3.4 Returning to the “Why”: Motivational Factors in Social Cognition and Behavior

So far, we have focused on the automatic processes involved in how we perceive people and events in the environment. We have not said too much about motivation. This doesn’t mean that motivational factors have little influence on when, what, and how we apply schemas to our understanding of the world. As we noted at the outset of this chapter, motivational factors are linked to cognitive processes. They are the engine that puts this cognitive machinery into action (Kruglanski, 1996; Kunda, 1990; Pyszczynski & Greenberg, 1987b).

110

Priming and Motivation

To see how motivation plays a role, think back to the study in which people primed with rudeness were quicker to interrupt an experimenter’s conversation (Bargh et al., 1996). Did the prime directly trigger the rude behavior? Probably not. In that study, participants were motivated from the outset to get the experimenter’s attention, so although the prime increased their tendency to interrupt a conversation, it did not trigger the behavior without some motivation to engage in it. Other research more directly reveals that primed ideas influence thought and behavior, particularly when they are compatible with the person’s preexisting motivation. For example, subliminally priming the idea thirst can lead a person to drink more, but only when that person is thirsty; without this motivation to satisfy thirst, the prime has no effect on beverage consumption (Strahan et al., 2002).

Priming helps people prepare to act. When primed with the concept of “elderly,” for example, people who have positive attitudes toward older adults walk more slowly, perhaps because doing so would allow them to interact with an elderly person more easily.

[Lisa F. Young/Shutterstock]

In addition, because our motivations are intertwined with many of the objects, events, and people we encounter, priming such contexts and cues often activates specific motives and goals that are associated with them (Gollwitzer & Bargh, 2005). If we’re looking for someone to date and we see an attractive person, this motivation activates not only schemas pertaining to beauty but also the goal of meeting that person.

Cesario and colleagues (Cesario et al., 2006) illustrated this point using a priming procedure developed by Bargh and associates (1996). In the original study, participants had to rearrange sets of scrambled words to form grammatical sentences. Embedded within this sentence-

However, Cesario and colleagues argued that being exposed to the prime didn’t just make the elderly schema accessible but also activated participants’ feelings about and motivation to interact with elderly individuals. Some people have positive attitudes about old people, and others have more negative attitudes. For those who have positive attitudes toward the elderly, when the elderly schema is activated, so too is the motivation to interact positively with such people. These participants might unconsciously adjust their behavior to have a smoother interaction with an elderly person; this could include walking more slowly, as Bargh and his team had shown.

But when the same schema is primed for those who have negative attitudes toward the elderly, so too is the motivation to avoid them. Therefore, the researchers hypothesized, these participants should walk faster to avoid the elderly and leave them in the dust. This was exactly what they found. When participants had positive attitudes about the elderly, they responded to the elderly prime by walking more slowly. However, when participants had negative attitudes about the elderly, they responded to the prime by walking faster! These results support the point that primes do not influence behavior in a simple manner, but rather interact with the person’s motivation to determine what she or he thinks and does in a given context (Cesario et al., 2010).

111

Motivated Social Cognition

Clearly, people are not simply automatons, blindly controlled by whatever schemas happen to be accessible in their minds. Indeed, the tools that we use to think serve our needs and goals. As a result, we do not think about the world “out there” as though we were video cameras; rather, our everyday thinking is significantly shaped by the motives and needs that we have in the moment. What are those motives and needs? Some stem from our bodies, of course. A hungry person is more likely to think about food than sex and will likely look for, and notice, a restaurant faster than an attractive person who happens to be walking by.

Other motives have to do with the kinds of thoughts we want to have about the people, ideas, and events that we encounter in our social environment. Specifically, what we think about, and how we think about it, are continually influenced by three psychological motives that we introduced earlier in this chapter: to be accurate, to be certain, and to maintain particular beliefs and attitudes that fit with our worldview (Kruglanski, 1980, 2004). These motives are constantly at work, sometimes below our conscious radar, filtering which bits of information get into our minds, how we interpret and remember them, and which we bring to mind to justify what we want to believe.

For one, the motive for accuracy can lead people to set aside their schemas and focus on the objective facts. For example, when a person is motivated to understand who another person really is, perhaps because he is going to work with her on a task, he may be motivated to look past the convenient stereotypes he has for her group and put more thought into her individual personality (Fiske & Neuberg, 1990).

What about the need for nonspecific closure? When people are motivated to gain a clear, simple understanding of their surroundings, they tend to see events in a way that wraps up the world in a neat little package. We mentioned at the beginning of the chapter that this need can become active when the situation makes thinking unpleasant. In a study demonstrating this motivation for nonspecific closure (Kruglanski & Freund, 1983), participants told that they had to form an impression of someone in a limited amount of time tended to reach a conclusion based on the first bits of information they received, failing to take into account relevant information that they encountered later (known as the primacy effect). In contrast, participants not under time pressure felt more comfortable considering all the relevant information before reaching a conclusion about what the person was like.

Mental laziness is not the only reason people seek closure on simple, consistent interpretations of the world. Sure, sometimes thinking takes effort and so we stick to familiar, simple conclusions. Yet another benefit of maintaining well-

Why, deep down, are inconsistent states of mind threatening? From the existential perspective, maintaining clear, simple interpretations of reality provides people with a psychological buffer against the threatening awareness of their mortality (Landau et al., 2004) and a broader sense of meaning (Heine et al., 2006). If the world appears fragmented, chaotic, or vague, people may have difficulty sustaining faith that there is anything bigger than themselves—

112

Let’s turn to the need for specific closure. In many cases, people want more than mere certainty: they want to reach conclusions that support their preferred views of the social world, including events, other people, and themselves. Mac users want to think Macs are better than PCs; most people want to believe their country is great; and we all want to think our friends are good people. In the sections above we reviewed a number of research studies that demonstrate the ways in which people filter and manipulate reality in order to maintain their preferred beliefs and attitudes.

Let’s consider one more example of such motivated social cognition: how people interpret an athletic event when they attach their feelings of self-

SOCIAL PSYCH at the MOVIES

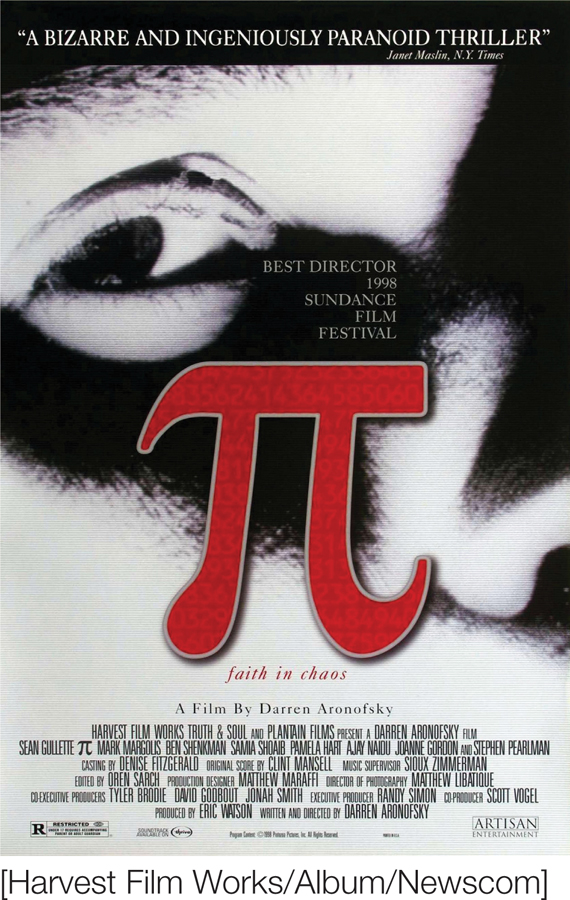

Pi

Pi

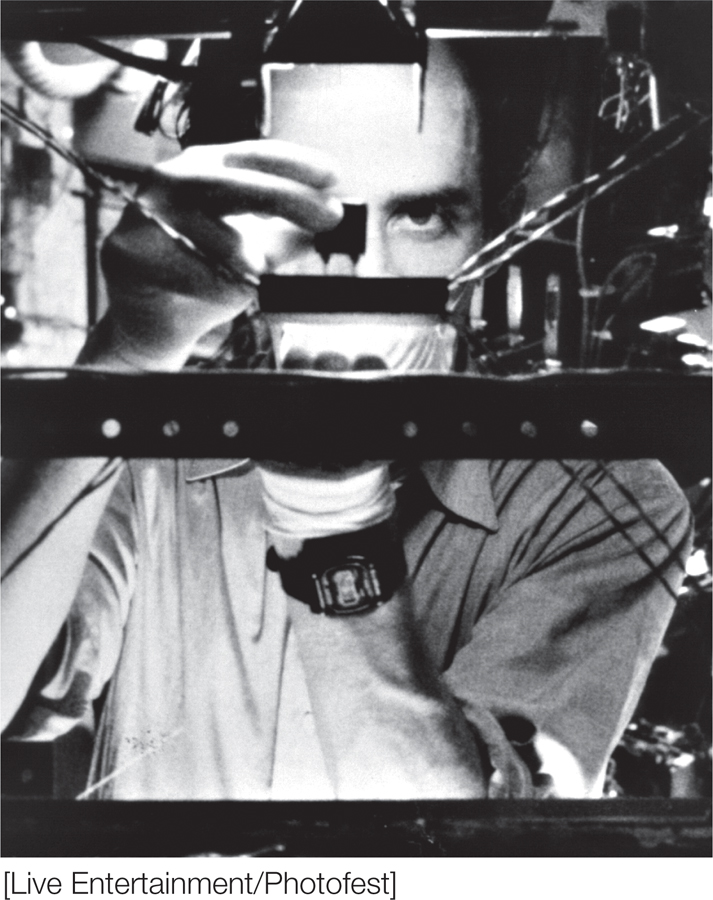

π (Pi), a surrealist psychological thriller directed by Darren Aronofsky and released in 1998 (Watson & Aronofsky, 1998), dramatically illustrates schemas’ power over people’s lives. The movie centers on Max Cohen (Sean Gullette), a genius mathematician who lives like a hermit in his apartment, into which he’s crammed a sprawling, home-

For the past 10 years, Max has been trying to uncover the hidden numerical pattern beneath the stock market, a notoriously chaotic system. Max’s supercomputer crashes under the strain of his research, but the answer it spits out just before crashing—

Let’s focus on three aspects of Max’s life that connect with ours, albeit usually in less extreme forms.

Max sees elusive mathematical patterns everywhere. For him, they pop out of the environment, just as faces or a vase can pop out of FIGURE 3.1. For example, when we see a city street through Max’s eyes, passersby appear as a jittery, undifferentiated mass of bodies, whereas the stock market numbers displayed on a building’s LCD monitor are crystal clear. Later, when Max becomes obsessed with spirals (a representation of the mysterious Golden Ratio in math), he sees them in his coffee, the newspaper, and the smoke rolling off a cigarette. He is hunting for order in nature, and he sees it everywhere . . . or does he?

Sol Robeson (Mark Margolis), Max’s elderly mentor and only friend, warns Max about his obsession: “You have to slow down. You’re losing it. . . . Listen to yourself. You want to find the number 216 in the world, you will be able to find it everywhere. Two hundred and sixteen steps from your street corner to your front door. Two hundred and sixteen seconds you spend riding on the elevator. When your mind becomes obsessed with anything, you will filter everything else out and find that thing everywhere!”

Max’s search for mathematical order highlights some aspects of reality and obscures others. The rest of us may not be so fanatical, yet we all use schemas to filter our perception of the social world.

[Live Entertainment/Photofest]

Max is clearly extreme in the way he filters reality through his schemas, but even supposedly normal people like the rest of us prefer interpretations of reality that confirm our schemas. As we’ve seen, this is the confirmation bias. Perhaps the only difference is that Max’s schemas are idiosyncratic: No one else seems to share them—

Just as powerfully as Max’s schemas make some features of the environment salient, they downplay whatever does not fit within his precise mathematical worldview. When Max is approached by Devi (Samia Shoaib), his friendly neighbor bearing gifts and offering affection, he resists her. Why? For one thing, Max lacks a script for interacting with others—

that is, he lacks knowledge of how the give- and- take of normal social interactions unfolds in time. As a result, social interactions are too uncertain and unpredictable for him to manage; hence, they end awkwardly.

But looking deeper, we also see the self-

Finally, Max’s character illustrates a simple but important point: People do not simply like order; they actually need order because they are threatened by the opposite: disorder and chaos. Sol tries to convince Max that the world is extremely complex and chaotic, but Max’s search for order is unrelenting. Driven by purpose, he becomes more restless, disheveled, and paranoid. He is beset with debilitating migraine headaches, hallucinations, and blackout attacks.

Is Max that different from the rest of us? As we’ve noted in this chapter, people certainly differ in how much they prefer well-

When people watch competitive sports, their interpretation of controversial plays and penalties is often biased by which team they want to win.

[AP Photo/Mel Evans]

113

Consistent with your likely intuition, a study of fans’ impressions of a particularly rough football game between Princeton University and Dartmouth College back in 1951 indicates that they would not. Following the game, Albert Hastorf and Hadley Cantril (1954) showed students from both schools a film of it and then asked them how many penalties each team had committed. Princeton students saw Dartmouth players committing many more penalties than Princeton players, whereas Dartmouth students saw their team only commit half the number of penalties that the Princeton students attributed to them. But of course, students from both schools watched the same film! Our motivations—

114

Since this classic study, researchers across the globe have shown in myriad studies the many ways in which people’s cognitions are biased by their motivation to maintain preferred beliefs and attitudes. Of course, there are limits to the influence of motives on people’s thinking. For people to function effectively in the world, their cognitions must be generally accurate representations of external and social reality. If one’s favorite college basketball team doesn’t win a game all season, believing they are the best team in the nation would be too discrepant with reality and therefore unsustainable. One would have to also believe in a mass conspiracy or that everyone else was crazy. As a result, the person’s understanding of reality is the product of a compromise among three motivations: desire to be accurate, to be certain, and to hold on to valued beliefs (Heine et al., 2006; Kunda, 1990).

Mood and Social Judgment

In addition to psychological motives, moods can play an important role in shaping social judgment about a given event or person. A mood is a generalized state of affect that persists longer than the experience of an emotion. For example, the happiness a person experiences after finding a dollar bill on the ground lasts a couple of minutes, but moods can continue to resonate for much longer. This points to another unique characteristic of moods: Unlike with emotions, often the person does not know why she or he is in a given mood. Sometimes we just find ourselves feeling bad or good, and we cannot quite put our finger on why.

Think ABOUT

Why might humans have evolved the ability to experience moods in the first place? For one thing, moods may inform the person about the status of things in the immediate environment. Think about this from the evolutionary perspective. Being in a positive mood is a signal that everything is okay, that there are no immediate threats to be concerned with. Negative moods, on the other hand, signal that something is wrong and might be deserving of one’s attention. In fact, over the course of our species’ evolution, positive moods might have promoted exploring the environment, expanding hunting territories, and trying unfamiliar foods—

By this logic, mood states should affect both the content of a person’s social judgments and how motivated the person is to engage in effortful processing of information. If people are feeling good while considering whether they like a person or an event such as a party, they are more likely to view each of them positively. If they are feeling lousy, that will color their view of such things negatively. Also, the more thought people put into such judgments, the more their moods color them (Forgas, 1995). The reason is that the more thinking a person does, the more his mood infuses his evaluations of the various aspects of the person or event he is evaluating.

Mood also affects how motivated people are to think extensively about people and events occurring around them. Because positive moods signal that things are okay, individuals feeling good rely on more heuristic or automatic forms of processing when making judgments about people, events, and issues (Bless et al., 1996; Forgas, 1998; Mackie & Worth, 1989). In other words, they rely more on the experiential system of cognition that we introduced at the beginning of this chapter. For instance, people in good moods are more likely to rely on stereotypes when judging people (Bodenhausen et al., 1994).

115

On the other hand, negative moods tell the person that something is wrong. Therefore they lead the person to think more carefully to figure out what is bothering her. Studies show, in fact, that participants experiencing a negative mood focus on relevant details before making a judgment, rather than settling on a quick and dirty judgment (Bless et al., 1990; Forgas et al., 2005; Gasper & Clore, 2002).

As a demonstration of this idea, Herbert Bless and his colleagues (Bless et al., 1990) had students recall a very happy or a very sad event in their lives, a manipulation that reliably induces a positive or negative mood. In a supposedly unrelated study, participants listened to an essay that argued for an increase in student fees at the university. For half of the sample, the arguments in the essay were rather weak, but for the other half, the arguments in the essay were quite strong—

Our intuition might lead us to think that if a friend is in a bad mood, it is not a good time to try to change her opinion on some issue. However, according to this line of research, if your arguments are strong, it is actually the best time to do so!

The Next Step Toward Understanding Social Understanding

In this chapter, we focused primarily on how we process and are affected by information as it unfolds—

SECTION review: Returning to the “Why”

|

Returning to the “Why” |

|

Motivation plays a role in shaping which schemas are activated as well as when and how those schemas affect behavior and judgment. |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Primed ideas influence thinking and behavior when they are compatible with the person’s preexisting motivation. |

The three psychological motives introduced in the first part of this chapter— |

Mood affects how motivated we will be to expend effort on processing information. |

CONNECT ONLINE:

Check out our videos and additional resources located at: www.macmillanhighered.com/