1.5 Ethical Considerations in Research

The ultimate goal of psychological research is to advance our understanding of the human condition in order to make life better for people, so we certainly wouldn’t want to undermine the quality of life for the participants in our research. Accordingly, social psychologists devote considerable attention to ethical concerns. Because many of the issues of interest to social psychologists pertain to the dark and distressing side of human nature and behavior, social psychologists are compelled to include these unpleasant aspects of existence in their research. To study fear, it is often necessary to make people afraid; to study egotism and prejudice, people must be put in situations where these unbecoming characteristics become manifest. Social psychologists must continually ask whether the value of the research findings is worth the distress or discomfort that participants might experience because of their studies.

Harming Research Participants

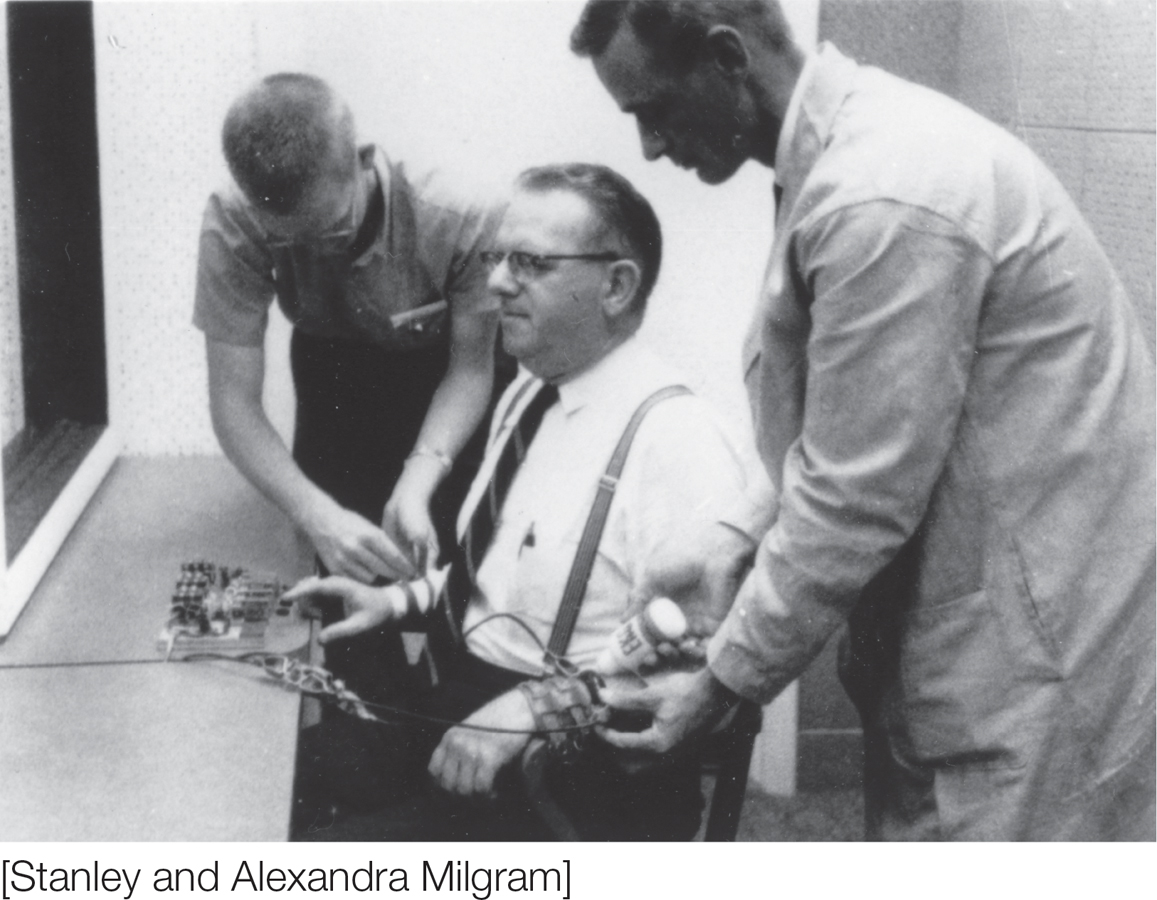

The Milgram studies sparked a debate about ethics in social psychological research.

[Stanley and Alexandra Milgram]

Obviously, some practices are ethically unacceptable under any circumstances. Clear examples of inhumane treatment that could never be justified under any circumstances are the horrible experiments conducted by Nazi Germany in the concentration camps during World War II: studying the behavioral and psychological effects of starvation and freezing; infecting children with hepatitis to learn how the liver functions; injecting pregnant women with toxic substances to refine abortion and sterilization techniques (Lifton, 1986). The Tuskegee syphilis experiment, conducted between 1932 and 1972 by the United States Health Service, in which African Americans infected with syphilis were not told that they had the disease and were not given penicillin in order to study the progression of the disease was also heinous (Jones, 1981). In general, anything that could cause permanent, long-

But what about experiments that produce temporary discomfort and stress? Perhaps Milgram’s (1974) classic studies of obedience to authority, in which participants believed they were giving a middle-

Debate about the ethics of the Milgram studies will probably continue for years, and we will discuss these studies in greater detail in chapter 7. Currently, the American Psychological Association (APA) does not allow researchers at American colleges to replicate these studies exactly as they were originally done. At the same time, the results of these studies are considered highly valuable and are taught in virtually every college in North America and in those of many other countries as well. Whether the value of what we learned about obedience to authority outweighed the risks to participants is ultimately a personal judgment that we must all make for ourselves. Regardless of where you stand on this issue, the Milgram research illustrates the conflict that social psychologists often face when deciding whether their research is ethically acceptable.

34

Deceiving Research Participants

Another ethical issue of particular concern to social psychologists is the use of deception in research. Social psychologists often mislead the participants in their studies about the true purpose of their research. They do this to create the psychological states they wish to study. Indeed, social psychologists use deception in their research more than any other scientists do. In his obedience studies, Milgram told participants they were in a study of learning and that their role was to deliver increasingly high voltage electric shocks to another participant with a heart condition. In fact, the purpose of the study was to investigate obedience; no shocks were actually delivered, and the apparently suffering “other participant” was a confederate of the experimenter acting according to a prearranged script. This was a powerful deception, and as already noted, one that many people believe stepped beyond ethical bounds.

Most social psychological experiments involve some level of deception, but the vast majority of these studies use relatively minor deception by offering a cover story, an explanation of the purpose of the study that is different from the true purpose. Many of the studies we will be discussing have gone further than that, though. Some researchers have staged emergencies, told participants they did poorly on intelligence tests, frustrated participants, threatened them with electric shocks, and given them false information about their personalities.

Cover story

An explanation of the purpose of the study that is different from the true purpose.

There are two primary reasons for the use of deception in social psychological research. First, if participants know the true purpose of the research, their responses are likely to be affected by their knowledge of that purpose. But participants need not even be accurate in their suspicions about the purposes of a study for those suspicions to taint the study’s findings. A substantial body of research has shown that if people know (or think they know) the purpose of a study, it puts a demand on them to behave in a certain way (Orne, 1962). For example, if people knew the purpose of Milgram’s research, they probably would have disobeyed very quickly. Aspects of a study that give away a purpose of the study are called demand characteristics. Studies with demand characteristics are inconclusive because the possibility that the participants were affected by their knowledge of the purpose introduces an alternative explanation for the results of the study. One source of demand characteristics can be an experimenter’s expectations of how participants are supposed to behave. As we noted, researchers are people with their own desires and biases, and these can affect how they treat participants even if the researchers are not aware of it. This is known as experimenter bias. To eliminate this bias whenever possible, experiments should be designed so that the researchers are “blind” to experimental conditions; that is, they won’t know which condition a particular subject is in. That way there is no way for them to systematically treat any participant differently depending on what condition the participant is in.

Demand characteristics

Aspects of a study that give away its purpose or communicate how the participant is expected to behave.

Experimenter bias

The possibility that the experimenter’s knowledge of the condition a particular participant is in could affect her behavior toward the participant and thereby introduce a confounding variable to the independent variable manipulation.

Second, researchers often use deception to create the conditions necessary to test a hypothesis. For example, if the hypothesis is that frustration leads to aggression, a social psychologist might manipulate level of frustration and then measure aggression to test this hypothesis. The manipulation of the independent variable, frustration, would require staging some sort of frustrating experience. For example, one study (Geen, 1968) tested the frustration-

Think ABOUT

Although it is clear that deception is a useful practice for conducting research, the question remains whether this kind of deliberate misrepresentation is justified or not. Some argue that deception is never defensible because it betrays the trust that should exist between the researcher and the research participant. Others argue that deception often is the only way to study many important psychological states and that the knowledge gained through the use of deception in research justifies the potential distress. Where do you stand? We, like the vast majority of social psychologists, embrace the latter position. So do the APA and other legal and professional organizations that govern research in the countries where social psychology flourishes.

35

Ethical Safeguards

To provide guidance on these matters, the APA established a Code of Ethics that all psychological researchers in the United States must abide by. First, the ethical implications of all studies must be carefully considered and approved, both by the investigators conducting the research and by ethical review boards at their institutions. These ethical review boards judge whether the potential benefits of the research outweigh the research’s potential costs and risks to the participants. Second, participants must give their informed consent to take part in any study, after they are provided with a full disclosure of all the procedures they are to undergo and the potential risks that participation might entail. Participants must also have the right to ask questions and to withdraw from the study at any time, even after the study begins. Finally, participants must be assured that the information they provide will be treated confidentially, that adequate steps will be taken to protect their confidentiality, and that their identities will not in any way be linked to their responses without their explicit consent.

These safeguards are very important, but when deception is used, the informed consent cannot be fully informing. To minimize any potential negative effects of deception, at the conclusion of a study experimenters conduct a debriefing. In this debriefing, the experimenter probes for suspicion about the true purpose of the study, gently reveals any deceptions, clarifies the true purpose of the study, and explains why the deception was necessary to achieve the goals of the research. For example, in Milgram’s studies of obedience, all participants were fully debriefed, and many were quite relieved to meet and shake hands with the person whom they believed they had been shocking. When properly done, the debriefing should be informative, comforting, and educational, not only alleviating any negative feelings and misconceptions the participant had about the study or their actions in the study, but also providing a peek behind the curtain of social psychological research. Research shows that properly done debriefings do indeed achieve these goals (Sharpe & Faye, 2009).

Debriefing

At the end of a study, the procedure in which participants are assessed for suspicion and then receive a gentle explanation of the true nature of the study in a manner that counteracts any negative effects of the study experience.

SECTION review: Ethical Considerations in Research

|

Ethical Considerations in Research |

|

Any research involving human participants must be conducted in accordance with ethical principles based on a cost- |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Harm No lasting physical or psychological harm must be caused. |

Deception The use of deception must be justified in any study and its potential for any harm minimized. |

Ethical Safeguards The APA has established a Code of Ethics. An ethical review board assesses whether each study meets these ethical standards. Informed consent is an important protection, though limited in studies using deception. Debriefings that are reassuring and educational are crucial to ensure the ethicality of deception research. |

CONNECT ONLINE:

Check out our videos and additional resources located at: www.macmillanhighered.com/