17.4 Psychotherapy II: Cognitive and Behavioral Therapies

17

In what ways are cognitive and behavioral therapies similar to each other?

Cognitive and behavioral therapies are in many ways similar. Whereas psychodynamic and humanistic therapies tend to be holistic in their approach, focusing on the whole person, cognitive and behavioral therapies typically focus more directly and narrowly on the specific symptoms and problems that the client presents. Cognitive and behavioral therapists both are also very much concerned with data; they use objective measures to assess whether or not the treatment given is helping the client overcome the problem that is being treated. Many therapists today combine cognitive and behavioral methods, in what they call cognitive-behavioral therapy. Here, however, we will discuss the two separately, as they involve distinct assumptions and methods.

Principles of Cognitive Therapy

18

According to cognitive therapists, what is the source of clients’ behavioral and emotional problems?

Cognitive therapy arose in the 1960s as part of a shift in the overall field of psychology toward greater focus on the roles of thoughts, beliefs, and attitudes in controlling behavior. The field of psychology is filled with evidence that people’s beliefs and ingrained, habitual ways of thinking affect their behavior and emotions. Cognitive therapy begins with the assumption that people disturb themselves through their own, often illogical beliefs and thoughts. Maladaptive beliefs and thoughts make reality seem worse than it is and in that way produce anxiety or depression. The goal of cognitive therapy is to identify maladaptive ways of thinking and replace them with adaptive ways that provide a base for more effective coping with the real world. Unlike psychoanalysis, cognitive therapy generally centers on conscious thoughts, though such thoughts may be so ingrained and automatic that they occur with little conscious effort.

681

The two best-known pioneers of cognitive therapy are Albert Ellis and Aaron Beck. Both started their careers in the 1950s as psychodynamic therapists but became disenchanted with that approach (Beck & Weishaar, 2011; Ellis, 1986). Each was impressed by the observation that clients seemed to mentally distort their experiences in ways that quite directly produced their problems or symptoms. Ellis referred to his specific brand of cognitive therapy as rational-emotive therapy, highlighting his belief that rational thought will improve clients’ emotions.

Here we will look briefly at three general principles of cognitive therapy: the identification and correction of maladaptive beliefs and thoughts; the establishment of clear-cut goals and steps for achieving them; and the changing role of the therapist, from that of teacher early in the process to that of consultant later on.

Identifying and Correcting Maladaptive Beliefs and Habits of Thought

19

How did Ellis explain people’s negative emotions in terms of their irrational beliefs?

Different cognitive therapists take different approaches to pointing out their patients’ irrational ways of thinking. Beck, as you will see later (in the case example), tends to take a Socratic approach: Through questioning, he gets the patient to discover and correct his or her own irrational thought (Beck & Weishaar, 2011). Ellis, in contrast, took a more direct and blunt approach. He gave humorous names to certain styles of irrational thinking. Thus, musturbation is the irrational belief that one must have some particular thing or must act in some particular way in order to be happy or worthwhile. If a client said, “I have to get all A’s this semester in college,” Ellis might respond, “You’re musturbating again.” Awfulizing, in Ellis’s vocabulary, is the mental exaggeration of setbacks or inconveniences. A client who felt bad for a whole week because of a dent in her new car might be told, “Stop awfulizing.”

The following dialogue between Ellis (1962) and a client not only illustrates Ellis’s blunt style but also makes explicit his theory of the relationship between thoughts and emotions—a theory shared by most cognitive therapists. The client began the session by complaining that he was unhappy because some men with whom he played golf didn’t like him. Ellis, in response, claimed that the client’s reasoning was illogical—the men’s not liking him couldn’t make him unhappy.

Client: Well, why was I unhappy then?

Ellis: It’s very simple—as simple as A, B, C, I might say. A in this case is the fact that these men didn’t like you. Let’s assume that you observed their attitude correctly and were not merely imagining they didn’t like you.

Client: I assure you that they didn’t. I could see that very clearly.

Ellis: Very well, let’s assume they didn’t like you and call that A. Now, C is your unhappiness—which we’ll definitely have to assume is a fact, since you felt it.

Client: Damn right I did!

Ellis: All right, then: A is the fact that the men didn’t like you, and C is your unhappiness. You see A and C and you assume that A, their not liking you, caused your unhappiness. But it didn’t.

Client: It didn’t? What did, then?

Ellis: B did.

Client: What’s B?

Ellis: B is what you said to yourself while you were playing golf with those men.

Client: What I said to myself? But I didn’t say anything.

682

Ellis: You did. You couldn’t possibly be unhappy if you didn’t. The only thing that could possibly make you unhappy that occurs from without is a brick falling on your head, or some such equivalent. But no brick fell. Obviously, therefore, you must have told yourself something to make you unhappy. (Ellis, 1962, pp. 126, 127)

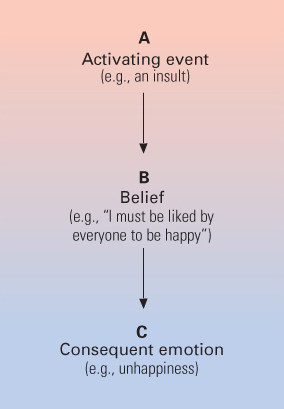

In this dialogue, Ellis invokes his famous ABC theory of emotions: A is the activating event in the environment, B is the belief that is triggered in the client’s mind when the event occurs, and C is the emotional consequence of the triggered belief (illustrated in Figure 17.3). Therapy proceeds by changing B, the belief. In this particular example, the man suffers because he believes irrationally that he must be liked by everyone (an example of musturbation), so if someone doesn’t like him, he is unhappy. The first step will be to convince the man that it is irrational to expect everyone to like him and that there is little or no harm in not being liked by some people.

Establishing Clear-Cut Goals and Steps for Achieving Them

20

What is the purpose of homework in cognitive therapy?

Once a client admits to the irrational and self-injurious nature of some belief or habit of thought, the next step is to help the client get rid of that belief or habit and replace it with a more rational and adaptive way of thinking. That takes hard work. Long-held beliefs and thoughts do not simply disappear once they are recognized as irrational. They occur automatically unless they are actively resisted.

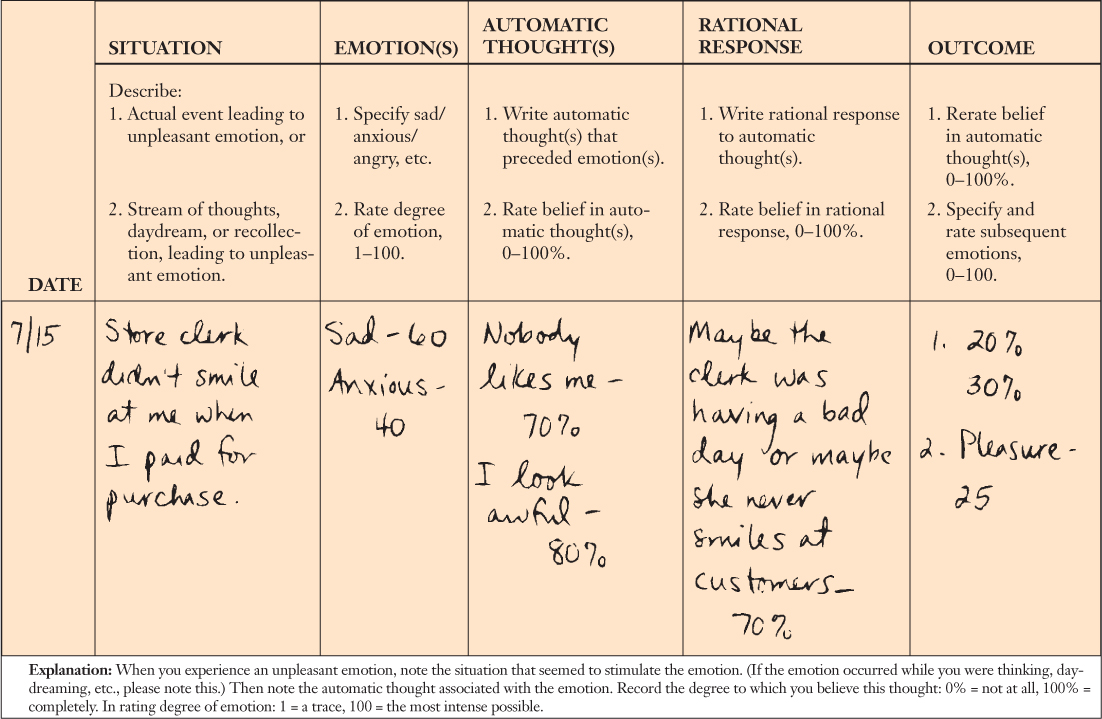

To help clients overcome their self-injurious ways of thinking, cognitive therapists often assign homework. For example, clients might be asked to keep a diary, or to fill out a form every day such as that depicted in Figure 17.4, in which they record the negative emotions they felt that day, describe the situations and automatic thoughts that accompanied those emotions, and describe a rational alternative thought that might make them feel less upset. Such exercises help train clients to become more aware of their automatic thoughts and, through awareness, change them. The diaries or charts also become a record of progress, by which the therapist and client can see if positive ways of thinking are increasing over time and negative emotions are decreasing.

Moving from a Teaching Role to a Consulting Role with the Client

21

In what sense is a cognitive therapist initially a teacher and later a consultant?

Cognitive therapists, unlike humanistic therapists, are quite directive in their approach. At least at the beginning, the relationship between cognitive therapist and client is fundamentally like that of a teacher and student. The therapist helps the client identify a set of goals, develops a curriculum for achieving those goals, assigns homework, and assesses the client’s progress using the most objective measures available. With time, however, as the client becomes increasingly expert in spotting and correcting his or her own maladaptive thoughts, the client becomes increasingly self-directive in the therapy, and the therapist begins to act more like a consultant and less like a teacher (Hazler & Barwick, 2001). Eventually, the client may meet with the therapist just occasionally to describe continued progress and to ask for advice when needed. When such advice is no longer needed, the therapy has achieved its goals and is over.

Although cognitive therapists are directive with clients, most of them acknowledge the value of some of the other tenets of humanistic therapy, particularly the value of maintaining a warm, genuine, and empathic relationship with their clients (Beck & Weishaar, 2011). In fact, increasingly, psychotherapists of all theoretical persuasions are acknowledging that empathy and understanding of the patient are an essential part of the therapeutic process (Hazler & Barwick, 2001; Weiner & Bornstein, 2009).

683

A Case Example: Beck’s Cognitive Treatment of a Depressed Young Woman

Aaron Beck, who at this writing has been applying and researching cognitive therapy for more than 50 years, is by far the most influential cognitive therapist. His earliest and best-known work was with patients with depression, but he has also developed cognitive therapy methods for treating anxiety, uncontrollable anger, and schizophrenia (Bowles, 2004). In the dialogue that follows (from Young, Beck & Weinberger, 1993, p. 264) we see him at work with a client referred to as Irene—a 29-year-old woman with two young children who was diagnosed with major depression.

22

How does Beck’s treatment of a depressed woman illustrate his approach to identifying and correcting maladaptive, automatic thoughts?

Irene had not been employed outside her home since marriage, and her husband, who had been in and out of drug treatment centers, was also unemployed. She was socially isolated and felt that people looked down on her because of her poor control over her children and her husband’s drug record. She was treated for three sessions by Beck and then was treated for a longer period by another cognitive therapist.

During the first session, Beck helped Irene to identify a number of her automatic negative beliefs, including: things won’t get better; nobody cares for me; and I am stupid. By the end of the session, she accepted Beck’s suggestion to try to invalidate the first of those thoughts by doing certain things for herself before the next session that might make life more fun. She agreed to take the children on an outing, visit her mother, go shopping, read a book, and find out about joining a tennis group—all things that she claimed she would like to do. Having completed that homework, she came to the second session feeling more hopeful. However, she began to feel depressed again when, during the session, she misunderstood a question that Beck asked her, which, she said, made her “look dumb.” Beck responded with a questioning strategy that helped her to distinguish between the fact of what happened (not understanding a question) and her belief about it (looking dumb):

684

Beck: OK, what is a rational answer to that [to why you didn’t answer the question]? A realistic answer?

Irene: … I didn’t hear the question right; that is why I didn’t answer it right.

Beck: OK, so that is the fact situation. And so, is the fact situation that you look dumb or you just didn’t hear the question right?

Irene: I didn’t hear the question right.

Beck: Or is it possible that I didn’t say the question in such a way that it was clear?

Irene: Possible.

Beck: Very possible. I’m not perfect so it’s very possible that I didn’t express the question properly.

Irene: But instead of saying you made a mistake, I would still say I made a mistake.

Beck: We’ll have to watch the video to see. Whichever. Does it mean if I didn’t express the question, if I made the mistake, does it make me dumb?

Irene: No.

Beck: And if you made the mistake, does it make you dumb?

Irene: No, not really.

Beck: But you felt dumb?

Irene: But I did, yeah.

Beck: Do you still feel dumb?

Irene: No. Right now I feel glad. I’m feeling a little better that at least somebody is pointing all these things out to me because I have never seen this before. I never knew that I thought that I was that dumb. (Young, Beck & Weinberger, 1993, p. 264)

As homework between the second and third sessions, Beck gave Irene the assignment of catching, writing down, and correcting her own dysfunctional thoughts, using a form similar to the one shown in Figure 17.4. Subsequent sessions were aimed at eradicating each of her depressive thoughts, one by one, and reinforcing the steps she was taking to improve her life. Progress was rapid. Irene felt increasingly better about herself. During the next several months, she joined a tennis league, got a job, took a college course in sociology, and left her husband after trying and failing to get him to develop a better attitude toward her or to join her in couples therapy. By this time, according to Beck, she was cured of her depression, had created for herself a healthy environment, and no longer needed therapy.

Cognitive therapy is the basis for some new types of therapy. For example, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy incorporates traditional aspects of cognitive therapy with mindfulness and mindfulness meditation, which involves becoming aware of all incoming thoughts and feelings, accepting them, but not reacting to them, all in the best Buddhist tradition. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy has been shown to be effective in depression (Manicavasgar et al., 2011; Piet & Hougaard, 2011). Similarly, dialectical behavior therapy (Linehan & Dimeff, 2001) uses aspects of cognitive therapy plus “mindful awareness” (much like mindfulness) along with training in emotion regulation to successfully treat people with borderline personality disorder, perhaps the first effective therapy for this disorder (Kliem et al., 2010).

685

Principles of Behavior Therapy

23

How is behavior therapy distinguished from cognitive therapy?

If a cognitive therapist is a teacher, a behavior therapist is a trainer. While cognitive therapy deals with maladaptive habits of thought, behavior therapy deals directly with maladaptive behaviors. Behavior therapy is rooted in the research on basic learning processes initiated by such pioneers as Ivan Pavlov, John B. Watson, and B. F. Skinner (discussed in Chapter 4). Unlike all the other psychotherapy approaches we have discussed, behavior therapy is not fundamentally talk therapy. Rather, in behavior therapy clients are exposed by the therapist to new environmental conditions that are designed to retrain them so that maladaptive habitual or reflexive ways of responding become extinguished and new, healthier habits and reflexes are conditioned.

In other regards, behavior therapy is much like cognitive therapy, and, as we noted earlier, the approaches are often combined, in cognitive-behavioral therapy. Behavior therapy, like cognitive therapy, is very much symptom oriented and concerned with immediate, measurable results. Two of the most common types of treatment in behavior therapy, discussed below, are contingency management therapy to modify habits and exposure therapy to overcome unwanted fears.

Contingency Management: Altering the Relationship Between Actions and Rewards

The basic principle of operant conditioning, discussed in Chapter 4, is that behavioral actions are reinforced by their consequences. People, like other animals, learn to behave in ways that bring desired consequences and to avoid behaving in ways that do not. When a behavior therapist learns that a client is behaving in ways that are harmful to him- or herself, or to others, the first question the therapist might ask is this: What reward is this person getting for this behavior, which leads him or her to continue it? The next step, once the reward is understood, is to modify the behavior–reward contingency so that desired actions are rewarded and undesired ones are not. The broad term for all therapy programs that alter the contingency between actions and rewards is contingency management.

24

How has contingency management been used to improve children’s behavior and motivate abstinence in drug abusers?

For example, if parents complain to a behavior therapist that their child is acting in aggressive and disruptive ways at home, the therapist might ask the parents to keep a record, for a week or more, of each instance of such misbehavior and of how they or others in the family responded. From that record, the therapist might learn that the child is gaining desired attention through misbehavior. The therapist might then work out a training program in which the parents agree to attend more to the child when he is behaving in desired ways and to ignore the child, or provide some clearly negative consequence (such as withdrawing some privilege), when he is behaving in undesired ways. This sort of behavioral work with families, aimed at altering the contingencies between actions and rewards at home, is referred to as parent management training (Kazdin, 2003). Contingency management is the principal tool used in applied behavior analysis, discussed in Chapter 4 (p. 124), which focuses on changing some target behaviors, such as nail biting, head banging for a child with autism, or study habits for a fourth grader, by changing patterns of reinforcements.

In recent years, contingency management has been instituted in many community drug rehabilitation programs. In these programs, patients who remain drug free for specified periods of time, as measured by regular urine tests, receive vouchers that they can turn in for valued prizes. Such programs have proven quite successful in encouraging cocaine and heroin abusers to go many weeks without taking drugs, and in at least some cases these programs are less expensive than other, more standard treatments (Barry et al., 2009; Higgins et al., 2007).

686

Exposure Treatments for Unwanted Fears

25

What is the theoretical rationale for treating specific phobias by exposing clients to the feared objects or situations?

Behavior therapy has proven especially successful in treating specific phobias, in which the person fears something well defined, such as high places or a particular type of animal (Emmelkamp, 2004). From a behavioral perspective, fear is a reflexive response, which through classical conditioning can come to be triggered by various nondangerous as well as dangerous stimuli. An unconditioned stimulus for fear is one that elicits the response even if the individual has had no previous experience with the stimulus; a conditioned stimulus for fear is one that elicits the response only because the stimulus was previously paired with some fearful event in the person’s experience. Opinions may differ as to whether a particular fear, such as a fear of snakes, is unconditioned or conditioned (unlearned or learned), but in practice this does not matter because the treatment is the same in either case.

A characteristic of the fear reflex, whether conditioned or unconditioned, is that it declines and gradually disappears if the eliciting stimulus is presented many times or over a prolonged period in a context where no harm comes to the person. In the case of an unconditioned fear reflex—such as the startle response to a sudden noise—the decline is called habituation. In the case of a conditioned fear reflex, the decline that occurs when the conditioned stimulus is presented repeatedly without the unconditioned stimulus is called extinction. For example, if a person fears all dogs because of once having been bitten, then prolonged exposure to various dogs (the conditioned stimuli) in the absence of being bitten (the unconditioned stimulus) will result in reduction or eradication of the fear. Any treatment for an unwanted fear or phobia that involves exposure to the feared stimulus in order to habituate or extinguish the fear response is referred to as an exposure treatment (Moscovitch et al., 2009). Behavior therapists have developed three different means to present feared stimuli to clients in such treatments (Krijn et al., 2004).

26

What are three ways of exposing clients to feared objects or situations, and what are the advantages of each?

One means is imaginal exposure. A client in this form of treatment is instructed to imagine a particular, moderately fearful scene as vividly as possible until it no longer seems frightening. Then the client is instructed to imagine a somewhat more fearful scene until that no longer seems frightening. In this way the client gradually works up to the most feared scene. For example, a woman afraid of heights might be asked first to imagine that she is looking out a second-floor window, then a third-floor window, and so on, until she can imagine, without strong fear, that she is looking down from the top of a skyscraper. An assumption here is that the ability to remain calm while imagining the previously feared situation will generalize so that the person will be able to remain calm in the actual situation. Research involving long-term follow-up has shown that imaginal exposure techniques can be quite effective in treating specific phobias (Zinbarg et al., 1992).

The most direct exposure technique is in vivo exposure—that is, real-life exposure. With this technique the client, usually accompanied by the therapist or by some other comforting and encouraging helper, must force him- or herself to confront the feared situation in reality. For example, to overcome a fear of flying, the client might begin by going to the airport and watching planes take off and land until that can be done without fear. Then, through a special arrangement with an airline, the client might enter a stationary plane and sit in it for a while, until that can be done without fear. Finally, the client goes on an actual flight—perhaps just a short one the first time. Research suggests that in vivo exposure is generally more effective than imaginal exposure when both are possible (Emmelkamp, 2004). However, in vivo exposure is usually more time consuming and expensive, and is often not practical because the feared situation is difficult to arrange for the purpose of therapy.

687

Today, with advanced computer technology, a third means of exposure is possible and is rapidly growing in use—virtual reality exposure, in which patients wear goggles and experience three-dimensional images that simulate real-world objects and situations. Virtual worlds have been developed for exposure treatments for many different phobias, including fear of heights, fear of flying, claustrophobia (fear of being in small, enclosed spaces), spider phobia, and fear of public speaking (Krijn et al., 2004), as well as anxiety disorders (Antony, 2011). Results to date suggest that virtual reality exposure is quite effective (Krijn et al., 2004; Parsons & Rizzo, 2008). In one research study, for example, all nine participants, who came with strong fears of flying, overcame their fears within six 1-hour sessions of virtual exposure—exposure in which they progressed gradually through virtual experiences of going to an airport, entering a plane, flying, looking out the plane window, and feeling and hearing turbulence while flying (Botella et al., 2004). After the therapy, all of them were able to take an actual plane fight with relatively little fear.

A Case Example: Miss Muffet Overcomes Her Spider Phobia

Our case example of behavior therapy is that of a woman nicknamed Miss Muffet by her therapists (Hoffman, 2004). For 20 years prior to her behavioral treatment, Miss Muffet had suffered from an extraordinary fear of spiders, a fear that had led to a diagnosis not just of spider phobia but also obsessive-compulsive disorder. Her obsessive fear of spiders prompted her to engage in such compulsive rituals as regularly fumigating her car with smoke and pesticides, sealing her bedroom windows with duct tape every night, and sealing her clothes in plastic bags immediately after washing them. She scanned constantly for spiders wherever she went, and she avoided places where she had ever encountered spiders. By the time she came for behavior therapy her spider fear was so intense that she found it difficult to leave home at all.

27

How did virtual exposure treatment help Miss Muffet overcome her fear of spiders?

Miss Muffet’s therapy, conducted by Hunter Hoffman (2004) and his colleagues, consisted of ten 1-hour sessions of virtual reality exposure. In the first session she navigated through a virtual kitchen, where she encountered a huge virtual tarantula. She was asked to approach this spider as closely as she could, using a handheld joystick to move forward in the three-dimensional scene. In later sessions, as she became less fearful of approaching the virtual tarantula, she was instructed to reach out and “touch” it. To create the tactile effect of actually touching the spider, the therapist held out a fuzzy toy spider, which she felt with her real hand as she saw her virtual hand touch the virtual spider.

In other sessions, she encountered other spiders of various shapes and sizes. On one occasion she was instructed to pick up a virtual vase, out of which wriggled a virtual spider. On another, a virtual spider dropped slowly to the floor of the virtual kitchen, directly in front of her, as sound effects from the horror movie Psycho were played through her headphones. The goal of the therapy was to create spider experiences that were more frightening than any she would encounter in the real world, so as to convince her, at a gut emotional level, that encountering real spiders would not cause her to panic or go crazy. As a test, after the 10 virtual reality sessions, Miss Muffet was asked to hold a live tarantula (a large, hairy, fearsome looking, but harmless spider), which she did with little fear, even while the creature crawled partway up her arm.

688

SECTION REVIEW

Cognitive and behavioral therapy—both problem centered—are often combined.

Principles of Cognitive Therapy

- Cognitive therapy is based on the idea that psychological distress results from maladaptive beliefs and thoughts.

- The cognitive therapist works to identify maladaptive thoughts and beliefs, convince the client of their irrationality, and help the client eliminate them along with the unpleasant emotions they provoke.

- To help the client replace the old, habitual ways of thinking with more adaptive ways, cognitive therapists often assign homework (such as writing down and correcting irrational thoughts). Progress is objectively measured. As the client can assume more of the responsibility, the therapist becomes less directive.

- A case example shows Aaron Beck’s cognitive treatment of a depressed young woman who came to see how her automatic negative thoughts (such as “I am stupid”) were affecting her.

Principles of Behavior Therapy

- The goals of behavior therapy are to extinguish maladaptive responses and to condition healthier responses by exposing clients to new environmental conditions.

- Contingency management programs are based on operant-conditioning principles. They modify behavior by modifying behavior–reward contingencies.

- Exposure treatments, based on classical conditioning, are used to habituate or extinguish reflexive fear responses in phobias. Three techniques are imaginal exposure, in vivo (real-life) exposure, and virtual reality exposure.

- In a case example, virtual reality exposure therapy helped “Miss Muffet” overcome a debilitating fear of spiders.