7.1 Moral Development and Social Development

We develop cognitively and socially simultaneously, so these two types of development are difficult to separate. As Vygotsky stressed, cognitive development is best understood in its social context. In this section, we will discuss moral and social development, but we need to remember that it occurs simultaneously with cognitive development and is affected by it. Moral reasoning that involves both social and cognitive elements is a good illustration of this interactive development. For example, until a child moves away from egocentric thinking, it would be difficult for her to consider different perspectives when reasoning about the morality of a particular action. We begin our discussion of social development with a description of the major theory of moral development, Kohlberg’s stage theory of moral reasoning. Then, we examine early social development with a discussion of attachment formation and parenting styles followed by a discussion of one of the most important social developments in early childhood, theory of mind. We conclude with a description of Erik Erikson’s stage theory of social-personality development across the life span, from birth through late adulthood.

Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Reasoning

The most influential theory of moral reasoning is Lawrence Kohlberg’s stage theory (Kohlberg, 1976, 1984). Building on an earlier theory of moral reasoning proposed by Piaget (1932), Kohlberg began the development of his theory by following in Piaget’s footsteps, using stories that involved moral dilemmas to assess a child’s or an adult’s level of moral reasoning. To familiarize you with these moral dilemmas, consider Kohlberg’s best-known story—a dilemma involving Heinz, whose wife was dying of cancer. In brief, there was only one cure for this cancer. A local druggist had developed the cure, but he was selling it for much more than it cost to make and than Heinz could pay. Heinz tried to borrow the money to buy it, but could only get about half of what the drug cost. He asked the druggist to sell it to him cheaper or to let him pay the rest later, but the druggist refused. Out of desperation, Heinz broke into the druggist’s store and stole the drug for his wife. Given this story, the person is asked if Heinz should have stolen the drug and why or why not.

296

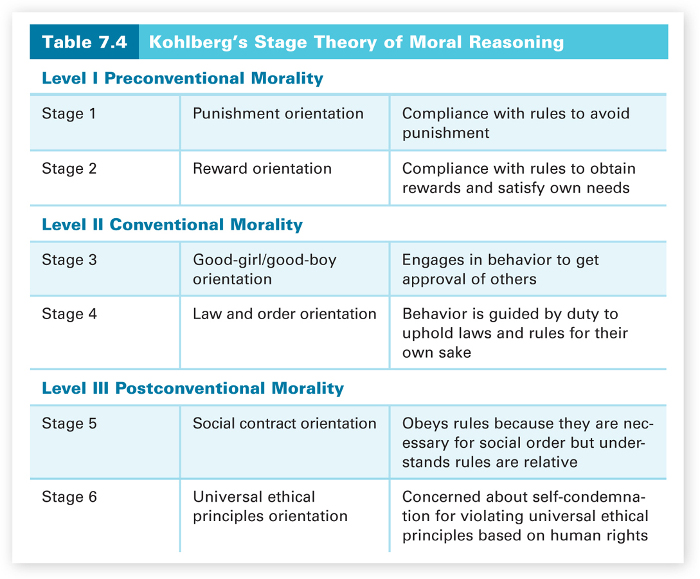

Using the responses to and explanations of this and other moral dilemmas, Kohlberg found three levels of moral reasoning—preconventional, conventional, and postconventional. These levels are outlined in Table 7.4. Each level has two stages. At the preconventional level of moral reasoning, the emphasis is on avoiding punishment and looking out for your own welfare and needs. Moral reasoning is self-oriented. At the conventional level, moral reasoning is based on social rules and laws. Social approval and being a dutiful citizen are important. At the highest level, the postconventional level, moral reasoning is based on self-chosen universal ethical principles, with human rights taking precedence over laws, and on the avoidance of self-condemnation for violating such principles.

It is important to point out that in determining a person’s level, it did not matter to Kohlberg whether the person answered yes or no to the dilemma. For example, in the Heinz dilemma, it did not matter whether the person said he should steal the drug or that he should not do so. The reasoning provided in the person’s explanation is what mattered. Kohlberg provided examples of such explanations for each level of reasoning. To understand how Kohlberg used these responses to the moral dilemmas, let’s consider sample Stage 4 rationales for stealing the drug and for not stealing the drug. The pro-stealing explanation would emphasize that it is Heinz’s duty to protect his wife’s life, given the vow he took in marriage. But it’s wrong to steal, so Heinz would have to take the drug with the idea of paying the druggist for it and accepting the penalty for breaking the law. The anti-stealing rationale would emphasize that you have to follow the rules regardless of how you feel and regardless of the special circumstances. Even if his wife is dying, it is still Heinz’s duty as a citizen to follow the law. If everyone started breaking laws, there would be no civilization. As you can see, both explanations emphasize the law-and-order orientation of this stage—if you break the law, you must pay the penalty.

297

Kohlberg proposed that we all start at the preconventional level as children and as we develop, especially cognitively, we move up the ladder of moral reasoning. The sequence is unvarying, but, as with Piaget’s formal operational stage, we all may not make it up to the last stage. That the sequence does not vary and that a person’s level of moral reasoning is age-related (and so related to cognitive development) has been supported by research.

Research also indicates that most people in many different cultures reach the conventional level by adulthood, but attainment of the postconventional level is not so clear (Snarey, 1985). There are other problems. First, it is important to realize that Kohlberg was studying moral reasoning and not moral behavior. As we will see in Chapter 9, on social psychology, thought and action are not always consistent. Ethical talk may not equate to ethical behavior. Second, some researchers have criticized Kohlberg’s theory for not adequately representing the morality of women. They argue that feminine moral reasoning is more concerned with a morality of care that focuses on interpersonal relationships and the needs of others than a morality of justice, as in Kohlberg’s theory. Similarly, critics have questioned the theory’s universality by arguing that the higher stages are biased toward Western values. In summary, Kohlberg’s theory has both support and criticism, but more importantly, it has stimulated research that continues to develop our understanding of moral development.

298

Attachment and Parenting Styles

As we have said before, humans are social creatures. Infants’ first social relationship—between them and their primary caregivers—is important and has been carefully studied by developmental psychologists (Bowlby, 1969). This lifelong emotional bond that exists between the infants and their mothers or other caregivers is formed during the first six months of life and is called attachment. Traditionally, the primary caregiver has been the infant’s mother, but times have changed; today the primary caregiver could be the mother, father, grandparent, nanny, or day care provider. Because attachment is related to children’s later development, it is also important to examine whether children who are put in day care at a young age are at a disadvantage in comparison to those who remain at home. Following a discussion of some of the early research on attachment, we will address this question. First, we consider the question of why the attachment forms. Is it because the caregiver provides food, and the attachment forms as a consequence of reinforcement?

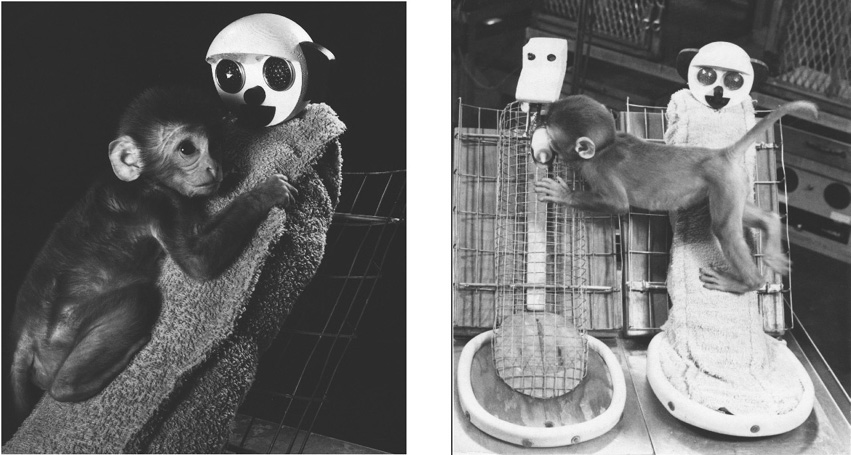

Attachment and Harlow’s monkeys.

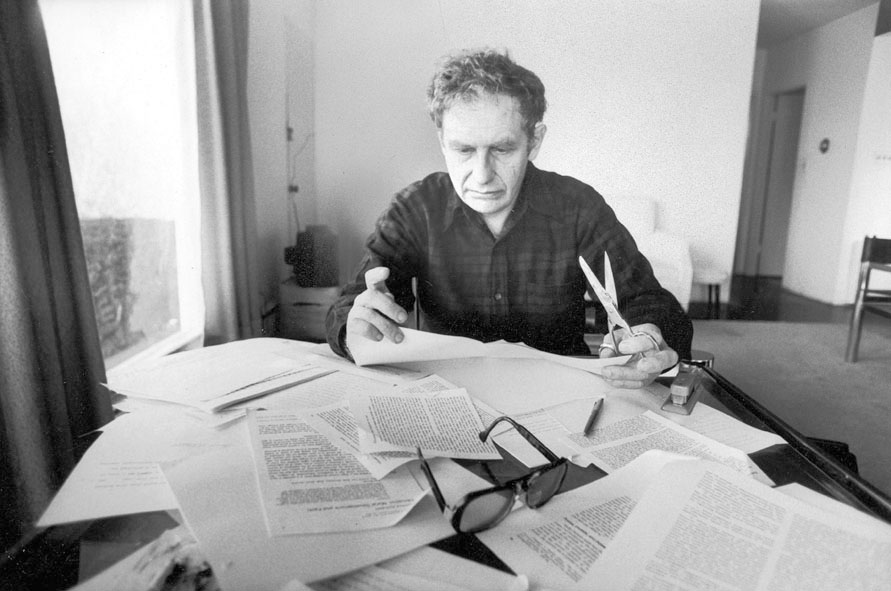

Harry Harlow used newborn monkeys in his attachment research to address this question (Harlow, 1959; Harlow & Harlow, 1962; Harlow & Zimmerman, 1959). These attachment studies were a consequence of an accidental discovery during his learning research using the infant monkeys. The infant monkeys often caught diseases from their mothers, so Harlow had separated the infant monkeys from their mothers. He gave cheesecloth blankets to the isolated infant monkeys. The infant monkeys became strongly attached to these blankets and were greatly disturbed if their “security” blankets were taken away.

After this observation, Harlow began to separate the infant monkeys from their mothers at birth and put them in cages containing two inanimate surrogate (substitute) mothers—one made of wire and one made of terry cloth. Figure 7.3 shows examples of these surrogate mothers and the motherless monkeys. Half of the monkeys received their nourishment from a milk dispenser in the wire mother and half from a dispenser in the terry cloth mother. However, all of the monkeys preferred the cloth monkey regardless of which monkey provided their nourishment. The monkeys being fed by the wire mother would only go to the wire mother to eat and then return to the cloth mother. As shown in Figure 7.3, if possible, the infant monkeys would often cling to the cloth monkey while feeding from the wire mother. In brief, the infant monkeys would spend most of each day on the cloth mother. The monkeys clearly had become attached to the cloth mother. Harlow concluded that “contact comfort” (bodily contact and comfort), not reinforcement from nourishment, was the crucial element for attachment formation.

Photo Researchers, Inc.

299

In addition, the infant monkeys would cower in fear when confronted with a strange situation (an unfamiliar room with various toys) without the surrogate mother. When the surrogate mother was brought into the strange situation, the infant monkeys would initially cling to the terry cloth mother to reduce their fear, but then begin to explore the new environment and eventually play with the toys. Harlow concluded that the presence of the surrogate mother made the monkeys feel secure and therefore sufficiently confident to explore the strange situation. This situation is very similar to the strange situation procedure developed by Mary Ainsworth to study the attachment relationship in human infants (Ainsworth, 1979; Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978). In this procedure, an infant’s behavior is observed in an unfamiliar room with toys, while the infant’s mother and a stranger (an unfamiliar woman) move in and out of the room in a structured series of situations. The key observations focus on the infant’s reaction to the mother’s leaving and returning, both when the stranger is present and absent, and on the child exploring the situation (the room and the toys in it).

300

Types of attachment.

Ainsworth and her colleagues found three types of attachment relationships—secure, insecure-avoidant, and insecure-ambivalent. Secure attachment is indicated by the infant exploring the situation freely in the presence of the mother, but displaying distress when the mother leaves, and responding enthusiastically when the mother returns. Insecure-avoidant attachment is indicated by exploration but minimal interest in the mother, the infant showing little distress when the mother leaves, and avoiding her when she returns. Insecure-ambivalent attachment is indicated by the infant seeking closeness to the mother and not exploring the situation, high levels of distress when the mother leaves, and ambivalent behavior when she returns by alternately clinging to and pushing away from her. About two-thirds of the infants studied are found to have a secure attachment, and the other third insecure attachments. Cross-cultural research indicates that these proportions may vary across different cultures, but the majority of infants worldwide seem to form secure attachments. Later researchers have added a fourth type of insecure attachment, insecure-disorganized (disoriented) attachment, which is indicated by the infant’s confusion when the mother leaves and when she returns. The infant acts disoriented, seems overwhelmed by the situation, and does not demonstrate a consistent way of coping with it (Main & Solomon, 1990).

Before putting the infants in the strange situation series, researchers observed the infant–mother relationship at home during the first six months of an infant’s life. From such observations, they found that the sensitivity of the mother is the major determinant of the quality of the attachment relationship. A mother who is sensitive and responsive to an infant’s needs is more likely to develop a secure attachment with the infant. Although the mother’s caregiver style is primary, does the infant also contribute to the attachment formation? The answer is yes. Each of us is born with a temperament, a set of innate tendencies or dispositions that lead us to behave in certain ways. Our temperament is fundamental to both our personality development and also how we interact with others (our social development). The temperaments of infants vary greatly. Some infants are more responsive, more active, and happier than others. How an infant’s temperament matches the child-rearing expectations and personality of his caregiver is important in forming the attachment relationship. A good match or fit between the two enhances the probability of a secure attachment.

301

The type of attachment that is formed is important to later development. Secure attachments in infancy have been linked to higher levels of cognitive functioning and social competence in childhood (Jacobsen & Hoffman, 1997; Schneider, Atkinson, & Tardif, 2001). This doesn’t mean, however, that the type of attachment cannot change or that an insecure attachment cannot be overcome by later experiences. As family circumstances change, interactions change and so may the type of attachment. For example, divorce might put a child into day care, or remarriage might bring another caring adult into the family. This brings us to a very important question in our present-day society of working mothers and single parents: Is day care detrimental to the formation of secure attachments and therefore to cognitive and social development? The general answer is no. Children in day care seem to be generally as well off as those who are raised at home (Erel, Oberman, & Yirmiya, 2000; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 1997, 2001). However, the effects of day care for a particular child are moderated by many variables, such as the age of the child when starting day care, the number of hours of day care per week, and the quality of the day care.

Parenting styles.

Attachment formation in infants is important in shaping later development. But how do parenting styles impact development in children and adolescents? Diana Baumrind (1971, 1991) has identified four styles of parenting—authoritarian, authoritative, permissive, and uninvolved (Baumrind, 1971, 1991). Authoritarian parents are demanding, expect unquestioned obedience, are not responsive to their children’s desires, and communicate poorly with their children. Authoritative parents are demanding but set rational limits for their children and communicate well with their children. Permissive parents make few demands and are overly responsive to their children’s desires, letting their children do pretty much as they please. Uninvolved parents minimize both the time they spend with the children and their emotional involvement with them. They provide for their children’s basic needs but little else. These parenting styles have been related to differences in cognitive and social development. Authoritative parenting seems to have the most positive effect on a child’s development (Baumrind, 1996). The children of authoritative parents are not only the most independent, happy, and self-reliant, but also the most academically successful. These relationships between parenting style and child development were primarily established based on studies of white, middle-class families. Recent studies of more diverse populations and cultures suggest that these effects may vary across different ethnic and cultural groups. For instance, an authoritarian parenting style is associated with more positive outcomes for African-American girls and children of Chinese parents. The existence of these cultural differences illustrates that development is impacted not only by the immediate family but also by the broader cultural context in which the child lives (Bronfenbrenner, 1993).

302

So far we have discussed social development for the infant and child in terms of attachment and parenting styles, but such development involves others as well, such as friends and teachers. Friends become increasingly important and assume different functions as children age (Furman & Bierman, 1984; Simpkins, Parke, Flyr, & Wild, 2006). Early friendships are primarily due to children having similar play interests or living close together. As adolescence approaches, however, friendships begin to serve more important emotional needs, and friends provide emotional support for one another. Despite the increasing importance of friends, adolescents still value their relationships with their parents and try to uphold parental standards on major issues such as careers and education. In addition to friends, children are also part of a larger social peer network in which the social status of members varies (Asher, 1983; Jiang & Cillessen, 2005). Popular children tend to be liked by most other children and have good social skills. Children who are rejected by their peers, however, lack these social skills and often tend to be either aggressive or withdrawn. Rejected children are at increased risk for both emotional and social difficulties (Buhs & Ladd, 2001).

Theory of Mind

One of the most important social developments that occurs in early childhood is in the area of social cognition—the development of a theory of mind. Theory of mind refers to the understanding of the mental and emotional states of both ourselves and others. In order to have a theory of mind, children must realize that other people do not necessarily think the same thoughts, have the same beliefs, or feel the same emotions that they themselves do. Whenever we interact with others, we interpret and explain their behavior in terms of their beliefs, desires, and emotions. If a friend is angry, we might explain it by attributing it to his or her belief that we did something to upset them. It is difficult to imagine what social relationships would be like if we were unable to infer the mental and emotional states of others.

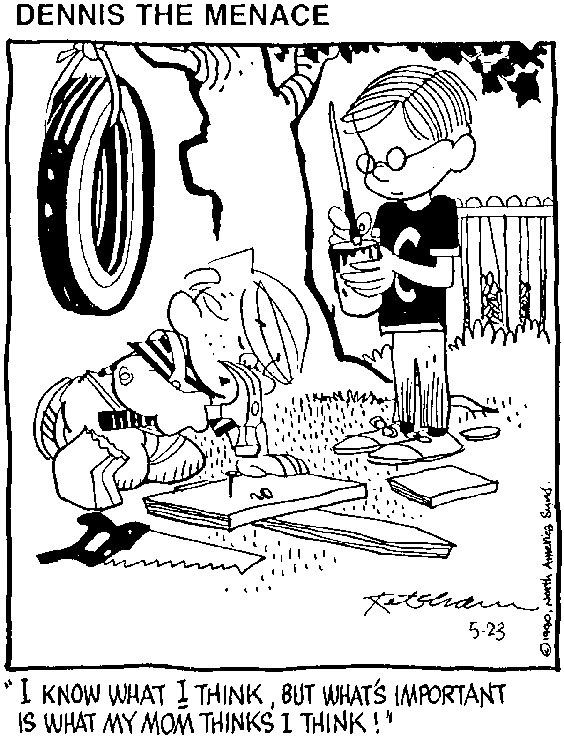

While there are many aspects of theory of mind development that begin in infancy and early childhood, one critical theory of mind accomplishment is the understanding of false beliefs (recognizing that others can have beliefs about the world that are wrong) that typically develops between four and five years of age. To test for this understanding, researchers use false-belief problems in which another person believes something to be true that the child knows is false. The question is whether the child thinks that the other person will act in accord with his false belief or with the child’s correct understanding of the situation. These problems reveal whether the child has the understanding that different people can have different beliefs about the same situation. For example, in an unexpected location task designed to assess false-belief understanding, a child sees a ball being hidden in a box by Big Bird and then Big Bird leaves the room to play outside. Next, the child observes Cookie Monster move the ball to a toy chest. The child is then asked where Big Bird will think the ball is when he comes back in from playing. A five–year-old can accurately predict that Big Bird will think it is in the original box even though the child knows it is in the toy chest. That is, the child understands that different people can have different beliefs about the same situation. A three-year old typically does not understand this and would incorrectly predict that Big Bird would think it is in the toy chest, because younger children believe that everyone thinks like they do. Such findings are extremely robust and have been observed with different problems and in different cultures (Wellman, Cross, & Watson, 2001).

303

The early emergence of theory of mind understanding has led some researchers to suggest that there is a biological basis for this knowledge (Baron-Cohen, 2000). The developmental disorder of autism, in which children are primarily characterized by difficulty in social interactions, supports this biological view of theory of mind (Frith, 2003). What might be the biological basis for theory of mind development? We have already learned about one possibility. Remember, in Chapter 4 we learned that mirror neuron systems may provide the neural basis for imitation learning and play a role in empathy and the understanding of the intentions and emotions of others. Thus, early mirror neuron system deficits might cascade into developmental impairments in imitation learning and subsequently in theory of mind development, leading to autism (Iacoboni & Dapretto, 2006; Williams, Whiten, Suddendorf, & Perrett, 2001). For example, Dapretto et al. (2006) had high-functioning children with autism and normal control children undergo fMRI while imitating emotional expressions. For the children with autism, they found little activity in brain regions associated with mirror neurons. For the children without autism, however, these regions were active, suggesting that a dysfunctional mirror-neuron system may underlie the social deficits observed in autism. We must remember, however, that this is presently just a hypothesis and that much more extensive research must be conducted before any firm conclusions can be made.

304

We have primarily focused on social development during childhood and adolescence but social development continues throughout our lives. This is why we now turn to Erik Erikson’s stage theory of how we develop throughout our life, from birth to old age.

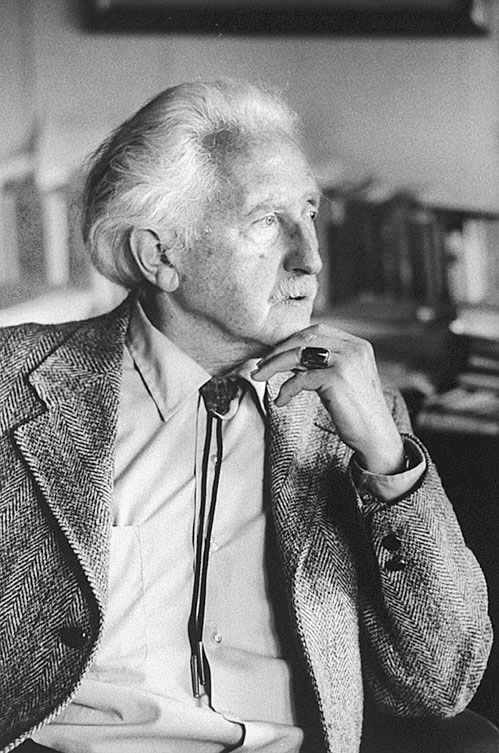

Erikson’s Psychosocial Stage Theory of Development

Erik Erikson’s psychosocial stage theory covers the whole life span. Like Vygotsky, Erikson emphasized the impact of society and culture upon development, but Erikson’s theory is different because it considered both personality development and social development. We discuss it here rather than in the next chapter, with the other personality theories, because it is a developmental theory. In fact, Erikson’s inclusion of the three stages of adulthood in his theory has played a major role in the increased amount of research on all parts of the life span—not just on childhood and adolescence. However, Erikson’s theory has been criticized because of the lack of solid experimental data to support it. Erikson used only observational data, which is a criticism that can be leveled against most personality theories.

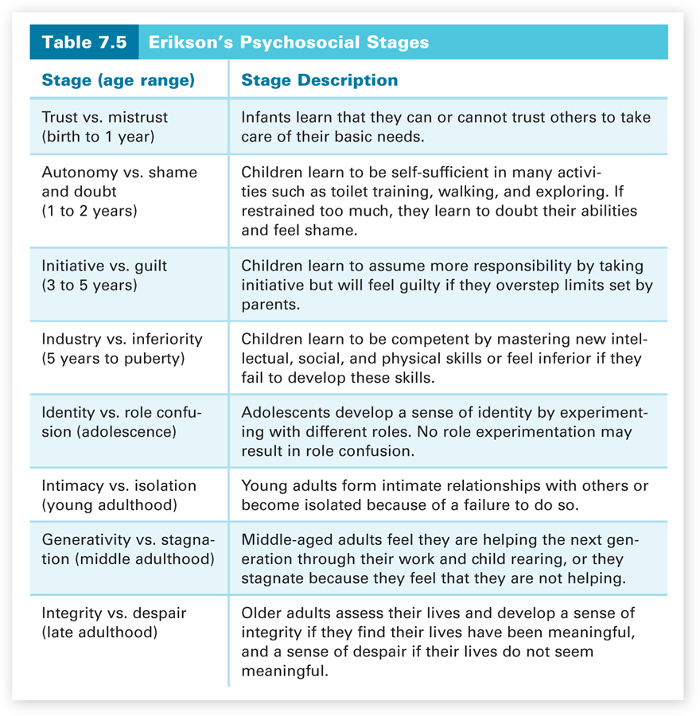

Erikson divided the life span into eight stages of development, summarized in Table 7.5 (Erikson, 1950, 1963, 1968, 1980). The first five stages cover infancy, childhood, and adolescence, where Freud’s theory of personality development (discussed in the next chapter) and Piaget’s theory of cognitive development end. Erikson’s last three stages go beyond Freud and Piaget and deal with the three stages of adulthood (young, middle, and late).

305

Erikson viewed our social-personality development as the product of our social interactions and the choices we make in life. At each stage, there is a major psychosocial issue or crisis that has to be resolved. Think of each stage as a “fork in the road” choice whose resolution greatly impacts our development. Each stage is named after the two sides of the issue relevant in that stage. For example, the first stage is trust versus mistrust. In this stage, infants in the first year of life are wrestling with the issue of whether they can trust or not trust others to take care of them. The resolution of each stage can end up on either side of the issue. The infant can leave the first stage either generally trusting or generally mistrusting the world. When an issue is successfully resolved, the person increases in social competence. Erikson felt that the resolution of each stage greatly impacted our personal development. Table 7.5 includes the possible resolutions for each stage.

306

Erikson’s best-known concept, identity crisis, is part of his fifth stage. The main task of this stage is the development of a sense of identity—to figure out who we are, what we value, and where we are headed in life. As adolescents, we are confused about our identity. The distress created by the confusion is what Erikson meant by identity crisis. For most adolescents, however, it’s more of a search or exploration than a crisis. Teenagers experiment with different identities in the search to find their own. If you are a traditional-age college student, you may have just experienced or are still experiencing this search. Attending college and searching for a major and a career path may delay the resolution of this stage. Finding our true selves is clearly not easy. We usually explore many alternative identities before finding one that is satisfactory.

This identity stage is critical to becoming a productive adult, but development doesn’t end with its resolution. Probably the greatest impact of Erikson’s theory is that it expanded the study of developmental psychology past adolescence into the stages of adulthood. In young adulthood (from the end of adolescence to the beginning of middle age), a person establishes independence from her parents and begins to function as a mature, productive adult. Having established her own identity, a person is ready to establish a shared identity with another person, leading to an intimate relationship. This sequence in Erikson’s theory (intimacy issues following identity issues) turns out to be most applicable to men and career-oriented women (Dyk & Adams, 1990). Many women may solve these issues in reverse order or simultaneously. For example, a woman may marry and have children and then confront the identity issues when her children become adults.

The crisis in middle adulthood (from about age 40 to age 60) is concerned with generativity versus stagnation. “Generativity” is being concerned with the next generation and producing something of lasting value to society. Generative activity comes in many forms. In addition to making lasting contributions to society, which most of us will not do, generative activity includes rearing children, engaging in meaningful work, mentoring younger workers, and contributing to civic organizations.

In Erikson’s final stage, late adulthood, we conduct reviews of our lives, looking back at our lives to assess how well we have lived them. If we are satisfied, we gain a sense of integrity and the ability to face death. If not, we despair and look back with a sense of sadness and regret, and we fear death.

Section Summary

The most influential theory of moral development is Kohlberg’s stage theory of moral reasoning. Using moral dilemmas, Kohlberg proposed three levels of reasoning—preconventional, conventional, and postconventional. The first level is self-oriented, and the emphasis is on avoiding punishment and looking out for one’s own needs. At the conventional level, reasoning is guided by social approval and being a dutiful citizen. At the highest postconventional level, morality is based on universal ethical principles and the realization that society’s laws are only a social contract, which can be broken if they violate these more global principles. Research indicates that proceeding through the stages is related to age and cognitive development, but that most people do not reach the postconventional stage of reasoning. The theory is criticized for being based on moral reasoning and not moral behavior (since these may be very different); for being biased against women, who may focus more on a morality of care than a morality of justice; and for being biased toward Western moral values.

307

Social development begins with attachment, the strong emotional bond formed between an infant and his mother or primary caregiver. Harry Harlow’s studies with infant monkeys and surrogate mothers found that contact comfort, and not reinforcement from nourishment, is the crucial element in attachment formation. Using Mary Ainsworth’s strange situation procedure, researchers have identified four types of attachment—secure, insecure-avoidant, insecure-ambivalent, and insecure-disorganized. The sensitivity of the caregiver to the infant and how well an infant’s temperament matches the child-rearing expectations and personality of the caregiver are important to attachment formation. The majority of infants worldwide form secure attachments, and this type of attachment has been linked to higher levels of social competence and cognitive functioning in childhood. With respect to parenting styles, authoritative parenting—in which the parents are demanding but rational in setting limits for their children and communicate well with their children—seems to have the most positive effect on social and cognitive development. Recent research, however, indicates that parenting style effects may vary across ethnic and cultural groups. Friends are also important to social development, especially during adolescence when friendships serve important emotional needs.

One of the most important social developments that occurs in early childhood is the development of a theory of mind, the understanding of the mental and emotional states of both ourselves and others. One critical accomplishment in theory of mind development is the understanding of false beliefs around four to five years of age. To test for this understanding, researchers use false-belief problems in which another person believes something to be true that the child knows is false. If the child has the understanding of false beliefs, he will predict that the other person will act in accord with his false belief and not the child’s correct understanding of the situation. Children without an understanding of false beliefs would make just the opposite prediction. The early emergence of theory of mind development has led some researchers to suggest that there is a biological basis for it. Mirror neuron systems are a possibility for this basis because they seem to provide the neural basis for imitation learning and play a role in empathy and the understanding of the intentions and emotions of others. Thus, early mirror neuron system deficits might lead to developmental impairments in imitation learning and subsequently theory of mind development, leading to social disorders such as autism.

With respect to social development across the life span, Erik Erikson developed an eight-stage theory of social and personality development. In each stage, there is a major psychosocial issue with two sides that has to be resolved. If the stage is resolved successfully, the person leaves the stage on the positive side of the stage issue. For example, the infant in the first year of life is dealing with the issue of trust versus mistrust. If resolved successfully, the infant will leave this stage trusting the world. Erikson stressed the fifth stage, in which a sense of identity must be developed during adolescence. This is the stage during which the identity crisis occurs. Erikson’s theory is unusual in that it includes the three stages of adulthood. This inclusion played a major role in leading developmental psychologists to expand their focus to development across the entire life span.

308

ConceptCheck | 3

Describe how Kohlberg would classify the following response explaining why Heinz should not steal the drug. “You shouldn’t steal the drug because you’ll be caught and sent to jail if you do. If you do get away with it, your conscience would bother you thinking how the police would catch up with you any minute.”

Describe how Kohlberg would classify the following response explaining why Heinz should not steal the drug. “You shouldn’t steal the drug because you’ll be caught and sent to jail if you do. If you do get away with it, your conscience would bother you thinking how the police would catch up with you any minute.”The response indicates that Heinz should not steal the drug because he would be caught and sent to jail—punished. Even if he weren’t caught, his conscience would punish him. Thus, Kohlberg would classify this explanation for not stealing the drug as reflective of Stage 1 (punishment orientation) in which people comply with rules in order to avoid punishment.

Explain why an infant’s temperament is important to the process of attachment formation.

Explain why an infant’s temperament is important to the process of attachment formation.An infant’s temperament is the set of innate dispositions that lead him to behave in a certain way. It determines the infant’s responsiveness in interactions with caregivers, how happy he is, how much he cries, and so on. The temperaments of infants vary greatly. Those that fit the child-rearing expectations and personality of the caregivers likely facilitate attachment formation. Difficult infants probably do not.

Explain the differences between authoritarian and authoritative parenting styles.

Explain the differences between authoritarian and authoritative parenting styles.Authoritarian parents are demanding and expect unquestioned obedience, are not responsive to their children’s desires, and do not communicate well with their children. Authoritative parents, however, are demanding but reasonably so. Rather than demanding blind obedience, they explain the reasoning behind rules. Unlike authoritarian parents, they are both responsive to and communicate well with their children.

In the false-belief problem described in the text involving Big Bird and Cookie Monster, how will a child who does not have an understanding of false beliefs answer, and why will he answer in this way? How will he answer if he has an understanding of false beliefs, and why will he answer in this way?

In the false-belief problem described in the text involving Big Bird and Cookie Monster, how will a child who does not have an understanding of false beliefs answer, and why will he answer in this way? How will he answer if he has an understanding of false beliefs, and why will he answer in this way?A child without understanding of false beliefs would predict that Big Bird will look for the ball in the toy chest where Cookie Monster has rehidden it, because the child does not understand that others can have beliefs that disagree with his. If the child has an understanding of false beliefs, he would predict that Big Bird will look in the box where he had earlier put the ball because he realizes that others can have beliefs that disagree with his.

Explain what Erikson meant by psychosocial issue or crisis.

Explain what Erikson meant by psychosocial issue or crisis.Erikson thought that at each stage there is a major psychosocial issue or crisis (e.g., identity versus role confusion) that has to be resolved and whose resolution greatly impacts one’s development. For each crisis, there is a positive adaptive resolution and a negative maladaptive resolution. When an issue is positively resolved, social competence increases and one is more adequately prepared for the next issue.

309