5.4 Self-regulatory Challenges

What factors make self-

Willpower: Running Hot and Cool

One of the keys to effective self-

Walter Mischel and various colleagues have been studying willpower over the last 40 years (Mischel & Ayduk, 2004). To understand how people successfully use willpower to self-

If you ever thought that some people seem to have more willpower than others, you were right. Mischel and Ebbesen (1970) studied people’s varying abilities to use their cool system to overrule their hot system, working with children as young as four years old. The core idea was to pit an attractive short-

178

SOCIAL PSYCH out in the WORLD

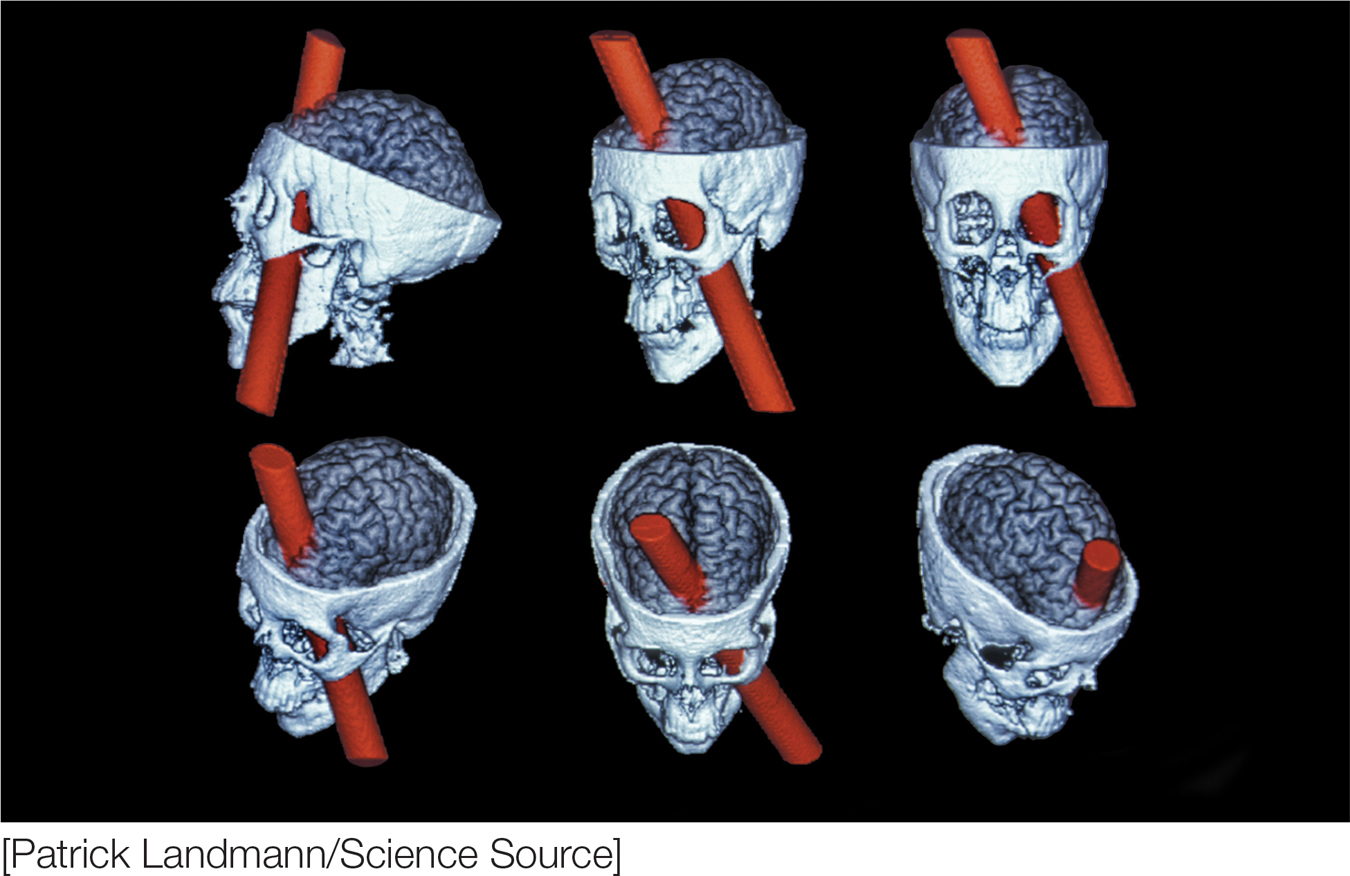

Neurological Underpinnings of Self-

Neurological Underpinnings of Self-

It was in the late summer of 1848 that Phineas Gage was busy laying railroad track in Vermont, a job that required drilling a hole in a rock and filling it with explosive powder, then running a fuse to it and covering the powder with densely packed sand (Fleischman, 2002). Gage had a custom-

With a doctor’s help, the wound eventually healed, but the reason Gage’s case has become so interesting to psychologists is that his personality changed in very specific ways. Although Gage’s intellectual capacities were essentially intact and his motor functioning unimpaired, his personality was radically transformed. Before the accident, Gage had a reputation as an honest, hard-

There are a couple of lessons we can take away from the case of Phineas Gage. One of the big lessons is that the brain is involved not only in the way we move our limbs and process visual information but also in those aspects of our self and personality that make us who we are, including the choices we make, the impression we give to others, and the future plans that we form to give our lives coherence and meaning.

Let’s take a closer look at some of these brain areas. Gage’s case offers exciting clues about one of the specific brain regions responsible for self-

The ventromedial prefrontal cortex is just one of the regions that are important to social and emotional aspects of self-

The orbitofrontal cortex is an area that lies just behind the eye sockets. Jennifer Beer and colleagues (2003) have examined how damage to the orbitofrontal cortex impairs people’s ability to regulate their social behavior. Imagine that you are a participant in a study and asked to come up with a nickname for the experimenter, whose initials, you are told, are L.E. If you are a middle-

179

This seemingly simple task actually relied on some complex mental processes. You had to generate meaningful word pairs that allowed you to achieve your goal of seeming clever but that also satisfied the goal of remaining within the bounds of social decorum. If a sexual response springs to mind, your social monitoring system flags it as inappropriate, and it is consciously suppressed.

But what would happen if your social monitoring system were damaged—

The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) is not an anatomical structure but rather an area of the frontal lobes that is responsible for many executive functions. For example, it is involved in planning, inhibition, and regulation of behavior toward an abstract goal (Banfield et al., 2004). As you might imagine, people with damage to this area have difficulty carrying out even simple everyday tasks (Shallice & Burgess, 1991). Consider the case of one frontal-

The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) (Banfield et al., 2004). This region lies on the medial (inner) surface of the frontal lobes and interacts with areas of the prefrontal cortex. One primary function of the ACC is to signal when some behavior or outcome is at odds with your goals. The ACC helps draw your attention to conflicts between what you want and what has just happened. It then communicates with the DLPFC, which steps in to switch plans or change behavior to get you back on track.

Cunningham and colleagues (2004) looked at how the ACC and the DLPFC allow people to monitor and regulate their social biases. Cunningham presented White participants with pictures of White and Black faces and neutral gray squares while he scanned their brain activity using functional magnetic resonance imagery (fMRI), a technique that provides information about activity in the brain when people perform certain cognitive or motor tasks. Some of the pictures were presented very quickly (30 ms) so that he could capture people’s immediate and automatic affective response, and some were presented more slowly (525 ms) so that people would have time potentially to regulate whatever their immediate reaction had been. What did Cunningham find? First, patterns of neurological activity showed increased activation in the amygdala, a region implicated in fear processing, when people were presented very quickly with a Black as opposed to a White face. This neurological signature of an automatic fear response was particularly strong for participants with more negative implicit racial biases. When people had a bit longer to look at a Black face, they showed increased activation in both the ACC and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, but no longer showed increased amygdala activation. The level of ACC and DLPFC activity was the strongest for those people who had not only strong implicit biases but also the goal of being nonprejudiced. The implication is that after an initial fear response, the ACC in these individuals might have signaled that this was not the response they wanted to have to Blacks, and perhaps their DLPFC kicked in to reduce and regulate that immediate, knee-

Functional magnetic resonance imagery (fMRI)

A scanning technique that provides information about the activity of regions of the brain when people perform certain cognitive or motor tasks.

Although research that links neurological processes to social behaviors is still in its infancy, results such as these are beginning to shed light on the complex array of cognitive systems that are involved in helping us formulate, enact, monitor, and follow through on our goals and intentions.

180

In an amazing finding, performance on this delay of gratification task at age four predicts a variety of indicators of self-

These findings paint a fairly fatalistic picture, but the ceiling on one’s capacity for willpower is not entirely fixed early in life. Generally, factors that keep the cool system active help the person delay gratification. But beware the factors that block the cool system and activate the hot system, such as high levels of stress, being under cognitive load (Hamilton et al., 2007; Hull & Slone, 2004; Metcalfe & Mischel, 1999), alcohol and other recreational drugs, and exposure to temptations such as cookies fresh out of the oven.

Does this mean that we should focus only on our cold process and disregard our hot desire for long-

Trying Too Hard: Ironic Process Theory

Think ABOUT

Sometimes, something in a situation brings to mind thoughts that distract us from what we are trying to do. When unwanted thoughts absorb our attention, we often try to shift focus away from these thoughts and back onto the tasks that more directly relate to the central goal of the day (such as mastering statistics). As agents with free will, we should find this a piece of cake, right? Surely, I should have some say over what I think about! However, mind control—

How did you do? Perhaps this task wasn’t too difficult, and you were able to focus your attention elsewhere. Many people, however, are surprised to discover that even though they try to keep white bears out of consciousness, the bears keep popping up. This is an example of what Dan Wegner (1994) calls ironic processing, whereby the more we try not to think about something, the more those thoughts enter our mind and distract us from other things. In laboratory studies, students who first spent five minutes trying to suppress thoughts of white bears reported having more than twice as many thoughts of white bears by the end of a subsequent five-

Ironic processing

The idea that the more we try not to think about something, the more those thoughts enter our mind and distract us from other things.

181

Yet we are continually trying to suppress thoughts. But how do we do it, and why is it often so difficult? Wegner (1994) describes two mental processes that we use to control our thoughts. One process acts as a monitor that is on the lookout for signs of the unwanted thought; in order to do such monitoring, such thoughts must be accessible, that is, close to consciousness. The second process is an operator that actively pushes any signs of the unwanted thought out of consciousness. The best way to do this is through distraction, filling consciousness with thoughts of other things.

Monitor

The mental process that is on the lookout for signs of unwanted thoughts.

Operator

The mental process that actively pushes any signs of the unwanted thoughts out of consciousness.

When asked to suppress a thought, people can generally employ these two processes and suppress successfully. However, once people stop trying to suppress the thought, typically a rebound effect occurs: The unwanted thought becomes even more accessible than it was before suppression. Although there is still some debate about the cause of this rebound effect, one likely explanation is that the monitoring process has to keep the unwanted thought close to consciousness in order to watch for it, and so once the operator stops actively providing alternative thoughts, the unwanted thought becomes more likely to come to mind than if no effort to suppress had been initiated in the first place. For instance, participants who were asked to not think about a particular person in their lives right before they went to bed were more likely to dream about the person than were participants who did not receive this request (Wegner et al., 2004)!

Wegner argues that monitoring is an automatic process: It searches for signs of an unwanted thought without demanding too much mental energy. The operator, in contrast, is a controlled process, requiring more mental effort and energy to carry out. This leads to a testable prediction about the two components of thought suppression. We would expect that when a person is cognitively busy or dreaming, the automatic monitoring process will continue searching for instances of an unwanted thought, but the controlled operator process responsible for focusing attention away from that thought will be disabled. Consequently, the undesired thought kept accessible by the monitoring process will become especially likely to pop into consciousness or our dreams.

Wegner and colleagues have applied ironic process theory to many contexts in which people try to suppress a thought or a behavior. They consistently find that when people are under stress, distraction, or time urgency, efforts at thought suppression generally backfire (Wegner, 1994). Here are a couple of examples: If people reminisce about sad events and then try to suppress sad feelings, they are generally successful when cognitive load is low, but trying to suppress sadness backfires when people are asked to remember a string of nine numbers at the same time (Wegner et al., 1993). When people are listening to mellow, new age music, they can follow directions to ignore distracting thoughts and go to sleep quickly, but if their heads are filled with booming marching-

There are two basic ways to minimize ironic processing. One is to keep distraction, stress, and time urgency to a minimum when regulating our thought and behavior. We can, for example, work in a quiet room or start projects far in advance of their deadline. Of course, we can’t always avoid mental stressors. The second strategy is simply to stop trying to control your thoughts when cognitive strain is likely to be present. Under such circumstances, disengaging from effortful control can eliminate the ironic process. In fact, a form of psychotherapy called paradoxical intervention involves telling the client to stop trying to get rid of their problem. You can’t sleep when you go to bed? Stop trying to! It seems to work, at least for some people, some of the time (Shoham & Rohrbaugh, 1997).

182

Insufficient Energy, or Ego Depletion

Our lack of success with trying to suppress unwanted thoughts highlights the more general point that goal pursuit is often an effortful process, and therefore our goals compete for a limited supply of mental energy. Perhaps you are a strong environmentalist and value recycling, but one day you come home from a long day of work and studying. You barely have enough energy to make yourself dinner. You look at the mess of recyclables and nonrecyclables, say “Forget this!” and toss them all in the trash. Why would you give up so easily on a cherished value?

Muraven, Tice, and Baumeister (1998) argue that the ego is like a muscle. We have a certain amount of ego strength that allows us to regulate and control our behavior. But just as our quadriceps ache after we’ve run five miles, our ego strength becomes depleted by extended bouts of self-

Ego depletion

The idea that ego strength becomes depleted by extended bouts of self-

Ego depletion can even explain why people sometimes engage in risky behaviors. In another study (Muraven et al., 2002), participants first had to engage in the effortful task of suppressing their thoughts (or not). Afterward, they were asked to sample different types of beer before taking a driving test. Because these participants knew that their driving skills would be measured, they should have been motivated to limit how much alcohol they drank. But despite this motivation, participants who had engaged in the effortful control of their thoughts beforehand drank more beer than those who were not cognitively depleted.

The good news is that our ego strength can be exercised and replenished. Research suggests that spending just two weeks focusing on improving your posture or monitoring and detailing what you eat can strengthen your ability to self-

Recent research is even beginning to uncover the biological mechanisms that underlie self-

183

Together, these findings support the hypothesis that self-

These findings spurred Inzlicht and Schmeichel (2012) to dig deeper into the process behind ego depletion. They explored why self-

Getting Our Emotions Under Control

A specific example of self-

But if suppressing your emotions is not a good way to control your feelings, is there another strategy that will work better? Building on cognitive appraisal theory of emotion, introduced in chapter 2, James Gross (2001) proposed that an alternative to emotional suppression is cognitive reappraisal—reexamining the situation so that you don’t feel such a strong emotional reaction in the first place. In the example of being dumped, you might excuse yourself to go to the restroom and use that time to think about all of your partner’s annoying habits that actually drove you crazy, or about the fact that you are planning to move to Ghana next year with the Peace Corps and won’t have the time for a relationship anyway. With these cognitions in mind, this sudden break up can seem a little more like a blessing than a curse.

Cognitive reappraisal

The cognitive reframing of a situation to minimize one’s emotional reaction to it.

But can the mind really control the heart through reappraisal? Research suggests that it can (Gross, 2002). A typical experiment uses a method similar to that previously described in research by Muraven and colleagues (1998). Specifically, Gross (1998) showed people a disturbing film of an arm amputation. He instructed one group of participants simply to watch the film (the control condition). Another third of the participants were told to suppress their emotional response so that someone watching them wouldn’t be able to tell how they were feeling. A third group was instructed to reappraise the film, for example, by imagining that it was staged rather than real. Compared with the people in the control condition, people who suppressed their emotion did make fewer disgust expressions, but they showed increased activation of the sympathetic nervous system and still reported feeling just as disgusted. In contrast, participants who reappraised the film showed no increase in their physiological signs of arousal and reported lower levels of disgust than participants in the control condition. The effect of reappraisal on reducing negative emotions has been replicated in other research using more sensitive physiological measures of negative affect, such as activation of the amygdala (Goldin et al., 2008).

184

These findings suggest that reappraisal can be an effective way to avoid feeling strong negative emotions. Certainly the consequences are better than suppression, which can actually have the ironic effect of exacerbating your negative feelings. But we also have learned from Muraven’s research that suppressing emotions has cognitive costs. Do the benefits of reappraisal come at the price of cognitive resources? The answer seems to be no. In a study by Richards and Gross (2000), participants were asked to suppress, reappraise, or simply view a series of negative images. Later they were tested on verbal information that had been presented with each picture. Participants who suppressed their emotions did worse on this memory task than those who just viewed the images, but the people who were instructed to reappraise their emotions did not show these same memory impairments. Taken together, these findings suggest that probably the best strategy for dealing with a difficult situation is to reappraise it in a cooler, more objective way so as to avoid fully feeling negative emotions that would be costly and difficult to suppress.

APPLICATION: What Happened to Those New Year’s Resolutions? Implementing Your Good Intentions

|

APPLICATION: |

| What Happened to Those New Year’s Resolutions? Implementing Your Good Intentions |

What about times when we believe we can achieve our goals and yet we have difficulty actually getting started? Peter Gollwitzer (1999) points out that because our attention usually is absorbed in our everyday activities, we often make it through our days without ever seizing opportunities to act on our goals. Imagine you wake up on New Year’s Day, look in the mirror, and make a resolution: “I’m going to be a better friend from now on!” Sounds great, but throughout the day your attention is absorbed in your usual tasks, and as you fall asleep that night you think to yourself: “Hey! I never got a chance to be a better friend!” The problem is that the goal still is a broad vision, and you haven’t yet specified how you will implement your goal. Gollwitzer claims that we’ll be more successful if we create implementation intentions, mental rules that link particular situational cues to goal-

Implementation intentions

Mental rules that link particular situational cues to goal-

Forming implementation intentions helps people reach all sorts of goals. For instance, it can encourage people to pursue their exercise goals, as demonstrated in a study by Milne, Orbell, and Sheeran (2002). College students were reminded of their vulnerability to heart disease and the benefits of exercising to reduce their risk. They had the goal of exercising more, but they had not formed any implementation intentions. This intervention was mildly successful, increasing the percentage of students who exercised regularly from 29% to 39%. In another condition, this intervention was coupled with instructions to form implementation intentions, that is, specific rules for when and where to exercise. (“As soon as I get up, I’ll go for a 3-

185

Identifying Goals at the Wrong Level of Abstraction

Throughout this chapter, we’ve seen how humans regulate their behavior in ways that make us very different from any other species, past or present. Unlike dogs and cats, we often devote huge chunks of our lives to attaining or avoiding what are essentially abstract ideas, such as “being a good friend” or “financial failure.” If we are successful at achieving these goals, it’s because we can think in flexible ways about our own actions, sometimes viewing them as steps toward broader goals and other times breaking them down into smaller, more concrete goals. So far, so good; but as you may remember from chapter 2, people generally prefer to identify their actions at a moderately abstract level so that those actions seem meaningful. For example, a football player heading onto the field will prefer, all things being equal, an abstract interpretation of his action, such as “playing to win” or “impressing the coaches,” to more concrete interpretations, such as “stepping onto the field and shifting my balance forward.”

What levels of abstraction help us achieve our goals? Research on this issue has revealed two basic findings (Vallacher & Wegner, 1987). First, people perform easy tasks best when they identify them at relatively abstract levels. Second, people perform difficult tasks best when they identify them at low levels of abstraction. Parenting is a particularly daunting task: Trust us, or better yet, recall—

When We Can’t Let Go: Self-regulatory Perseveration and Depression

There are times, however, when a person is having a difficult time and would benefit from viewing goals in more abstract terms. Moving up the hierarchy to more abstract identifications is particularly valuable when attempts to meet a goal continue to be unsuccessful. In such cases, attention will shift upward in the hierarchy to allow the person to consider his or her goals more broadly. This is useful because it allows the person to search for alternative lower-

For instance, you may choose the goal of signing up online for a philosophy class that would help you complete your degree requirements. But what happens if the online sign-

186

But sometimes people persist in pursuing a goal long after it’s no longer beneficial to do so. The self-

Self-regulatory perseveration theory of depression

The theory that one way in which people can fall into depression is by persistent self-

Getting dumped is brutal. How do you get out of the doldrums and avoid being depressed? Self-

[Getty Images/Blend Images]

But not all goals are so easily abandoned as your favorite pencil. If a goal is a central source of self-

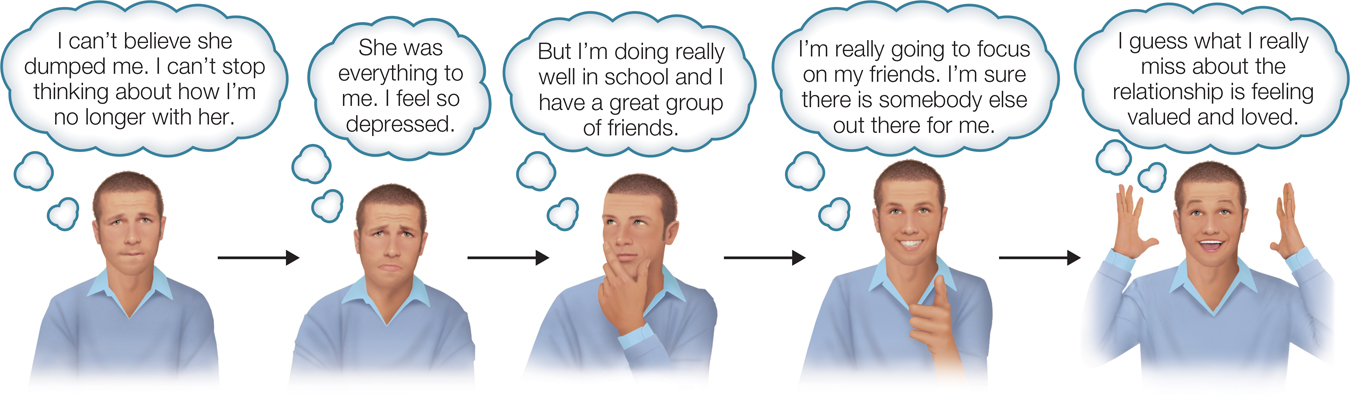

FIGURE 5.6

The Positive Spiral of Recovery

According to self-

The reason for this escalating pattern of problems is that excessive inward focus on the self magnifies negative feelings, promotes attributing one’s problems to oneself, and interferes with attention to the external world, leading to further failures. The spiral of misery and self-

The positive spiral of recovery begins by identifying the abstract goal that the now unattainable goal was serving. In this way, the person can find alternative means of satisfying that abstract goal (FIGURE 5.6). As he or she invests time and energy in those alternative means, self-

187

Maintaining a state of optimal well-

God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change;

courage to change the things I can;

and wisdom to know the difference.

SECTION review: Self-regulatory Challenges

|

Self- |

|

Research has discovered numerous factors that make self- |

|---|

|

Strengthen willpower by activating the hot system and avoiding factors that block the cool system, such as stress, cognitive overload, alcohol, or freshly baked cookies. Minimize ironic processing— Strengthen your self- Reappraise difficult situations as a way to avoid feeling strong negative emotions. Form “if– Start with abstract goals in mind, but break them down into smaller, concrete actions to make difficult tasks more easily attainable. Maintain a balance between self- |

CONNECT ONLINE:

Check out our videos and additional resources located at: www.macmillanhighered.com/