7.6 Obedience to Authority

The next set of classic studies concerns obedience—doing what someone else tells you to do. This research focuses on how obedience is sometimes behavior with much more serious consequences than being taken in by a slick roommate or an infomercial. Unlike the pressure of conformity, which can often be rather subtle, the pressure to obey is very direct and explicit. And unlike compliance techniques, which involve requests, obedience involves commands. Yet like conformity and compliance, it is a very common form of social influence. It is so common because we live in societies that have a hierarchical structuring of power (Milgram, 1974). Some people, by the nature of their roles within the culture, are given the legitimate authority to tell other people what to do in particular contexts. In families, parents have authority over children; in the classroom, teachers have authority over students; in airplanes, pilots have authority over passengers; in the army, sergeants have authority over privates; and so forth. We often even obey people who are not necessarily of higher social status, such as ushers in theaters. And generally in our society such obedience is encouraged. It is deemed good when children obey their parents, students obey their teachers, employees obey their bosses, patients obey their doctors, and citizens obey the police. But in all too many historical instances, obeying authority has led people to do great harm to themselves or others. The most dramatic example was the Nazi Holocaust, the catastrophe that inspired the seminal research on obedience.

Obedience

Any action engaged in to fulfill the direct order or command of another person.

Like many social scientists back in the early 1960s, Stanley Milgram wondered about the obedience displayed by the German people during the Nazi era. How did the demented Nazi ideology and the brutality and genocide it spawned come to be embraced by an entire nation? It is not hard to imagine that Adolf Hitler was a very disturbed, hateful, narcissistic man because of some combination of genetic predispositions, childhood upbringing, and stressful life experiences. We might conclude the same of his closest Nazi allies. But how could the majority of an entire large nation participate in such egregious atrocities? Could millions of people be that deranged or evil?

259

Milgram did not think that Germany was filled with evildoers, but he did think that perhaps the German people were particularly prone to obedience because they were raised in an unquestioning environment that encouraged obedience to authorities. He speculated that living in this authoritarian society might have led citizens down the tragic path of war, genocide, and national disgrace. To understand this mass obedience, Milgram developed a laboratory situation to test people’s willingness to harm another just because an authority figure told them to do so. Because of the astounding, surprising nature of the findings, these studies have become the best-

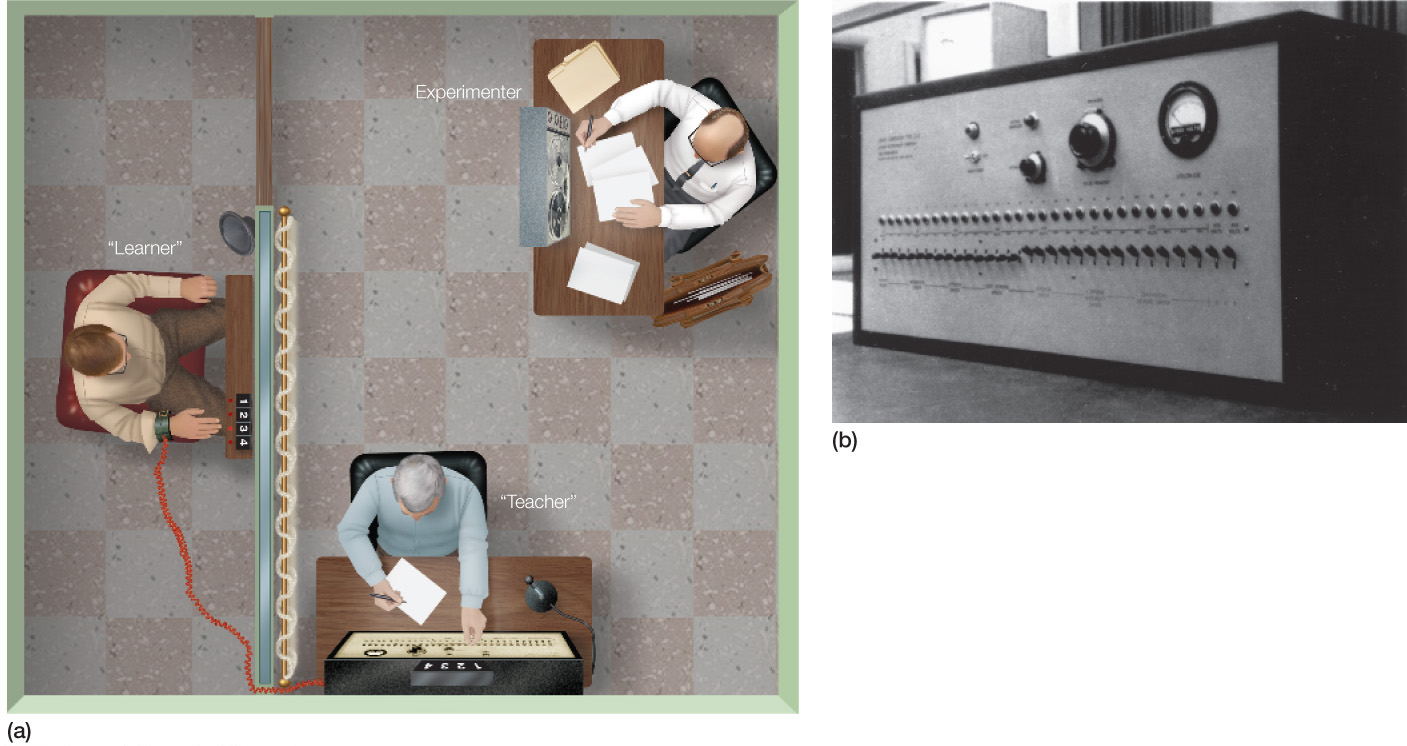

FIGURE 7.7

Milgram’s obedience studies

The drawing on the left depicts the setup in one variant of Milgram’s studies. Here the learner is in a private room while the teacher sits in a room with the shock generator (right) and the experimenter.

[(b) Stanley and Alexandra Milgram]

In his first study, conducted at Yale University, Milgram (1963) recruited 40 ordinary men, ranging in age from 20 to 50, from the New Haven, Connecticut area to participate in a study of learning. When each man arrived at the lab, he received $4.50 and was told it was for coming to the experiment and was his no matter what happened from that point on. He and another apparent participant were greeted by an experimenter who explained that the study concerned the effects of punishment on learning. However, the apparent participant was actually a confederate working with the experimenter. The participant and the confederate chose slips of paper, ostensibly to determine randomly who would be assigned to be the teacher and who would be assigned to be the learner. This drawing was actually rigged so that the participant would always be the teacher.

The learner was then strapped into a chair and an electrode was attached to his wrist. The experimenter explained that the electrode was attached to a shock generator in the next room. The teacher’s task was to read pairs of words to the learner and then test whether the learner could remember which words were paired together by choosing the correct paired word from four possible words. The learner would choose his answer by pressing one of four switches in front of him; his responses would be indicated by a light in an answer box in the adjacent room (see FIGURE 7.7a). The participant was then escorted into that room, which housed the shock generator and the answer box. The generator had 30 switches, labeled from 15 to 450 volts from left to right, in 15 volt increments (see FIGURE 7.7b). The switches for voltage levels above 180 were labeled “Very Strong Shock”; those above 240 were labeled “Intense Shock”; those above 300 were labeled “Extreme Intensity Shock”; and those above 360 were labeled “Danger: Severe Shock.”

The participant was instructed to read the word pairs and then test the learner for each word pair. Whenever the learner made an error, the participant was to give a shock to the learner. With each error, he was to increase the voltage of the shock by 15 volts. Thus, the participant would administer a 15-

260

As the study proceeded, the learner used a predetermined set of three wrong answers to every correct one. In this initial study, the learner was silent when the shocks were administered, but if the participant continued to the point of delivering 300 volts, the learner pounded on the wall. In subsequent variations of the study, starting with Study 2 of the series, the learner grunted, complained, and screamed as the shocks escalated, but these reactions did not affect the level of obedience exhibited by the participants. After the 300-

Think ABOUT

How do you think you would respond if you were the teacher in this study? What about other people? What percentage of participants do you think would go along with administering what they believed to be even the most dangerous shocks? Take a moment to think about it.

Milgram asked Yale senior psychology majors, graduate students, faculty, and psychiatrists to predict whether they would continue obeying all the way to 450 volts (about four times the voltage of a standard electrical outlet). He also asked people from these same groups to predict the percentage of participants in the study who would. No one predicted that they would do so themselves, and each of these groups predicted that fewer than 2% of participants would obey fully by continuing to administer shocks until the maximum voltage was reached.

261

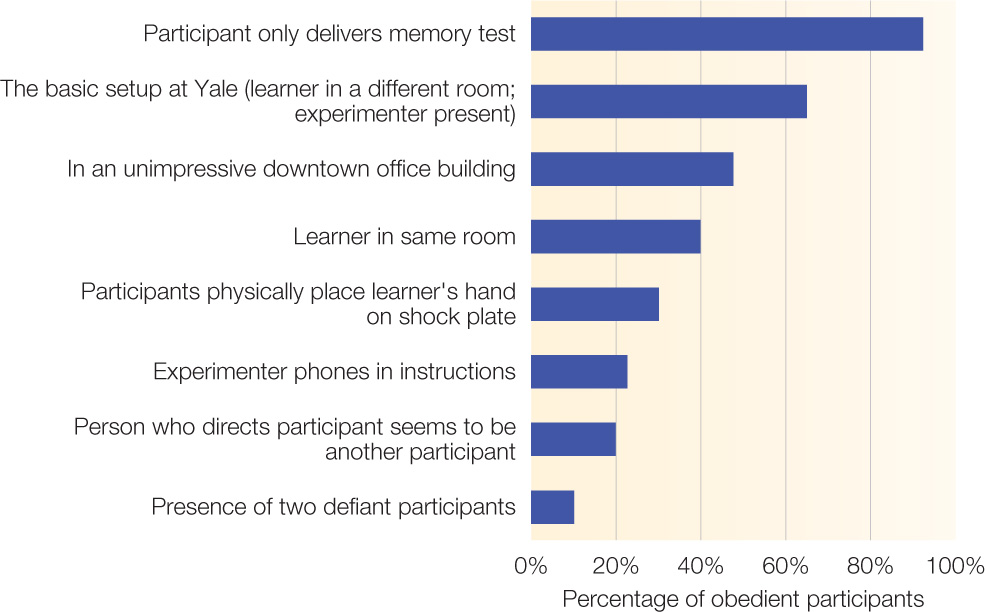

FIGURE 7.8

Factors affecting obedience

Distance and legitimacy are two important factors that influence obedience. When the “teacher” is more removed from the “learner,” the rate of obedience is higher. When the experimenter is more removed from the teacher, the rate of obedience is lower. When the authority is seen as more legitimate, the rate of obedience is higher.

[Data from Milgram (1974).]

They were quite wrong in their predictions. In fact, 26 of the 40 participants, 65%, obeyed fully to the point of agreeing to deliver a dangerous 450-

In subsequent studies, Milgram used the same shock-

These findings help explain why so many Germans contributed to the heinous actions during the Nazi era once Hitler became a legitimate authority figure in 1933. However, Milgram (1974) emphasized two points to make it clear that this proclivity to obey authority is a potential danger in any culture and in any era. First, he pointed out that horrific acts are not limited to dictatorships and fascist states. Once in power, duly elected officials in democracies are legitimate authorities who often demand actions that conflict with conscience. Second, he noted that the Nazi era was far from the first or the last time that obedience has led people to engage in egregious, destructive actions:

Jerry Burger's Replication of the Milgram Study Video on LaunchPad

Jerry Burger's Replication of the Milgram Study Video on LaunchPad

[T]he destruction of the American Indian population, the internment of Japanese Americans, the use of napalm against civilians in Vietnam, all are harsh policies that originated in the authority of a democratic nation, and were responded to with the expected obedience. . . . [W]hen lecturing . . . I faced young men who were aghast at the behavior of experimental subjects and proclaimed they would never behave in such a way, but who, in a matter of months were brought into the military and performed without compunction actions that made shocking the victim seem pallid. In this respect, they are no better and no worse than human beings of any other era who lend themselves to the purposes of authority and become instruments in its destructive processes. (1974, pp. 179–

262

Other Variables That Play a Role in Obedience

Milgram also examined the role of the physical closeness of the authority figure. If the experimenter phoned in the instructions from a distant location, full obedience was reduced to 22.5%. So the more physically distant the authority figure, the lower the percentage of obedience. This suggests that a salient authority figure will minimize disobedience, something to keep in mind when obedience is a good thing.

In addition, Milgram explored the closeness of the victim. Recall that in the original study, the victim was in a different room and could be heard but not seen. In a variation in which the victim was in the same room, full obedience dropped to 40%. And in another version of the study where participants physically had to place the learner’s hand on a shock plate, obedience dropped to 30%. This is a substantial decrease in obedience, but it is also quite remarkable and disturbing that 3 in 10 participants would obey the repeated commands even when doing so meant physically compelling the shock. The plausibility of this particular variation could be called into question, however, because the confederate had to act out receiving the shocks, crying out, screaming, and so forth. Milgram (1974) did not provide enough details for us to assess this potential problem fully.

These and other variation studies indicate that the more psychologically remote the victim, the greater the obedience to doing the victim harm. It is interesting that in modern warfare, most of the killing is done very remotely. In aerial bombing, the soldiers dropping the bombs neither see nor hear their victims. The first aerial bombings occurred during the Spanish Civil War of the 1930s. Ever since then, the highest civilian casualties in war have come from this form of violence, whose victims are physically and psychologically remote.

Milgram also wondered what would happen to the level of obedience if the real participant saw two other supposed participants defy the experimenter. As Asch found with conformity, this seemed to reduce greatly the impact of social influence, because the full obedience level dropped to 10%. Those who disobey make it easier for others to disobey, something the Nazis seemed to understand. A vivid portrayal of their common response to any act of disobedience by those on the way to or in a concentration camp can be seen in the classic film Schindler’s List: a bullet to the neck.

Thus, psychological distance from the authority, psychological closeness to the victim, and witnessing defiance all reduced obedience. But one important variation led to even more obedience than the original study. In this version, the real participant didn’t physically flip the switch on the shock generator. Rather, the real participant delivered the memory test, while another supposed participant dutifully delivered shocks up to 450 volts. In this version, 92.5% of the participants obeyed fully. This is an especially chilling finding. Very few Germans actually pushed Jews and other “undesirables” into the gas chambers or shot them, but many, many people participated in indirect ways, conducting the trains, spreading hatred of Jews and other groups, arresting them, processing paperwork, building the camps, designing mobile gas chambers at the Volkswagen automobile plants, and so on.

263

We can see from the Milgram research that at least a minority of people will eventually disobey when they feel that their own actions are physically causing harm. But when people contribute to but are not physically causing the harm, virtually all resistance to participating in atrocities sanctioned by authorities seems to vanish. Consistent with this reluctance to be directly responsible for causing sanctioned harm, it is common practice during executions for more than one individual to pull the lever, inject the serum, flip the switch, or take aim and fire. Thus no single individual knows for sure if he or she was actually physically responsible for executing the person condemned to death. The willingness to obey when one is not certain that one is physically causing the actual harm seems virtually limitless.

The lesson here is reminiscent of the oft-

In addition, if the harm is not severe physical pain and won’t occur until after the participant leaves the situation, resistance to obedience again is virtually absent. In a series of studies in the Netherlands, when participants were commanded to give negative evaluations of a job applicant’s test performance that would result in the applicant’s not being hired at a later date, over 90% of the participants obeyed these instructions (Meeus & Raaijmakers, 1995).

Anticipating Your Questions

No doubt you have found this set of studies both fascinating and disturbing. But the studies also may have raised some questions. Let’s begin with some simple ones.

Males were used exclusively in the initial set of studies, and they are more likely to engage in extreme acts of violence. Would females show a similar level of obedience? The answer is yes. Milgram’s eighth study used only females and found a similar rate of obedience.

What would levels of obedience be in other countries? Although the rate of obedience was actually a bit higher in Germany (85%; Mantell, 1971), levels of obedience similar to those in the United States were observed in a variety of other countries, ranging from relatively individualistic to relatively collectivistic ones (Blass, 2000; Milgram, 1974; Shanab & Yahya, 1978). This suggests that the explanation for obedience does not lie primarily in how authoritarian a culture is but in something about being human.

What is known about who fully obeys and who doesn’t? Not much. Researchers have examined a variety of potential personality and demographic differences between the obedient and defiant participants, and most have not distinguished the two groups (Blass, 2000). But some studies have provided relevant insights regarding factors that play a small role. Burger (2009) found that people who are high in empathy for others tended to need a prod sooner than less empathetic people, but they were ultimately just as likely to be fully obedient. There is also some evidence that the defiant participants are lower in authoritarianism. Authoritarianism is a broad personality trait that is characterized by a “submissive, uncritical attitude toward idealized moral authorities of the ingroup” (Adorno et al., 1950, p. 228). So a submissive attitude toward authority is associated with greater obedience. Milgram (1974) also reported that more educated people and those higher in moral development were less likely to obey fully.

264

What about now? The original studies were done during the early 1960s, a time when people perhaps had more faith in science and authority and the civil unrest that characterized the later part of the decade had yet to arise. Would obedience levels be lower now? Well, it turns out that it’s hard to answer this question definitively, because institutional review boards now generally do not allow people to use the Milgram paradigm. When Milgram published his initial research, there was quite an uproar over the ethicality of commanding study participants to engage in behaviors that they believed would seriously harm another person (e.g., Baumrind, 1964). Some critics focused on the stress that was imposed on participants; during the task, many displayed signs of stress, such as twitches and nervous laughter. Other critics contended that the most egregious ethical problem was that the study led most participants to discover something about themselves that could harm their self-

Obedience Video on LaunchPad

Obedience Video on LaunchPad

Milgram responded to these concerns first by noting his elaborate and thorough debriefing procedures. At the conclusion of each session, participants met the learner and saw that he was unharmed. They were fully informed of the study’s purpose in examining the powerful effects of the situation on behavior. Milgram also conducted a follow-

Think ABOUT

What position would you take?

Nonetheless, the American Psychological Association (APA) has judged that the potential harm of this threatening knowledge about the self could not be undone sufficiently, even by the best of debriefings. Thus, the full study cannot be replicated in the United States or other countries that adhere to the APA’s judgment. However, Milgram’s procedures were replicated in the Netherlands in the early 1990s and showed similarly high levels of obedience (Meeus & Raaijmakers, 1995). Moreover, in 2006, Jerry Burger (2009) obtained permission to replicate Milgram’s Study 2, which originally yielded 62.5% full obedience, as long as he had the experimenter stop the study before the participant could flip the switch for 165 volts. In this way, even if the actions of the participants had resulted in actual shocks being delivered, they would not have harmed the learners greatly. Burger also carefully screened potential participants to ensure they were not especially vulnerable to psychological harm and had a trained psychologist on site to provide counseling if needed.

Replicating the Milgram Studies Video on LaunchPad

Replicating the Milgram Studies Video on LaunchPad

In Burger’s voice-

Why is this willingness to obey a part of human nature? That’s a bigger question and we’ll address it in the next section.

265

Why Do We Obey?

Obedience to Authority Video on LaunchPad

Obedience to Authority Video on LaunchPad

Milgram offered some potential answers to the question of why we obey, each of which may have some validity. First, he proposed that we humans may have an innate propensity to obey leaders. He suggested that in situations in which individuals feel that they are in the presence of a legitimate higher authority, they acquire a state of mind in which they view themselves as agents executing the wishes of that authority figure, thereby abdicating personal responsibility for their actions. Our ancestors lived in small groups, and so Milgram posited that groups with a single leader and people willing to do what they are told may have operated more effectively in obtaining food and other resources and defending the group from threats. Thus, a capacity to obey may have been selected for as part of our heritage as group-

Nursing is one context in which socialization to obedience can occur. In fact, one study found that 21 of 22 nurses who received a phone call from a supposed doctor they did not know would have, without hesitation, administered an excessive level of medication (Hofling et al., 1966). Once obedience becomes routine, it can occur virtually automatically.

[Getty Images/iStockphoto]

Milgram also noted that a considerable portion of the socialization process involves teaching children to obey first their parents, then teachers, other adults, doctors, police, and a host of other legitimate authority figures within the culture. So we all have been taught to obey legitimate authority figures. And by and large we are rewarded when we do obey and punished, often severely, when we don’t. Obedience is the norm in all cultures and becomes a remarkable and negative phenomenon only when authority figures tell us to do things that end up causing great harm.

Besides the innate predispositions and learning experiences we humans share, Milgram also pointed to some specific factors in the paradigm he created that may have contributed to the levels of obedience in his studies. One is the gradual increase in the severity of the actions in which the participants were commanded to engage. Fifteen volts is barely a noticeable tickle, a 30-

Can you think of any theories we have covered which could explain how actions once taken can increase commitment to further actions along similar lines? Recall self-

However, in real life, perception of choice usually is involved when we act. Self-

266

Another aspect of this paradigm that Milgram noted was that, in the studies with the highest levels of obedience, the participants had to tell the authority figure to his face that they refused to continue. Milgram posited that it is very difficult to defy a legitimate authority figure in this manner. Why? Milgram based his explanation on Erving Goffman’s analysis of self-

SOCIAL PSYCH out in the WORLD

Death in the Voting Booth

Death in the Voting Booth

In a follow-

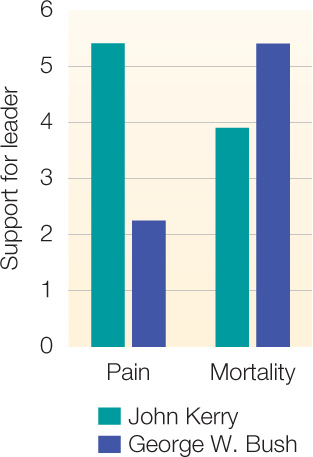

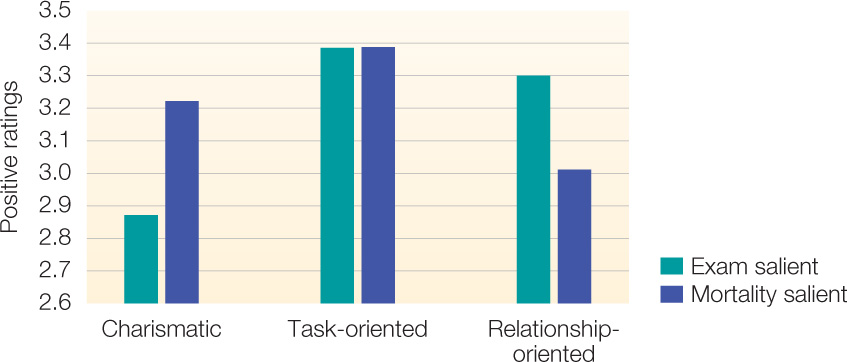

FIGURE 7.9

The effects of mortality salience and leader characteristics on liking for a leader

When reminded of mortality, participants’ attitudes become much more favorable to a charismatic candidate for governor who promotes the greatness of the state.

[Data source: Landau et al.(2004)]

Although research has shown that people’s awareness of death can influence decisions in hypothetical elections, would reminders of death affect voting in a real political context? Landau and colleagues (2004) proposed that the dramatic spike in support for President George W. Bush and his policies following the deadly terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 suggested that it would. On September 10, 2001, polls showed Bush’s approval rating was at a dismal 49% (Pyszczynski et al., 2003). On September 13, his approval rating soared to 94%. Bush fit the characteristics of a charismatic leader in that he exuded calm self-

The Role of Charisma in the Rise to Power

So now we know that people are likely to obey beyond what our intuitions would lead us to believe. And we know some reasons why people obey. Understanding that humans have a proclivity to obey is one aspect of explaining the historical phenomenon of Nazi Germany. But another major aspect is understanding whom we obey. Obviously we obey people in various authoritative roles whom the culture tells us to obey. One important set of such individuals is the people we view as leaders. But the remaining question regarding the Nazi phenomenon is, How in the world did someone as vile as Adolf Hitler become the revered leader of Germany?

267

The existential perspective provides some answers. According to Ernest Becker (1973) and the terror management theory (e.g., Greenberg et al., 2008), new leaders emerge when the prevailing worldview of a culture no longer provides its members with compelling bases of meaning and self-

Charismatic leader

An individual in a leadership role who exhibits boldness and self-

APPLICATION: Historical Perspectives

|

APPLICATION: |

| Historical Perspectives |

This terror management analysis seems to fit many historical instances in which charismatic leaders, including Hitler, emerge and rise to great power. Germany was humiliated and economically devastated by the loss of World War I and the signing of the very disadvantageous Treaty of Versailles in 1919. In the wake of all these events, it did not feel good to be a German. During the early 1920s, Hitler began his crusade to oust the ruling government and rid Germany of what he called the impure evil others—

268

Similar contributing factors have been observed in the rise of admired leaders as well as vilified ones. For example, the Indian leader Mohandas K. (“Mahatma”) Ghandi engaged in acts of nonviolent resistance and espoused a philosophy of national empowerment in his early efforts to free India from subjugation to Great Britain. He became the leader of this large nation during its process of liberation from British control without formal election to any official government position. Similar analyses can be applied to the emergence of leaders of small cults, such as the Reverend Jim Jones, and the leaders of large cults, such as the Reverend Sun Yung Moon, as well as many other religious and political leaders.

FIGURE 7.10

The effects of mortality salience on liking for the 2004 presidential candidates

Reminders of mortality increased support, and intentions to vote for George W. Bush; however, they had the opposite effect for Senator John Kerry.

[Data source: Cohen et al. (2004)]

Of course, all of these historical phenomena are complex and involve many potential causal factors that are difficult to disentangle. However, social psychologists have studied the terror management analysis of the emergence of charismatic leaders by testing whether reminders of mortality increase the appeal of charismatic leaders. In a study by Cohen and colleagues (2004), half the participants were led to think about their own deaths. The other half were primed with another aversive topic, an upcoming exam. Participants then read campaign statements purportedly written by three political candidates in a hypothetical gubernatorial election. On the basis of research on leadership styles (Ehrhart & Klein, 2001), each candidate was modeled to fit the profile of either a charismatic, task-

Looking at FIGURE 7.10, you can see that after people thought about an upcoming exam, their attitudes toward the charismatic leader were less favorable than to the other two leaders. However, after people thought about their own deaths, they were significantly more attracted to the charismatic leader. This effect was also reflected in their voting intentions. Whereas exam-

269

SECTION review: Obedience to Authority

| In Milgram’s studies, the level of obedience went far beyond what anyone predicted and made it clear that the proclivity to obey authority is a potential danger in any culture and in any era. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Variables that influence obedience

|

Who obeys |

We obey because: |

The role of charisma |

CONNECT ONLINE:

Check out our videos and additional resources located at: www.macmillanhighered.com/