8.3 Characteristics of the Message

Attitudes are influenced not only by the source of the message but also by the content and style of the message itself as it appeals to both our minds and our feelings. Here we consider some characteristics of the message, including approaches you can take to enhance your own ability to persuade.

Thinking Differently: What Changes Our Minds

Argument Strength

Earlier we said that when people take the central route to persuasion, their attitudes are influenced primarily by the strength of the arguments. But what makes an argument strong or weak?

First, to be strong a message needs to be comprehensible. For example, participants in one study were more convinced by arguments arranged in a logical order than they were by the same arguments presented in a jumbled order (Eagly, 1974).

Argument strength is also influenced by the length of the message. If you want to persuade people, should you present them with a long communication that contains lots of arguments, or a short one? There is no simple answer. If the audience takes the central route, message length can either increase and decrease persuasion. On the one hand, a longer message can be more persuasive if it contains many supportive arguments rather than a few (Calder et al., 1974). On the other hand, if you try to increase the length of a message artificially by adding weak arguments or repeating the same arguments, an attentive audience may become irritated at the message and reject it (Cacioppo & Petty, 1979). Also, people’s cognitive resources allow them to think about and remember only so many arguments in a given time span. The more arguments you present, the less able the audience is to think about and rehearse those arguments, and the fewer they will remember (Eagly, 1974). As a result, longer messages with arguments of varying quality can be less persuasive than messages containing only a few, highly convincing arguments (Anderson, 1974; Harkins & Petty, 1987). Sometimes less is more.

282

If the audience is taking the peripheral route, longer messages tend to be more persuasive than shorter ones (Petty & Cacioppo, 1984; Wood et al., 1985). Why? Imagine that you are reading a newspaper editorial advocating increasing the local property tax. You notice that it lists 19 bullet-

Confident Thoughts About the Message

We have seen that when people take the central route, they are not passively receiving a persuasive message. Rather, they are actively elaborating on the message, thinking carefully about its central claims and comparing that information with their prior knowledge of the topic. According to the cognitive response approach to persuasion (Greenwald, 1968), their attitudes will be influenced not only by what they think about the message but also by how confident those thoughts feel (Petty et al., 2002).

Cognitive response approach to persuasion

Occurs when people’s attitude is influenced not only by what they think about the message but also by their confidence in those thoughts and beliefs.

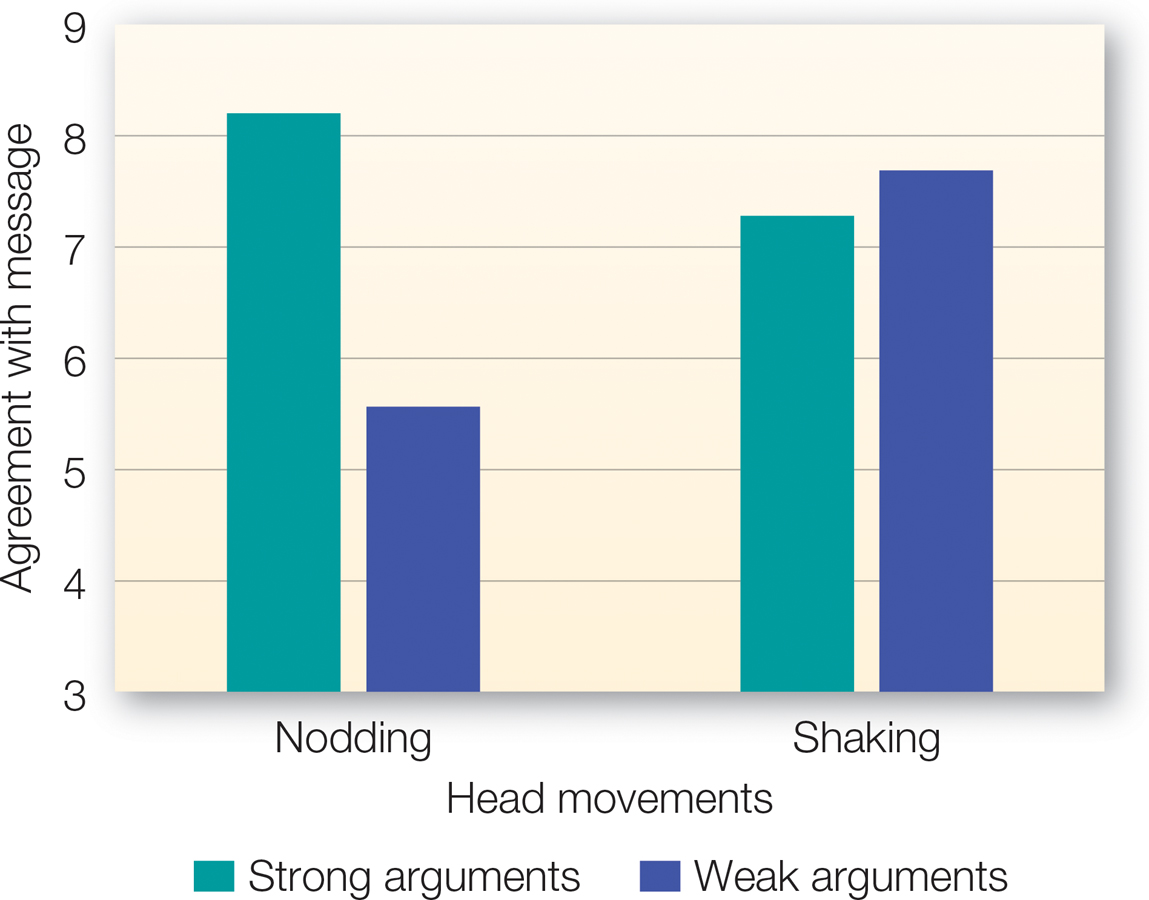

FIGURE 8.5

Nod If You Agree

Nodding is a subtle signal of endorsement and can magnify your response to an argument by making you more confident of your (either positive or negative) opinion. In this study, participants who were instructed to nod their heads while listening to a persuasive message were more likely to agree with the message if the arguments were strong rather than weak. But if they were instructed to shake their heads from side to side, they were not affected by the strength of the argument.

[Data source: Briñol & Petty (2003)]

People often step back and think about their own thoughts—

Briñol and Petty (2003) hypothesized that if people nod their own heads while generating thoughts about a message, those thoughts would feel more valid, and would therefore strongly guide their attitudes. To test this hypothesis, they had college students put on a pair of headphones and listen to a speech advocating that students be required to carry personal identification cards. Participants were also told that the headphones were specially designed for use during exercise and other bodily movement. Thus, to test the headphones’ performance, participants were asked to move their heads while listening to the speech. Half the participants were asked to move their heads up and down (as if nodding “yes”); the other participants were asked to shake their heads from side to side (as if saying “no”). Even though this head-

Statistical Trends Versus Vivid Instances

Persuasive messages often feature statistics (“Four in five dentists agree….”) or vivid examples (“Jared lost weight at Subway!”). Which is more persuasive? Consider this scenario: You’re wondering which city to move to after graduation. After comparing statistics such as per capita crime rates and housing market trends, you tentatively decide on Chicago. But soon after, a friend tells you in vivid detail that her purse was stolen in Chicago, and she’s not likely to return. How much will this one person’s experience influence your attitudes? Rationally speaking, it shouldn’t: That person’s experience is one out of millions. Nevertheless, a single vivid example can have a surprisingly strong impact on attitudes, even when it conflicts with one’s knowledge of what is generally or statistically true. Why? Because a vivid instance entices the audience to connect the message to their own experience and emotions (Strange & Leung, 1999). In this example, your friend’s experience may trigger your own memories of times you felt unsafe in a big city or of other negative things you’ve heard about Chicago.

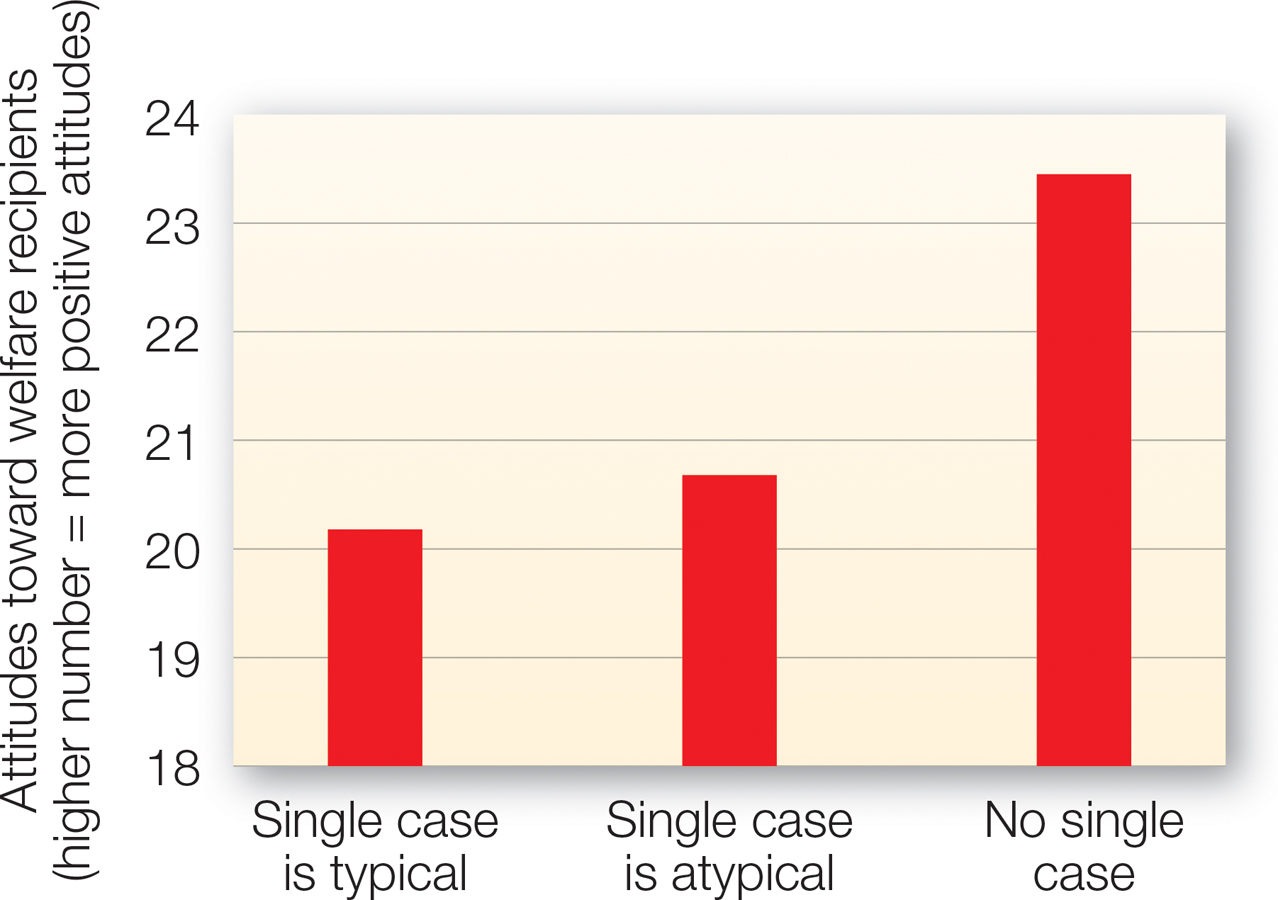

FIGURE 8.6

The Persuasive Power of Anecdotes

In this study, a single vivid story of a person who abuses the welfare system decreased the positivity of people’s attitudes toward welfare. This striking effect occurred regardless of whether people were told that this person was typical or atypical of welfare recipients.

[Data source: Hamill et al. (1980)]

283

In one demonstration of this, Hamill and colleagues (1980) had participants read an article that described in vivid detail how a welfare recipient had spent the last couple years abusing the welfare system by making dishonest purchases and neglecting her adult responsibilities. After reading the article, some participants (those in the “typical” condition) were told that the woman described in the article was typical of welfare recipients and had been receiving welfare for an average length of time. In contrast, participants in the “atypical” condition were told the opposite—

Afterward, all participants reported their attitudes toward the entire population of welfare recipients, answering questions such as, “How hard do people on welfare work to improve their situations?” As you can see in FIGURE 8.6, participants exposed to the vivid description of just one person abusing the welfare system reported less favorable attitudes toward the entire population of welfare recipients than did those who did not read the description. Also important, it didn’t matter whether participants were told explicitly that the described woman was typical or atypical of welfare recipients. A vivid description of a single case can have a powerful influence on attitudes, even when it’s not representative of a larger population of people or experiences. This is an important point to keep in mind when others attempt to persuade you: A single personal example or event can grab hold of your attention, but it’s important to think about whether that single example is representative of the broader reality.

The Size of the Discrepancy

Imagine you were asked by your local newspaper to write an editorial article encouraging people to conserve natural resources. Your goal is to change people’s attitudes, and, you hope, their behavior, but how extreme should your position be? You could advocate that people make large lifestyle changes such as walking to work every day rather than driving. This is a gamble: If people are persuaded, then you’ve successfully changed their attitudes to a significant extent, but you run the risk of turning people off completely or being dismissed as radical. On the other hand, if you advocate for smaller lifestyle changes, such as using fewer water bottles, people may be more likely to go along with you, but you will always wonder: “Could I have had a greater influence if I had pushed them outside their comfort zone a little farther than I did?”

The issue here has to do with the discrepancy between the position advocated in a message and the audience’s preexisting attitudes. Let’s consider what goes on in the audience’s heads when they encounter a discrepant message. We know that people are strongly motivated to be right—

284

However, another way that people can reduce their discomfort is to derogate the source of the message. If an audience discounts a communicator’s expertise or trustworthiness, they can write off his or her message and keep their existing attitudes intact. In line with this intuition, research shows that as the size of the discrepancy increases, attitude change increases—

So what gives? Should you start with a really extreme position or not? To make sense of these seemingly contradictory findings, Aronson and colleagues (1963) proposed that the key factor is the credibility of the source. If the communicator is seen as highly credible—

The Order of Presentation: Primacy Versus Recency

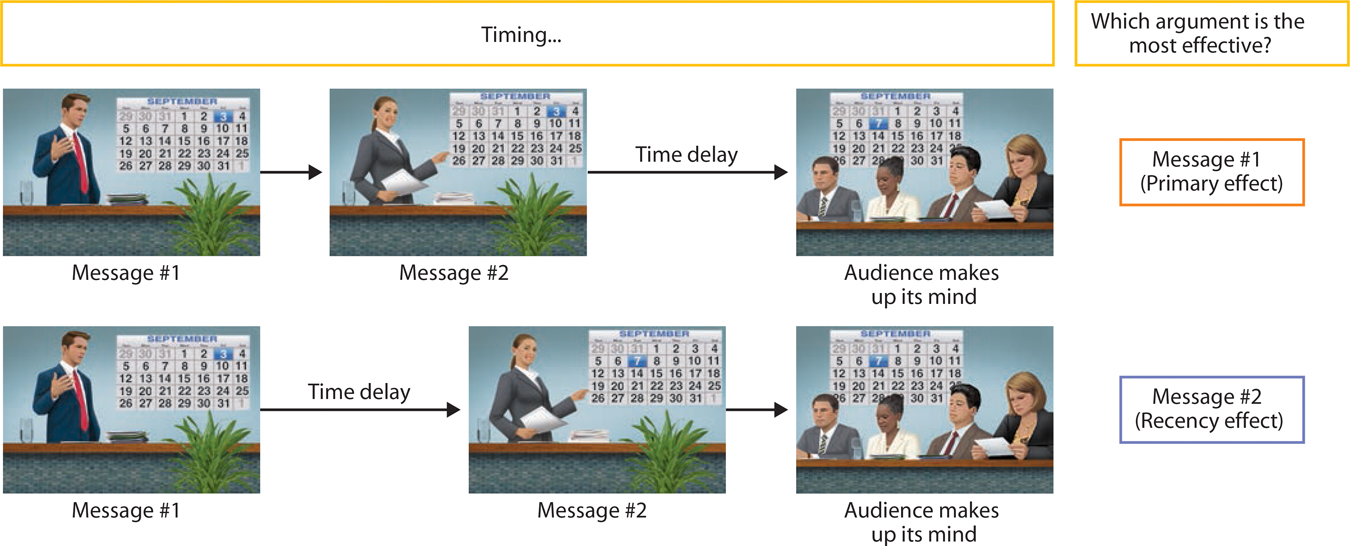

FIGURE 8.7

Getting Time on Your Side

When making a persuasive appeal, it is better to go first if the audience will be making its decision after hearing both arguments and then taking a break. But it is better to go last if the audience will make their decision immediately after hearing your presentation.

Imagine it is early December, with the holidays approaching, and you get a phone call in which you learn that you’re one of two final applicants for a great job. The employer asks if you would like to be the first or the second person interviewed. During the interview you’ll be given time to make your case as to why the employers should hire you rather than the other applicant. Other things being equal, should you opt to go first or second?

Perhaps your intuition tells you that the person who is interviewed first will be the more persuasive, because she has the chance to make the critical first impression and get the employers on her side early on. In this way, she insures that the other applicant will not only have to offer a good argument for her own candidacy but she also will have to counter-

Research shows that both intuitions are correct: Arguments presented first and last each can provide the edge you want—

If there is no delay separating the two messages, and if there is a considerable delay between the end of the second message and the audience’s response, then the first message will be more persuasive than the second (other things being equal, of course). This is called the primacy effect. What accounts for this effect? When little time elapses between the two messages, the first message is still fresh in audience members’ minds when they receive the second message. As a result, they have more difficulty learning the arguments in the second message. As we discussed earlier, arguments that are difficult to comprehend are less persuasive.

Primacy effect

Occurs when initially encountered information primarily influences attitudes (e.g., the first speaker in a policy debate influences the audience’s policy approval).

285

In contrast, if there is a time delay separating the two messages, and if the audience makes up its mind immediately after the second message, then the second message will be more persuasive than the first. This is called the recency effect. Under these conditions, the first message does not interfere so much with the audience’s ability to learn the second argument. More important, the second argument is fresher in the audience’s memory when it makes up its mind.

Recency effect

Occurs when recently encountered information primarily influences attitudes (e.g., a commercial viewed just before shopping influences a shopper’s choices).

So the answer to which of the interview positions will have the advantage in the hiring decision is, “It depends.” If the applicants are to interview back to back with no delay (i.e., before the holiday break), and if the employers are going to take some time after the second interview to think over the arguments before deciding (i.e., after the holidays), then the primacy effect will be dominant, and the first interview will be the more persuasive. But if there is to be a long break between the two interviews (i.e., one before the holiday and one after), and the employers are going to make their decision immediately after the second interview, then the recency effect will be dominant, and the second interview will be the more persuasive.

Emotional Responses to Persuasive Messages

Persuading people involves changing their thoughts, but it also involves changing how they feel about something at a deeper, “gut” level. Persuasive messages are more effective if they get the audience to associate a position or a product with positive feelings and the avoidance of negative feelings. This can be accomplished in a number of ways. Generally, this below-

Repetition and Familiarity

FIGURE 8.8

1984

The Ministry of Truth, the governing body of the dystopian world George Orwell sets up in his book 1984, saturates its citizens with intense propaganda campaigns to indoctrinate them with officially acceptable attitudes. Which persuasion techniques does Big Brother use?

[Alamy]

One of the most basic ways that persuasive messages get the audience to feel positive about a position or brand is through repetition. If you have ever watched the same TV channel for more than an hour, you probably noticed that the same commercials are repeated over and over. One advantage of repeating messages is that it can help the audience to comprehend messages that might be complex. Second, even if the message is not difficult to comprehend, seeing or hearing a message over and over again increases the accessibility of a product or position in the audience’s memory. This was illustrated in George Orwell’s dystopian novel 1984 (see FIGURE 8.8). In the novel, Big Brother—

286

Repeatedly exposing consumers to a persuasive message may have another benefit for advertisers. Research on the mere exposure effect shows that the more we are exposed to a novel stimulus, the more we tend to like it. Zajonc (1968) first studied this phenomenon by showing American participants pictures of Chinese characters, a novel thing for most Americans. Participants rated those characters that they viewed many times as being more aesthetically pleasing than characters that they hadn’t seen or had seen only a few times. The mere exposure effect occurs even when people are unaware of having been frequently exposed to a stimulus. In fact, research suggests that the mere exposure effect actually might be strongest when exposure happens outside of awareness (Bornstein, 1989). The more often people unconsciously perceive the stimulus, the more they tend to like it, prompting Zajonc (1980) to claim that “preferences need no inferences.”

Mere exposure effect

Occurs when people hold a positive attitude toward a stimulus simply because they have been exposed to it repeatedly.

The best general explanation for the mere exposure effect is that the more people are exposed to a neutral stimulus, the more familiar it feels, and people generally prefer the familiar to the unfamiliar. Debate continues regarding why the familiar is preferred, but there are two likely explanations (Chenier & Winkielman, 2007). First, as novel stimuli become familiar, they seem less strange and safer. Second, familiar stimuli are easier to perceive and grasp fully.

Think ABOUT

The mere exposure effect has been demonstrated for a host of different types of stimuli, including people, music, and geometric figures, but it has its limits. For one, the effect generally plateaus at around 20 exposures; further exposures have only minimal impact on attitudes (Chenier & Winkielman, 2007). Also, the effect does not hold for initially disliked stimuli. Furthermore, the complexity of the stimulus influences the optimal number of exposures (Cacioppo & Petty, 1979). Simpler stimuli sometimes may be liked quicker, but the liking will also turn to boredom more quickly. Think of songs that you hear on a Pandora station and initially enjoy, but after a few weeks of hearing the station playing the song all the time, you want to stuff your ears with cotton. Another exception is captured by the idea of attitude polarization (see chapter 9) (Tesser & Conlee, 1975). Research demonstrating the mere exposure effect focuses on changing people’s attitudes toward something that is initially neutral. But research on attitude polarization shows that if we dislike something initially, we dislike it even more if we are exposed to it over and over.

287

Linking the Message to Positive Stimuli

Another way to get audience members to feel positive about a message is to get them to associate the product or position advocated in the message with stimuli that they already have positive attitudes about, even if the topic of the message and the other stimuli are not inherently related. This was seen, for example, in a recent commercial for the Dodge Charger car that depicted George Washington driving a Charger straight into a crowd of British soldiers as they cower in terror. The narrator intones, “Here are a couple things America got right: cars and freedom.” In this way, the advertiser hopes to get American viewers to link the Charger with ideas that they presumably already like, including America, freedom, and masculine overpowering of sniveling weaklings: Indeed, the tongue-

Repetition also can be very useful in creating these associations. This is because repetition enhances learning, whether through classical conditioning, operant conditioning, or social learning. Classical conditioning occurs when an initially neutral stimulus (the conditioned stimulus) becomes associated with another stimulus that is inherently pleasant or unpleasant (the unconditioned stimulus). When a message repeatedly pairs an object or recommendation with an unconditioned stimulus that already triggers a positive response (e.g., sex, food, cute babies), the topic of the message will be more likely to trigger that same positive response (Staats & Staats, 1958).

In one study demonstrating the influence of classical conditioning on attitudes, Razran (1940) presented participants with slogans such as “Workers of the world, unite.” These slogans were presented repeatedly while participants were either enjoying a free lunch (an unconditioned positive stimulus), inhaling unpleasant odors (an unconditioned negative stimulus), or in a neutral setting. As you might expect, participants formed more positive attitudes toward the slogans when they were paired with the free lunch and more negative attitudes toward the same slogans when they were paired with unpleasant odors. Interestingly, the participants were not consciously aware of which slogans were associated with the lunch, the odors, or the neutral conditions. This demonstrated that classical conditioning is a very basic way that people learn to associate the content of the persuasive message with positive feelings.

Operant conditioning is another form of learning that can be used to link a message with positive feelings. In this type of learning, people engage in a behavior and, if rewards follow, they are more likely to engage in that behavior again. One recent marketing trend that harnesses operant conditioning is to associate the purchase of a product with philanthropic rewards. Although these campaigns haven’t always been successful, the assumption is that by buying the product, you feel better about yourself, thereby reinforcing the behavior. Some recent examples:

Tom’s Shoes: For every pair you buy, Tom’s Shoes will donate a pair to children in need.

Starbuck’s Ethos Water Fund: Every bottle purchased results in a contribution to clean-

Pepsi’s Refresh Project: Purchases of Pepsi products helped PepsiCo give away millions in grants each month to fund philanthropic projects.

288

KFC’s Buckets for a Cure campaign: With every purchase of a pink bucket of fried chicken, KFC donated 50 cents to breast cancer research.

Snickers’s “Bar Hunger” program: With every purchase of a Snickers bar, the company will donate a meal to someone in need.

Social learning plays a role as well. When people watch a character in a television ad use a product and get rewarded for doing so, the observer vicariously associates the product with a good outcome and will be more likely to use the product herself. For instance, if a commercial depicts a man buying a certain brand of tequila and thereafter ten supermodels instantly focus their lustful gaze on him, the implicit message is that buying this brand of tequila produces positive attention.

Cognitive Balance and Positive Associations

The learning perspectives we just covered rely on repetition to get the audience to pair an object or position mentally with another positive stimulus or reward. Fritz Heider’s balance theory gives us another way of understanding how messages can link products or positions with positive things effectively, even without repeated exposure. Heider (1946) posited that people have a strong tendency to maintain consistency among their thoughts (an idea that should be familiar after our discussion of cognitive dissonance in chapter 6). Consider this example: If it is the case that (a) you like your friend; (b) your friend likes ballroom dancing; and (c) you like ballroom dancing, then all these cognitions are consistent. But if it is the case that you hate ballroom dancing, there would be inconsistency among your thoughts, leading you to wonder about your friend, “How could someone so cool like something so lame?” To bring your cognitions back in harmony with each other—

The mere exposure effect is one reason that corporate sponsors pay gargantuan sums for repeated presentations of their logo, spokesperson, or jingle. How many articles of clothing do you own that clearly display a specific brand name? Another subtle method of repeated exposure is product placement. As we discuss in more detail later on, this essentially involves having a product appear “naturally” in everyday contexts in movies and television shows (e.g., having various characters in a movie drinking Coca-

Balance theory

Theory proposing that the motivation to maintain consistency among one’s thoughts colors how people form new attitudes and can also drive them to change existing attitudes.

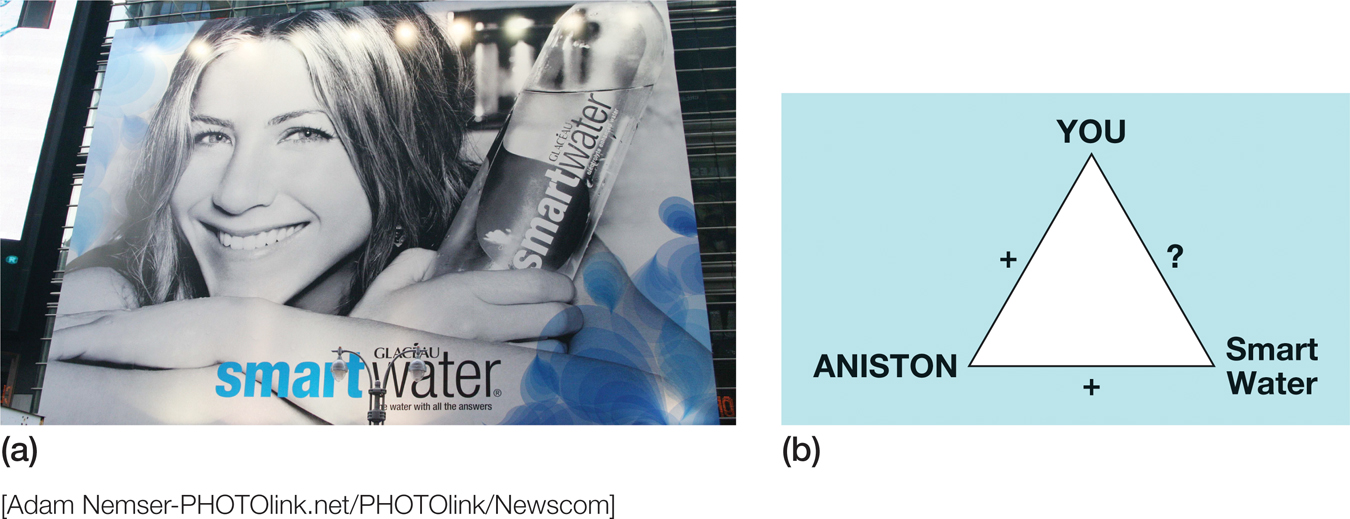

FIGURE 8.9

Balance Theory

According to Heider’s balance theory, if you like Jennifer Aniston and she likes Smart Water, than you are inclined to like Smart Water, too.

[Adam Nemser-

This perspective helps to explain why the magazine ad in FIGURE 8.9a might be effective. The ad assumes that you, as the magazine reader, already have a positive attitude toward Jennifer Aniston (hence the plus sign connecting you and Aniston in FIGURE 8.9b). The ad informs you that Aniston is positively inclined toward Smart Water. This leaves only your relation to Smart Water undetermined. According to balance theory, the audience would experience an internal pressure to evaluate Smart Water positively so that they can maintain a harmonious state in which all the elements (themselves, Aniston, Smart Water) are consistent with each other. If people were not naturally inclined to prefer balanced over imbalanced relations between their thoughts, then we wouldn’t expect them to feel any motivation to like Smart Water, because they would be perfectly comfortable if some of the elements in this system didn’t quite fit together.

Positive Mood

Another way to create positive feelings toward a message is to deliver it when people are in a good mood. In a classic study by Janis and colleagues (1965), participants read a series of persuasive messages on topics such as the armed forces and 3-

289

Negative Emotions

Of course, not all persuasive messages try to create positive emotions; some try to persuade the audience that by doing something or acquiring something, they can avoid negative consequences or punishments. For example, a message might pitch a product as providing relief from a painful or embarrassing social encounter or as reducing one’s harmful impact on the environment. In these cases, the designer of the message is hoping to arouse negative emotions and then offer recommendations for assuaging your concern. Most commonly, these kinds of messages try to evoke fear in the audience. Your current author recently saw a pamphlet (and, yes, read it!) in the optometrist’s office titled, “Your Eyes Are Under Attack!”

Sometimes fear works, leading to more attitude and behavioral change. Banks and colleagues (1995) found that middle-

But fear also can backfire. Janis and Feshbach (1953) found that a message was less effective at persuading the audience to practice improved oral hygiene if it used fear-

So what makes the difference? Leventhal (1970) proposed that arousing fear on its own is not enough to persuade people. When people are told simply that they will suffer some threatening outcome, they feel distressed or helpless, and they often tune out entirely. But if you provide them with a clear means of protecting themselves from that threatening outcome, then they are more likely to be persuaded. That is, fear-

In one study testing this possibility, Leventhal and colleagues (1965) found that participants were more likely to follow the recommendation of a health message and get a tetanus shot if they were exposed to a fear-

290

APPLICATION: Is Death Good for Your Health

|

APPLICATION: |

| Is Death Good for Your Health |

So far we’ve assumed that fear-

This research suggests the interesting possibility that arousing fears about death may have completely opposite effects on people’s health attitudes and behavior. On the one hand, people are motivated to avoid threats to their survival, so bringing thoughts of death to mind might motivate them to avoid potentially lethal risks, such as drunk driving (Jessop et al., 2008). On the other hand, increasing people’s death awareness might motivate them to enhance their self-

Goldenberg and Arndt (2008) proposed that a key factor is the degree to which death-

In one study supporting this analysis, undergraduates were asked to take part in a consumer marketing study (Routledge et al., 2004). All the participants had earlier indicated that having a radiant tan helped to bolster their feelings of self-

SOCIAL PSYCH out in the WORLD

This Is Like That: Metaphor’s Significance in Persuasion

Many times, we come across persuasive messages that, strictly speaking, make no sense. Consider the statement made by opponents of a mandatory seatbelt law being contested in California some years ago: “We don’t want Governor Deukmejian sitting in our bathtub telling us to wash behind our ears.”

This is an example of a metaphoric message, a communication that compares one type of thing with another type of thing. Beginning with Aristotle, scholars have noted metaphor’s power to persuade. Returning to the bathtub metaphor above, even though people know that enacting a seat belt law does not literally mean having the governor in the bathtub with them, hearing the bathtub metaphor guides them to think about the seatbelt law as the same type of thing—

Other common metaphoric messages try to change how people understand social problems and thus evaluate certain solutions. Many real-

Do such messages work? To find out, Thibodeau and Boroditsky (2011) asked participants to read different stories about a city with a serious crime problem. For some participants, crime was compared with a “beast” that was “preying upon” the innocent citizens of the town. For other participants it was described as a “disease” that “plagued” the town. After participants compared crime with a wild animal, they were more likely to generate solutions based on increased enforcement (e.g., calling in the National Guard, imposing harsher penalties). In contrast, participants given the virus analogy strongly preferred solutions that were more diagnostic and reform oriented (e.g., finding the root cause of the crime wave, improving the economy). In other words, the solutions that participants generated to solve the crime problem were consistent with the metaphors they read: if crime was like a beast, it must be controlled, but if it was like a disease, then it must be treated.

291

Metaphoric messages change attitudes, but can they change behavior? Maybe you recall seeing warning videos that are sometimes played before a movie. These videos aim to provide a lesson in the legality of downloading movies from torrent of web sites on the Internet. The words “You wouldn’t steal a car” appear on the screen, followed by a dramatic reenactment of a car theft. Then, “You wouldn’t steal a purse.” After reminding you of other objects you presumably do not intend to steal, the message concludes: “Downloading pirated films is stealing.” Pilfering a woman’s purse and downloading a pirated film are obviously similar situations in some respects, but they differ in others (e.g., the woman is left without the purse, whereas the movie’s owner still has it). Given what you’ve learned about social psychology research, how would you design an experiment to test whether this metaphor changes people’s behavior?

292

SECTION review: Characteristics of the Message

|

Characteristics of the Message |

|

Attitudes are influenced by the content and style of the message. |

||

|---|---|---|

|

What changes our minds Comprehensible messages. Confident thoughts about the message. Vivid instances that connect with personal experience. A position highly discrepant from prior attitudes (given a credible source). Order in which competing arguments are presented as they relate to the timing of the overall situation. |

What creates an effective emotional response Repetition and familiarity. Learned associations with positive stimuli. The need to maintain consistent ideas about related people or things. Positive mood. Use of fear to avoid negative consequences if paired with strategies to reduce the negative consequences. |

Health application Thoughts of death can motivate people to maintain healthy behaviors. Unconscious thoughts of death create the need to boost self- |