4.1 Remembering Things Past

When we try to figure out who was at fault in a fender bender, we rely on basic ways of making sense of the world.

[Yellow Dog Productions/Getty Images]

To make sense of the world, we count on our ability to remember events, people, and objects that we have encountered in the past. Through the use of our senses, we take in information from the world around us. Imagine hearing the fire alarm going off in your building. You look out into the hallway, and see people rushing from their rooms. In the case of an actual fire, you might also smell the acrid odor of smoke, taste the salty flavor of sweat on your upper lip as you hurry through the heat, and feel your way along a darkened stairwell to navigate to the outside world. Each of your senses is providing you with information to help you understand the situation and engage in the appropriate behavior. In this situation, it’s quite clear how these sensory processes help us to perceive the demands of the situation (fire!) and engage in a certain sequence of behaviors that accomplishes an important goal (escape!). But we don’t just perceive and then act. We are also equipped with the important ability to lay down traces of memory that allow us to build a record of things that have happened in the past.

This record of memory is really quite useful. Not only does it help us make sense of the world we’re currently experiencing but it also allows us to learn from past experience so that we might better predict what will happen in the future. In our everyday understanding of memory, we think about memories as the past record of personal experiences that we have had (that time when I narrowly escaped a burning building) or information we have learned (when you spray an aerosol can of cooking spray at a lit barbecue, it acts like a flame thrower). But memory is really much more than that; in fact, there are different types of memory, and a sequence of processes that underlie how memories get formed and are recalled. Let’s consider how memories are formed so we can then understand how they are influenced by various social factors.

How Are Memories Formed?

Studying for a test is one of those rare occasions where we actively try to store information in memory, but most of the time laying down memories happens automatically, with little effort on our part. How does this process of memory formation happen?

First, we can make a distinction between short-

Short-term memory

Information and input that is currently activated.

Long-term memory

Information from past experience that may or may not be currently activated.

When you are at a party, embarrassed by the fact that you cannot for the life of you remember the name of your roommate’s significant other, you can take some comfort in knowing that there are a lot of places where the process of remembering can break down. Maybe your roommate never mentioned the name (lack of sensory information to begin with), or perhaps you were very distracted when the name was mentioned (lack of attention needed to encode sensory information). Even if you were paying attention, you might not have been motivated to consolidate the name into long-

119

How Do We Remember?

Retrieving information from long-

In trying to gather this information together, we may intend to seek accurate knowledge. But the need for closure, and the tendency to reach conclusions that fit with what we expect or desire, often crash the party. Indeed, among the more potent tools that we use to reconstruct our memories are our schemas. As you might expect from our discussion of schemas in chapter 3, when we try to recall information about an event, our schemas guide what comes to mind. Just as an investigator could be biased in the search for evidence (e.g., interviewing only observers likely to support an early interpretation of the events), we often remember information that matches our preexisting schemas, and we ignore or discount information that conflicts with our schemas.

Memory for Schema-Consistent and Inconsistent Information

In one study illustrating how schemas shape memory (Cohen, 1981), participants watched a videotape of a woman they believed was a librarian or a waitress. The woman in the videotape explained that she liked beer and classical music. When participants were later asked what they remembered about the woman, those who believed she was a librarian were more likely to recall that she liked classical music. Those who believed she was a waitress were more likely to remember that she liked beer. The reason for this difference is that the schema of the woman led the participants to look for, and therefore tend to find and encode into long-

Although most of the time we find it easier to remember information that is consistent with our schemas, sometimes information that is highly inconsistent with one of our schemas also can be very memorable (Hamilton et al., 1989). Such information is often attention grabbing and forces us to think about how to make sense of it. If you go to a funeral and someone starts tap-

Whether schema-

However, if the discrepant information grabs our attention, and we have the resources to think about it, then inconsistent new information is likely to be especially memorable. If you have a generally proper and reserved grandmother, and one time she had a few too many margaritas at a wedding and started dancing wildly with a stranger, you’d probably remember that quite well (unless your resources were also quite limited, perhaps by sharing in said margaritas).

120

Our discussion so far concerns what happens when we try to recall information about which we have a preexisting schema. The story is quite different if our schema emerges only later on, after we’ve been exposed to a particular piece of information. If you take in specific information about a person or event and then are given a particular schema about it afterward, the memory is primarily consistent with the new schema, and recall of the memory reinforces the new schema.

In a study assessing the effects of schemas that develop both before and after learning specific information about a person, participants were asked to listen to an audiotape of 36 events in the life of a female college student (Pyszczynski et al., 1987). The events included some positive and some negative social behaviors on her part (e.g., “irons her roommate’s skirt for her”; “criticizes her boyfriend”). However, either before or after listening to the tape, participants were given background information that created a strong schema of the student that was either positive (including such traits as modesty and kindness to others) or negative (conceit and contempt for others). Participants were later asked to recall information from the list of events that they heard.

When the schema came before the list of behaviors, participants mainly recalled behaviors that were highly inconsistent with the schema. For example, if participants had initially formed a negative schema about the person, they easily remembered that person’s positive behaviors. This fits the idea presented earlier that when information is highly inconsistent with our schemas, we tend to process it more thoroughly and encode it into memory. However, if the strong general schema was formed after the listing of behaviors, participants were better able to recall those events that were consistent with the positive or negative schemas they had formed. For example, forming a negative schema after hearing the list of behaviors improved memory for negative behaviors. Because these participants did not have a schema when they were initially presented with the person’s behavior, the inconsistent behaviors did not seem inconsistent at the time of encoding and thus were not processed more thoroughly. But after exposure, when participants were given a schema to work with, that schema helped to guide their recall of the behaviors that were consistent with that schema.

This last finding demonstrates that how we think about things now (our current schemas) is a potent guide to what we recall from the past. Another study (McFarland & Ross, 1987) demonstrated how present experiences can create expectations that guide our recollections. For the sake of illustration, let’s imagine the participants Frank and Mike, each of whom has just started a dating a new partner. In the study, Frank and Mike are asked how in love they are at the beginning of their relationships. Both indicate being moderately in love. Then, two months later, Frank and Mike are questioned again. This time they are asked how in love they currently are with their partners, but also how in love they had been during the initial stages of their relationship.

Note that this second round of questioning allows the researchers to compare Frank’s and Mike’s memories of how in love they were with their actual ratings two months earlier. As it turns out, Mike’s relationship has been going quite well, and he reports being very much in love with his partner. Frank, on the other hand, is now having lukewarm feelings. What about their memories of their initial feelings of love? Mike’s estimates of how in love he was two months ago are now higher than Frank’s, even though back then they were equally in love with their partners. This is exactly the pattern of results that the actual study found with real participants. Our present perceptions can create a schema that biases how we recall (or actually, reconstruct) events from the past.

Although a schema can color memory in either a positive or negative light, people have a general tendency to show a rosy recollection bias and to remember events more positively than they actually were (Mitchell et al., 1997). This is especially true if people feel positively about their current experience. More broadly, people tend to exhibit mood-

121

One caveat to keep in mind during our discussion of this tendency to attend to and remember schema-

The Misinformation Effect

Misinformation effect

The process by which cues that are given after an event can plant false information into memory.

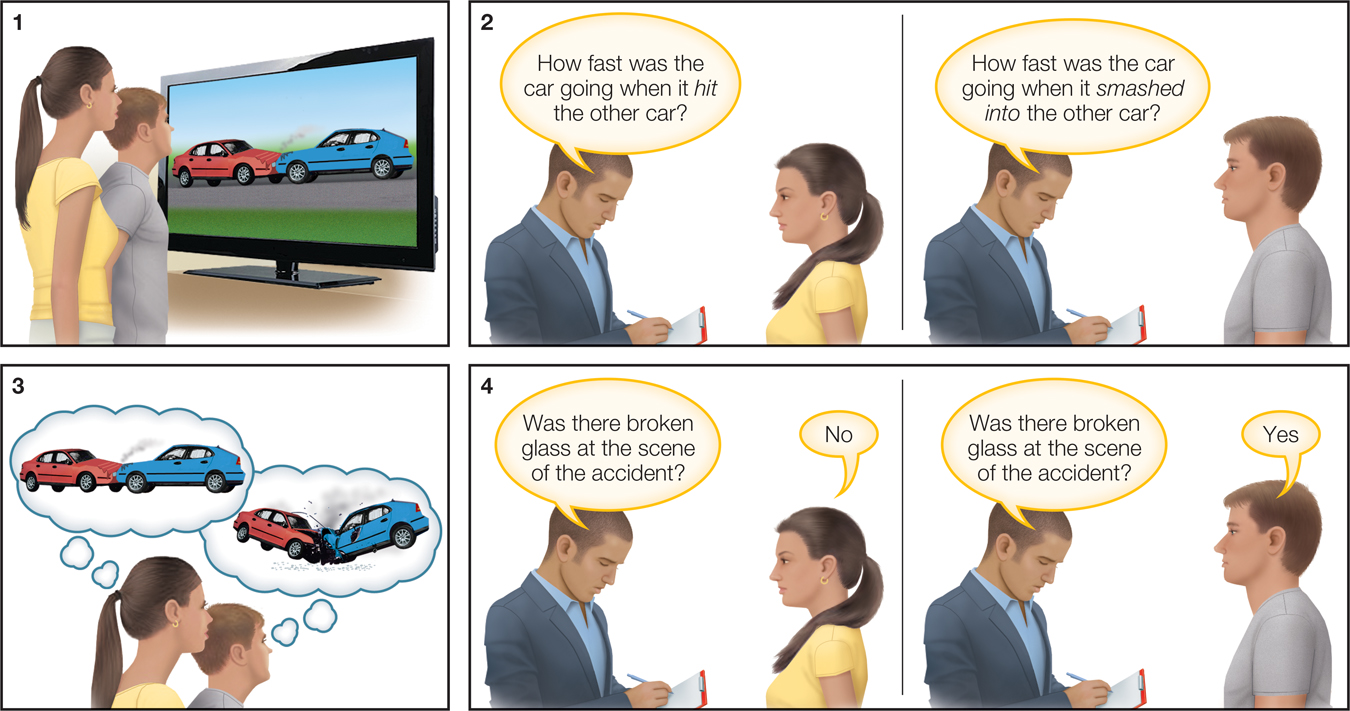

FIGURE 4.1

Misinformation Effect

Loftus and her colleagues illustrated how the phrasing of a question can lead someone to remember seeing something, like broken glass, that actually wasn’t there.

Clearly our memories are biased by our current way of understanding the world. Sometimes these biases can even lead us to remember things that didn’t actually happen. The process is best captured by Elizabeth Loftus’s work on the misinformation effect. The misinformation effect is the process by which cues that are given after an event can plant false information into memory. In a classic study by Loftus and colleagues (1978), all participants watched the same video depicting a car accident (FIGURE 4.1). After watching, some participants were asked, “How fast was the car going when it hit the other car?” Other participants were asked, “How fast was the car going when it smashed into the other car?” You might not be surprised to learn that participants asked the question with the word smashed estimated that the car was going faster than did participants who were asked the question with the word hit. Even a simple word such as smashed can prime a schema for a severe car accident that rewrites our memory of what happened in the video.

Misinformation effect

The process by which cues that are given after an event can plant false information into memory.

122

Perhaps more interesting, however, is what happened when participants were later asked if there was broken glass at the scene of the accident. Those participants who had earlier been exposed to the word smashed were more than twice as likely to say “yes” than were participants previously exposed to the word hit (even though there was no broken glass at the scene). Thus, this study illustrates how our memories can be susceptible to misinformation. The way in which the question was asked created an expectation that led people to remember something that actually was not there!

APPLICATION: Eyewitness Testimony

|

APPLICATION: |

| Eyewitness Testimony |

Eyewitness Testimony Video on LaunchPad

Eyewitness Testimony Video on LaunchPad

Similarly, vigorous debate continues about repressed memories of childhood sexual abuse. Although unfortunately, such abuse surely does occur, some researchers have suggested that some reports of such memories “recovered” during psychotherapy sessions (often involving hypnosis) may be false. How could this happen? Such dramatic reconstruction in memory may be possible because of a combination of a few different factors. First, the person who is led to believe that such events happened generally might be someone who is more susceptible than most to suggestion. Second, the person has sought help from a therapist presumably because he or she is suffering from psychological difficulties and is motivated to understand and get past those problems. Third, the person may find him-

123

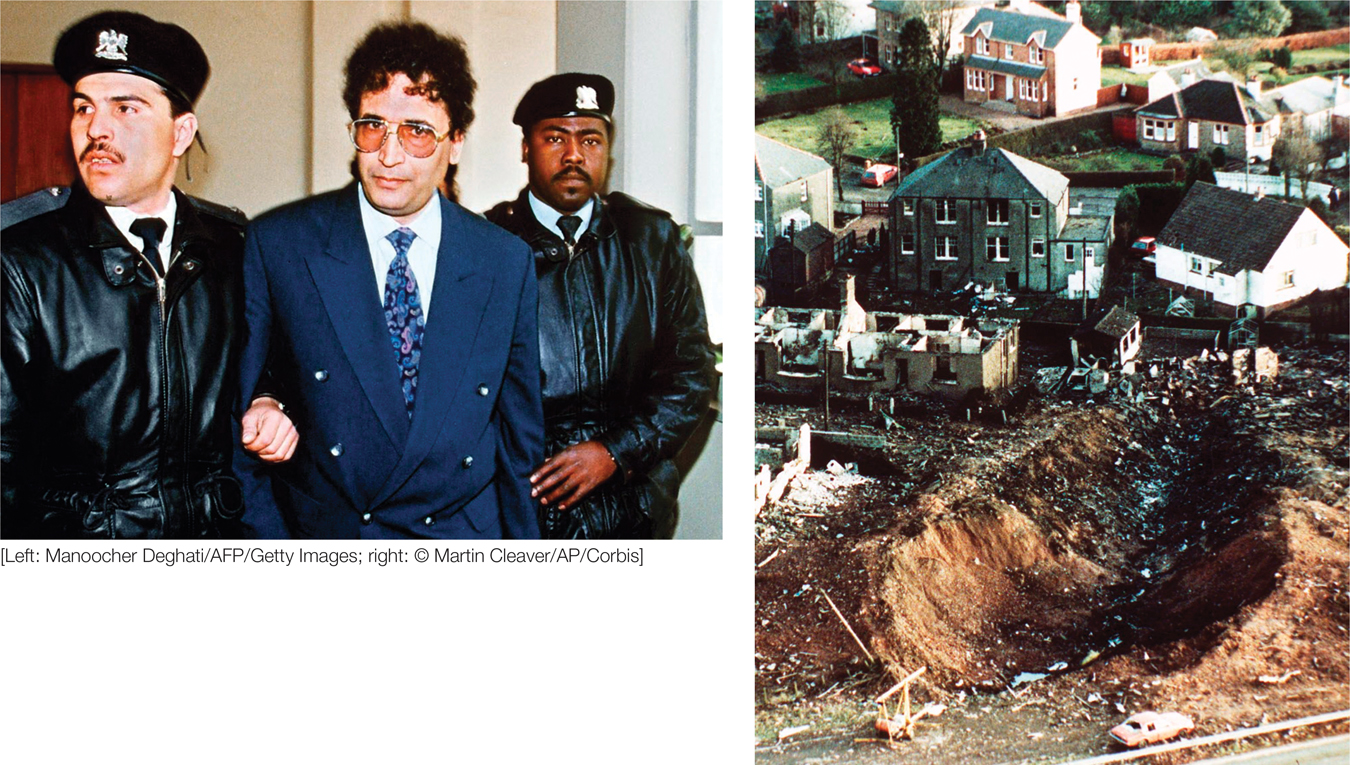

FIGURE 4.2

Al–

[Left: Manoocher Deghati/AFP/Getty Images; right: © Martin Cleaver/AP/Corbis]

The misinformation effect demonstrates not just how the metaphorical investigator in our head becomes biased in its interpretive processes but also how real-

Jerry Sandusky (the coach on the right) faced charges of sexually preying on adolescent boys. Sometimes the schemas we have of how certain people are supposed to act don’t mesh with how they are accused of acting.

[Centre Daily Times/MCT via GettyImages]

In contrast, there is clear evidence that childhood sexual abuse does occur, as the highly publicized scandals in the Catholic Church and at Penn State University demonstrated. All reported memories of such abuse should be taken very seriously. Although it is conceivable that such shocking events could be falsely recalled, it seems more likely that real memories of such horrific experiences will be dismissed because they don’t fit the schema most of us have of how adults—

The Availability Heuristic and Ease of Retrieval

Clearly, the content of the memories people recall, whether true or false, greatly influences their judgments. But people’s judgments can also be affected by how readily memories can be brought into consciousness. Try to make the following judgment as quickly as possible. Which of the two word fragments listed below could be completed by more words?

(1) __ __ __ __ I N G or (2) __ __ __ __ __ N __

If your first inclination was to choose option 1, you just exhibited what is referred to as the availability heuristic (Tversky & Kahneman, 1973). This is our tendency to assume that information that comes easily to mind (or is readily available) is more frequent or common. It’s relatively easy to think of four letter words that you can add “ing” to, but it is more of a struggle to come up with seven-

Availability heuristic

The tendency to assume that information that comes easily to mind (or is readily available) is more frequent or common.

The availability heuristic has the power to distort many of our judgments. If you were planning to visit Israel, you would probably be worried about possible suicide bombings. When such attacks occur, they make the news. But actually, Israel has a very high fatality rate from car accidents, so that, when in Israel, you are far more likely to die in a car accident than in a suicide bombing. Similarly, people generally are more afraid of flying in an airplane than of driving their car, yet according to the National Safety Council (2014), the lifetime risk of dying in a motor vehicle accident is 1 in 112, whereas the lifetime risk of dying during air travel is 1 in 8,357. But every airplane accident attracts national media attention, whereas most car fatalities are barely covered at all. Because airplane crashes are so easily recalled, using the availability heuristic makes it seem that they are more prevalent than they really are. If the media covered each of the safe landings or each fatal car accident with as much intensity, the airline industry would probably enjoy a large increase in ticket sales!

124

Inspired by research on the availability heuristic, Norbert Schwarz and colleagues (1991) discovered a related phenomenon known as the ease of retrieval effect. With the availability heuristic, people rely on what they can most readily retrieve from memory to judge the frequency of events. With the ease of retrieval effect, people judge how frequently an event occurs on the basis of how easily they can retrieve a certain number of instances of that event. To demonstrate this, Schwarz and colleagues asked college students to recall either 6 instances when they acted assertively or 12 instances when they acted assertively. You might expect that the more assertive behaviors you remember, the more assertive you feel. But the researchers found the exact opposite pattern: participants asked to recall 12 instances of assertiveness rated themselves as less assertive than those asked only to recall 6 instances. Take a few moments and try to think about 12 distinct times when you behaved assertively. If you are like most people, coming up with 12 distinct episodes is actually pretty difficult, much more difficult than only recalling 6 times. So what do people draw from the process of doing this task? People seem to make the following inference: If I’m finding it difficult to complete the task that is asked of me (recalling 12 acts of assertiveness), then I must not act assertively much, and so I must not be a very assertive person. Some studies suggest that this ease of retrieval effect occurs only if the person puts considerable cognitive effort into trying to retrieve the requested number of instances of the behavior (e.g., Tormala et al., 2002). Only then do they attend to the ease or difficulty of retrieval and use it to assess how common the recalled behavior is.

Ease of retrieval effect

Process whereby people judge how frequently an event occurs on the basis of how easily they can retrieve examples of that event.

APPLICATION: What Is Your Risk of Disease?

|

APPLICATION: |

| What Is Your Risk of Disease? |

Much as we might like to think that people objectively determine their estimated risk for disease by considering their actual risk factors, this is not always the case. Peoples’ judgments about health risk are strongly influenced by many of the cognitive and motivational factors covered throughout this textbook. One factor is the ease with which people can recall information that makes them feel more or less vulnerable. For example, the ease of retrieval effect we have been describing also occurs in judgments of the risk of getting HIV and other health risks (e.g., Raghubir & Menon, 1998). The more easily students could recall behaviors that increase risk of sexually transmitted diseases, regardless of the number of actual risk behaviors they remembered, the more at risk they felt. Similarly, asking participants to recall three behaviors that increase the risk of heart disease increased judgments of perceived risk more than did asking them to recall eight such behaviors (Rothman & Schwarz, 1998).

But there is an important caveat here as well as reason for optimism that, at least in certain situations, we will adopt a more thoughtful approach to estimating risk. When Rothman and Schwarz (1998) asked participants who had a family history of heart disease, and thus for whom the condition was quite relevant, to think of personal behaviors that increase risk, they estimated themselves to be at higher risk when asked to come up with more, rather than fewer, risky behaviors. This suggests that with greater personal relevance, people’s judgments are less reliant on an ease of retrieval effect.

125

SECTION review: Remembering Things Past

|

Remembering Things Past |

|

We rely on our memory to make sense of the world. |

|

|---|---|

|

Forming Memories |

Remembering |

|

Memories are formed when we encode information and consolidate it into long- |

Our memories are often reconstructions rather than objective facts and are subject to bias. These reconstructed memories are influenced by our schemas, which generally guide us to remember information that is consistent with the most salient schema. The misinformation effect is an example of reconstructed memory, because leading questions plant expectations that influence us to remember events differently than they actually occurred. We often base our judgments on how readily information comes to mind (the availability heuristic) and the ease with which we can retrieve it. |