The Four Major Research Perspectives

There are four major research perspectives—biological, cognitive, behavioral, and sociocultural. It's important to understand that these perspectives are complementary. The research findings from the major perspectives fit together like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle to give us a more complete picture. No particular perspective is better than the others, and psychologists using the various perspectives work together to provide a more complete explanation of our behavior and mental processing.

The best way to understand how the major research perspectives differ is to consider the major goal of psychologists—to explain human behavior and mental processes. To explain means to know the causes of our behavior and mental processes. To facilitate your understanding of these perspectives, I discuss them in two different pairs based on the type of causal factors that they emphasize—internal factors or external factors. The biological perspective and the cognitive perspective focus on causes that stem from within us (internal factors); the behavioral perspective and the sociocultural perspective focus on causes that stem from outside us (external factors). We'll also briefly consider developmental psychology, a research field that provides a nice example of how these perspectives complement one another.

Perspectives Emphasizing Internal Factors

The biological perspective and the cognitive perspective focus on internal factors. In the case of the biological perspective, our physiological hardware (especially the brain and nervous system) is viewed as the major determiner of behavior and mental processing. The genetic and evolutionary bases of our physiology are also important. In contrast, for the cognitive perspective, the major explanatory focus is on how our mental processes, such as perception, memory, and problem solving, work and impact our behavior. To contrast this perspective with the biological perspective, you can think of these mental processes as the software, or programs, of the brain (the wetware, the biological corollary to computer hardware).

The biological perspective.

We are biological creatures; therefore, looking for explanations in terms of our biology makes sense. Biological psychologists look for causes within our physiology, our genetics, and human evolution. They argue that our actions and thoughts are functions of our underlying biology. Let's consider an example of what most people would term a “psychological” disorder, depression. Why do we get depressed? A biological psychologist might focus on a deficiency in the activity of certain chemicals in the nervous system as a cause of this problem. Therefore, to treat depression using this perspective, the problem with the chemical deficiency would have to be rectified. How? Antidepressant drugs such as Prozac or Zoloft might be prescribed. These drugs increase the activity of the neural chemicals involved, and this increased activity might lead to changes in our mood. If all goes well, a few weeks after beginning treatment, we begin to feel better. Thus, our mood is at least partly a function of our brain chemistry. Of course, many nonbiological factors can contribute to depression, including unhealthy patterns of thinking, learned helplessness, and disturbing life circumstances. It's important to remember that employing psychology's complementary perspectives in addressing research and clinical issues provides the most complete answer.

3

In addition to the impact of brain chemistry, biological psychologists also study the involvement of the various parts of the brain and nervous system on our behavior and mental processes. For example, they have learned that our “eyes ” are indeed in the back of our head. Biological psychologists have found that it is the back part of our brain that allows us to see the world. So, a more correct expression would be that “our eyes are in the back of our brain. ” The brain is not only essential for vision, but it is also the control center for almost all of our behavior and mental processing. In Chapter 2, you will learn how the brain manages this incredibly difficult task as well as about the roles of other parts of our nervous system and the many different chemicals that transmit information within it.

The cognitive perspective.

Cognitive psychologists study all aspects of cognitive processing from perception to the higher-level processes, such as problem solving and reasoning. Let's try a brief exercise to gain insight into one aspect of our cognitive processing. I will name a category, and you say aloud as fast as you can the first instance of that category that comes to mind. Are you ready? The first category is FRUIT. If you are like most people, you said apple or orange. Let's try another one. The category is PIECE OF FURNITURE. Again, if you are like most people, you said chair or sofa. Why, in the case of FRUIT, don't people say pomegranate or papaya? How do we have categories of information organized so that certain examples come to mind first for most of us? In brief, cognitive research has shown that we organize categorical information around what we consider the most typical or representative examples of a category (Rosch, 1973). These examples (such as apple and orange for FRUIT) are called prototypes for the category and are retrieved first when we think of the category.

A broader cognitive processing question concerns how memory retrieval in general works. Haven't you been in the situation of not being able to retrieve information from memory that you know you have stored there? This can be especially frustrating in exam situations. Or think about the opposite—an event or person comes to mind seemingly out of the blue. Why? Even more complex questions arise when we consider how we attempt to solve problems, reason, and make decisions. For example, here's a series problem with a rather simple answer, but most people find it very difficult: What is the next character in the series OTTFFSS_? The answer is not “O. ” Why is this problem so difficult? The progress that cognitive psychologists have made in answering such questions about cognitive processing will be discussed in Chapter 5, on memory, and Chapter 6, on thinking and intelligence (where you can find the answer to the series problem).

Perspectives Emphasizing External Factors

Both the behavioral perspective and the sociocultural perspective focus on external factors in explaining human behavior and mental processing. The behavioral perspective emphasizes conditioning of our behavior by environmental events, and there is more emphasis on explaining observable behavior than on unobservable mental processes. The sociocultural perspective also emphasizes the influence of the external environment, but it more specifically focuses on the impact of other people and our culture as the major determiners of our behavior and mental processing. In addition to conditioning, the sociocultural perspective equally stresses cognitive types of learning, such as learning by observation or modeling, and thus focuses just as much on mental processing as observable behavior.

4

The behavioral perspective.

According to the behavioral perspective, we behave as we do because of our past history of conditioning by our environment. There are two major types of conditioning, classical (or Pavlovian) and operant. You may be familiar with the most famous example of classical conditioning—Ivan Pavlov's dogs (Pavlov, 1927/1960). In his research, Pavlov sounded a tone and then put food in a dog's mouth. The pairing of these two environmental events led the dog to salivate to the tone in anticipation of the arrival of the food. The salivary response to the tone was conditioned by the sequencing of the two environmental events (the sounding of the tone and putting food in the dog's mouth). The dog learned that the sound of the tone meant food was on its way. According to behaviorists, such classical conditioning can explain how we learn fear and other emotional responses, taste aversions, and many other behaviors.

Classical conditioning is important in determining our behavior, but behaviorists believe operant conditioning is even more important. Operant conditioning involves the relationship between our behavior and its environmental consequences (whether they are reinforcing or punishing). Simply put, if we are reinforced for a behavior, its probability will increase; if we are punished, the probability will decrease. For example, if you ask your teacher a question and he praises you for asking such a good question and then answers it very carefully, you will tend to ask more questions. However, if the teacher criticizes you for asking a stupid question and doesn't even bother to answer it, you will probably not ask more questions. Environmental events (such as a teacher's response) thus control behavior through their reinforcing or punishing nature. Both types of conditioning, classical and operant, will be discussed in Chapter 4. The point to remember here is that environmental events condition our behavior and are the causes of it.

The sociocultural perspective.

This perspective focuses on the impact of other people (individuals and groups) and our cultural surroundings on our behavior and mental processing. We are social animals; therefore other people are important to us and thus greatly affect what we do and how we think. None of us is immune to these social “forces. ” Haven't your thinking and behavior been impacted by other people, especially those close to you? Our coverage of sociocultural research will emphasize the impact of these social forces on our behavior and mental processing.

To help you understand the nature of sociocultural research, let's consider a famous set of experiments that attempted to explain the social forces operating during a tragic, real-world event—the Kitty Genovese murder in 1964 (Latan é & Darley, 1970). Kitty was returning home from work to her apartment in New York City when she was brutally attacked, raped, and stabbed to death with a hunting knife. The attack was a prolonged one in which the attacker left and came back at least three times. Kitty screamed and pleaded for help throughout the attack, but none was forthcoming. Some people living in the building heard her screams for help, but no one helped. Someone finally called the police, but it was too late. The attacker had fled, and Kitty was dead. Exactly how many people witnessed the attack and failed to help is not clear. Initially reported as 38 (Rosenthal, 1964), more recent analysis of the available evidence indicates that the number may have been much smaller (Manning, Levine, & Collins, 2007). Regardless, no one acted until it was too late. To explain why these people didn't help, researchers manipulated the number of bystanders present in follow-up experiments. Their general finding is called the bystander effect (and sometimes the Genovese Syndrome) —the probability of a victim receiving help in an emergency is higher when there is only one bystander than when there are many. In brief, other bystanders may lead us not to help. How do we apply this effect to the Kitty Genovese murder? The bystanders to the murder led each other not to help. Each felt that someone else would do something and that surely someone else had already called the police. This research, along with studies of other intriguing topics that involve social forces, such as why we conform and why we obey even when it may lead to destructive behavior, will be detailed in Chapter 9, on social psychology.

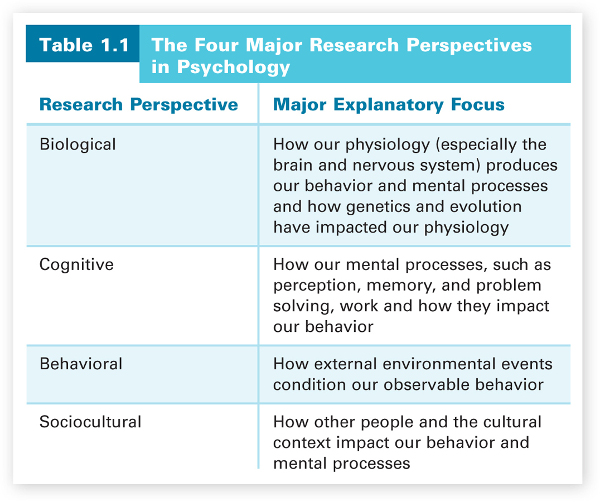

Now you have at least a general understanding of the four major research perspectives, summarized in Table 1.1. Remember, these perspectives are complementary, and, when used together, help us to gain a more complete understanding of our behavior and mental processes. Developmental psychology (the scientific study of human development across the lifespan) is a research area that nicely illustrates the benefits of using multiple research perspectives to address experimental questions. A good example is the study of how children acquire language. Initially, behavioral learning principles of reinforcement and imitation were believed to be sufficient to account for language acquisition. Although these principles clearly do play a role (Whitehurst & Valdez-Menchaca, 1988), most developmental language researchers now recognize that biology, cognition, and the sociocultural context are also critical to language learning (Pinker, 1994; Tomasello, 2003). Studies of the brain, for example, indicate that specific brain areas are involved in language acquisition. Research has also revealed that cognitive processes are important as well. For example, as children acquire new concepts, they learn the names that go with them and thus expand their vocabulary. In addition, it has been shown that the sociocultural context of language helps children to learn about the social pragmatic functions of language. For instance, they use a variety of pragmatic cues (such as an adult's focus of attention) for word learning. Thus, by using all four research perspectives, developmental researchers have gained a much better understanding of how children acquire language. We will learn in Chapter 7 (Developmental Psychology) that our understanding of many developmental questions has been broadened by the use of multiple research perspectives.

5

6

Subsequent chapters will detail the main concepts, theories, and research findings in the major fields of psychology. As you learn about these theories and research findings, beware of the hindsight bias (I-knew-it-all-along phenomenon) —the tendency, after learning about an outcome, to be overconfident in one's ability to have predicted it. Hindsight bias has been widely studied, having been featured in more than 800 scholarly papers (Roese & Vohs, 2012). It has been observed in various countries and among both children and adults (Blank, Musch, & Pohl, 2007). Research has shown that after people learn about an experimental finding, the finding seems obvious and very predictable (Slovic & Fischhoff, 1977). Almost any conceivable psychological research finding may seem like common sense after you learn about it. If you were told that research indicates that “opposites attract, ” you would likely nod in agreement. Isn't it obvious? Then again, if you had been told that research indicates that “birds of a feather flock together, ” you would probably have also agreed and thought the finding obvious. Hindsight bias works to make even a pair of opposite research conclusions both seem obvious (Teigen, 1986). Be mindful of hindsight bias as you learn about what psychologists have learned about us. It may lead you to think that this information is more obvious and easier than it actually is. You may falsely think that you already know much of the material and then not study sufficiently, leading to disappointment at exam time. The hindsight bias even works on itself. Don't you feel like you already knew about this bias? Incidentally, social psychology researchers have found that birds of a feather DO flock together and that opposites DO NOT attract (Myers, 2013).

Psychologists' conclusions are based upon scientific research and thus provide the best answers to questions about human behavior and mental processing. Whether these answers sometimes seem obvious or sometimes agree with common sense is not important. What is important is understanding how psychologists conduct this scientific research in order to get the best answers to their questions. In the next section, we discuss their research methods.

7

Section Summary

In this section, we learned that there are four major research perspectives in psychology. Two of them, the biological perspective and the cognitive perspective, focus on internal causes of our behavior and mental processing. The biological perspective focuses on causal explanations in terms of our physiology, especially the brain and nervous system. The cognitive perspective focuses on understanding how our mental processes work and how they impact our behavior. The biological perspective focuses on the physiological hardware, while the cognitive perspective focuses more on the mental processes or software of the brain.

The behavioral perspective and the sociocultural perspective emphasize external causes. The behavioral perspective focuses on how our observable behavior is conditioned by external environmental events. The sociocultural perspective emphasizes the impact that other people (social forces) and our culture have on our behavior and mental processing.

Psychologists use all four perspectives to get a more complete explanation of our behavior and mental processing. None of these perspectives is better than the others; they are complementary. Developmental psychology is a research field that nicely illustrates their complementary nature.

We also briefly discussed the hindsight bias, the I-knew-it-all-along phenomenon. This bias leads us to find outcomes as more obvious and predictable than they truly are. You need to beware of this bias when learning the basic research findings and theories discussed in the remainder of this text. It may lead you to think that this information is more obvious and easier than it actually is. It is important that you realize that psychologists have used scientific research methods to conduct their studies, thereby obtaining the best answers possible to their questions about human behavior and mental processing.

ConceptCheck | 1

Explain how the biological and cognitive research perspectives differ in their explanations of human behavior and mental processing.

Explain how the biological and cognitive research perspectives differ in their explanations of human behavior and mental processing.

Both of these research perspectives emphasize internal causes in their explanations of human behavior and mental processing. The biological perspective emphasizes the role of our actual physiological hardware, especially the brain and nervous system, while the cognitive perspective emphasizes the role of our mental processes, the “programs” of the brain. For example, biological explanations will involve actual parts of the brain or chemicals in the brain. Cognitive explanations, however, will involve mental processes such as perception and memory without specifying the parts of the brain or chemicals involved in these processes. Thus, the biological and cognitive perspectives propose explanations at two different levels of internal factors, the actual physiological mechanisms and the mental processes resulting from these mechanisms, respectively.

Explain how the behavioral and sociocultural research perspectives differ in their explanations of human behavior and mental processing.

Explain how the behavioral and sociocultural research perspectives differ in their explanations of human behavior and mental processing.

Both of these research perspectives emphasize external causes in their explanations of human behavior and mental processing. The behavioral perspective emphasizes conditioning of our behavior by external environmental events while the sociocultural perspective emphasizes the impact of other people and our culture on our behavior and mental processing. Thus, these two perspectives emphasize different types of external causes. In addition, the behavioral perspective emphasizes the conditioning of observable behavior while the sociocultural perspective focuses just as much on mental processing as observable behavior and on other types of learning in addition to conditioning.