7.5 Compliance: The Art and Science of Getting What You Want

Conformity often involves implicit pressure. But individuals also wield influence in one-

The study of compliance has revealed a handy toolkit of methods to bring someone else’s behavior in line with a request. As you learn about these methods, you’ll notice how they are used all the time by advertisers, salespeople, and others who are in the business of influencing your consumer behavior. In fact, many of these methods were discovered when the social psychologist Bob Cialdini spent a few years undercover, going into car dealerships and taking other sales positions to find out which sales techniques are the most effective for getting people to pull out their credit cards (Cialdini, 2006). Of course, methods of compliance are also useful outside the marketplace for changing a range of behaviors, from getting your roommate to do the dishes to getting people to give generously to charities. Next, we review the most well-

SOCIAL PSYCH at the MOVIES

12 Angry Men

12 Angry Men

The classic 1957 film 12 Angry Men (Fonda et al., 1957), starring Henry Fonda and directed by Sidney Lumet, portrays in great detail one riveting example of minority influence while also illustrating other factors in social influence. The film opens with 12 jurors who have just heard the murder trial of a boy accused of killing his father. The jurors settle into the deliberation room, muttering that it appears to be an open-

What follows is a compelling portrayal, filmed exclusively in the confines of this one room, of the process by which one man succeeds in changing the minds of 11 other jurors. Demonstrating how art can anticipate scientific insight, the film highlights a number of factors that subsequent research has shown increase the likelihood of minority influence. Fonda’s character (whose name we don’t learn until the final scene of the film) takes some time to ponder his initial vote but thereafter consistently advocates an open-

Henry Fonda’s character also has brief personal conversations with some of the other jurors, which helps to break down the walls between them. He no longer seems like an outcast. And as research shows, the more people identify with a minority, the more influential that minority can be.

Three of the more noteworthy performances (in the context of across-

After the film was released, each of these tactics was subsequently examined and supported in empirical research on how and when minorities can influence numerical majorities.

251

Self-perception and Commitment

According to Bem’s self-

Foot-in-the-door effect

Phenomenon whereby people are more likely to comply with a moderate request after having initially complied with a smaller request.

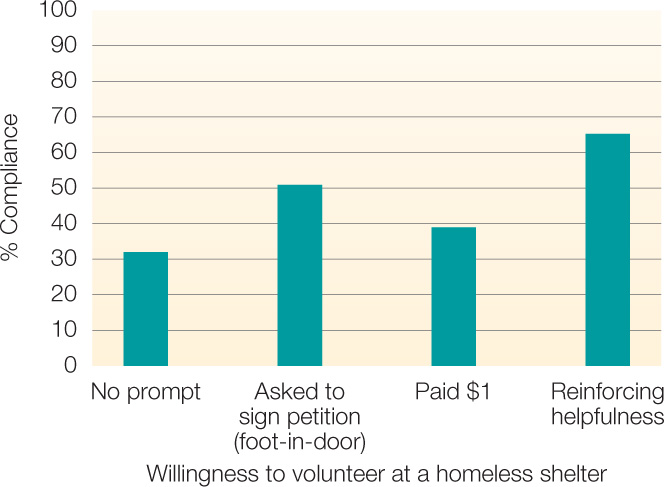

Imagine that you are participating in the following study by Burger and Caldwell (2003). In one condition, you spend time completing several questionnaires. At the end of the study, you are asked if you would be willing to volunteer a couple of hours the following weekend helping to sort food donations for a local homeless shelter. If you are like most participants, you probably would come up with some excuse for why you wouldn’t have the time. In this condition, only 32% of the participants volunteered. But now rerun the simulation with the following change: At the very beginning of the session, another participant asks if you might be willing to sign a petition to increase awareness about the plight of the homeless. This is an easy enough thing to agree to, and you add your name to the list. But having done so, you now feel like a champion of the underprivileged. What happens when you are next asked to spend your Saturday afternoon sifting through food donations? In the real experiment, 51% of the participants complied with the fairly substantial larger request if they had first complied with a smaller request (FIGURE 7.7). This significant increase in compliance resulted from simply carrying out an initial, smaller request.

252

FIGURE 7.6

The effect of self-

Burger and Caldwell’s (2003) study shows how self-

[Data from Burger & Caldwell (2003).]

The foot-

This raises an interesting possibility: If a person initially complies with a small request for extrinsic reasons, such as a monetary reward, will she be less likely to infer that she is the helping type? Perhaps yes, if she attributes her compliance to the extrinsic factor. In this case, when she is later asked to comply with a larger request, she will feel less pressure to act in ways that are consistent with her self-

Our motivation to view ourselves as consistent also contributes to a social norm to honor our commitments. Once you make a public agreement, it is considered bad form to back out on your half of that agreement. This norm for social commitment underlies the strong sense of trust that is one of the building blocks of cooperative relationships. Most of the time, behaving in line with such a norm will foster healthy social bonds. Those who renege on their agreements earn a reputation for being undependable, flaky, and untrustworthy. But the norm for social commitment can get you to do things you might not otherwise want to do.

Norm for social commitment

Belief whereby once we make a public agreement, we tend to stick to it even if circumstances change.

For example, this norm can make you feel trapped in a decision and forced to accept a lowball offer. Lowballing can take different forms, but the general principle is that after agreeing to an offer, people find it hard to break that commitment even if they later learn of some extra cost to the deal. Consider this technique in the context of trying to sell someone a new car. The strategy is to offer the customer what seems like a great deal and get him to commit to the idea of buying that particular new car. Then only after the customer has already mentally committed to buy the car is a certain “error in calculation” or “salesperson-

Lowballing

Occurs when after agreeing to an offer, people find it hard to break that commitment even if they later learn of some extra cost to the deal.

Researchers have studied lowballing in a number of real-

253

Lowballing is different from the foot-

Reciprocity

Vampire bats also seem to follow the norm of reciprocity—

[Michael Lynch/Shutterstock]

The age-

Because the norm of reciprocity is strong, it is often used to induce compliance. If you have ever donated money to an organization after it provided you with a free gift (preprinted address labels, for example), then you have felt the pull of reciprocity. But why do we reciprocate? Is it a built-

A clever experiment by Regan (1971) gives us some clues to answering these questions. Each participant worked on a task alongside a confederate who came across as either very likeable or downright rude. In one condition, the confederate returned from a break halfway into the study and, as an unexpected favor, gave the participant a can of Coke. In a second condition, the participant also received a Coke, but this time from the experimenter. And in a third condition, the participant did not receive this unexpected gift. At the end of the session, the confederate asked the participant if he would be willing to help him out by purchasing lottery tickets for a fundraiser.

Regan figured that if people help others simply because they like them, then participants in this study would not help the rude confederate, even if he kindly delivered a Coke. Also, if receiving favors increases helping simply because it improves mood, then participants would be more willing to help the confederate if they had been given a free Coke, regardless of whether it came from the confederate or the experimenter. The results did not support either of these hypotheses. Instead, people bought about 75% more tickets when the confederate had given them a Coke compared with the other two conditions, regardless of whether the confederate was generally likeable or rude. This finding suggests that liking or being in a good mood are not essential ingredients of reciprocity. That is, although both positive moods and liking do tend to increase compliance, as you might expect, they were not especially influential in this context (Carlson et al., 1988; Isen et al., 1976). Rather, this experiment shows the power of reciprocity. So even if you despise your neighbor, you might still find yourself agreeing to take care of her pets if she’s been bringing in your trash cans from the street.

254

However, reciprocation does have its limits. Simply doing someone a favor generally will not lead the person to comply with your request if you’re requesting something that would violate the person’s moral standards or put the person at risk, such as helping you to cheat on a test (Boster et al., 2001). So although you might take care of Rover from next door to reciprocate your neighbor’s past favors, you may draw the line if he asks you to, say, help him fudge his income tax return.

Norms toward reciprocity can also play a role in negotiations. Conventional wisdom might tell you that when you approach your boss about requesting a raise, you might not want to start with a high initial request that could alienate your superior and stop the process before it starts. But such conventionality might not be so wise, because it ignores the powerful role that reciprocity can play. Although your boss might deny your request for a hefty $10,000 raise, the guilt she might experience from turning down your request could lead her to compromise at a $5,000 raise, which might have been the amount you were hoping for all along. This is called the door-

Door-in-the-face effect

Phenomenon whereby people are more likely to comply with a moderate request after they have first been presented with and refused to agree to a much larger request.

Consider a classic study that Cialdini carried out with his research team (Cialdini et al., 1975). Members of his team approached students around campus and asked if they would be interested in volunteering their time on an upcoming Saturday chaperoning a group of juvenile delinquents on a trip to the zoo. With no financial incentive and concerns about lacking the experience, 83% of those approached refused. But the experimenters first approached another group of students with the offer of a different kind of volunteer opportunity with the same organization: spending two hours a week for two full years as counselors to delinquent kids. Not surprisingly, no one approached was willing to make this extreme commitment of time. However, when their refusal was followed by a smaller request to chaperone for one Saturday afternoon (the same request initially given to the other group of students), half of the students agreed to help out. In other words, the door-

How is reciprocity involved here? When the person being approached with a request views the smaller compromise offer as a concession, that person can become motivated to reciprocate and do her part to maintain good faith in the exchange. This then can lead her to be more likely to accept the compromise offer. To put it simply, it is as if the person making the requests is doing you a favor by offering you the smaller request.

255

Social Proof

During college, one of the authors of this textbook spent a summer selling educational books door to door. The job entailed trying to meet and talk to every family in a neighborhood. Whenever a family placed an order for books, its name was added to a list of buyers. The list was shown to potential customers as a sort of proof that the product was good. In one community, your author was fortunate enough to have several high school teachers and parents in the local school district purchase the books so that their names adorned the buyer sheet. When she approached the house of the high school’s principal, he took just one look at this list and instantly said, “Well then, I guess I have to buy them,” and pulled out his wallet without even taking a very close look at what it was he was buying!

This anecdote typifies the powerful effect that social proof has on our behavior. This technique capitalizes on our tendency to conform to what we believe others think and do. It is akin to making salient a descriptive norm but emphasizes the special value of information about what similar and respected others have done. As social comparison theory posits, we often look to similar others to provide us with information about what is good, valuable, and desirable. This makes our friends the most effective salespeople we know, and we commonly follow their recommendations for restaurants, movies, and clothing brands.

Social proof

A tendency to conform to what we believe respected others think and do.

If consistency means choosing a behavior that conforms to your perception of yourself, and social proof means choosing a behavior that conforms to what others are doing, you can imagine that in some cases these two compliance strategies could pull a person in opposing directions. In fact, there can be cultural variation in which strategy is more effective. For example, in one study, students from a collectivist culture (Poland) chose to comply with a request on the basis of information about how many of their peers had complied, whereas U.S. students, who are typically more individualistic, were more influenced by considering when they had complied with similar requests in the past (Cialdini et al., 1999).

Scarcity

In the summer of 2008, record numbers of people lined up for hours, sometimes days, to buy the latest must-

Might the initial scarcity of the original iPhone have contributed to its popularity?

[ChinaFotoPress via Getty Images]

Some researchers have suggested that our craving for scarce things stems from the psychological process called reactance (Brehm, 1966), which we will discuss in greater detail in our next chapter. When something is hard to get because it’s scarce, we feel that scarcity as an insult to our basic freedom of choice, and that makes us want the object even more. But because things that are in short supply often fetch a higher price, Cialdini (1987) views scarcity as a heuristic that we have learned implicitly because we simply want what is hard to attain without giving it too much thought.

256

Yet another approach proposes that things or ideas that are scarce or rare attract our attention and greater scrutiny (Brock & Brannon, 1992). As a result, our evaluations can be polarized by other information, such as strong or weak arguments for wanting the product. If at your local taquería, you are asked if you want a cinnamon twist that’s available for only a limited time, you might comply with this attempt to sell the twists only if you are also given a good reason to do so, rather than being reminded of the fact that these tasty treats aren’t even traditional to Mexican cuisine (Brock & Mazzocco, 2004).

Each of these explanations has some support, and research has not definitively favored one over the other. Regardless of the precise reason for the valuing of what’s scarce, stores and manufacturers realize and exploit this little quirk of human nature. You probably have seen countless advertisements declaring that a good deal won’t last: Limited time offer! Sale ends Saturday! Limited quantity! In fact, sometimes these offers aren’t even genuine. Take the example of a Circuit City store that was going out of business and having a “liquidation sale” for a “limited time.” Instead of lowering the prices on products, the company charged with orchestrating the liquidation of the store’s inventory actually raised prices (Glass, 2009)! Many unsuspecting customers who hadn’t done their homework flocked to the store and bought up electronics for more than they might have paid online or at a different vendor.

Mindlessness

A final way that we can sometimes get people to comply with requests that they might not otherwise do is to take advantage of the fact that we often go about our daily lives operating on autopilot. Think back to our discussion of schemas and how they affect behavior (see chapter 5), and you’ll recall that situations bring to mind certain standard scripts of what to do and say. Once these scripts are set in motion, we sometimes fail to stop and think whether what we are actually doing seems reasonable. Imagine you are standing in line at the automated teller machine when someone approaches and wants to cut in line. Presumably, you would be more likely to comply with this request if she gives a good reason, right? Maybe not.

257

Ellen Langer and her colleagues did a simple study in which a confederate asked if she could cut in line at a photocopy machine (Langer et al., 1978). When the confederate explained her request by saying that she was in a rush, 94% of people agreed to let her go ahead of them, compared with only 60% when the person gave no reason whatever and simply asked to use the copy machine. But the interesting condition was one where the confederate asked to use the copy machine “because I have to make some copies.” On the surface this sounds like a reason and probably activated a schematic impression that the requestor had a good reason, but it was really just a statement of what she planned to do. (Why else would someone use a copy machine?) Yet in a fairly mindless way, a full 93% capitulated with this request. In chapter 6, we introduced the idea that such mindlessness can stunt our creativity and lead us to behave and think in a rather rigid way. As we see here, it can also leave us vulnerable to complying with rather meaningless requests.

How often do you give money to panhandlers on the street? Would it make a difference if instead of asking for $1.00, a panhandler asked for $1.17?

[Spencer Platt/Getty Images]

Of course, some situations evoke a knee-

Why did this last group comply? Because such a specific request breaks some people out of an automatic tendency to say no while also leading them to think there must be a good reason that the panhandler needs this exact amount. In fact, follow-

258

In a related set of studies, the use of unusual phrasing for amounts of money (300 pennies as opposed to 3 dollars) was most effective at increasing sales when it was followed by an assertion of what a bargain that was (Davis & Knowles, 1999). The odd amount breaks down people’s resistance and opens them up to the suggestion that they’ve been offered a good deal. The next time you are hoping to borrow money from your roommate, you might want to remember these little tricks—

SECTION review: Compliance: The Art and Science of Getting What You Want

|

Compliance: The Art and Science of Getting What You Want |

| The study of compliance has revealed a toolkit of methods to get people to do what you want them to do. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

The foot- |

Reciprocity and social proof |

Scarcity |

Mindlessness |