11.3 Reducing Prejudice

Racial Profiling and Immigration Video on LaunchPad

Racial Profiling and Immigration Video on LaunchPad

Reducing prejudice essentially entails changing the values and beliefs by which people live. This is tricky for a number of reasons. One is that people’s values and beliefs are often a long-

However, although there is no one-

409

Working From the Top Down: Changing the Culture

FIGURE 11.5

Brown v. Board of Education

With their historic decision in Brown v. Board of Education, the Supreme Court ruled that racially segregated schools were unconstitutional.

[Kansas State Historical Society]

The popular television show Scandal features an intelligent, high-

[Shondaland/The Kobal Collection]

Remember that prejudice exists within a cultural context, legitimized (albeit subtly at times) by the laws, customs, and norms that form the fabric of the society in which people live. Thus, one of the great challenges in reducing prejudice lies in changing these laws, customs, and norms. Often such change is made by individuals within a society, but sometimes the institutional structure can help to guide people toward this goal.

For example, when the Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education declared public-

In addition to changing the intergroup atmosphere, institutional changes can have long-

Recognizing this cycle of group images and prejudice, we see how powerfully the mass media affect how majority group members perceive minority group members. The Jeffersons in the 1970s and 1980s, Murphy Brown in the early 1990s, and Glee in 2010 were important in bringing into mainstream awareness the issues faced by African American families, single working moms, and gay teenagers. And research confirms that the more people are exposed to counterstereotypic fictional examples of minority groups (in The Jeffersons, for example, an upwardly mobile Black family), the less they show automatic activation of stereotyped associations (Blair et al., 2001; Dasgupta & Greenwald, 2001). In fact, an ambitious field experiment in Rwanda exposed people to one of two radio shows over the course of a year, either a soap opera with health messages or a soap opera with themes about reducing intergroup prejudice (Paluck, 2009). Those exposed to the show with themes about reducing prejudice showed more positive attitudes about and behavior toward interracial marriage.

410

Connecting Across a Divide: Controlling Prejudice in Intergroup Interactions

Think ABOUT

Society’s changing laws and less stereotypic popular portrayals of groups place responsibility on individuals within that society to control their biased attitudes and beliefs. Indeed, research finds that people are less likely to express their prejudice publicly if they believe that people in general will disapprove of such biases (Crandall et al., 2002). As students were faced with the reality of desegregation during the 1960s and 1970s, they were also faced with the reality of needing to control, at least to some extent, their prejudicial biases and stereotypic assumptions about outgroups. To bring it closer to home, imagine that on your first day at college you move into your dorm room and meet your roommate. He is of a different race than you are, and cultural norms and your own internal attitudes say that you should not be prejudiced. But you worry that underlying uneasiness may creep into your interactions. Will you be able to set aside any prejudices you might have and avoid stereotyping?

A Dual Process View of Prejudice

The issue of controlling prejudice takes us back to the dual process approach (Devine, 1989; Fazio, 1990), first introduced in chapter 3. In Process 1, stereotypes and biased attitudes are brought to mind quickly and automatically (through a reflexive or experiential process). In Process 2, people employ reflective or cognitive processes to regulate or control the degree to which those thoughts and attitudes affect their behavior and judgment.

Because prejudicial thoughts are often reinforced by a long history of socialization and cues in one’s environment, they can come to mind easily and be difficult to tamp down. The success of Process 2 depends on people’s motivations for controlling their thoughts. When a motivation to avoid being biased stems from an internalized goal of being nonprejudiced, people can often keep implicit biases from influencing their decisions and judgment. In many cases, though, the motivation to control prejudice stems from the perception of external pressures, such as the pressure to be politically correct or to avoid making others angry (Plant & Devine, 1998, 2009). In these cases, people may be able to control their biases, but they end up being resentful about having to censor themselves (Plant & Devine, 2001).

Given the negative consequences of extrinsically motivated efforts to suppress prejudice, how is it possible to increase people’s intrinsic motivation to control prejudice? One way is to impress on them the necessity of cooperating with those with whom they are working. When people realize they need to cooperate with an outgroup person, they can be motivated to be nonbiased in their interactions with the outgroup and even show improved memory for the unique or individual aspects of that person (Neuberg & Fiske, 1987). At some level people realize that falling back on stereotypes to form impressions might not provide the most accurate assessment of another person’s character and abilities. The need to work together on a common goal helps to cue this motivation to be accurate and allows people to set their biases aside.

More recent research has uncovered the neurological mechanisms that support these two processes (Lieberman et al., 2002). Bartholow and colleagues (2006) have examined specific electrical signals emitted from the brain that are indicative of efforts at cognitive control. They found that when White participants are presented with pictures of Black targets, the more of these signals that their brains emit, the lower the accessibility of stereotypic thoughts. However, this occurred only when people’s cognitive-

411

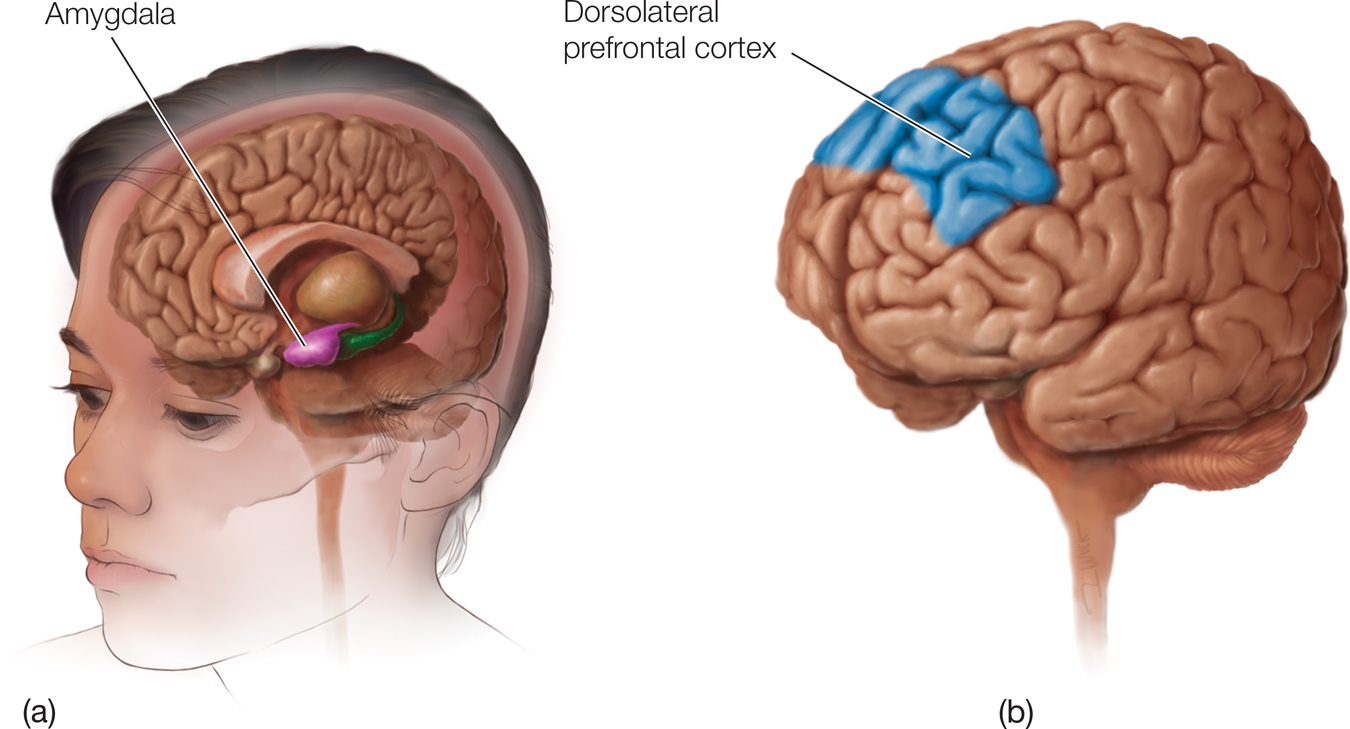

FIGURE 11.6

Downregulating Prejudice

Social neuroscience research suggests that the immediate amygdala responses (a) that Whites sometimes exhibit to Black faces can be downregulated by the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) (b).

Taking a neuroscience perspective, research shows that when White participants were exposed very briefly (for only 30 milliseconds) to pictures of Black faces, they showed increased activation in the amygdala (the fear center of the brain) to the degree that they associated “Black American” with “bad” on an implicit association test (FIGURE 11.6) (Cunningham et al., 2004; Phelps et al., 2000). With such a brief exposure, people can do little to override knee-

Prejudice Isn’t Always Easily Controlled

All of this research sounds pretty encouraging, but marshalling resources for mental control takes effort and energy. As a result, people face a few limitations when they attempt to control their biases.

The first limitation is that sometimes people make judgments of others when they are already aroused or upset. In these situations, cognitive control is impaired, so people likely will fall back on their prejudices and stereotypes. Consider, for example, a study in which White participants were asked to deliver shocks (that were not actually administered) to a White or Black confederate under the pretext of a behavior-

People also can have difficulty with regulating their automatically activated thoughts when they are pressed for time, distracted, or otherwise cognitively busy. Teachers are more likely to be biased in their evaluations of students if they have to grade essays under time pressure. If instead they have ample time to make their judgments, they are better able to set aside their biases to provide fairer assessments of students’ work (Kruglanski & Freund, 1983). People are also more capable of setting aside biases when they are most cognitively alert. This fact leads to the provocative idea that a tendency to stereotype might be affected by circadian rhythms, the individual differences in daily cycles of mental alertness which make some people rise bright and early and make others night owls. In a study of how circadian rhythms can affect jury decision making, Bodenhausen (1990) recruited participants to play the roles of jurors in an ambiguous case where the offense either was or was not stereotypical of the defendant’s group (such as a student athlete accused of cheating on an exam). Did participants allow their stereotypes of the defendant to sway their verdicts? Not if they were participating in the study during their optimal time of day. But if morning people were participating in the evening or evening people were participating early in the morning, their verdicts were strongly colored by stereotypes.

412

The Downsides of Control Strategies

Even when people succeed in controlling their biases, some downstream consequences of these efforts can be negative. First, you might recall from our discussion of ego depletion in chapter 5 (Muraven et al., 1998) that exerting mental effort in one context makes it harder to exert effort afterward in another context. For example, when White college students had any kind of conversation with a Black peer, regardless of whether the conversation was even about race, they performed more poorly on a demanding computer task right afterward than when they had this conversation with another White student (Richeson et al., 2003; Richeson & Shelton, 2003; Richeson & Trawalter, 2005). In addition, trying to push an unwanted thought out of mind often has the ironic effect of activating that thought even more. As a result, the more people try not to think of a stereotypic bias, the more it can eventually creep back in, especially when cognitive resources are limited (Follenfant & Ric, 2010; Gordijn et al., 2004; Macrae et al., 1994).

Failure of control strategies can happen even when it seems that one has gotten past initial stereotypes to appreciate the outgroup person’s individual qualities. In one study, participants who watched a video of a stigmatized student talking showed stereotype activation within the first 15 seconds, but after 12 minutes the stereotype was no longer active or guiding judgment (Kunda et al., 2002). This might seem to be good news, but not so fast. If participants later learned that the person in the video disagreed with them, the stereotype was reactivated. The implication is that, in our own interactions, we might often succeed in getting past initial stereotypes, but those stereotypes still might lurk just offstage, waiting to make an appearance if the situation prompts negative or threatening feelings toward that person.

We’ve seen that conscious efforts to control prejudice, although well intentioned, can fail or backfire completely. The implication is that reducing prejudice requires more than employing strategies to control prejudice; it also requires going to the source and changing people’s prejudicial attitudes. How do we do this?

Setting the Stage for Positive Change: The Contact Hypothesis

One strategy that seems to be an intuitive way to foster more positive intergroup attitudes is to encourage people actually to interact with those who are the targets of their prejudice. In the late 1940s and the 1950s, as American society started to break down barriers of racial segregation, some interesting effects on racial prejudice were observed. For example, the more White and Black merchant marines served together in racially mixed crews, the more positive their racial attitudes became (Brophy, 1946). Such observations suggest that if people of different groups interact, prejudice should be reduced. There is certainly some truth to this. Research on the mere exposure effect (see chapters 8 and 14) shows that familiarity does increase liking, all other things being equal.

The problem with this strategy is that only rarely are all other things equal! If you look around the world and back in history, you quickly notice countless examples of people of different groups having extensive contact—

413

In considering such questions, Allport (1954) proposed that contact between groups can reduce prejudice only if it occurs under optimal conditions. According to Allport’s original recipe, four principal ingredients are necessary for positive intergroup contact:

Equal status between groups in the situation.

Contact that is intimate and varied, allowing people to get acquainted.

Contact involving intergroup cooperation toward a superordinate goal, that is, a goal that is beyond the ability of any one group to achieve on its own.

Superordinate goal

A common problem or shared goal that groups work together to solve or achieve.

Institutional support, or contact that is approved by authority, law, or custom.

In the time since Allport laid out this recipe for reducing prejudice, hundreds of studies with thousands of participants have examined whether intergroup contact that meets these requirements can reduce prejudices based on such distinctions as race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, age, and physical and mental disabilities. These studies range from archival studies of historical situations to controlled interventions that manipulate features of the contact setting. Despite the diversity of methodologies, research generally finds that the more closely the contact meets Allport’s requirements, the more effectively it reduces a majority group’s prejudice against minorities (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006; Tropp & Pettigrew, 2005).

Prejudice Video on LaunchPad

Prejudice Video on LaunchPad

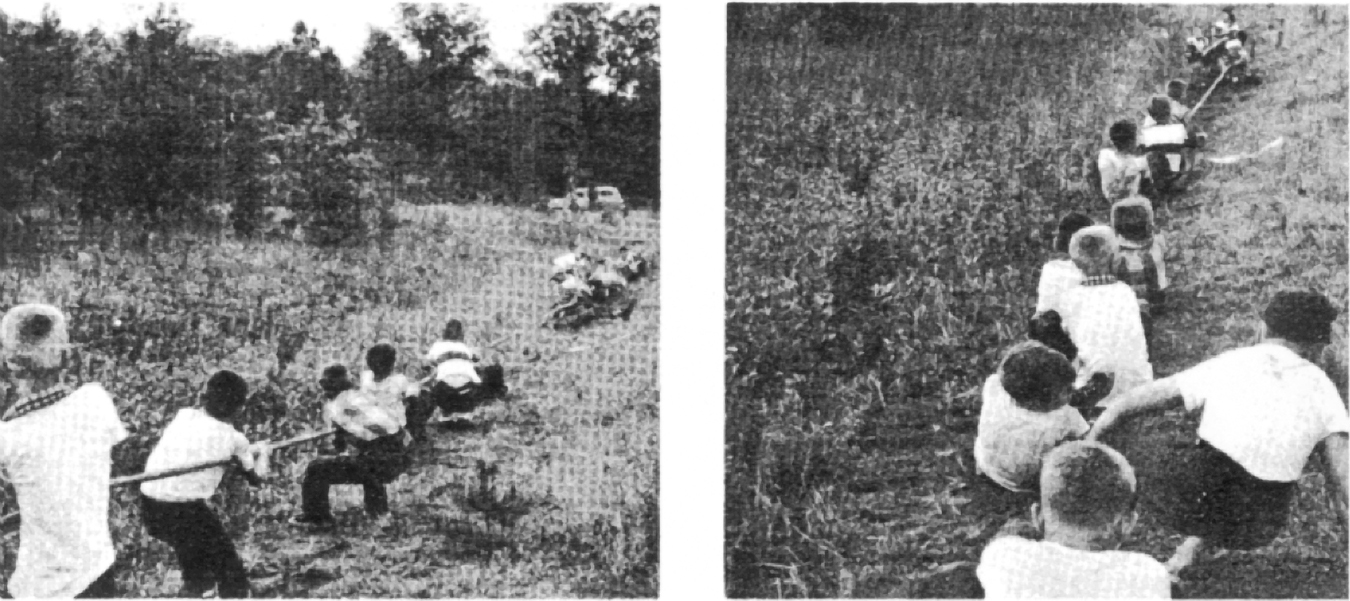

To explore one of these ingredients for change in a bit more detail, let’s explore a classic study by Sherif and colleagues (Harvey et al., 1961) that dramatically demonstrates the power of superordinate goals to reduce prejudice. In a unique study, Sherif and colleagues invited 22 psychologically healthy boys to participate in a summer camp in Oklahoma. Because the camp was at the former hideout of the noted Old West outlaw Jesse James, this study has come be known as the Robbers Cave study. As the boys arrived at the camp, Sherif assigned them to one of two groups, the “Rattlers” or the “Eagles.” During the first week, the groups were kept separate, but as soon as they learned of each other’s existence, the seeds of prejudice toward the other group began to grow (thus showing how mere categorization can breed prejudice).

In the Robbers Cave study, two groups of boys competing against each other at summer camp spontaneously developed prejudices against each other.

During the second week, Sherif set up a series of competitive tasks between the groups. As realistic group conflict theory would predict, this competition quickly generated remarkable hostility, prejudice, and even violence between the groups as they competed for scarce prizes. In the span of a few days, the groups were stealing from each other, using derogatory labels to refer to each other (calling the rival group sissies, communists, and stinkers; the study was conducted during the 1950s!), and getting into fistfights. Was all lost at the Robbers Cave?

414

It certainly appeared that way until, during the third week, Sherif introduced different types of challenges. In one of these challenges, he sabotaged the camp’s water supply by clogging the faucet of the main water tank. The camp counselors announced that there was in fact a leak and that to find the leak all 22 boys would need to search the pipes running from the reservoir to the camp. Thus, the campers were faced with a common goal that required their cooperation. As the Eagles and Rattlers collaborated on this and other such challenges, their hostilities disintegrated. They were no longer two groups warring with each other, but rather one united group working together. Successfully achieving common goals effectively reduced their prejudice.

Another way of looking at these challenges is that the Rattlers and Eagles faced a shared threat. In the example described above, it was the shared threat of going without water. Can you think of a historical example that led to a similarly cooperative spirit, only on a much grander scale? Many observers have suggested that the events of September 11, 2001, had a similar impact in reducing some types of intergroup biases in America. During and after this tragedy, the American people were confronted with the shared threat of terrorism at the hands of Osama bin Laden and al Qaeda. How did they react? In a rousing display of patriotism and goodwill, they united. Previous divisions among groups of people were set aside—

The movie Independence Day illustrates how prejudices between racial and ethnic groups can disintegrate when members of these groups are confronted by a common threat—

[20th Century Fox/The Kobal Collection/Barius, Claudette]

Research backs up the potential of shared threats to dismantle prejudices that otherwise would occur. For example, in one study testing whether people’s psychological insecurity can lead to prejudice, American participants either did or did not reflect on their mortality and then evaluated an Arab student (Pyszczynski et al., 2012). As you know from our discussions of terror management theory, thinking about death tends to increase prejudice as people cling to their own group identifications. And indeed, that occurred in this study as well. However, some of the participants were first asked to think about the worldwide implications of global warming, an environmental threat that all people face. Thinking about this shared threat reduced the effect on anti-

Why Does Optimal Contact Work?

Although the Robbers Cave experiment is usually described as an example of how superordinate goals can help break down intergroup biases, Allport’s other key ingredients for optimal contact were present as well: The boys had equal status, the cooperative activities were sanctioned by the camp counselors, and there were plenty of activities where the boys could get to know one another. But knowing that these factors reduce prejudice doesn’t tell us much about why. Other research has isolated a few key mechanisms by which optimal contact creates positive change:

Reducing stereotyping. Consider that one of the most effective forms of contact involves members of different groups exchanging intimate knowledge about each other. This allows the once-

Reducing anxiety. Optimal contact also reduces anxiety that people may have about interacting with people who are different from themselves (Stephan & Stephan, 1985). The unfamiliar can be unsettling, so by enhancing familiarity and reducing anxiety, contact helps to reduce prejudice.

Fostering empathy. Finally, optimal contact can lead someone to adopt the other person’s perspective and increase feelings of empathy. This helps people to look past group differences to see what they have in common with others.

415

When Do the Effects of Contact Generalize Beyond the Individual?

FIGURE 11.7

Stages for Intergroup Contact

Positive contact with an individual from an outgroup is most likely to generalize to the outgroup as a whole when group categorization processes are initially reduced but then reintroduced over time.

[Data source: Pettigrew (1998). Photo: mediaphotos/Getty Images]

An important question is, does contact reduce only prejudice toward that individual whom you get to know? Or do these effects generalize to that person’s group? If Frank develops a friendship with a Muslim roommate, Ahmed, during a stay at summer camp, will this contact generalize and reduce Frank’s prejudice against other Muslims when he goes back to school? Here, too, the answer is not a simple yes or no. Rather, it depends on a sequence of stages that play out over time (FIGURE 11.7) (Pettigrew, 1998; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006).

In an initial stage, as two people become friends, their sense of group boundaries melts away. Perhaps you have had this experience of talking to another person and simply forgetting that he or she is from a different group. This is decategorization at work. When sharing their love of music, Frank and Ahmed are not Christian and Muslim, they are simply two roommates and friends. Their liking for each other replaces any initial anxiety they might have felt about interacting with a member of another group.

But if Frank is to generalize his positive impression of Ahmed to other Muslims, and if Ahmed is to generalize his positive impression of Frank to other Christians, those different social categories must again become salient during a second stage, after contact has been established (Brown & Hewstone, 2005). Also, Frank’s overall impression of Muslims is more likely to change if he regards Ahmed as representative of the outgroup as a whole (Brown et al., 1999). If Frank views Ahmed as quite unlike other Muslims, then his positive feelings toward his new friend might never contribute to his broader view of Muslims. But if the category differences between them become salient and each considers the other to be representative of his religious group, then both Frank and Ahmed will develop more positive attitudes toward the respective religious outgroup more broadly.

You might be noticing a few rubs here. Effective contact seems to require getting to know an outgroup member as an individual, but this process of decategorization can prevent people from seeing that person as also being a representative of their group. There is a tension between focusing on people’s individual characteristics and recognizing the unique vantage point of their group or cultural background. But understanding others’ group identities is a key step in reducing prejudice against the group as a whole. This might be part of the reason that members of minority groups often prefer an ideology of multiculturalism, which endorses seeing the value of different cultural identities, over an ideology of being colorblind, whereby people simply pretend that group membership doesn’t exist or doesn’t matter (Plaut et al., 2009).

Another potential pitfall is that although this second stage of established contact might reduce intergroup prejudice, there is no guarantee that it will promote intergroup cooperation. For this reason, researchers have suggested that a stage of recategorizing outgroups into a unified group, or common ingroup identity, will further reduce prejudice by harnessing the biases people have in favor of their ingroups (Gaertner & Dovidio, 2000). If Frank and Ahmed see each other and other members of their respective religious groups as all part of the same camp or the same nation, then they are all in the same overarching ingroup. Perhaps this is the final dash of spice needed in the recipe of contact that will not only end intergroup prejudices but also lead to peace and cooperation.

Common ingroup identity

A recategorizing of members of two or more distinct groups into a single, overarching group.

416

Is this vision just pie in the sky? There are hopeful signs that having a common ingroup identity can effectively reduce some manifestations of prejudice. A few years ago a school district in Delaware instituted the Green Circle program for elementary school students. Over the course of a month, first and second graders in this program participated in exercises that encouraged them to think of their social world—

Although these findings are surely encouraging, Allport (1954) was skeptical about how well people can keep salient the superordinate identity of human, as opposed to more circumscribed national, regional, and family identities. For example, some theorists suggest that we are most likely to identify with groups that provide optimal distinctiveness (Brewer, 1991). Such groups are large enough to foster a sense of commonality, while small enough to allow us to feel distinct from others. Geographical differences mean different languages, customs, arts, values, styles of living—

Does Contact Increase Positive Attitudes?

It should be noted that our discussion so far has focused largely on how contact can help the majority group member foster positive intergroup attitudes toward the minority group member and his or her group. What about the other side of the coin? Does optimal contact also improve intergroup attitudes for the minority group member, such as the African American woman or the gay man put into contact with members of the majority group? A small body of research on this question shows that contact is more of a mixed bag for those in the minority (Tropp & Pettigrew, 2005). Contact situations often are framed from the perspective of reducing biases held by a majority group. The risk is that minority-

APPLICATION: Implementing Optimal Contact in a Jigsaw Classroom

|

APPLICATION: |

| Implementing Optimal Contact in a Jigsaw Classroom |

Although each of Allport’s conditions can improve racial attitudes (at least among the majority group), the best recipe for success is to combine all the ingredients in the contact setting (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006). Because the desegregation of schools seldom included all of these components for effective contact, initial evaluations of school desegregation found little success in reducing prejudice and intergroup conflict (Stephan, 1978). For example, school settings tend to emphasize competition rather than cooperation; authority figures are often mainly from the majority group so that the minority students don’t feel they have equal status; and ethnic groups often segregate within the school, minimizing the opportunity for intimate contact and cooperation.

417

FIGURE 11.8

Jigsaw Classroom

In a jigsaw classroom assignment, a lesson is divided into different subtopics, and students in diverse groups are given the assignment of mastering one subtopic. These expert groups work together to create an artifact (e.g., a joint summary or poster). Then members of each expert group return to teach their newfound knowledge to the jigsaw group, where each member has now learned a piece that makes up the larger lesson. By giving every student equal status and encouraging cooperation toward a common goal, the jigsaw classroom is an effective way to reduce prejudice.

How can schools do better? Consider a cooperative learning technique developed by Elliott Aronson and colleagues called the jigsaw classroom (FIGURE 11.8) (Aronson et al., 1978). In this approach, the teacher creates a lesson that can be broken down into several subtopics. For example, if the topic is the presidency of the United States, the subtopics might include influential presidents, how the executive branch relates to other branches of the government, how the president is elected, and so on. The class is also subdivided into racially mixed groups where one person in each group is given the responsibility of learning one of the subtopics of the lesson. This student meets with other students from other groups assigned to that subtopic so that they can all review, study, and become an expert in that topic, creating some kind of artifact such as a poster or a presentation to summarize their newly gained knowledge. The experts then return to their original group and take turns teaching the others what they have learned.

The power of this approach is its potential for embodying all of Allport’s conditions for optimal contact. First, because the task is assigned by the teacher, it is authority sanctioned. Second, because each student is in charge of his or her own subtopic, all the kids become experts, and thus have equal status. Third, the group is graded both individually (recall our discussion from chapter 9 on accountability and social loafing) and as a group. Thus, the students share a common goal. And fourth, to do well and reach that common goal, they must cooperate in intimate and varied ways, both teaching and learning from each other. All the pieces must fit together, like the pieces in a jigsaw puzzle.

The jigsaw classroom program is generally successful, so much so that one wonders why it is not implemented more widely. One reason is that some topics in school may not lend themselves to this kind of learning approach, but still, a lot do. Compared with children in traditional classrooms, children who go through the program show increased self-

418

Reducing Prejudice Without Contact

Eye of the Storm I Video on LaunchPad

Eye of the Storm I Video on LaunchPad

As we’ve just seen, Allport provided us with an excellent playbook for reducing intergroup prejudices through positive and cooperative contact. But sometimes people hold prejudices about groups with which they never interact. When the opportunities for contact are infrequent, can other psychological strategies reduce intergroup biases? The answer is yes.

Perspective Taking and Empathy

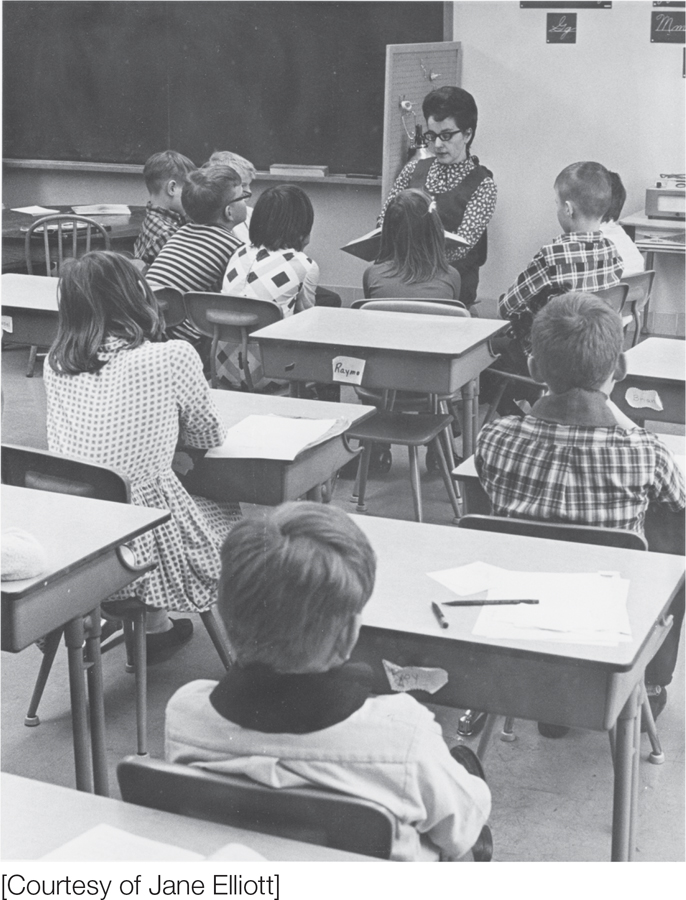

In the aftermath of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Jane Elliott taught her third-

[Courtesy of Jane Elliott]

Earlier, we mentioned that one of the reasons optimal contact can be so effective is that it creates opportunities to take the perspective of members of the other group and see the world through their eyes. Direct contact isn’t the only way for people to learn this lesson. To see why, let’s go back in time to 1968, just a few days after Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated. Jane Elliott, a third-

Over the next couple of days, she divided the class into two groups, those that had brown eyes and those that had blue eyes. She spent one day defining one group as the privileged and the other as the downtrodden. These designations were reflected in her actions and demeanor to the class, telling them, for example, that brown-

What Elliott observed from this and subsequent implementations of the exercise was a remarkable, and apparently enduring, sensitivity to prejudice. Her students became acutely aware of the harmful effects that their own prejudices could have (see Peters & Cobb, 1985). It is powerful stuff, and we encourage you to search the Internet (Google or YouTube “Jane Elliott” plus “A Class Divided”) to check out some video clips. In having her third graders spend a day being stigmatized for the color of their eyes, Jane Elliott implemented an impressive exercise in perspective taking.

Perspective taking is a powerful tool for reducing prejudice, because it increases empathy for the target’s situation and creates a sense of connection between oneself and an outgroup. This strategy reduces prejudice against a single individual, and those positive feelings are often likely to generalize to other members of the outgroup (Dovidio et al., 2004; Galinsky & Moskowitz, 2000; Vescio et al., 2003; Vorauer & Sasaki, 2009). For example, in one study, participants who were asked to imagine vividly the experiences of a young woman who had been diagnosed with AIDS (as opposed to taking a more objective viewpoint toward her plight) felt more empathy for AIDS victims in general as well as for her (Batson et al., 1997).

Eye of the Storm II Video on LaunchPad

Eye of the Storm II Video on LaunchPad

The success of perspective taking is impressive. It seems to work not only for more explicit types of prejudice but also for the more implicit and subtle forms of bias we described earlier. For example, imagine that you are White and that you are asked to write about a day in the life of a young Black man (Todd et al., 2011). If you were in the perspective-

419

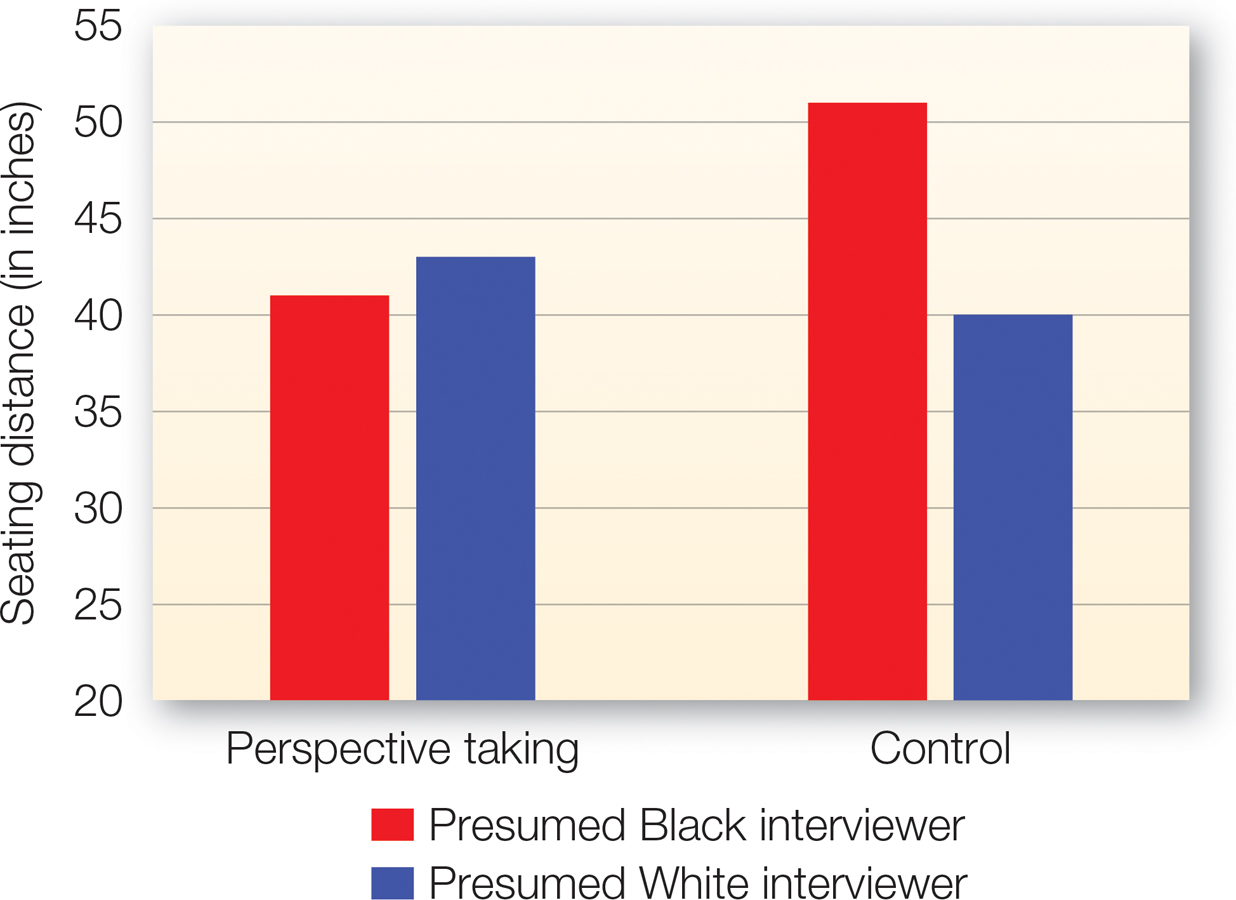

FIGURE 11.9

Reducing Prejudice With Perspective Taking

Although White participants in a control condition chose to keep their distance from a Black interviewer, after having vividly imagined the day in the life of a young Black man, this implicit form of bias was eliminated.

[Data source: Todd et al. (2011)]

Unknown to you, and to the participants who actually were in this study, the researchers measured the distance between the two chairs as an implicit measure of prejudice. They reasoned that if people had a more positive attitude toward the interviewer, they would set the chairs closer together. As you can see in FIGURE 11.9, participants in the control condition elected to sit farther away from Tyrone than from Jake. But if they first had to take the perspective of another young Black man during the earlier task, they sat at the same distance from the assistant regardless of his race. When we think about what it’s like to walk a day in the life of someone else, our biases are often diminished. In fact, in one very clever study conducted in Barcelona, Spain, researchers used virtual reality to have light-

Reducing Prejudice by Bolstering the Self

Perspective taking reduces prejudice by changing the way people think about others. But can we also reduce prejudice by changing how people think about themselves? Because some prejudices result from people’s deep-

You may recall a couple of theories suggesting that people take on negative attitudes toward others to protect their positive view of themselves. For example, according to terror management theory (Solomon et al., 1991), when a person encounters someone else who holds a very different cultural worldview, it can threaten the belief system that upholds his or her sense of personal value, which can increase fears about death. When people feel that their self-

Research shows that bolstering self-

Self-

420

Although bolstering a person’s self-

Reducing Prejudice with a More Multicultural Ideology

Part of why bolstering how people see themselves reduces prejudice is because it makes people more open minded and less defensive (Sherman & Cohen, 2006). This leads us to consider perhaps a more straightforward strategy for reducing prejudice: reminding people of their tolerant values. Making such values salient can indeed have positive effects (e.g., Greenberg et al., 1992).

One way of encouraging tolerance is conveyed as an effort to embrace a colorblind ideology, which views people only on their individual merits, avoiding any judgment based on group membership. One concern with the colorblind approach is that it encourages efforts simply to control any biases or prejudices that one has toward an outgroup. Although this can sometimes be an effective way to avoid engaging in discrimination, our earlier discussion of controlling prejudice revealed that these efforts can also backfire.

Colorblind ideology

The idea that group identities should be ignored and that people should be judged solely on their individual merits, thereby avoiding any judgment based on group membership.

SOCIAL PSYCH at the MOVIES

Remember the Titans

Remember the Titans

Capturing the complexities of racial integration on film is no easy feat. Many movies tackle themes of racial prejudice, but the 2000 film Remember the Titans (Bruckheimer & Yakin, 2000) provides what might be the best cinematic example of how to reduce prejudice by applying Allport’s formula for successful intergroup contact. This movie is based on the true story of separate high schools in Alexandria, Virginia that were forced to merge in 1971 as part of a rather delayed effort to desegregate Virginia’s public schools. Integrating the student body also meant integrating the football teams, and the movie chronicles the growing pains of this newly diversified group and its struggle to put together a winning season.

The film centers around the head coach of the Titans, Herman Boone, played by Denzel Washington, who faces an uphill battle in training a unified team of White and Black players who previously attended separate schools, played on rival teams, and still hold deeply entrenched racial prejudices. The film clearly depicts the conflict on the football field as a microcosm of the conflict in American culture in the immediate aftermath of the civil rights movement. The movie just as effectively portrays how Coach Boone pulls his team together to clinch the state championship in 1971.

Recall that one of the elements for effective intergroup contact is the presence of institutional support. In the movie, this support is established at the outset when the school board decides to give the head coaching job to the former coach of the Black high school rather than to the coach of the White high school (played by Will Patton). This decision sends a clear message to the players and their parents that the school board has good intentions to integrate not only the school and the athletic programs but also the staff. Although tensions occasionally flare among the coaches, they generally work together for successful integration.

The second element for effective contact is establishing equal status. Coach Boone makes his hard-

Still, the players themselves struggle to get past their mistrust of one another. Seeing how his team continues to default to self-

Does this strategy of forcing players to room together work? Not at first. A White player objects to his Black roommate’s iconic poster of the track and field champions Tommie Smith and John Carlos giving the raised-

Remember the Titans shows these important components of contact at work. If any of these components were missing, do you think that T. C. Williams High School still would have won the state championship in 1971? Why or why not? What lessons can we learn for creating more effective integration today?

421

Another criticism of the colorblind approach is that it can imply that everyone should conform to the status quo and act as if ethnic differences don’t matter. As we alluded to above, the colorblind approach is a much more comfortable stance for the advantaged majority group than for currently disadvantaged minority groups. Allport’s original formulation of the contact hypothesis largely adopted a colorblind approach. More recent research reveals that Whites in the United States tend to take this to the extreme, sometimes failing to mention a person’s race, even when doing so is simply stating a descriptive fact about an individual that could help describe the person to whom they are referring (Apfelbaum et al., 2008; Norton et al., 2006).

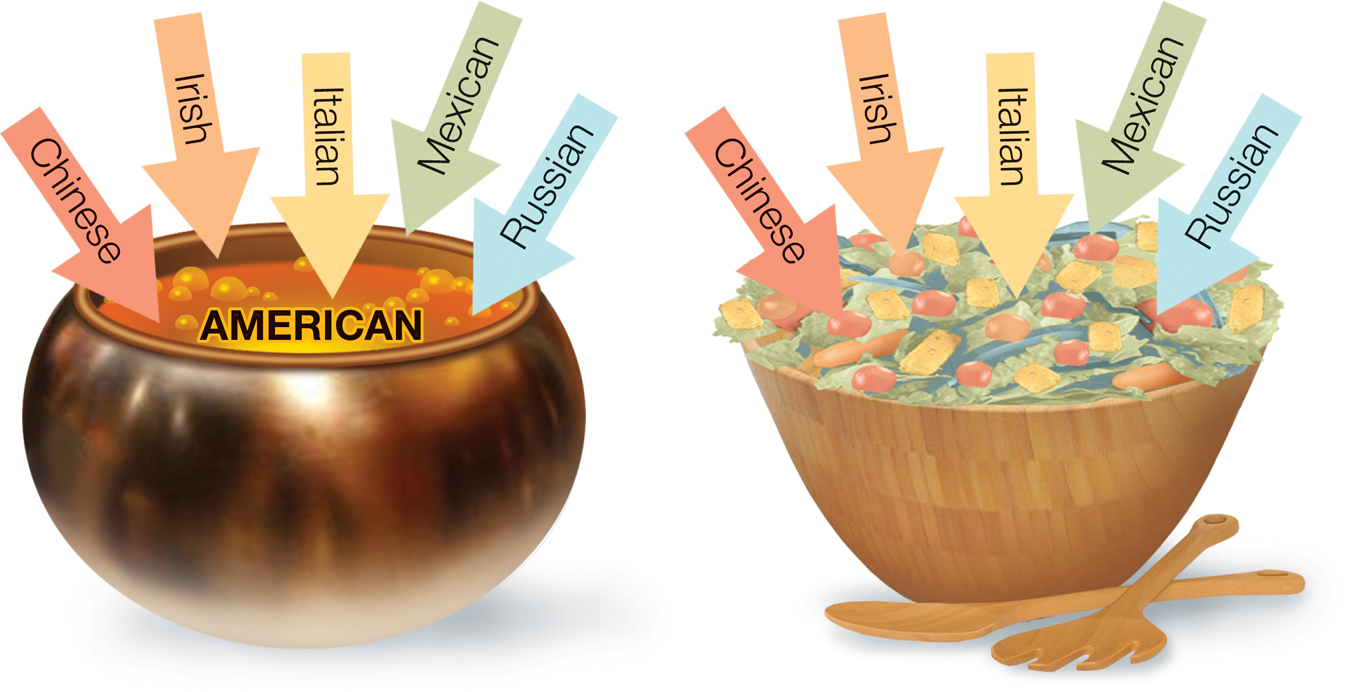

An alternative is to embrace cultural pluralism, or a multicultural ideology, which acknowledges and appreciates different cultural viewpoints. This view emphasizes not just tolerating but actively embracing diversity. To understand the distinction between these two ideologies, consider the metaphors used in the United States and Canada, two countries that were formed largely as a result of immigration. The United States is typically referred to as a melting pot, a place where people of different ethnicities and former nationalities might converge and blend to form a single group. In Canada, the prevailing metaphor is the salad bowl, where citizens form an integrated collective while still maintaining their distinct ethnic heritage.

Multicultural ideology

A worldview in which different cultural identities and viewpoints are acknowledged and appreciated.

Diversity can be described through metaphor. The melting pot depicts a colorblind approach, whereas the salad bowl emphasizes multiculturalism.

422

From a psychological perspective, these different ideologies suggest different ways of approaching intergroup relations. A colorblind approach suggests that we should avoid focusing on group identity, whereas multiculturalism suggests that we should approach group differences as something to be celebrated. Going into an interaction with a multicultural mind-

In a clever application of this same idea, Kerry Kawakami and her colleagues (Kawakami et al., 2007) showed that these approach tendencies can be trained quite subtly. In one of their studies, participants completed an initial task in which they simply had to pull a joystick toward them when they saw the word approach displayed on a screen or push it away from them when they saw the word avoid. Unknown to the participants, faces were subliminally presented just before the target words appeared. Some individuals always were shown a Black face when they were cued to approach; others were shown a Black face when they were cued to avoid. After completing this task, participants had an unconscious association to approach or avoid Blacks. When they were asked to engage in an interracial interaction with a Black confederate, those in the approach condition behaved in a more friendly and open way than those in the avoid condition. These results show that our goals for interactions can be cued and created unconsciously as well as consciously and that an approach orientation toward diverse others can be quite beneficial.

Although these findings are encouraging, embracing diversity is not without its challenges. Promoting diversity also makes salient both group categories and differences between groups. And in cultural-

Final Thoughts

Social psychology has taught us a lot, not just about where prejudice comes from and how it is activated but also about how it can be reduced. Yes, there is a long and varied list of cures, but that’s because bias has many different causes and manifestations. Although our interest in being egalitarian can motivate us to control our biases, the bottom line is that seeking out common ground and understanding while also embracing the value of different viewpoints and perspectives may be the most effective way of achieving intergroup harmony.

However, encouraging tolerance assumes that people want to be tolerant. This is where broader changes in cultural norms can play a powerful role in helping people internalize these motivations. The more we see others behave and interact in an egalitarian way, the more we follow suit. Reducing prejudice doesn’t happen overnight. All of us will suffer relapses on the way, but cultures can shift gradually toward equality. Reducing prejudice against a segment of the population can benefit everyone in the end. For example, cross-

423

SECTION review: Reducing Prejudice

|

Reducing Prejudice |

|

Prejudice has no single cause. Various strategies are available to reduce it. |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Changing the culture Long- |

Controlling prejudice in interactions Individuals can prevent their automatically activated prejudices from affecting their behavior. However, controlling prejudice is not always easy and can backfire. |

The contact hypothesis According to Allport’s conditions, optimal intergroup contact can reduce prejudice when it establishes equal status. enables people to become acquainted with outgroup members. encourages cooperation toward superordinate goals. is sanctioned by authorities. Optimal contact reduces stereotyping. decreases intergroup anxiety. increases empathy for the outgroup. Acknowledging both subgroup and superordinate identities can allow positive effects of contact to generalize. Allport’s optimal conditions for contact can reduce intergroup biases more for members of the majority than for the minority group. The jigsaw classroom is an application of optimal contact to education. |

Reducing prejudice without contact Perspective taking increases empathy and decreases negative stereotypes. Bolstering people’s good feelings about themselves helps them feel less threatened by those who hold differing views. Multiculturalism is perhaps the most effective ideology for reducing biases held by the majority while also valuing diverse perspectives held by minority groups. |

CONNECT ONLINE:

Check out our videos and additional resources located at: www.macmillanhighered.com/