6.4 Motives for Growth and Self-expansion

All over the world, and indeed in your own community, you’ll find astounding examples of people exploring new ideas, of flexible and integrative thinking, and further, of people loving, playing, and developing wisdom and maturity. These examples attest to powerful human motives for personal growth and self-

Rank’s and Erikson’s perspectives contributed to an influential movement in the 1960s known as humanistic psychology. One prominent theorist in this tradition, Carl Rogers (1961), posited that people are naturally motivated to expand and enrich themselves, but that conformity to society’s expectations often derails this process. Abraham Maslow (e.g., Maslow et al., 1970) similarly proposed that all humans are fundamentally motivated toward self-

Self-determination Theory

Think ABOUT

Consider for a moment why you are reading this textbook. Are you doing it because you think you have to, and it’s a necessary step to completing this course? Or perhaps you would feel guilty if you didn’t? Or maybe you are doing it because you truly enjoy reading and mastering this material?

222

According to Ed Deci and Rich Ryan’s self-

Self-determination theory

The idea that people function best when they feel that their actions stem from their own desires rather than from external forces.

To illustrate, imagine that Nick and Mikalya are in medical school. Both are going to classes, studying for tests, and so on. Nick goes to medical school purely because he feels obligated to fulfill his family’s wish that he become a doctor and make lots of money. Parental expectations and financial rewards are the controlling factors, not Nick’s authentic desires. Nick’s behavior is an example of extrinsically motivated behavior. In contrast, Mikalya is going to medical school because being a doctor connects with her core sense of self and her value of helping others maintain their health. Although she may not enjoy all aspects of the process, such as that grueling pharmacology class, the goal of being a doctor is something she personally wants to achieve, regardless of what others expect of her. Mikalya’s behavior is intrinsically motivated.

Self-

Relatedness: being meaningfully connected with others

Autonomy: feeling a sense of authentic choice in what one does

Competence: feeling effective in what one does

When people are in social situations that allow for the satisfaction of these needs, they experience their action as more self-

The late singer/songwriter and philanthropist Harry Chapin illustrated the value of feeling self-

[Text from Harry Chapin Gold Medal Collection, produced by Elektra/Asylum Records, a division of Warner; photo by Keith Bernstein/Redferns/Getty Images]

Does it matter whether people feel self-

Research backs this up. Across a wide variety of domains—

In fact, when the social environment promotes our self-

223

The power of self-

Locus of control

The extent to which a person believes that either internal or external factors determine life outcomes.

Think ABOUT

Around the globe, millions of people believe that significant outcomes in their lives, including the courses of their careers and romantic relationships, are determined by the movements of celestial bodies. You may have found yourself consulting a horoscope for clues to your fate. Recalling what you have learned about self-

The Overjustification Effect: Undermining Intrinsic Motivation

What types of social contexts can thwart a person’s sense of autonomy? Think about something that you typically enjoy doing for its own sake, such as reading, mountain climbing, or dancing. Now imagine that you started to get paid for this activity: would you enjoy it more or less? Common sense and behaviorism would suggest that if you liked it already, you’d like it even more if you received extrinsic monetary rewards for doing it. But not so fast. In a seminal study to address this question (Lepper et al., 1973), preschool children were asked to do some coloring, an activity most children find enjoyable. One group of children was promised a “good player” ribbon for their coloring; another group was promised no reward. Later, when all the children were given a free choice among a variety of activities, the children who received the promised ribbon reward were less interested in coloring.

Why would this happen? Self-

Overjustification effect

The tendency for salient rewards or threats to lead people to attribute the reason, or justification, for engaging in an activity to an external factor, which thereby undermines their intrinsic motivation for and enjoyment of the activity.

Because extrinsic inducements are used so often in child-

224

Do rewards always undermine intrinsic motivation? If the reward is viewed as an indicator of the quality of one’s efforts, rather than an inducement to engage in the activity in the first place, it often actually improves performance and intrinsic interest rather than undermining it (Eisenberger & Armeli, 1997). Rewards also can be effective as long as people aren’t aware that the reward is controlling their choices. Furthermore, rewards are effective when given in an atmosphere that generally supports relatedness, autonomy, and competence. A sales manager who is friendly, caring, and appreciative, and who doesn’t micro-

APPLICATION: How to Maximize Self-growth

|

APPLICATION: |

| How to Maximize Self- |

Self-

The Search for Happiness Video on LaunchPad

The Search for Happiness Video on LaunchPad

Pursue Goals That Support Core Needs

We’ve just seen that why we pursue a goal is an important factor in our growth; what goals we pursue also matters. Some goals strengthen a meaningful relationship or exercise a talent, helping to satisfy personal core needs (Sheldon & Elliott, 1999). Other goals, such as striving to be popular, do so less well. Indeed, people who pursue materialistic goals of fame and fortune tend to have lower levels of life satisfaction, creativity, and self-

Get in the Zone

Have you ever participated in some activity where your sense of time seems to evaporate, you lose all sense of your self, and you are totally focused on the activity at hand? Maslow referred to such instances as “peak experiences,” and he felt that they contribute to self-

Flow

The feeling of being completely absorbed in an activity that is appropriately challenging to one’s skills.

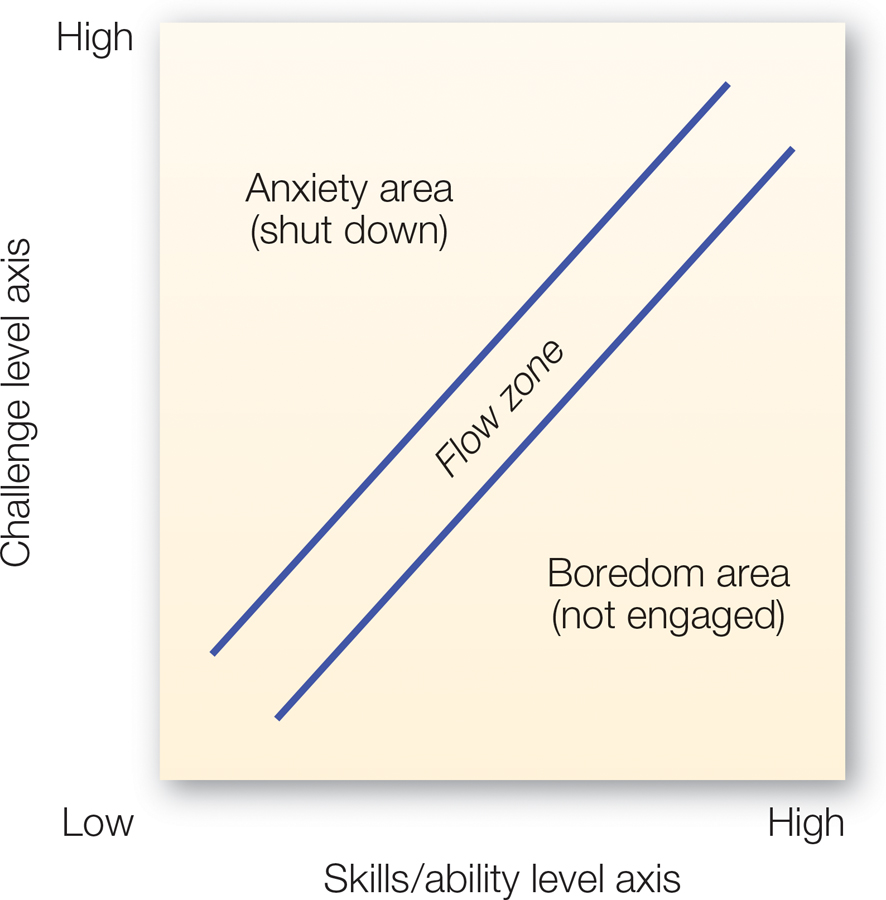

FIGURE 6.7

Csikszentmihalyi’s Concept of Flow

When the challenge level of a task, situation, or role matches well with the person’s skills and abilities, he or she experiences an enjoyable and absorbed feeling known as flow.

[Research from Csikszentmihalyi (1990)]

Flow is achieved when the challenge of a situation, person, or task is just above our typical skill level, requiring a full engagement of all our concentration and focus. As you see depicted in FIGURE 6.7, when the challenge is too high, we experience anxiety, and when the challenge is too low, we experience boredom. But when skills and challenges match, intrinsic motivation and flow can emerge. This idea helps explain why video games are so popular: They are designed so that once you master a given level, there’s another, higher level to challenge you, so you always have a good match for your skill level (Keller & Bless, 2008). Although people cannot be in flow all the time, research suggests that even recalling past peak experiences can be beneficial and actually contributes to better physical health (Burton & King, 2004).

225

Act Mindfully

The study of mindfulness, attentiveness to the present moment in which one is actively involved with one’s actions and their meaning (Brown et al., 2007; Langer & Moldoveanu, 2000), grows out of traditions of contemplative thought such as Buddhism and Stoicism. According to Ellen Langer (1989), mindfulness can be understood by contrasting it with its opposite, mindlessness. When we act mindlessly, we habitually engage with our actions and the external world, and we rarely consider novel and creative approaches to life. The self becomes stagnant. But when we’re mindful, we open ourselves up to consider the world and ourselves in new, more multidimensional ways. People trained in mindfulness show less anxiety and fewer symptoms when coping with medical issues (Kabat-

Mindfulness

The state of being and acting fully in the current moment.

Skiing is one example of flow. Good skiers get the rush on the really difficult slopes, whereas novices can experience the exhilaration on much easier slopes. In both cases, though, the challenge demands a full engagement of one’s skill.

[Left: Matthaeus Ritsch/Shutterstock; right: Photobac/Shutterstock]

Expand Your Mind: Explore the World

Sometimes simply exposing the self to unfamiliar environments can help a person to view the world more creatively and openly. Have you ever had a creative idea—

The idea that exposure to new environments can stimulate creativity is also one reason your university or college encourages you to study abroad, and why employers often seek to increase cultural diversity in the workplace. In fact, research shows that even brief exposure to a foreign culture can improve creativity. In one study (Leung & Chiu, 2010), Euro-

Foster a Positive Mood

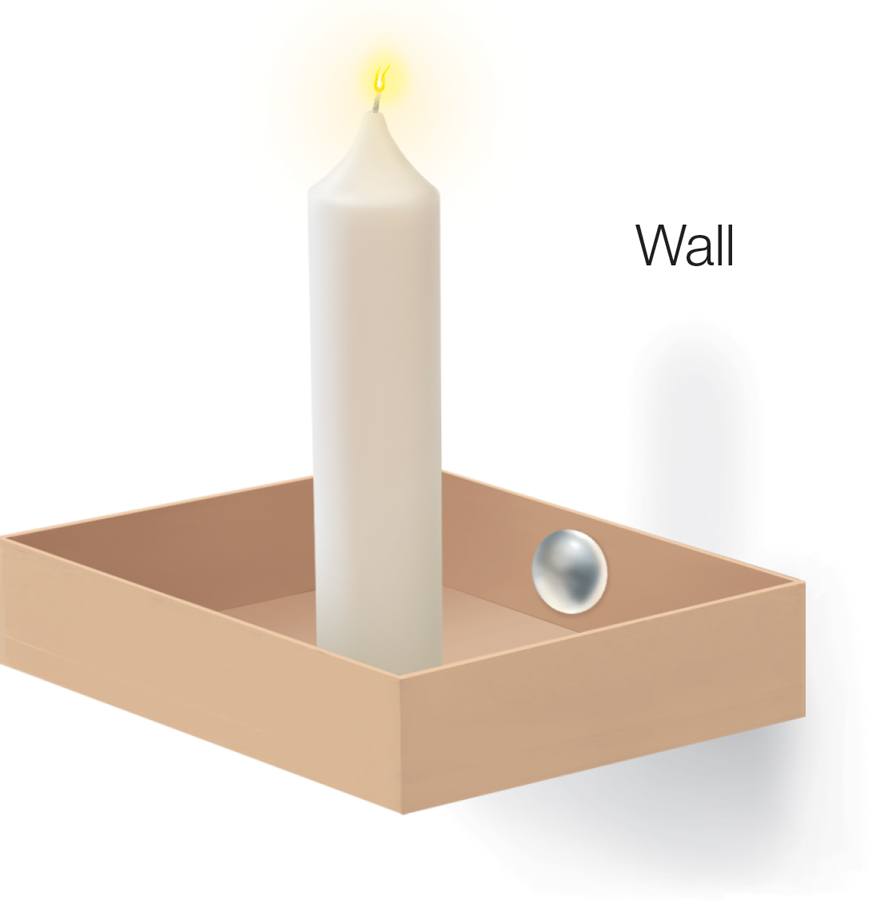

FIGURE 6.8

Matches, Tacks, Candle

One test of creative thinking is to ask a person how to use these objects to attach the candle to a corkboard so it will burn without wax dripping onto the floor. Before turning the page, see if you can figure out the solution.

Positive emotions such as happiness and excitement can stimulate creative thought, in part because they tell the person that things are safe in the world and it’s okay to explore novel experiences (Fredrickson, 2001; Lyubomirsky et al., 2005). One way that positive mood stimulates growth is by making it more likely that the person will think in new ways and find creative solutions to problems. In an illustrative study (Isen et al., 1987), some participants were put in a positive mood by watching five minutes of a funny movie, whereas participants in the control condition watched a neutral movie. Participants were then given the objects in FIGURE 6.8—a box of tacks, a candle, and a book of matches—

FIGURE 6.9

Solution to Question

Here is how it can be done. They key is being able to view the box containing the tacks in a different way than you usually would.

226

SOCIAL PSYCH at the MOVIES

Blue Jasmine

Blue Jasmine

The 2013 film Blue Jasmine, written and directed by Woody Allen, illustrates a woman’s struggle with dissonance, self-

Eventually she shifts her focus toward marrying a wealthy suitor to regain her status and transform her self-

Throughout the film, Jasmine is obsessed with trying to maintain face in light of these events. She recounts her humiliation at being seen working in a department-

Part of Jasmine’s current struggle stems from her inability to reduce the dissonance caused by these past actions and their foreseeable negative consequences. She feels guilt and shame both about her actions and about having been cheated on extensively by the philandering Hal. His unfaithfulness brought her to initiate his downfall with a call to the FBI. Despite his complicity in his own fate, Hal’s arrest and eventual death are not easy things for Jasmine to rationalize. When she meets her eventual fiancé, her intelligence, charm, and physical attractiveness appeal greatly to him. But instead of being honest about her past and her current situation, she portrays herself as a successful designer and claims that her husband was a surgeon who died of a heart attack. When these lies come to light, her engagement and her easy path back to high social status go up in smoke.

Jasmine, stripped of self-

In fairness to both the fictional Jasmine, and to real women who have made similar choices in their lives, Jasmine was in part a victim of how cultures guide people’s ways of seeking and maintaining self-

227

Challenge Versus Threat

Generally, negative experiences, such as feeling inadequate, unfulfilled, or threatened, motivate people to seek out security, driving them to cling to the safe and familiar parts of life and to cut off growth. Many studies show that people faced with threatening thoughts, such as their mortality or others’ disapproval of them, respond with less interest in exploring new experiences (Green & Campbell, 2000; Mikulincer, 1997) and are narrower and more rigid in their thinking (e.g., Derryberry & Tucker, 1994; Fredrickson & Branigan, 2005; Landau et al., 2004; Zillman & Cantor, 1976).

Yet a popular cliché is philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche’s famous line: “What doesn’t kill me, makes me stronger.” Indeed, Nietzsche was a strong proponent of the idea that to achieve a more freely determined and satisfying life, the person must face distressing truths and endure hardships. But given how stress and anxiety often stifles growth, how can this be? It depends on how people interpret stressful situations. According to James Blascovich and colleagues (Blascovich & Tomaka, 1996; Blascovich & Mendes, 2000), when people face stressful situations such as taking a test or giving a speech, they assess whether they have the resources to meet the demands of the situation. When they conclude that their resources are inadequate, they feel threatened, but when they view their resources as meeting or surpassing the demands, they feel challenged. This feeling of challenge provides an opportunity for growth.

228

In fact, whether people respond to a stressor with feelings of threat or challenge is reflected in their bodies’ physiological response. When people feel threatened, their heart rate increases but their veins and arteries don’t expand to allow blood to flow easily through the body. People’s heart rate similarly increases when they feel challenged, but here the veins and arteries dilate to improve blood flow. And feeling challenged as opposed to threatened can make a difference in performance. Blascovich and colleagues (2004) had college baseball and softball players imagine a stressful game situation at the beginning of the season while their physiological responses were being monitored. Those whose bodies signaled a challenge response actually performed better over the course of the season than those who showed a threat reaction.

Even Traumatic Experiences Can Promote Growth

When are thoughts of mortality likely to lead to defensiveness? When might they stimulate growth? Thinkers such as Seneca and Martin Heidegger argued that when people think about death in a superficial way, they are more likely to avoid their fear by clinging to conventional sources of meaning and self-

Elderly folks are particularly likely to think about death a great deal, in part because they have generally known more people who have died and are closer to their own end. Research shows that being close to the end has some positive consequences for the elderly (Carstensen et al., 1999). It leads them to want to maximize their enjoyment of life. Elderly people are especially interested in being with those they really care about, and they focus on the positive, how the glass of life is half full rather than half empty. Indeed, they are wise in another important way: they are consistently happier than younger people (Carstensen, 2009; Yang, 2008).

Why are older people better able to appreciate life and connect to their authentic goals? Perhaps as one approaches the loss of everything, it becomes easier to appreciate those things before one loses them. The poet W. S. Merwin (1970, p. 136) put it this way:

and what is wisdom if it is not

now

in the loss that has not left this place

229

SECTION review: Motives for Growth and Self-expansion

|

Motives for Growth and Self- |

|

People are motivated for personal growth and self- |

|

|---|---|

|

Self-

|

Overjustification effect Initially intrinsically motivated behaviors can, if rewarded with external incentives, come to feel extrinsically motivated, with consequent decreases in interest and enjoyment. |

|

Application: Maximize self-

|

|

CONNECT ONLINE:

Check out our videos and additional resources located at: www.macmillanhighered.com/