2.1 Lessons from Clever Hans

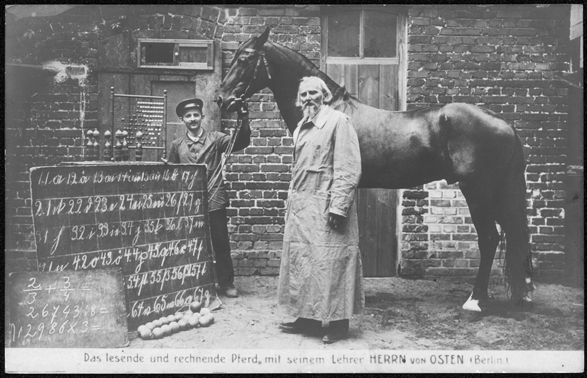

This is a true story that took place in Germany near the beginning of the twentieth century. The horse was Clever Hans, famous throughout Europe for his ability to answer questions, and the psychologist was Oskar Pfungst. In a preface to the original account (Pfungst, 1911/1965), James Angell wrote, “Were it offered as fiction, it would take high rank as a work of imagination. Being in reality a sober fact, it verges on the miraculous.” We tell the story here because of the lessons it teaches about scientific attitude and methods.

30

The Mystery

Hans’s owner, a Mr. von Osten, was an eccentric retired schoolteacher and devoted horseman who had long believed that horses would prove to be as intelligent as people if only they were given a proper education. To test his theory, von Osten spent 4 years tutoring Hans in the manner employed in the most reputable German schools for children. Using flash cards, counting frames, and the like, he set about teaching his horse reading, arithmetic, history, and other scholarly disciplines. He always began with simple problems and worked toward more complex ones, and he rewarded Hans frequently with praise as well as carrots. Recognizing that horses lack the vocal apparatus needed for speech, von Osten taught Hans to spell out words using a code in which the letters of the alphabet were translated into hoof taps and to answer yes-no questions by tossing his head up and down for “yes” and back and forth for “no.” After 4 years of this training, Hans was able to answer practically any question that was put to him in either spoken or written German, whether about geography, history, science, literature, mathematics, or current events. Remarkably, he could also answer questions put to him in other languages, even though he had never been trained in them.

Now, you might think that von Osten was a charlatan, but he wasn’t. He genuinely believed that his horse could read and understand a variety of languages, could perform mathematical calculations, and had acquired a vast store of knowledge. He never charged admission or sought other personal gain for displaying Hans, and he actively sought out scientists to study the animal’s accomplishments. Indeed, many scientists, including some eminent zoologists and psychologists, came to the conclusion that von Osten’s claims were true. The evidence that most convinced them was Hans’s ability to answer questions even when von Osten was not present, a finding that seemed to rule out the possibility that the horse depended on secret signals from his master. Moreover, several circus trainers, who specialized in training animals to give the appearance of answering questions, studied Hans and could find no evidence of trickery.

The Solution

1

How did Clever Hans give the appearance of answering questions, and how did Oskar Pfungst unveil Hans’s methods?

Hans’s downfall finally came when the psychologist Oskar Pfungst performed a few simple experiments. Pfungst theorized that Hans answered questions not through understanding them and knowing the answers but through responding to visual signals inadvertently produced by the questioner or other observers. Consistent with this theory, Pfungst found that the animal failed to answer questions when he was fitted with blinders so that he could not see anyone, and that even without blinders he could not answer questions unless at least one person in his sight knew the answer. With further study, Pfungst discovered just what the signals were.

31

Immediately after asking a question that demanded a hoof-tap answer, the questioner and other observers would naturally move their heads down just a bit to observe the horse’s hoof. This, it turned out, was the signal for Hans to start tapping. To determine whether Hans would be correct or not, the questioner and other observers would then count the taps and, unintentionally, make another response as soon as the correct number had been reached. This response varied from person to person, but a common component was a slight upward movement of either the whole head or some facial feature, such as the eyebrows. This, it turned out, was the signal for Hans to stop tapping. Hans’s yes-no headshake responses were also controlled by visual signals. Questioners and observers would unconsciously produce slight up-and-down head movements when they expected the horse to answer yes and slight back-and-forth head movements when they expected him to answer no, and Hans would shake his head accordingly.

All the signals that controlled Hans’s responses were so subtle that even the most astute observers had failed to notice them until Pfungst pointed them out. And Pfungst himself reported that the signals occurred so naturally that, even after he had learned what they were, he had to make a conscious effort to prevent himself from sending them after asking a question. For 4 years, von Osten had believed that he was communicating scholarly information to Hans, when all he had really done was teach the horse to make a few simple responses to a few simple, though minute, gestures.

Facts, Theories, and Hypotheses

2

How are facts, theories, and hypotheses related to one another in scientific research?

The story of Clever Hans illustrates the roles of facts, theories, and hypotheses in scientific research. A fact, also referred to as an observation, is an objective statement, usually based on direct observation, that reasonable observers agree is true. In psychology, facts are usually particular behaviors, or reliable patterns of behaviors, of persons or animals. When Hans was tested in the manner typically employed by von Osten, the horse’s hoof taps or headshakes gave the appearance that he was answering questions correctly. That is a fact, which no one involved in the adventure disputed.

A theory is an idea, or a conceptual model, that is designed to explain existing facts and make predictions about new facts that might be discovered. Any prediction about new facts that is made from a theory is called a hypothesis. Nobody knows what facts (or perhaps delusions) led von Osten to develop his theory that horses have humanlike intelligence. However, once he conceived his theory, he used it to hypothesize that his horse, Hans, could learn to give correct answers to verbally stated problems and questions. The psychologist, Pfungst, had a quite different theory of equine intelligence: Horses don’t think like humans and can’t understand human language. In keeping with this theory, and to explain the fact that Hans seemed to answer questions correctly, Pfungst developed the more specific theory that the horse responded to visual cues produced by people who were present and knew the answers. This theory led Pfungst to hypothesize that Hans would not answer questions correctly if fitted with blinders or if asked questions to which nobody present knew the answer.

Facts lead to theories, which lead to hypotheses, which are tested with experiments or other research studies, which lead to new facts, which sometimes lead to new theories, which…. That is the cycle of science, whether we are speaking of psychology, biology, physics, or any other scientific endeavor. As a colleague of ours likes to say, “Science walks on two legs: theory and facts.” Theory without facts is merely speculation, and facts without theory are simply observations without explanations.

32

The Lessons

In addition to illustrating the roles of fact, theory, and hypothesis, the story contains three more specific lessons about scientific research:

3

How does the Clever Hans story illustrate (1) the value of skepticism, (2) the value of controlled experimentation, and (3) the need for researchers to avoid communicating their expectations to subjects?

- The value of skepticism. People are fascinated by extraordinary claims and often act as though they want to believe them. This is as true today as it was in the time of Clever Hans. We have no trouble at all finding otherwise rational people who believe in astrology, psychokinesis, water divining, telepathy, or other occult phenomena, despite the fact that all these have consistently failed when subjected to controlled tests (Smith, 2010). Von Osten clearly wanted to believe that his horse could do amazing things, and to a lesser degree, the same may have been true of the scholars who had studied the horse before Pfungst. Pfungst learned the truth partly because he was highly skeptical of such claims. Instead of setting out to prove them correct, he set out to prove them wrong. His skepticism led him to look more carefully; to notice what others had missed; to think of an alternative, more mundane explanation; and to pit the mundane explanation against the astonishing one in controlled tests.

In general, the more extraordinary a claim is—the more it deviates from accepted scientific principles—the stronger the evidence for the new theory needs to be. To suggest a complex, extraordinary explanation of some behavior requires that all simple and conventional explanations be considered first and judged inadequate. Moreover, the simpler the explanation is, the better it tends to be. This is referred to as parsimony, or Occam’s razor (after the medieval philosopher William of Ockham). Basically, when there are two or more explanations that are equally able to account for a phenomenon, the simplest explanation is usually preferred.

Skepticism should be applied not only to extraordinary theories that come from outside of science but also to the usually more sober theories produced by scientists themselves. The ideal scientist always tries to disprove theories, even those that are his or her own. The theories that scientists accept as correct, or most likely to be correct, are those that could potentially be disproved but have survived all attempts so far to disprove them. - The value of careful observations under controlled conditions. Pfungst solved the mystery of Clever Hans by identifying the conditions under which the horse could and could not respond correctly to questions. He tested Hans repeatedly, with and without blinders, and recorded the percentage of correct answers in each condition. The results were consistent with the theory that the animal relied on visual signals. Pfungst then pursued the theory further by carefully observing Hans’s examiners to see what cues they might be sending. And when he had an idea what the cues might be, he performed further experiments in which he deliberately produced or withheld the signals and recorded their effects on Hans’s hoof-tapping and head-shaking responses. Careful observation under controlled conditions is a hallmark of the scientific method.

- The problem of observer-expectancy effects. In studies of humans and other sentient animals, the observers (the people conducting the research) may unintentionally communicate to subjects (the individuals being studied) their expectations about how they “should” behave, and the subjects, intentionally or not, may respond by doing just what the researchers expect. The same is true in any situation in which one person administers a test to another. Have you ever taken an oral quiz and found that you could tell whether you were on the right track by noting the facial expression of your examiner? By tentatively trying various tracks, you may have finally hit on just the answer that your examiner wanted. Clever Hans’s entire ability depended on his picking up such cues. We will discuss the general problem of expectancy effects later in this chapter (in the section on avoiding bias).

33

SECTION REVIEW

The case of the horse named Clever Hans illustrates a number of issues fundamental to scientific research.

Facts, Theories, and Hypotheses

- Objective observations about behavior (facts) lead psychologists to create conceptual models or explanations (theories), which make specific, testable predictions (hypotheses).

- Pfungst drew testable hypotheses from his theory that Hans was guided by visual cues from onlookers.

The Importance of Skepticism

- Skeptics seek to disprove claims. That is the logical foundation of scientific testing.

- A scientific theory becomes more believable as repeated, genuine attempts to disprove it fail.

- Pfungst’s skepticism caused him to test, rather than simply accept, claims about Hans’s abilities.

Observation and Control

- To test hypotheses, scientists control the conditions in which they make observations so as to rule out alternative explanations.

- Pfungst measured Hans’s performance in conditions arranged specifically to test his hypothesis—with and without blinders, for example.

Observer-Expectancy Effects

- Science is carried out by people who come to their research with certain expectations.

- In psychology, the subjects—the people and animals under study—may perceive the observer’s expectations and behave accordingly.

- Cues from observers led Hans to give responses that many misinterpreted as signs of vast knowledge.