other students, and the group was told that their task was to judge the lengths of lines. On each trial they were shown one standard line and three comparison lines and were asked to judge which comparison line was identical in length to the standard (see Figure 14.4). As a perceptual task, this was absurdly easy; in previous tests, subjects performing the task alone almost never made mistakes. But, of course, this was not really a perceptual task; it was a test of conformity. Unbeknown to the real subject, the others in the group were confederates of the experimenter and had been instructed to give a specific wrong answer on certain prearranged “critical” trials. Choices were stated out loud by the group members, one at a time in the order of seating, and seating had been arranged so that the real subject was always the next to last to respond. The question of interest was this: On the critical trials, would subjects be swayed by the confederates’ wrong answers?

546

Of more than 100 subjects tested, 75 percent were swayed by the confederates on at least one of the 12 critical trials in the experiment. Some of the subjects conformed on every trial, others on only one or two. On average, subjects conformed on 37 percent of the critical trials. That is, on more than one-third of the trials on which the confederates gave a wrong answer, the subject also gave a wrong answer, usually the same wrong answer as the confederates had given. Asch’s experiment has since been replicated dozens of times, in at least 17 different countries (Bond & Smith, 1996). The results reveal some decline in conformity in North America after the 1950s and some variation across cultures, but they still demonstrate a considerable amount of conformity whenever and wherever the experiment is conducted.

Was the Influence Informational or Normative?

8

What evidence led Asch to conclude that conformity in his experiments was caused more by normative than by informational influences?

Did Asch’s subjects conform as a result of informational or normative influence? That is, did the subjects use the majority response as evidence regarding the objective lengths of the lines, or did they conform out of fear of looking different (nonnormative) to the others present? When Asch (1956) questioned the subjects after the experiment, very few said that they had actually seen the lines as the confederates had seemed to see them, but many said that they had been led to doubt their own perceptual ability. They made such comments as: “I thought that maybe because I wore glasses there was some defect”; “At first I thought I had the wrong instructions, then that something was wrong with my eyes and my head”; and “There’s a greater probability of eight being right [than one].” Such statements suggest that to some degree the subjects did yield because of informational influence; they may have believed that the majority was right.

But maybe these comments were, to some degree, rationalizations. Maybe the main reasons for conformity had more to do with a desire to be liked or accepted by the others (normative influence) than with a desire to be right. To test this possibility, Asch (1956) repeated the experiment under conditions in which the confederates responded out loud as before, but the subjects responded privately in writing. To accomplish this, Asch arranged to have the real subjects arrive “late” to the experiment and be told that although no more subjects were needed, they might participate in a different way by listening to the others and then writing down, rather than voicing aloud, the answer they believed to be correct. In this condition, the amount of conformity dropped to about one-third of that in the earlier experiments. This indicates that the social influence on Ash’s original subjects was partly informational but mostly normative. When subjects did not have to respond publicly, so that there was no fear of appearing odd to the other subjects, or of acting like they were rejecting the others’ views, their degree of conformity dropped sharply. Many similar experiments, since Asch’s, have likewise shown that conformity decreases when subjects can respond privately rather than publicly (Bond, 2005).

It’s interesting to note that the majority of Asch’s subjects conformed on some trials but not on others. One interpretation is that they were hedging their bets. On trials in which they answered as they saw it, they were portraying themselves as independent truth-tellers; and on trials in which they conformed they were informing the others in the group that they were not against them—they were trying to see things as the others saw them (Hodges & Geyer, 2006).

The Liberating and Thought-Provoking Influence of a Nonconformist

9

What valuable effects can a single nonconformist have on others in the group?

When Asch (1956) changed his procedure so that a single confederate gave a different answer from the others, the amount of conformity on the line-judging task dropped dramatically—to about one-fourth of that in the unanimous condition. This effect occurred regardless of how many other confederates there were (from 2 to 14) and regardless of whether the dissenter gave the right answer or a different wrong answer from the others. Any response that differed from the majority encouraged the real subject to resist the majority’s influence and to give the correct answer.

Since Asch’s time, other experiments, using more difficult tasks or problems than Asch’s, have shown that a single dissension from the majority can have beneficial effects not just through reducing normative pressure to conform but also through informational means, by shaking people out of their complacent view that the majority must be right (Nemeth, 1986). When people hear a dissenting opinion, they become motivated to examine the evidence more closely, and that can lead to a better solution.

547

Norms as Forces for Helpful and Harmful Actions

In Asch’s experiments, the social context was provided by the artificial situation of a group of people misjudging the length of a line. In everyday life, the social context consists not just of what we hear others say or see them do, but also of the various telltale signs that inform us implicitly about which behaviors are normal in the setting in which we find ourselves, and which behaviors are not. The norms established by such signs can have serious consequences for all of us.

The “Broken Windows” Theory of Crime

10

According to the “broken windows” theory, how do normative influences alter the crime rate? How was the theory tested with field experiments?

During the 1990s, New York City saw a precipitous drop in crime. The rates of murders and felonies dropped, respectively, to one-third and one-half of what they had been in the 1980s. A number of social forces contributed to the change, no doubt, but according to some analyses, at least some of the credit goes to the adoption of new law-enforcement policies recommended by George Kelling, a criminologist who was hired by the city as a consultant (Gladwell, 2000).

Kelling was already known as a developer of the broken windows theory of crime (Kelling & Coles, 1996). According to this theory, crime is encouraged by physical evidence of chaos and lack of care. Broken windows, litter, graffiti, and the like send signals that disrespect for law, order, and the rights of residents is normal. People regularly exposed to such an environment can develop a “law of the jungle” mentality, which leads not just to more petty crime but to thefts and murders as well. By physically cleaning up the subways, streets, and vacant buildings and by cracking down on petty crime, New York City authorities helped create a social environment that signaled that law and order are normal and law-breaking is abnormal. That signal may have helped to reduce crimes of all sorts, ranging from littering to murder. People are motivated to behave in ways they see as normal.

More recently, researchers in Groningen, Netherlands, tested the broken windows theory with a series of field experiments (Keizer et al., 2008). In each experiment, they observed a public area in the city in each of two conditions. In one condition, the order condition, they made certain that the area was cleaned up of all litter and graffiti. In the other condition, the disorder condition, they deliberately spread litter or graffiti around that same area (see Figure 14.5). In each condition, they observed inconspicuously for instances of littering or petty crime by people passing through. In one experiment, for example, they set up the possibility of stealing by placing a partly opened envelope with a 5-euro note sticking out of the opening of a mailbox. They found that 27 percent of passersby stole the money from the mailbox if there was graffiti on the mailbox, but only 13 percent stole it if there was no graffiti. In another experiment, 82 percent of passersby ignored an official-looking sign telling them not to walk along a particular path in the disordered condition, compared to 27 percent in the ordered condition. Of course, the researchers couldn’t study major crimes in this way, but it is not hard to imagine how a proliferation of minor crimes and the attitude that they are normal could escalate into larger crimes.

Dr. Kees Keizer Behavioral and Social Sciences University of Groningen

548

Effects of Implicit Norms in Public-Service Messages

11

According to Cialdini, how can public-service messages best capitalize on normative influences? What evidence does he provide for this idea?

Many public-service messages include statements about the large number of people who engage in some undesirable behavior, such as smoking, drunk driving, or littering. According to Robert Cialdini, an expert on persuasion, such messages may undermine themselves. At the same time that they are urging people not to behave in a certain way, they are sending the implicit message that behaving in that way is normal—many people do behave in that way. Cialdini suggests that public-service messages would be more effective if they emphasized that the majority of people behave in the desired way, not the undesired way, and implicitly portrayed the undesired behavior as abnormal.

As a demonstration of this principle, Cialdini (2003) developed a public-service message designed to increase household recycling, and aired it on local radio and TV stations in four Arizona communities. The message depicted a group of people all recycling and speaking disapprovingly of a lone person who did not recycle. The result was a 25 percent increase in recycling in those communities—a far bigger effect than is usually achieved by public-service messages.

In another study, Cialdini (2003) and his colleagues created two signs aimed at decreasing the pilfering of petrified wood from Petrified Forest National Park. One sign read, “Many past visitors have removed petrified wood from the Park, changing the natural state of the Petrified Forest,” and depicted three visitors taking petrified wood. The other sign depicted a single visitor taking a piece of wood, with a red circle-and-bar symbol superimposed over his hand, along with the message, “Please do not remove the petrified wood from the Park, in order to preserve the natural state of the Petrified Forest.” On alternate weekends, one or the other of these signs was placed near the beginning of each path in the park. To measure theft, marked pieces of petrified wood were placed along each path. The dramatic result was that 7.92 percent of visitors tried to steal marked pieces on the days when the first sign was present, compared with only 1.67 percent on the days when the second sign was present. Previous research had shown that, with neither of these signs present but only the usual park injunctions against stealing, approximately 3 percent of visitors stole petrified wood from the park. Apparently, by emphasizing that many people steal, the first sign increased the amount of stealing sharply above the baseline rate; and the second sign, by implying that stealing is rare as well as wrong, decreased it to well below the baseline rate.

Conformity as a Basis for Failure to Help: The Passive Bystander Effect

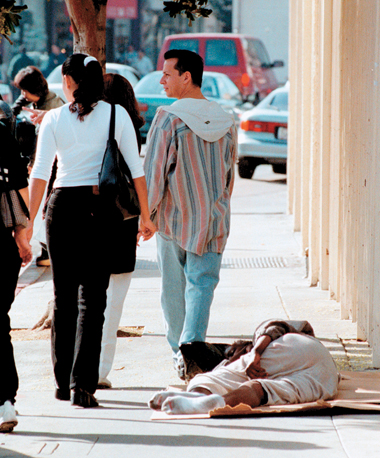

A man lies ill on the sidewalk in full view of hundreds of passersby, all of whom fail to stop and ask if he needs help. A woman is brutally beaten in front of witnesses who fail to come to her aid or even to call the police. How can such incidents occur?

In many experiments, social psychologists have found that a person is much more likely to help in an emergency if he or she is the only witness than if other witnesses are also present (Latané & Nida, 1981). In one experiment, for example, college students filling out a questionnaire were interrupted by the sound of the researcher, behind a screen, falling and crying out, “Oh … my foot … I … can’t move it; oh … my ankle … I can’t get this thing off me” (Latané & Rodin, 1969). In some cases the student was alone, and in other cases two students sat together filling out questionnaires. The remarkable result was that 70 percent of those who were alone went to the aid of the researcher, but only 20 percent of those who were in pairs did so. Apparently an accident victim is better off with just one potential helper present than with two! Why? Part of the answer probably has to do with diffusion of responsibility. The more people present, the less any one person feels it is his or her responsibility to help (Schwartz & Gottlieb, 1980). But conformity also seems to contribute.

549

12

How can the failure of multiple bystanders to help a person in need be explained in terms of informational and normative influences?

If you are the only witness to an incident, you decide whether it is an emergency or not, and whether you can help or not, on the basis of your assessment of the victim’s situation. But if other witnesses are present, you look also at them. You wait just a bit to see what they are going to do, and chances are you find that they do nothing (because they are waiting to see what you are going to do). Their inaction is a source of information that may lead you to question your initial judgment: Maybe this is not an emergency, or if it is, maybe nothing can be done. Their inaction also establishes an implicit social norm. If you spring into action, you might look foolish to the others, who seem so complacent. Thus, each person’s inaction can promote inaction in others through both informational and normative influences.

These interpretations are supported by experiments showing that the inhibiting effect of others’ presence is reduced or abolished by circumstances that alter the informational and normative influences of the other bystanders. If the bystanders indicate, by voice or facial expressions, that they do interpret the situation as an emergency, then their presence has a much smaller or no inhibiting effect on the target person’s likelihood of helping (Bickman, 1972). If the bystanders know one another well—and thus have less need to manage their impressions in front of one another, or know that each shares a norm of helping—they are more likely to help than if they don’t know one another well (Rutkowski et al., 1983; Schwartz & Gottlieb, 1980).

Emotional Contagion as a Force for Group Cohesion

A social group is not just a collection of individuals. It is a unified collection. People in a social group behave, in many ways, more like one another than the same people would if they were not in a group. They tend automatically to mimic one another’s postures, mannerisms, and styles of speech, and this imitation contributes to their sense of rapport (Lakin & Chartrand, 2003; van Baaren et al., 2004). They also tend to take on the same emotions.

13

What is the value, for group life, of the spread of sadness, anger, fear, and laughter from person to person? How might emotional contagion figure into the rise of a group leader?

As noted in Chapter 3, people everywhere express emotions in relatively similar ways. Such facial expressions help members of a group know how to interact with one another. By seeing others’ emotional expressions, group members know who needs help, who should be avoided, and who is most approachable at the moment for help. In addition, people tend automatically to adopt the emotions that they perceive in those around them, and this helps the group to function as a unit (Hatfield et al., 1994; Wild et al., 2001). Sadness in one person tends to induce sadness in others nearby, and that is part of the mechanism of empathy by which others become motivated to help the one in distress; the early appearance of empathy in children is discussed in Chapter 12. Anger expressed in the presence of potential allies may lead to shared anger that promotes their recruitment into a common cause. Likewise, fear in one person tends to induce fear in others nearby, placing them all in a state of heightened vigilance and thereby adding a measure of protection for the whole group.

One of the most contagious of all emotional signals is laughter, as evidenced by the regularity of mutual laughter in everyday interactions and the effectiveness of laugh tracks (often added to recorded comedy) in inducing laughter in audiences (Provine, 1996, 2004). The easy spread of laughter apparently helps put a group into a shared mood of playfulness, which reduces the chance that one person will be offended by the remarks or actions of another.

550

Researchers have found that the spread of emotions can occur completely unconsciously. Facial expressions of emotions flashed on a screen too quickly for conscious recognition can cause subjects to express the same emotion on their own faces and/or to experience brief changes in feeling compatible with that emotion (Dimberg et al., 2000; Ruys & Stapel, 2008).

Political leaders often achieve their status at least partly through their ability to manipulate others’ emotions, and their own emotional expressions are part of that process. Former U.S. presidents Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton were both known as “great communicators,” and much of their communication occurred through their persuasive facial expressions. In a research study conducted shortly after Reagan was elected president, university students watched film clips of Reagan expressing happiness, anger, or fear as he spoke to the American public about events that faced the nation (McHugo et al., 1985). In some cases the sound track was kept on, in others it was turned off, and in all cases the students’ own emotional reactions were recorded by measuring their heart rates, their perspiration, and the movements of particular facial muscles. Regardless of whether they claimed to be his supporters or opponents, and regardless of whether they could or could not hear what he was saying, the students’ bodily changes indicated that they were responding to Reagan’s performance with emotions similar to those he was displaying.

Social Pressure in Group Discussions

When people get together to discuss an idea or make a decision, their explicit goal usually is to share information. But whether they want to or not, group members also influence one another through normative social pressure. Such pressure can occur whenever one person expresses an opinion or takes a position on an issue in front of another: Are you with me or against me? It feels good to be with, uncomfortable to be against. There is unstated pressure to agree.

Group Discussion Can Make Attitudes More Extreme

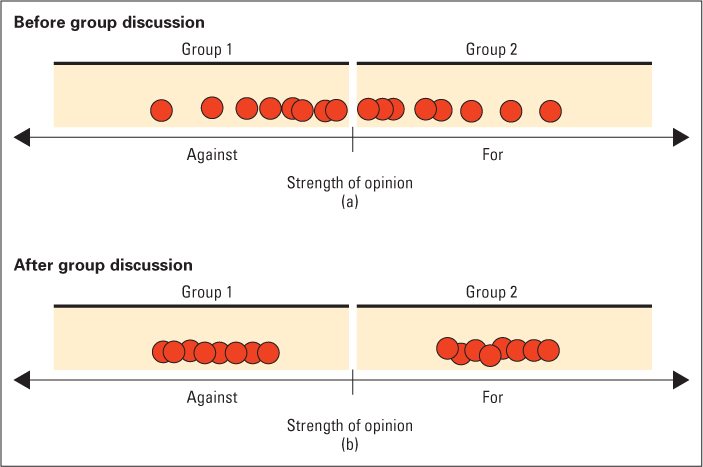

When a group is evenly split on an issue, the result is often a compromise (Burnstein & Vinokur, 1977). Each side partially convinces the other, so the majority leave the room with a more moderate view on the issue than they had when they entered. However, if the group is not evenly split—if all or a large majority of the members argue on the same side of the issue—discussion typically pushes that majority toward a more extreme view in the same direction as their initial view. This phenomenon is called group polarization.

14

What are some experiments that have demonstrated group polarization?

Group polarization has been demonstrated in many experiments, with a wide variety of problems or issues for discussion. In one experiment, mock juries evaluated traffic-violation cases that had been constructed to produce either high or low initial judgments of guilt. After group discussion, the jurors rated the high-guilt cases as indicating even higher levels of guilt, and the low-guilt cases as indicating even lower levels of guilt, than they had before the discussion (Myers & Kaplan, 1976). In other experiments, researchers divided people into groups on the basis of their initial views on a controversial issue and found that discussions held separately by each group widened the gaps between the groups (see Figure 14.6). In one experiment, for example, discussion caused groups favoring a strengthening of the military to favor it even more strongly and groups favoring a paring down of the military to favor that more strongly (Minix, 1976; Semmel, 1976).

Group polarization can have socially serious consequences. When students whose political views are barely to the right of center get together to form a Young Conservatives club, their views are likely to shift further toward the right. Similarly, a Young Liberals club is likely to shift to the left. Prisoners who enter prison with little respect for the law and spend their time talking with other prisoners who share that view are likely to leave prison with even less respect for the law than they had before. Systematic studies of naturally occurring social groups suggest that such shifts are indeed quite common (Sunstein, 2003).

551

What Causes Group Polarization?

15

How might group polarization be explained in terms of (a) informational and (b) normative influences?

Just as social psychologists characterize social influence as either informational or normative, they have also proposed these two classes of explanations for group polarization. Informational explanations focus on the pooling of arguments that occurs during group discussion. People vigorously put forth arguments favoring the side toward which they lean and tend to withhold arguments that favor the other side. As a result, the group members hear a disproportionate amount of information on the side of their initial leaning, which may persuade them to lean even further in that direction (Kaplan, 1987; Vinokur & Burnstein, 1974). Moreover, simply hearing others repeat one’s own arguments in the course of discussion can have a validating effect. People become more convinced of the soundness of their own logic and the truth of the “facts” they know when they hear the logic and facts repeated by another person (Brauer et al., 1995).

Normative explanations attribute group polarization to people’s concerns about being approved of by other group members. One might expect normative influences to cause opinions within a group to become more similar to one another, but not more extreme. In fact, as illustrated in Figure 14.6, they do become more similar as well as, on average, more extreme.

Several normative hypotheses have been offered to explain why opinions within a like-minded group become more extreme. According to one, which we can call the one-upmanship hypothesis, group members vie with one another to become the most vigorous supporter of the position that most people favor, and this competition pushes the group as a whole toward an increasingly extreme position (Levinger & Schneider, 1969; Myers, 1982). According to another hypothesis, which we can call the group differentiation hypothesis, people who see themselves as a group often exaggerate their shared group opinions as a way of clearly distinguishing themselves from other groups (Hogg et al., 1990; Keltner & Robinson, 1996). The Young Liberals become more liberal to show clearly that they are not like those hard-hearted conservatives in the other club, and the Young Conservatives become more conservative to show that they are not like those soft-headed liberals.

552

As is so often the case in psychology, the hypotheses developed by different researchers are all probably valid, to differing degrees, depending on conditions. Group polarization in most instances probably results from a combination of normative and informational influences.

Conditions That Lead to Good or Bad Group Decisions

Decisions made by groups are sometimes better and sometimes worse than decisions made by individuals working alone. To the degree that the group decision arises from the sharing of the best available evidence and logic, it is likely to be better (Surowiecki, 2004b). To the degree that it arises from shared misinformation, selective withholding of arguments on the less-favored side, and participants’ attempts to please or impress one another rather than to arrive at the best decision, the group decision is likely to be worse than the decision most group members would have made alone.

16

How did Janis explain some White House policy blunders with his groupthink theory? What can groups do to reduce the risk of groupthink?

In a now-classic book titled Groupthink, Irving Janis (1982) analyzed some of the most misguided policy decisions made in the U.S. White House. Among them were the decisions to sponsor the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba in 1961 (an invasion that failed disastrously); to escalate the Vietnam War during the late 1960s; and to cover up the Watergate burglary in the early 1970s. Janis contends that each of these decisions came about because a tightly knit clique of presidential advisers, whose principal concerns were upholding group unity and pleasing their leader (Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon, respectively), failed to examine critically the choice that their leader seemed to favor and instead devoted their energy to defending that choice and suppressing criticisms of it.

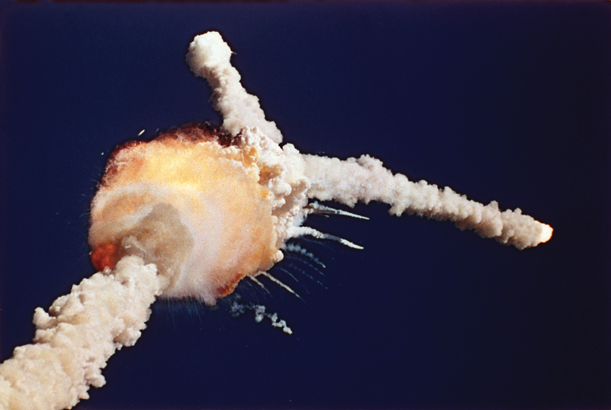

To refer to such processes, Janis coined the term groupthink, which he defined as “a mode of thinking that people engage in when they are deeply involved in a cohesive ingroup, when the members’ striving for unanimity overrides their motivation to realistically appraise alternative courses of action.” More recently, many other ill-advised decisions have been attributed to groupthink, including the decision by NASA to launch the U.S. space shuttle Challenger in below-freezing weather, which resulted in the explosion of the vehicle and the deaths of seven crew members, including a high school social studies teacher (Moorhead et al., 1991); the endorsements by corporate boards of shady accounting practices, which led to the downfalls of Enron and several other large corporations (Postmes et al., 2001; Surowiecki, 2004a); and various decisions by the G. W. Bush administration concerning the invasion and occupation of Iraq (Houghton, 2008).

A number of experiments have aimed at understanding the conditions that promote or prevent groupthink. Overall, the results suggest that the ability of groups to solve problems and make effective decisions is improved if (a) the leaders refrain from advocating a view themselves and instead encourage group members to present their own views and challenge one another (Leana, 1985; Neck & Moorhead, 1995), and (b) the groups focus on the problem to be solved rather than on developing group cohesion (Mullen et al., 1994; Quinn & Schlenker, 2002). It is hard to learn this lesson, but a group that values the dissenter rather than ostracizes that person is a group that has the potential to make fully informed, rational decisions.

553

SECTION REVIEW

The opinions and examples of others can have strong effects on what we say and do.

Conformity Experiments

- Asch found that subjects often stated agreement to the majority view in judging the lengths of lines, even if it meant contradicting the evidence of their own eyes.

- Social influence leading to conformity can be normative (motivated by a desire to be accepted) or informational (motivated by a desire to be correct).

- Even a single dissenting opinion can sharply reduce the tendency of others to conform.

Helpful and Harmful Norms

- According to the broken windows theory of crime, cues suggesting that disrespect for the law is normal can lead to an escalation in crime.

- Public-service messages can be made more effective if they portray the undesirable behavior as nonnormative.

- The more bystanders present at an emergency, the less likely any of them are to help. This may result from both informational and normative influences.

- Emotional contagion acts to unite the members of a group, coordinating their actions and promoting bonds of attachment. Successful leaders are often particularly good at expressing emotions in ways that lead others to share those emotions.

Social Pressure Within Groups

- When most or all the people in a group initially agree, group discussion typically moves them toward a more extreme version of their initial view—a phenomenon called group polarization.

- Both informational and normative influences may contribute to group polarization.

- Groupthink occurs when group members are more concerned with group cohesion and unanimity than with genuine appraisal of various approaches to a problem.