3.7 Evolutionary Analyses of Hurting and Helping

Human beings, like other animals, are motivated both to hurt and to help one another in the struggle to survive and reproduce. From an evolutionary perspective, other members of one’s species are competitors for food, mates, safe places to live, and other limited resources. Ultimately, such competition is the foundation of aggression. Yet, at the same time, others of one’s kind are potential helpmates. Many life-promoting tasks can be accomplished better by two or more together than by one struggling alone. The human drama, like that of other social species, involves the balancing of competitiveness with the need for others’ help. Let us look first at the grim topic of aggression and then end, more pleasantly, with cooperation.

Sex Differences in Aggression

Aggression, as the term is used here, is typically defined as behavior intended to harm another member of the same species. Brain mechanisms that motivate and organize such behavior have evolved because they help animals acquire and retain resources needed to survive and reproduce. As you saw in the previous section, much animal aggression centers on mating. Polygynous males and polyandrous females fight for mates; monogamous males fight to prevent other males from copulating with their mates; monogamous females fight to keep other females from leading their mates away; and promiscuous females fight to keep immigrating females from competing for resources (Kahlenberg et al., 2008; Tobias & Seddon, 2000). Aggression can also serve to protect a feeding ground for oneself and one’s offspring, to drive away individuals that may be a threat to one’s young, and to elevate one’s status within a social group. Much could be said from an evolutionary perspective about all aspects of aggression, but here we will focus just on sex differences in how aggression is manifested.

Why Male Primates Are Generally More Violent Than Female Primates

Among most species of mammals, and especially among primates, males are much more violently aggressive than are females. Female primates are not unaggressive, but their aggression is typically aimed directly toward obtaining resources and defending their young. When they have achieved their ends, they stop fighting. Male primates, in contrast, seem at times to go out of their way to pick fights, and they are far more likely to maim or kill their opponents than are females.

41

How is male violence toward infants, toward other males, and toward females explained from an evolutionary perspective?

Most of the violence perpetrated by male primates has to do directly or indirectly with sex. Male monkeys and apes of many species have been observed to kill infants fathered by others, apparently as a means to get the females to stop lactating so they will ovulate again and become sexually active. Males also fight with one another, sometimes brutally, to gain access to a particular female or to raise their rank in the dominance hierarchy of the troop. High rank generally increases both their attractiveness to females and their ability to intimidate sexual rivals (Cowlishaw & Dunbar, 1991). Males are also often violent toward females; they use violence to force copulation or to prevent the female from copulating with other males. All of these behaviors have been observed in chimpanzees and many other primate species (Goodall, 1986; Smuts, 1992; Wittig & Boesch, 2003).

Evolution, remember, is not a moral force. It promotes those behaviors that tend to get one’s genes passed on to the next generation. Female primates, because of their higher parental investment, don’t need to fight to get the opposite sex interested in them. Moreover, aggression may have a higher cost for females than for males. The female at battle risks not just her life but also that of any fetus she is gestating or young she is nursing—the repositories of her genes (Campbell, 1999). The male at battle risks just himself; in the cold calculus of evolution, his life isn’t worth anything unless he can get a female to mate with him. Genes that promote mating, by whatever means, proliferate, and genes that fail to promote it vanish.

94

Male Violence in Humans

Humans are no exception to the usual primate rule. Cross-cultural studies show that everywhere men are more violent—more likely to maim or kill—than are women. In fact, in a survey of cross-cultural data on this issue, Martin Daly and Margo Wilson (1988) were unable to find any society in which the number of women who killed other women was even one-tenth as great as the number of men who killed other men. On average, in the data they examined, male-male killings outnumbered female-female killings by more than 30 to 1. One might construe a scenario through which such a difference in violence would be purely a product of learning in every culture, but the hypothesis that the difference resides at least partly in inherited sex differences seems more plausible.

According to Daly and Wilson’s analyses, the apparent motives underlying male violence and homicide are very much in accord with predictions from evolutionary theory. Among the leading motives for murder among men in every culture is sexual jealousy. In some cultures, men are expected to kill other men who have sex with their wives (Symons, 1979), and in others, such murders are common even though they are illegal (Daly & Wilson, 1988). Men also fight over status, which can affect their degree of success in mating (Daly & Wilson, 1990). One man insults another and then the two fight it out—with fists, knives, or guns. And men, like many male monkeys and apes, often use violence to control females. In the United States and Canada, between 25 and 30 percent of women are battered by their current or former mate at some time in their lives (Randall & Haskell, 1995; Williams & Hawkins, 1989). Analyses of domestic violence cases indicate that much of it has to do with the man’s belief (often unfounded) that his partner has been or might become sexually unfaithful (Goetz, 2008; Peters et al., 2002).

Patterns of Helping

From an evolutionary perspective, helping can be defined as any behavior that increases the survival chance or reproductive capacity of another individual. Given this definition, it is useful to distinguish between two categories of helping: cooperation and altruism.

Cooperation occurs when an individual helps another while helping itself. This sort of helping happens all the time in the animal world and is easy to understand from an evolutionary perspective. It occurs when a mated pair of foxes work together to raise their young, a pack of wolves work together to kill an antelope, or a group of chimpanzees work together to chase off a predator or a rival group of chimpanzees. Most of the advantages of social living lie in cooperation. By working with others for common ends, each individual has a better chance of survival and reproduction than it would have alone. Whatever costs accrue are more than repaid by the benefits. Human beings everywhere live in social groups and derive the benefits of cooperation. Those who live as our ancestors did cooperate in hunting and gathering food, caring for children, building dwellings, defending against predators and human invaders, and, most human of all, in exchanging, through language, information that bears on all aspects of the struggle for survival. Cooperation, and behaving fairly toward other people in general, develops quite early in life, suggesting that it is not simply a reflection of children bowing to the requests and admonishments of their parents but an aspect of sociality that runs deep in human nature (Tomasello, 2009; Warneken & Melis, 2012).

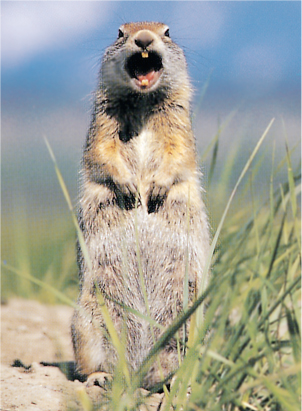

Altruism, in contrast, occurs when an individual helps another while decreasing its own survival chance or reproductive capacity. This is less common than cooperation, but many animals do behave in ways that at least appear to be altruistic. For example, some animals, including female ground squirrels, emit a loud, distinctive call when they spot an approaching predator. The cry warns others of the predator’s approach and, at the same time, tends to attract the predator’s attention to the caller (Sherman, 1977). (See Figure 3.20.) The selfish response would be to remain quiet and hidden, or to move away quietly, rather than risk being detected by warning others. How can such behavior be explained from an evolutionary perspective? As Trivers (1971) pointed out long ago, any evolutionary account of apparent altruism must operate by showing that from a broader perspective, focusing on the propagation of one’s genes, the behavior is not truly altruistic. Evolutionists have developed two broad theories to account for ostensible altruism in animals: the kin selection theory and the reciprocity theory.

95

The Kin Selection Theory of Altruism

42

How do the kin selection and reciprocity theories take the altruism out of “altruism”? What observations show that both theories apply to humans as well as to other animals?

The kin selection theory holds that behavior that seems to be altruistic came about through natural selection because it preferentially helps close relatives, who are genetically most similar to the helper (Hamilton, 1964). What actually survives over evolutionary time, of course, is not the individual but the individual’s genes. Any gene that promotes the production and preservation of copies of itself can be a fit gene, from the vantage point of natural selection, even if it reduces the survival chances of a particular carrier of the gene.

Imagine a ground squirrel with a rare gene that promotes the behavior of calling out when a predator is near. The mathematics of inheritance are such that, on average, one-half of the offspring or siblings of the individual with this gene would be expected to have the same gene, as would one-fourth of the nieces or nephews and one-eighth of the cousins. Thus, if the altruist incurred a small risk (Δ) to its own life while increasing an offspring’s or a sibling’s chances of survival by more than 2Δ, a niece’s or nephew’s by more than 4Δ, or a cousin’s by more than 8Δ, the gene would increase in the population from one generation to the next.

Many research studies have shown that animals do help kin more than nonkin. For example, ground squirrels living with kin are more likely to emit alarm calls than are those living with nonkin (Sherman, 1977). Chimpanzees and other primates are more likely to help kin than nonkin in all sorts of ways, including sharing food, providing assistance in fights, and helping take care of young (Goodall, 1986; Nishida, 1990). Consistent with the mathematics of genetic relatedness, macaque monkeys have been observed to help their brothers and sisters more readily than their cousins and their cousins more readily than more distant relatives (Silk, 2002). In these examples, the helpers can apparently distinguish kin from nonkin, and this ability allows them to direct help selectively to kin (Pfennig & Sherman, 1995; Silk, 2002). In theory, however, altruistic behavior can evolve through kin selection even without such discrimination. A tendency to help any member of one’s species indiscriminately can evolve if the animal’s usual living arrangements are such that, by chance alone, a sufficiently high percentage of help is directed toward kin.

Cross-cultural research shows that among humans the selective helping of kin more than nonkin is common everywhere (Essock-Vitale & McGuire, 1980). If a mother dies or for other reasons is unable to care for a child, the child’s grandmother, aunt, or other close relative is by far the most likely adopter (Kurland, 1979). Close kin are also most likely to share dwellings or land, hunt together, or form other collaborative arrangements. On the other side of the same coin, studies in Western culture indicate that genetic kin living in the same household are less often violent toward one another than are nonkin living in the same household (Daly & Wilson, 1988), and studies in other cultures have shown that villages in which most people are closely related have less internal friction than those in which people are less closely related (Chagnon, 1979). People report feeling emotionally closer to their kin than to their nonkin friends, even if they live farther away from the former than from the latter and see them less often (Neyer & Lang, 2003).

96

When leaders call for patriotic sacrifice or universal cooperation, they commonly employ kinship terms (Johnson, 1987). At times of war, political leaders ask citizens to fight for the “motherland” or “fatherland”; at other times, religious leaders and humanists strive to promote world peace by speaking of our “brothers and sisters” everywhere. The terms appeal to our tendencies to be kind to relatives. Our imagination and intelligence allow us, at least sometimes, to extend our concept of kinship to all humanity.

The Reciprocity Theory of Apparent Altruism

The reciprocity theory provides an account of how acts of apparent altruism can arise even among nonkin. According to this theory, behaviors that seem to be altruistic are actually forms of long-term cooperation (Trivers, 1971). Computer simulations of evolution have shown that a genetically induced tendency to help nonkin can evolve if it is tempered by (a) an ability to remember which individuals have reciprocated such help in the past and (b) a tendency to refrain from helping again those who failed to reciprocate previous help. Under these conditions, helping another is selfish because it increases the chance of receiving help from that other in the future.

Behavior fitting this pattern is found in various niches of the animal world. As one example, vampire bats frequently share food with unrelated members of their species that have shared food with them in the past (Wilkinson, 1988). As another example, bonobo females that establish friendship coalitions and are very effective in helping one another are often unrelated to one another, having immigrated from different natal troops (Kano, 1992; Parish & de Waal, 2000). The help each gives the others in such acts as chasing off offending males is reciprocated at another time.

The greatest reciprocal helpers of all, by far, are human beings. People in every culture feel a strong drive to return help that is given to them (Gouldner, 1960; Hill, 2002). Humans, more than any other species, can keep track of help given, remember it over a long period of time, and think of a wide variety of ways of reciprocating. Moreover, to ensure reciprocity, people everywhere have a highly developed sense of fairness and behave in ways that punish those who fail to fulfill their parts in reciprocal relationships (Fehr & Fischbacher, 2003). Certain human emotions seem to be well designed, by natural selection, to promote reciprocity. We feel gratitude toward those who help us, pride when we return such help, guilt when we fail to return help, and anger when someone fails repeatedly to return help that we have given. Humans also help others, including others who may never be able to reciprocate, in order to develop a good reputation in the community at large, and those with a good reputation are valued and helped by the community (Fehr & Fischbacher, 2003).

Final Words of Caution: Two Fallacies to Avoid

Before closing this chapter it would be worthwhile to reiterate and expand on two points that we have already made: (1) Natural selection is not a moral force, and (2) our genes do not control our behavior in ways that are independent of the environment. These statements contradict two fallacious ideas that often creep into the evolutionary thinking of people who don’t fully understand natural selection and the nature of genetic influences.

97

The Naturalistic Fallacy

43

Why is it considered a fallacy to equate “natural” with “right”? How did that fallacy figure into the philosophy of Herbert Spencer?

The naturalistic fallacy is the equation of “natural” with “moral” or “right.” If natural selection favors sexual promiscuity, then promiscuity is right. If male mammals in nature dominate females through force, then aggressive dominance of women by men is right. If natural selection promotes self-interested struggle among individuals, then selfishness is right. Such equations are logically indefensible because nature itself is neither moral nor immoral except as judged so by us. Morality is a product of the human mind. We have acquired the capacity to think in moral terms, and we can use that capacity to develop moral philosophies that go in many possible directions, including those that favor real altruism and constrain individual self-interest for the good of the larger community (Hauser, 2006).

The term naturalistic fallacy was coined by the British philosopher G. E. Moore (1903) as part of an argument against the views of another British philosopher, Herbert Spencer (1879). A contemporary of Darwin, Spencer considered himself a strong believer in Darwin’s theory, and his goal was to apply it to the spheres of social philosophy and ethics. Unlike Darwin, Spencer seemed to imply in his writings that natural selection is guided by a moral force. He distinguished between “more evolved” and “less evolved” behaviors in nature and suggested that “more evolved” means more moral. Although Spencer wrote of cooperation as highly evolved and virtuous, his philosophy leaned more toward the virtues of individualism and competition. Spencer’s writings were especially popular in the United States, where they were championed by such industrialists as John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie (Rachels, 1990).

It was Spencer, not Darwin, who popularized the phrase “survival of the fittest”; and some of the so-called social Darwinists, who were inspired by Spencer, used that phrase to justify even the most ruthless extremes of capitalism. In their view, the fittest were those who rose to the top in unchecked capitalism, and the unfit were those who fell into poverty or starvation.

Darwin himself was not seduced by the naturalistic fallacy. He was repulsed by much of what he saw in nature and marveled at the human ability to rise, sometimes, above it. He conscientiously avoided phrases such as “more evolved” that would imply that evolution is a moral force, and he felt frustrated by his inability to stop others from assuming that it is. In a letter to a friend, shortly after publication of The Origin of Species, he wrote wryly, “I have noted in a Manchester newspaper a rather good squib, showing that I have proved ‘might is right’ and therefore Napoleon is right and every cheating tradesman is also right” (Rachels, 1990).

The Deterministic Fallacy

44

Why is it a mistake to believe that characteristics that are influenced by genes cannot be changed except by modifying genes?

The second general error, called the deterministic fallacy, is the assumption that genetic influences on our behavior take the form of genetic control of our behavior, which we can do nothing about (short of modifying our genes). The mistake in such genetic determinism is assuming or implying that genes influence behavior directly, rather than through the indirect means of working with the environment to build or modify biological structures that then, in interplay with the environment, produce behavior. Some popular books on human evolution have exhibited the deterministic fallacy by implying that one or another form of behavior—such as fighting for territories—is unavoidable because it is controlled by our genes. That implication is unreasonable even when applied to nonhuman animals. Territorial birds, for example, defend territories only when the environmental conditions are ripe for them to do so. We humans can control our environment and thereby control ourselves. We can either enhance or reduce the environmental ingredients needed for a particular behavioral tendency to develop and manifest itself.

We also can and regularly do, through conscious self-control and well-learned social habits, behave in ways that are contrary to biases built into our biology. One might even argue that our capacity for self-control is the essence of our humanity. In our evolution, we acquired that ability in a greater dose than seems apparent in any other species, perhaps because of its role in permitting us to live in complex social groups. Our capacity for self-control is part of our biological heritage, and it liberates us to some degree—but by no means completely—from that heritage.

98

Our great capacity for knowledge, including knowledge of our own biological nature, can also be a liberating force. Most evolutionary psychologists contend that an understanding of human nature, far from implying fatalism, can be a step toward human betterment. For example, in her evolutionary analysis of men’s violence against women, Barbara Smuts (1992) wrote:

Although an evolutionary analysis assumes that male aggression against women reflects selection pressures operating during our species’ evolutionary history, it in no way implies that male domination of women is genetically determined, or that frequent male aggression toward women is an immutable feature of human nature. In some societies male aggressive coercion of women is very rare, and even in societies with frequent male aggression toward women, some men do not show these behaviors. Thus, the challenge is to identify the situational factors that predispose members of a particular society toward or away from the use of sexual aggression. I argue that an evolutionary framework can be very useful in this regard. (pp. 2-3)

As you review all of the human species-typical behaviors and tendencies discussed in this chapter, you might consider how each depends on environmental conditions and is modifiable by changes in those conditions.

SECTION REVIEW

An evolutionary perspective offers functionalist explanations of aggression and helping.

Male Violence

- Male primates, including men, are generally more violent than are females of their species.

- Most aggression and violence in male primates relate directly or indirectly to sex. Genes that promote wolence are passed to offspring to the degree that they increase reproduction.

Helping

- Helping (promoting another’s survival or reproduction) takes two forms: cooperation and altruism.

- Cooperation (helping others while also helping oneself, as in the case of wolves hunting together) is easy to understand evolutionarily.

- Apparent acts of altruism (helping others at a net cost to oneself) make evolutionary sense if explained by the kin selection or reciprocity theories.

Common Fallacies

- The naturalistic fallacy, indulged in by Social Darwinists, equates what is natural with what is right.

- The deterministic fallacy is the belief that genes control behavior in ways that cannot be altered by environmental experiences or conscious decisions.