15.3 Personality as Mental Processes I: Psychodynamic and Humanistic Views

Trait theories, such as the five-factor model, are useful as general schemes for describing human psychological differences and for thinking about possible functions of those differences. Such theories have little to say, however, about the internal mental processes that lead people to behave in particular ways. The rest of this chapter is devoted to ideas about the mental underpinnings of personality.

We begin by examining two very general, classic theoretical perspectives on personality: the psychodynamic and humanistic perspectives. These two perspectives derive largely from the observations and speculations of clinical psychologists, who were attempting to make sense of the symptoms and statements of their clients or patients. These two perspectives also provide much of the basis for the general public’s understanding of psychology.

595

Elements of the Psychodynamic Perspective

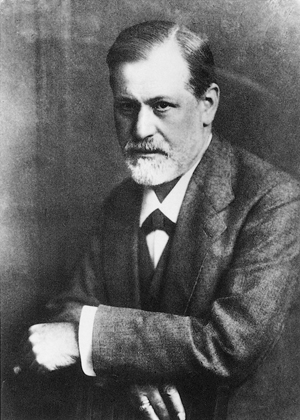

The pioneer of clinical psychology, and of the clinical approach to understanding personality, was Sigmund Freud (1856–1939). Freud was a physician who specialized in neurology and, from 1886 on, worked with patients at his private office in Vienna. He found that many people who came to him had no detectable medical problems; their suffering seemed to derive from their memories, especially their memories of disturbing events in their childhoods. In many cases, they could not recall such memories consciously, but clues in their behavior led Freud to believe that disturbing memories were present nevertheless, buried in what he referred to as the unconscious mind. From this insight, Freud developed a method of treatment in which his patients would talk freely about themselves and he would analyze what they said in order to uncover buried memories and hidden emotions and motives. The goal was to make the patient conscious of his or her unconscious memories, motives, and emotions so that the patient’s conscious mind could work out ways of dealing with them.

19

What characteristics of the mind underlie personality differences, according to the psychodynamic perspective?

Freud coined the term psychoanalysis to refer both to his method of treatment (discussed in Chapter 17) and to his theory of personality. Freud’s psychoanalytic theory was the first of what today are called psychodynamic theories—personality theories that emphasize the interplay of mental forces (the word dynamic refers to energy or force and psycho refers to mind). Two guiding premises of psychodynamic theories are that (a) people are often unconscious of their motives and (b) processes called defense mechanisms work within the mind to keep unacceptable or anxiety-producing motives and thoughts out of consciousness. According to psychodynamic theories, personality differences lie in variations in people’s unconscious motives, in how those motives are manifested, and in the ways that people defend themselves from anxiety.

Freud also emphasized that personality developed following a stage theory (oral, anal, phallic, latency, and genital stages). Freud proposed that the sex drive is a primary instinct, expressed at all stages of life. The main source of pleasure satisfaction, or tension reduction, is centered on specific bodily zones, called erogenous zones. (We should note that Freud often used the word “sexuality” in a broader sense than laypeople do; in his usage it was often a synonym for “looking for pleasure.”) These zones change through the course of development, with erogenous centers shifting from the oral to the anal area over the course of early childhood, and then eventually to the genital area. According to Freud, how parents deal with their children’s sexual (or pleasure-seeking) impulses has significant consequences for their later development. Although Freud’s stage theory is one of the best known in psychology, there is little research evidence supporting it, and few personality or developmental psychologists take his stage theory seriously; for that reason we will not discuss it further here.

The Concept of Unconscious Motivation

Freud proposed that the main causes of behavior lie deeply buried in the unconscious mind—that is, in the part of the mind that affects the individual’s conscious thought and action but is not itself open to conscious inspection. The reasons people give to explain their behavior often are not the true causes. To illustrate this idea, Freud (1912/1932) drew an analogy between everyday behavior and the phenomenon of posthypnotic suggestion.

20

How is the concept of unconscious motivation illustrated by posthypnotic suggestion?

In a demonstration of posthypnotic suggestion, a person is hypnotized and given an instruction such as “When you awake, you will not remember what happened during hypnosis. However, when the clock chimes, you will walk across the room, pick up the umbrella lying there, and open it.” When awakened, the subject appears to behave in a perfectly normal, self-directed way until the clock chimes. At this signal the subject consciously senses an irresistible impulse to perform the commanded action, and consciously performs it, but has no conscious memory of the origin of the impulse (the hypnotist’s command). If asked why he or she is opening the umbrella, the subject may come up with a plausible though clearly false reason, such as “I thought I should test it because it may rain later.” According to Freud, the real reasons behind our everyday actions are likewise hidden in our unconscious minds, and our conscious reasons are cover-ups, plausible but false rationalizations that we believe to be true.

596

Freud believed that to understand his patients’ actions, problems, and personalities, he had to learn about the contents of their unconscious minds. But how could he do that when the unconscious, by definition, consists only of information that the patient cannot talk about? He claimed that he could do it by analyzing certain aspects of their speech and other observable behavior to draw inferences about their unconscious motives. This is where the term psychoanalysis comes from. His technique was to sift the patient’s behavior for clues to the unconscious. Like a detective, he collected clues and tried to piece them together into a coherent story about the unconscious causes of the person’s conscious thoughts and actions.

Because the conscious mind always attempts to act in ways that are consistent with conventional logic, Freud reasoned that the elements of thought and behavior that are least logical would provide the best clues to the unconscious. They would represent elements of the unconscious mind that leaked out relatively unmodified by consciousness. Freud therefore paid particular attention to his patients’ slips of the tongue and other mistakes as clues to the unconscious. He also asked them to describe their dreams and to report in uncensored fashion whatever thoughts came to mind in response to particular words or phrases. These methods are described more fully, with examples, in Chapter 17.

Sex and Aggression as Motivating Forces in Freud’s Theory

21

Why did Freud consider sex and aggression to be especially significant drives in personality formation?

Unlike most modern psychologists, Freud considered drives to be analogous to physical forms of energy that build up over time and must somehow be released. To live peaceably in society (especially in the Victorian society that Freud grew up in), people must often inhibit direct expressions of the sexual and aggressive drives, so these are the drives that are most likely to build up and exert themselves in indirect ways. Freud concluded from his observations that much of human behavior consists of disguised manifestations of sex and aggression and that personality differences lie in the different ways that people disguise and channel these drives. Over time, Freud (1933/1964) came to define these drives increasingly broadly. He considered the sex drive to be the main pleasure-seeking and life-seeking drive and the aggressive drive to be the force that lies behind all sorts of destructive actions, including actions that harm oneself.

Social Drives as Motives in Other Psychodynamic Theories

Freud viewed people as basically asocial, forced to live in societies more by necessity than by desire, and whose social interactions derive primarily from sex, aggression, and displaced forms of these drives. In contrast, most psychody-namic theorists since Freud’s time have viewed people as inherently social beings whose motives for interacting with others extend well beyond sex and aggression.

For example, Alfred Adler developed a psychodynamic theory that centers on people’s drive to feel competent. Adler (1930) contended that everyone begins life with a feeling of inferiority, which stems from the helpless and dependent nature of early childhood, and that the manner in which people learn to cope with or to overcome this feeling provides the basis for their lifelong personalities. According to Adler, people who become overwhelmed by a sense of inferiority will develop either an inferiority complex, and go through life acting incompetent and dependent, or a superiority complex, and go through life trying to prove they are better than others as a means of masking their inferiority.

597

Perhaps the most “social” of Freud’s followers was Erik Erikson (1950, 1968), who proposed a psychosocial theory of development. Erikson believed in the psycho-sexual stages postulated by Freud (oral, anal, phallic, latency, and genital), as well as the three-part structure of the mind (id, ego, and superego) and the importance of the unconscious. However, unlike Freud, Erikson emphasized the role of society in shaping personality. Other people, and society in general, place demands on people as they develop, and how children (and later adults) handle these demands affects their personalities. In addition, Erikson believed that important developmental milestones extended beyond childhood into adulthood and old age.

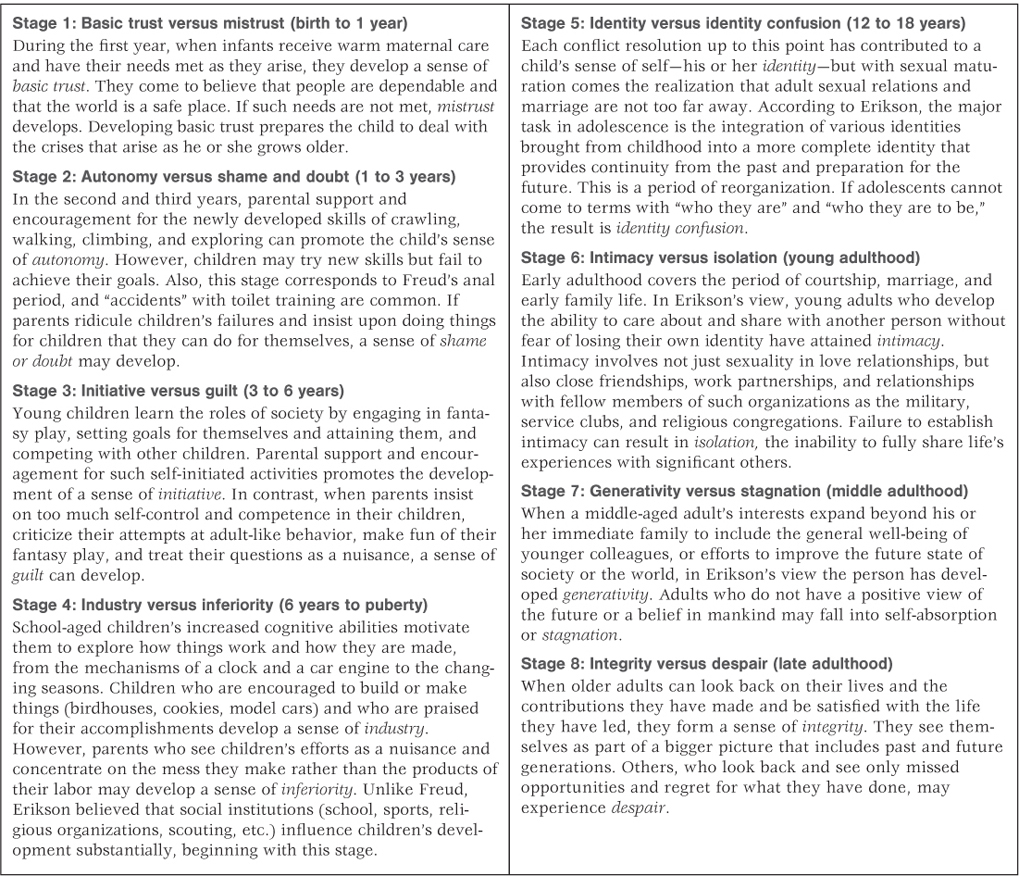

Erikson proposed eight stages of psychosocial development, beginning at birth and continuing through the life span. Erikson believed that people face conflicts, or crises, at each of these stages in their relationships with other people, and how they deal with the crisis at one stage influences how they will deal with crises at the next and following stages. Table 15.4 summarizes Erikson’s eight stages of development.

Erikson’s psychosocial stages of development with approximate ages

598

In all psychodynamic theories, including Freud’s, the first few years of life are especially crucial in forming the personality. One’s earliest attempts to satisfy drives result in positive or negative responses from others that, taken together, have lifelong effects on how those drives are subsequently manifested.

The Idea That the Mind Defends Itself Against Anxiety

A central idea in all psychodynamic theories is that mental processes of self-deception, referred to as defense mechanisms, operate to reduce one’s consciousness of wishes, memories, and other thoughts that would threaten one’s self-esteem or in other ways provoke a strong sense of insecurity or anxiety. The theory of defense mechanisms was most thoroughly developed by Anna Freud (1936/1946), Sigmund’s daughter, who was also a prominent psychoanalyst. Some examples of defense mechanisms are repression, displacement, reaction formation, projection, and rationalization.

22

How do repression, displacement, reaction formation, projection, and rationalization each serve to defend against anxiety?

Repression (discussed more fully in the next section) is the process by which anxiety-producing thoughts are pushed out or kept out of the conscious mind. In Freud’s theory, repression provides the basis for most of the other defense mechanisms. Freud visualized repression as a damming up of mental energy. Just as water will leak through any crack in a dam, repressed wishes and memories will leak through the barriers separating the unconscious mind from the conscious mind. When such thoughts leak through, however, the mind can still defend itself by distorting the ideas in ways that make them less threatening. The other defense mechanisms are the various means by which we create such distortions.

Displacement occurs when an unconscious wish or drive that would be unacceptable to the conscious mind is redirected toward a more acceptable alternative. For example, a child long past infancy may still have a desire to suck at the mother’s breast—a desire that is now threatening and repressed because it violates the child’s conscious understanding of what is proper and possible. The desire might be displaced toward sucking on a lollipop, an action that is symbolically equivalent to the original desire but more acceptable and realistic.

In some cases, displacement may direct one’s energies toward activities that are particularly valued by society, such as artistic, scientific, or humanitarian endeavors. In these cases displacement is referred to as sublimation. A highly aggressive person might perform valuable service in a competitive profession, such as being a trial lawyer, as sublimation of the drive to beat others physically. As another example, Freud (1910/1947) suggested that Leonardo da Vinci’s fascination with painting Madonnas was a sublimation of his desire for his mother, which had been frustrated by his separation from her.

Reaction formation is the conversion of a frightening wish into its safer opposite. For example, a young woman who unconsciously hates her mother and wishes her dead may consciously experience these feelings as intense love for her mother and strong concern for her safety. Psychodynamic theorists have long speculated that homophobia—the irrational fear and hatred of homosexuals—may often stem from reaction formation. People who have a tendency toward homosexuality, but fear it, may protect themselves from recognizing it by vigorously separating themselves from homosexuals (West, 1977). In a study supporting that explanation, men who scored highly homophobic on a questionnaire were subsequently found, through direct physical measurement, to show more penile erection while watching a male homosexual video than did other men, even though they denied experiencing any sexual arousal while watching the video (Adams et al., 1996).

Projection occurs when a person consciously experiences an unconscious drive or wish as though it were someone else’s. A person with intense, unconscious anger may project that anger onto her friend—she may feel that it is her friend, not she, who is angry. In an early study of projection conducted at college fraternity houses, Robert Sears (1936) found that men who were rated by their fraternity brothers as extreme on a particular characteristic, such as stinginess, but who denied that trait in themselves tended to rate others as particularly high on that same characteristic.

599

Rationalization is the use of conscious reasoning to explain away anxiety-provoking thoughts or feelings. A man who cannot face his own sadistic tendencies may rationalize the beatings he gives his children by convincing himself that children need to be beaten and that he is only carrying out his fatherly duty. Psychodynamic theories encourage us to be wary of conscious logic, since it often serves to mask true feelings and motives. (For discussion of the left-hemisphere interpreter, which seems to be the source of rationalization, look back at Chapter 5, p. 183.)

Defensive Styles as Dimensions of Personality

Of all of Freud’s big ideas about the mind, his concept of psychological defense has had the most lasting appeal in psychology and has generated the most research (Cramer, 2000). Some of the cognitive biases discussed in Chapter 13, by which people enhance their own perceptions of themselves and rationalize their own morally questionable actions, can be understood as defense mechanisms. These biased ways of thinking reduce anxiety by bolstering people’s images of themselves as highly competent and ethical.

Much modern research on defense mechanisms focuses on individual differences in defensive styles. Some people habitually employ certain defenses as their routine modes of dealing with stressful situations in their lives, such that the defense mechanism can be thought of as a dimension of their personality. The most fully researched defensive style is that referred to as repressive coping.

Repressive Coping as a Personality Style

Freud’s theory of repression centered on the idea that people often repress memories of traumatic or highly disturbing events so fully that they can be recalled only through psychotherapy, which uncovers them. Today this idea is still highly controversial. In cases where people claim to have recovered repressed memories of past events it is usually hard to verify that the events actually occurred (McNally, 2003). As described in Chapter 9, people often construct false memories of the past, based on cues in the present, and then cannot distinguish those memories from true memories. Most people who have suffered truly traumatic experiences wish they could forget them but cannot (Goodman et al., 2003). Repression of traumatic memories may well occur in some cases, but so far this has been difficult to document as a general phenomenon.

600

23

What evidence exists that some people regularly repress anxious feelings? In general, how do such “repressors” differ from others in their reactions to stressful situations?

In contrast, there is ample evidence that many people regularly repress the emotional feelings that accompany disturbing events in their lives. They are able to recall and describe the events, but they claim that such memories do not make them anxious or otherwise disturb them. Personality researchers refer to these people as repressors. For research purposes, repressors are identified by their scores on standardized questionnaires for assessing anxiety and defensiveness. They are people who report experiencing very little anxiety, but who answer other questions in ways that seem highly defensive (Weinberger, 1990). Their questionnaire responses indicate that they have an especially strong need to view themselves in a very favorable light; they do not admit to the foibles that characterize essentially all normal people.

Many research studies have compared repressors, identified in this way, with nonrepressors in their reactions to moderately distressing situations in the laboratory. For example, subjects might be asked to complete sentences that contain sexual or aggressive themes, or to describe their least-desirable traits, or to recall fearful experiences that happened to them in the past, or to imagine some unhappy event that could afflict them in the future. The general finding is that repressors report much less psychological distress in these situations than do nonrepressors; but, by physiological indices—such as heart rate, muscle tension, and perspiration—they manifest more distress than do nonrepressors (Derakshan et al., 2007; Weinberger, 1990). Research indicates that they are not lying when they say that they experience little anxiety; they apparently really believe what they are saying. Somehow they have banished anxious thoughts and feelings from their conscious minds, but have not banished the bodily reactions of anxiety.

In other experiments, repressors reported less anxiety or other unpleasant emotions in daily diaries, recalled fewer negative childhood experiences, and were less likely to notice consciously or remember emotion-arousing words or phrases presented during an experiment than was the case for nonrepressors (Bonanno et al., 1991; Cutler et al., 1996; Davis & Schwartz, 1987; Fujiwara et al., 2008). They apparently avoid experiences of anxiety by diverting their conscious attention away from anxiety-arousing stimuli and by dwelling on pleasant rather than unpleasant thoughts.

24

What benefit and harm might accrue from the repressive style of coping?

A good deal of research has centered on the possible benefits and harm of the repressive style of coping. The repressive style may often originate, and be most helpful, at a time when the person is coping with a seriously disturbing life event. For example, this style is common among adolescent cancer survivors, and it seems to help them to maintain a remarkably positive outlook on life (Erickson et al., 2008). Other research indicates that the repressive style helps people who have had heart attacks, or who have lost loved ones to suicide, cope psychologically (Ginzburg et al., 2002; Parker & McNally, 2008). Laboratory studies suggest that repression may help people in these situations by preserving their conscious minds—their working memories—for rational planning and problem solving. As described in Chapter 14, anxious thoughts occupy space in working memory and thereby interfere with the person’s ability to solve problems. Repressors are apparently much less affected by this than are the rest of us (Derakshan & Eysenck, 1998; Parker & McNally, 2008). They continue to function effectively, at work and elsewhere, despite events that would traumatize others.

On the other side of the coin, however, is evidence that repressors may develop more health problems and experience more chronic pain than do nonrepressors (Burns, 2000; Schwartz, 1990). This is consistent with the idea that they experience stress physically rather than as conscious emotion. Repressors may be promoting their cognitive functioning at some cost to their bodies. Like most personality dimensions, repressive coping has benefits and costs; the overall balance between the two depends on the environmental conditions to which the person must adapt.

601

Distinction Between Mature and Immature Defensive Styles

Other research on defensive styles has focused on the idea that some defenses are more conducive to a person’s long-term well-being than are others. The most ambitious and famous such study was begun in the 1930s, with male sophomores at Harvard University as subjects.

Each year until 1955, and less often after that, the Harvard men filled out an extensive questionnaire concerning such issues as their work, ambitions, social relationships, emotions, and health. Nearly 30 years after the study began, when the men were in their late 40s, a research team led by George Vaillant (1995) interviewed in depth 95 of these men, randomly selected. By systematically analyzing the content and the style of their responses in the interview and on the previous questionnaires, the researchers rated the extent to which each man used specific defense mechanisms.

25

What relationships did Vaillant find between defensive styles and measures of life satisfaction?

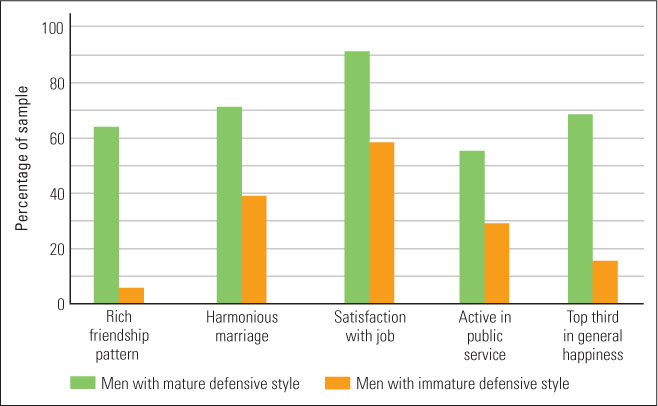

Vaillant divided the various defense mechanisms into categories according to his judgment of the degree to which they would seem to promote either ineffective or effective behavior. Immature defenses were those presumed to distort reality the most and to lead to the most ineffective actions. Projection was included in this category. Intermediate defenses (referred to by Vaillant as “neurotic defenses”), including repression and reaction formation, were presumed to involve less distortion of reality and to lead to somewhat more effective coping. Mature defenses were presumed to involve the least distortion of reality and to lead to the most adaptive behaviors. One of the most common of the mature defenses was suppression, which involves the conscious avoidance of negative thinking. Suppression differs from repression in that the person has more conscious control over the decision to think about, or not think about, the distressing experience. Another defense in the mature category was humor, which, according to Freud and other psychodynamic theorists, reduces fear by making fun of feared ideas.

Consistent with Vaillant’s expectations, the men who used the most mature defenses were the most successful on all measures of ability to love and work (Freud’s criteria for mature adulthood). They were also, by their own reports, the happiest. Figure 15.8 depicts some of the comparisons between the men who used mainly mature defenses and those who used mainly immature defenses. Vaillant (1995) also found, not surprisingly, that as the Harvard men matured—from age 19 into their 40s—the average maturity of their defenses increased. Immature defenses such as projection declined, and mature defenses such as suppression and humor increased.

(Based on data from Vaillant, 1977.)

602

In subsequent research, using more diverse groups of subjects, including women as well as men, Vaillant and others found similar results (Cramer, 2008; Vaillant, 2002; Vaillant & Vaillant, 1992). As they grow older, from adolescence on, people rely less on defenses that deny or distort reality and more on defenses that allow them to accept reality. The use of mature rather than immature defenses correlates positively with measures of life satisfaction and success. Such correlations do not prove that mature defenses cause successful coping, but they do at least show that the two tend to go together.

The Humanistic Perspective: The Self and Life’s Meanings

26

How, in general, do humanistic theories differ from psychodynamic theories?

Humanistic theories of personality arose, in the mid-twentieth century, partly in reaction to the then-dominant psychodynamic theories. While psychodynamic theories emphasize unconscious motivation and defenses, humanistic theories emphasize people’s conscious understanding of themselves and their capacity to choose their own paths to fulfillment. They are called humanistic because they center on an aspect of human nature that seems to distinguish us clearly from other animals—our tendency to create belief systems, to develop meaningful stories about ourselves and our world, and to govern our lives in accordance with those stories.

Phenomenology is the study of conscious perceptions and understandings, and humanistic theorists use the term phenomenological reality to refer to each person’s conscious understanding of his or her world. Humanistic theorists commonly claim that one’s phenomenological reality is one’s real world; it provides the basis for the person’s contentment or lack of contentment and for the meaning that he or she finds in life. In the words of one of the leaders of humanistic psychology, Carl Rogers (1980): “The only reality you can possibly know is the world as you perceive and experience it…. And the only certainty is that those perceived realities are different. There are as many ‘real worlds’ as there are people.”

Being One’s Self; Making One’s Own Decisions

27

What human drive, or goal, characterizes healthy development in Rogers’s self theory?

According to most humanistic theories, a central aspect of one’s phenomenological reality is the self-concept, the person’s understanding of who he or she is. Rogers referred to his own version of humanistic theory as self theory. He claimed that at first he avoided the construct of self because it seemed unscientific, but was forced to consider it through listening to his clients in therapy sessions. Person after person would say, in effect, “I feel I am not being my real self”; “I wouldn’t want anyone to know the real me”; or “I wonder who I am.” From such statements, Rogers (1959) gradually came to believe that a concept of self is a crucial part of a person’s phenomenological reality and that a common goal of people is to “discover their real selves” and “become their real selves.”

According to Rogers, people often are diverted from becoming themselves by the demands and judgments placed on them by other people, particularly by authority figures such as parents and teachers. To be oneself, according to Rogers, is to live life according to one’s own wishes rather than someone else’s. Thus, an important dimension of individual difference, in Rogers’s theory, has to do with the degree to which a person feels in charge of his or her own life.

As would be predicted by Rogers’s theory, researchers have found that people who feel as if a decision is fully their own, made freely by themselves, are more likely to follow through and act on it effectively than are people who feel that they are doing something because of social pressure or because an authority figure thinks they should do it. Those who think and talk about their intention to lose weight, stop smoking, exercise more, or take prescribed medicines on schedule as “following the doctor’s orders” are less likely to succeed at such goals than are those who think and talk about the decision as their own (Ryan & Deci, 2000; Williams et al., 1995, 1996; Wilson et al., 2003). Employees who feel that their job is their own choice, and that they are in charge of how they do the job, are happier and perform better than otherwise similar employees who feel that their work is dictated by other people or by necessity (Gagné & Deci, 2005). Other research—conducted in such diverse countries as Canada, Brazil, Russia, South Korea, Japan, and Turkey—has shown that people who feel that they are following their own desires are happier and more productive than those who feel that they are responding to social pressures (Chirkov et al., 2003, 2005; Ryan & Deci, 2006). In different cultures, people tend to have different values and to choose different activities, but in each culture those who see those choices as their own claim to be most satisfied with their lives.

603

Self-Actualization and Maslow’s Hierarchy of Human Needs

Humanistic theorists use the term self-actualization to refer to the process of becoming one’s full self—that is, of realizing one’s dreams and capabilities. The specific route to self-actualization will vary from person to person and from time to time within a person’s lifetime, but for each individual the route must be self-chosen.

28

What is Maslow’s theory about the relationship among various human needs? How might the theory be reconciled with an evolutionary perspective?

Rogers (1963, 1977) often compared self-actualization in humans to physical growth in plants. A tree growing on a cliff by the sea must battle against the wind and saltwater and does not grow as well as it would in a more favorable setting, yet its inner potential continues to operate and it grows as well as it can under the circumstances. Nobody can tell the tree how to grow; its growth potential lies within itself. Humanistic theorists hold that full growth, full actualization, requires a fertile environment, but that the direction of actualization and the ways of using the environment must come from within the organism. In the course of evolution, organisms have acquired the capacity to use the environment in ways that maximize growth. In humans, the capacity to make free, conscious choices that promote positive psychological growth is the actualizing tendency. To grow best, individuals must be permitted to make those choices and must trust themselves to do so.

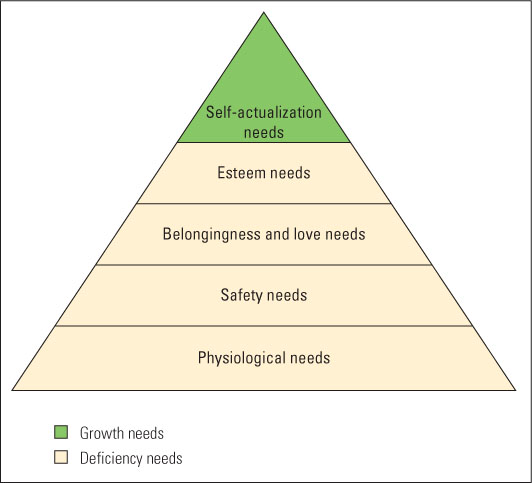

Another pioneer of humanistic psychology, Abraham Maslow (1970), suggested that to self-actualize one must satisfy five sets of needs that can be arranged in a hierarchy (see Figure 15.9). From bottom to top, they are (1) physiological needs (the minimal essentials for life, such as food and water); (2) safety needs (protection from dangers in the environment); (3) attachment needs (acceptance and love); (4) esteem needs (competence, respect from others and the self); and (5) self-actualization needs. In Maslow’s view, the self-actualization needs encompass the needs for self-expression, creativity, and “a sense of connectedness with the broader universe.” Maslow argued that a person can focus on higher needs only if lower ones, which are more immediately linked to survival, are sufficiently satisfied so that they do not claim the person’s full attention and energy.

Maslow’s needs hierarchy makes some sense from an evolutionary perspective. The physiological and safety needs are most basic in that they are most immediately linked to survival. If one is starving or dehydrated, or if a tiger is charging, then survival depends immediately upon devoting one’s full resources to solving that problem. The social needs for acceptance, love, and esteem are also linked to survival, though not in quite as direct and immediate a fashion. We need to maintain good social relationships with others to ensure their future cooperation in meeting our physiological and safety needs and in helping us reproduce. Continuing in this line of thought, we would suggest that the self-actualization needs are best construed evolutionarily as self-educative needs. Playing, exploring, and creating can lead to the acquisition of skills and knowledge that help one later in such endeavors as obtaining food, fending off predators, attracting mates, and securing the goodwill and protection of the community. From this perspective, self-actualization is not in any ultimate sense “higher” than the other needs but is part of the long-term way of satisfying those needs.

604

SECTION REVIEW

Psychodynamic and humanistic personality theories focus on mental processes.

The Psychodynamic Perspective

- Freud, whose psychoanalytic views originated this perspective, believed that the real causes of behavior lie in the unconscious mind, with sexual and aggressive motives being especially important.

- Other psychodynamic theorists emphasized unconscious effects of other drives. Adler and Erikson emphasized, respectively, the drives for security and competence.

- Defense mechanisms serve to reduce conscious awareness of unacceptable or emotionally threatening thoughts, wishes, and feelings.

Defensive Styles as Personality Traits

- People classified as repressors routinely repress disturbing emotional feelings. Though they consciously experience little anxiety, their bodies react strongly to stressful situations. Such repression may help them cope cognitively in times of stress.

- In a longitudinal study of men, Vaillant found that defensive styles that involved less distortion of reality and led to more effective behavior were correlated with greater success in all areas of life.

The Humanistic Perspective

- Humanistic theories emphasize phenomenological reality (the self and world as perceived by the individual).

- Rogers proposed that individuals must move past social demands and judgments and make their own choices to become their real selves. Self-determination does correlate with greater life satisfaction.

- In Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, self-actualization (becoming one’s full self, living one’s dreams) is addressed only when more basic needs are adequately met.