How We Think About Our Own and Others' Behavior

Social thinking is concerned with how we view our own attitudes and behavior and those of others. We will discuss two of the major areas of research on social thinking—attributions and attitudes. First, we will examine attribution, the process (briefly discussed in Chapter 8) by which we explain our own behavior and the behavior of others. In other words, what do we perceive to be the causes of our behavior and that of others? Is the behavior due to internal causes (the person) or external causes (the situation)? Remember, we show a self-serving bias when it comes to explaining our own behavior. In this section, we will revisit this bias and examine two other biases in the attribution process (the fundamental attribution error and the actor-observer bias). The second major topic to be discussed is the relationship between our attitudes and our behavior. For example, do our attitudes drive our behavior, does our behavior determine our attitudes, or is it some of both? We will also consider the impact of role-playing on our attitudes and behavior.

379

How We Make Attributions

Imagine it’s the first cold day in the fall, and you’re standing in a long line for coffee at the student union coffee shop. All of a sudden, a person at the head of the line drops her cup of coffee. You turn to your friend and say “What a klutz!” inferring that this behavior is characteristic of that person. You are making an internal (dispositional) attribution, attributing the cause of dropping the cup of coffee to the person. But what if it had been you who had dropped the cup of coffee? Chances are you would have said something like, “Boy was that cup hot!” making an external (situational) attribution by inferring that dropping the cup wasn’t your fault. We have different biases in the attributions we make for behavior we observe versus our own behavior. Let’s look first at being an observer.

Attributions for the behavior of others.

As an observer, we tend to commit the fundamental attribution error (Ross, 1977). The fundamental attribution error is the tendency as an observer to overestimate internal dispositional influences and underestimate external situational influences on others’ behavior. Simply put, observers are biased in that they tend to attribute others’ behavior to them and not the situation they are in. In the coffee example, we tend to make an internal attribution (the person is a klutz) and ignore possible external situational factors, such as the cup being really hot or slippery. The fundamental attribution error tends to show up even in experiments in which the participants are told that people are only faking a particular type of behavior. For example, in one experiment participants were told that a person was only pretending to be friendly or to be unfriendly (Napolitan & Goethals, 1979). Even with this knowledge, participants still inferred that the people were actually like the way they acted, either friendly or unfriendly.

Think about the participants in Milgram’s obedience experiments. On first learning of their destructive obedient behavior, didn’t you think the teachers were horrible human beings? How could they treat fellow humans in that way? Or consider the teachers themselves in these experiments. When the learners kept making mistakes, the teachers may have thought the learners were incredibly stupid and so deserved the shocks. People who have been raped are sometimes blamed for provoking the rape, and people who are homeless are often blamed for their poverty-stricken state. Placing blame in this manner involves the just-world hypothesis, the assumption that the world is just and that people get what they deserve (Lerner, 1980). Beware of just-world reasoning. It is not valid, but is often used to justify cruelty to others.

The fundamental attribution error impacts our impressions of other people. There are two related concepts that you should also be aware of when forming impressions of others—the primacy effect and the self-fulfilling prophecy. In the primacy effect, early information is weighted more heavily than later information in forming an impression of another person. Beware of this effect when meeting someone new. Develop your impression slowly and carefully by gathering more information across time and from many different situations. Also be careful about the initial impressions that you make on people. Given the power of the primacy effect, your later behavior may not be able to change their initial impression of you. Try to be your true self when you first meet someone so that the primacy effect will be more accurate.

380

In the self-fulfilling prophecy, our expectations of a person elicit behavior from that person that confirms our expectations. In other words, our behavior encourages the person to act in accordance with our expectations (Jones, 1977; Rosenthal & Jacobson, 1968). For example, if you think someone is uncooperative, you may act hostile and not be very cooperative in your interactions with that person. Given your hostile behavior, the person responds by being uncooperative, confirming your expectations. The person may not really be uncooperative, however, and may only act this way in response to your behavior. However, your expectations will have been confirmed, and you will think that the person is uncooperative. Self-fulfilling prophecy is related to our tendency toward confirmation bias in hypothesis testing (see Chapter 6). Rather than acting in a manner that confirms your expectations, act in the opposite way (in the example, instead of being uncooperative, be cooperative) and see what happens. You may be surprised.

Attributions for our own behavior.

Now let’s consider our own behavior and making attributions. Our attribution process is biased in a different way when we are actors and not observers. Think about the example where you dropped the cup of coffee (you were the actor). You don’t make a dispositional attribution (“I’m clumsy”). You make a situational attribution (“The cup was slippery”). As actors we tend to have what’s called the actor-observer bias, the tendency to attribute our own behavior to situational influences, but to attribute the behavior of others to dispositional influences. Why this difference in attributional bias? As observers, our attention is focused on the person, so we see him as the cause of the action. As actors, our attention is focused on the situation, so we see the situation as the cause of the action. We are more aware of situational factors as actors than as observers. This explanation is supported by the fact that we are less susceptible to the bias toward dispositional attributions with our friends and relatives, people whom we know well.

We described another attribution bias in the last chapter, the self-serving bias—the tendency to make attributions so that one can perceive oneself favorably. As actors, we tend to overestimate dispositional influences when the outcome of our behavior is positive and to overestimate situational influences when the outcome of our behavior is negative. In the last chapter, we were discussing this bias’s role as a defense mechanism against depression. In this chapter, let’s look at how self-serving bias qualifies the actor-observer bias. It defines the type of attribution we make as actors based on the nature of the outcome of our actions. Think about our reaction to a test grade. If we do well, we think that we studied hard and knew the material, both dispositional factors. If we don’t do well, then we may blame the test and the teacher (“What a tricky exam,” Or “That test was not a good indicator of what I know”). We take credit for our successes but not our failures. Teachers also have this bias. For example, if the class does poorly on a test, the teacher thinks that the test she made up was just fine, but that the students weren’t motivated or didn’t study. It is important to realize that the self-serving bias and the other attribution biases do not speak to the correctness of the attributions we make, but only to the types of attributions we tend to make. This means that our attributions will sometimes be correct and sometimes incorrect.

381

The self-serving bias also leads us to see ourselves as “above average” when we compare ourselves to others on positive dimensions, such as intelligence and attractiveness. This tendency is exemplified in Garrison Keillor’s fictional Lake Wobegon community, where, “All the women are strong, all the men are good-looking, and all the children are above average.” We tend to rate ourselves unreasonably high on dimensions that we value (Mezulis, Abramson, Hyde, & Hankin, 2004). Think about it. If you were asked to compare yourself to other people on intelligence, what would you say? If you respond like most people, you would say “above average.” However, most people cannot be “above average.” Many of us have to be average or below average. Intelligence, like most human traits, is normally distributed with half of us below average and half of us above average.

The self-serving bias also influences our estimates of the extent to which other people think and act as we do. This leads to two effects—the false consensus effect and the false uniqueness effect (Myers, 2013). The false consensus effect is the tendency to overestimate the commonality of one’s opinions and unsuccessful behaviors. Let’s consider two examples. If you like classical music, you tend to overestimate the number of people who also like classical music, or if you fail all of your midterm exams, you tend to overestimate the number of students who also failed all of their midterms. You tend to think that your opinion and your negative behavior are the consensus opinion and behavior.

The false uniqueness effect is the tendency to underestimate the commonality of one’s abilities and successful behaviors. For example, if you are a good pool player, you tend to think that few other people are. Or, if you just aced your psychology exam, you think few students did so. You think your abilities and successful behaviors are unique. The false consensus effect and the false uniqueness effect relate to the self-protective function of the self-serving bias. We want to protect and enhance our view of ourselves, our self-esteem.

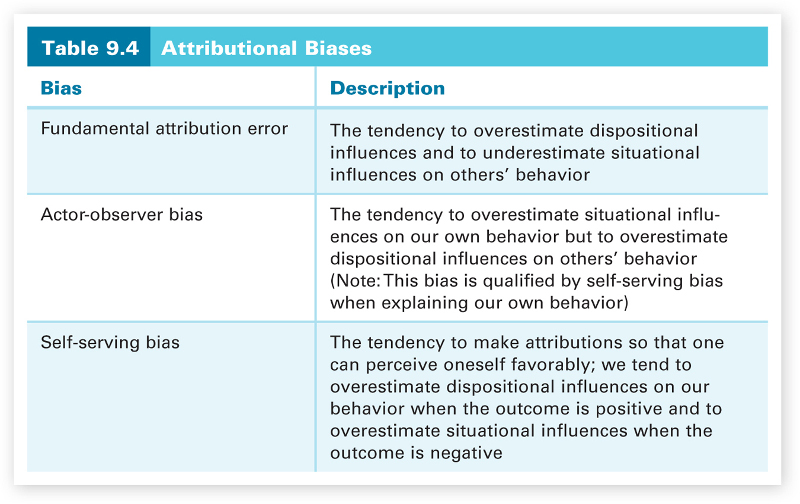

All three major attributional biases (the fundamental attribution error, the actor-observer bias, and the self-serving bias) are summarized in Table 9.4.

382

How Our Behavior Affects Our Attitudes

In this section, we are going to consider our attitudes. In simple terms, attitudes are evaluative reactions (positive or negative) toward things, events, and other people. Our attitudes are our beliefs and opinions. What do you think of the Republican political party, abortion, President Barack Obama, Twitter, or rap music? Have you changed any of your attitudes during your life, especially since you have been in college? Most of us do. Our attitudes often determine our behavior, but this is not always the case.

When our behavior contradicts our attitudes.

Our attitudes tend to guide our behavior when the attitudes are ones that we feel strongly about, when we are consciously aware of our attitudes, and when outside influences on our behavior are not strong. For example, you may think that studying is the top priority for a student. If you do, you will likely get your studying done before engaging in other activities. However, if there is a lot of pressure from your roommates and friends to stop studying and go out partying, you may abandon studying for partying. But what happens when our attitudes don’t guide our behavior and there isn’t a lot of outside influence on our behavior? To help you understand the answer to this question, we’ll consider a classic study (Festinger & Carlsmith, 1959).

Imagine that you are a participant in an experiment. You show up at the laboratory at the assigned time, and the experiment turns out to be incredibly boring. For an hour, you perform various boring tasks, such as turning pegs on a pegboard over and over again or organizing spools in a box, dumping them out, and then organizing them again. When the hour is over, the experimenter explains to you that the experiment is concerned with the effects of a person’s expectations on their task performance and that you were in the control group. The experimenter is upset because his student assistant hasn’t shown up. She was supposed to pose as a student who has just participated in the experiment and tell the next participant who is waiting outside that this experiment was really enjoyable. The experimenter asks if you can help him out by doing this, and for doing so, he can pay you. His budget is small, though, so he can only pay you $1. Regardless, you agree to help him out and go outside and tell the waiting participant (who is really a confederate of the experimenter and not a true participant) how enjoyable and interesting the experiment was.

383

Before you leave, another person who is studying students’ reactions to experiments asks you to complete a questionnaire about how much you enjoyed the earlier experimental tasks. How would you rate these earlier incredibly boring tasks? You are probably thinking that you would rate them as very boring, because they were. However, this isn’t what researchers observed. Participants’ behavior (rating the tasks) did not follow their attitude (the tasks were boring). Participants who were paid only $1 for helping out the experimenter (by lying about the nature of the experimental tasks to the next supposed participant) rated the tasks as fairly enjoyable. We need to compare this finding with the results for another group of participants who received $20 for lying about the experiment. Their behavior did follow their attitude about the tasks. They rated the tasks as boring. This is what researchers also found for another group of participants who were never asked to help out the experimenter and lie. They also rated the tasks as boring. So why did the participants who lied for $1 not rate the tasks as boring?

Before answering this question, let’s consider another part of this experiment. After rating the task, participants met again with the experimenter to be debriefed, and were told the true nature of the study. Following the debriefing, the experimenter asks you to give back the money he paid you. What would you do if you were in the $20 group? You are probably saying, “No way,” but remember the studies on obedience and the high rates of obedience that were observed. What actually happened? Just like all of the participants agreed to lie (whether for $1 or $20), all of the participants gave back the money, showing once again our tendency to be obedient and comply with requests of those in authority. Now let’s think about why the $1 group rated the tasks differently than the $20 group.

Festinger’s cognitive dissonance theory.

Their behavior can be explained by Leon Festinger’s cognitive dissonance theory, which proposes that people change their attitudes to reduce the cognitive discomfort created by inconsistencies between their attitudes and their behavior (Festinger, 1957). Let’s consider a real-life example before applying this theory to the participants who were paid $1 for lying. Think about people who smoke. Most smokers have the attitude (believe) that smoking is dangerous to their health, but they continue to smoke. Cognitive dissonance theory says that smokers feel cognitive discomfort because of the inconsistency between their attitude about smoking (dangerous to their health) and their behavior (continuing to smoke). To reduce this cognitive disharmony, either the attitude or the behavior has to change. According to the cognitive dissonance theory, many smokers change their attitude so that it is no longer inconsistent with their behavior. For example, a smoker may now believe that the medical evidence isn’t really conclusive. The change in the attitude eliminates the inconsistency and the dissonance it created. So now let’s apply cognitive dissonance theory to the participants in the boring task study who lied for $1. Why did they rate the task as enjoyable? Their attitude was that the tasks were incredibly boring, but this was inconsistent with their behavior, lying about the tasks for only $1. This inconsistency would cause them to have cognitive dissonance. To reduce this dissonance, the participants changed their attitude to be that the tasks were fairly enjoyable. Now the inconsistency and resulting dissonance are gone.

384

A key aspect of cognitive dissonance theory is that we don’t suffer dissonance if we have sufficient justification for our behavior (the participants who were paid $20 in the study) or our behavior is coerced. Also, cognitive dissonance sometimes changes the strength of an attitude so that it is consistent with past behavior. Think about important decisions that you have made in the past, for example, which college to attend. Cognitive dissonance theory says that once you make such a tough decision, you will strengthen your commitment to that choice in order to reduce cognitive dissonance. Indeed, the attractiveness of the alternate choices fades with the dissonance (you don’t understand why you ever were attracted to the other schools) as you find confirming evidence of the correctness of your choice (you like your classes and teachers) and ignore evidence to the contrary (such as your school not being as highly rated as the other schools). Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson (2007) provide numerous real-world examples of this cognitive dissonance–driven justification of our decisions, beliefs, and actions in their illuminating book, Mistakes Were Made (But Not By Me). Recent research by Egan, Santos, and Bloom (2007) indicates that such decision rationalization even appears in children and nonhuman primates (Egan, Santos, & Bloom, 2007).

Bem’s self-perception theory.

There have been hundreds of studies on cognitive dissonance, but there is an alternative theoretical explanation for the results of some of these studies—Daryl Bem’s self-perception theory, which proposes that when we are unsure of our attitudes we infer them by examining our behavior and the context in which it occurs (Bem, 1972). According to Bem, we are not trying to reduce cognitive dissonance, but are merely engaged in the normal attribution process that we discussed earlier in this chapter. We are making self-attributions. Self-perception theory would say that the participants who lied for $1 in the boring tasks experiment were unsure of their attitudes toward the tasks. They would examine their behavior (lying for $1) and infer that the tasks must have been fairly enjoyable and interesting or else they would not have said that they were for only $1. Those paid $20 for lying would not be unsure about their attitude toward the boring tasks, because they were paid so much to lie about them. According to self-perception theory, people don’t change their attitude because of their behavior but rather use their behavior to infer their attitude. People are motivated to explain their behavior, not to reduce dissonance. According to self-perception theory, there is no dissonance to be reduced.

385

So which theory is better? Neither is really a better theory than the other. Both theories have merit and both seem to operate—but in different situations. This is similar to our earlier discussion of color vision theories, the trichromatic-color theory and the opponent-process theory in Chapter 3. Remember that trichromatic-color theory operates at the receptor cell level and opponent-process theory at the post-receptor cell level in the visual pathways. Cognitive dissonance theory seems to be the best explanation for behavior that contradicts well-defined attitudes. Such behavior creates mental discomfort, and we change our attitudes to reduce it. Self-perception theory explains situations in which our attitudes are not well-defined; we infer our attitudes from our behavior. As with the color vision theories, both cognitive dissonance theory and self-perception theory operate, but at different times.

The impact of role-playing.

Now let’s consider one final factor that impacts the complex relationship between our attitudes and our behavior—role-playing. We all have various social roles that we play—student, teacher, friend, son or daughter, parent, employee, and so on. Each role is defined by a socially expected pattern of behavior, and these definitions have an impact on both our behavior and our attitudes. Given the power of roles on behavior, think about how each of the various roles you play each day impacts your own attitudes and behavior. They are powerful influences. As social psychologist David Myers has observed, “we are likely not only to think ourselves into a way of acting but also to act ourselves into a way of thinking” (Myers, 2002, p. 136).

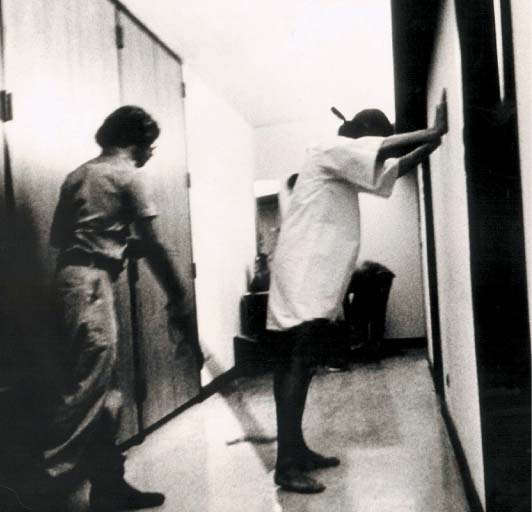

The Stanford Prison Experiment (SPE) conducted in the early 1970s at Stanford University by Philip Zimbardo has been viewed as a dramatic example of this power of roles (Haney, Banks, & Zimbardo, 1973; Zimbardo, 2007; Zimbardo, Maslach, & Haney, 1999). Zimbardo recruited male college students to participate in the study and renovated the basement in the Stanford psychology building to be a mock prison. Any volunteers with prior arrests or any with medical or mental problems were eliminated. Following psychological assessments and in-depth interviews, 24 volunteers were chosen and then randomly assigned to the roles of prisoner and guard. The guards were given uniforms and billy clubs and instructed to enforce the rules of the mock prison. The prisoners were locked in cells and had to wear humiliating clothing (smocks with no undergarments). Such clothing was used in an attempt to simulate the emasculating feeling of being a prisoner. How did the roles of prisoner and prison guard impact the attitudes and behavior of the participants?

Some of the participants began to take their respective roles too seriously. After only one day of role-playing, some of the guards started treating the prisoners cruelly. Some of the prisoners rebelled, and others began to break down. What was only supposed to be role-playing became reality. The guards’ treatment of the prisoners became both harsh and degrading. For example, some prisoners were made to clean out toilets with their bare hands. Some prisoners began to hate the guards, and some of them were on the verge of emotional collapse. The situation worsened to such a degree that Zimbardo had to stop the study after six days. According to Zimbardo and his colleagues, due to the power of their situational roles, the participating college students had truly “become” guards and prisoners. The roles transformed their attitudes and behavior. In sum, the abusive guards were not “bad apples.” It was the “bad barrel” of the Stanford prison (the situation) that temporarily transformed them.

386

It is worth noting that in 1973, the American Psychological Association published its comprehensive “Ethical Principles in the Conduct of Research with Human Participants” and in 1975, the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare issued a regulation requiring that all research with human subjects be reviewed by an institutional review board to screen prospective projects to ensure the well-being of subjects (Blass, 2004). Given the ethical storms created by Zimbardo’s SPE and Milgram’s earlier obedience experiments, both very likely played prominent roles in the development of these documents. It is also worth noting that these two renowned social psychologists who conducted such controversial research were high school classmates at James Monroe High School in the Bronx in the late 1940s. It is highly unlikely that anyone back then could have predicted that Zimbardo and Milgram would become two of the most famous psychologists of the twentieth century.

The SPE was conducted over 40 years ago, but new interest in this study was generated by the recent abuse of prisoners at Abu Ghraib, the U.S. military prison in Iraq. Like Zimbardo’s college-student guards, the American soldiers serving as prison guards engaged in dehumanizing and sadistic acts toward the prisoners. Zimbardo actually served as an expert witness in the trial of one of these soldiers and argued that situational pressures led the soldier to commit the abusive acts. His argument, however, failed, and the soldier was sentenced to a military prison. In his book, The Lucifer Effect (2007), Zimbardo details the SPE, applies the findings to the behavior of the Abu Ghraib guards and some other recent incidents, and describes a 10-step program to build up our resilience to combat pressures that lead us to act abusively toward others. The Web site www.prisonexp.org also provides detailed coverage of the SPE and links to other recent writings by Zimbardo on the Abu Ghraib prison abuses.

387

Recently, however, much criticism of Zimbardo’s situationist explanation of the SPE has surfaced (e.g., Banyard, 2007; Haslam & Reicher, 2012; Reicher & Haslam, 2006) and cast doubt on the conclusions that have been drawn from the SPE. In addition, a new prison study, the BBC Prison Study, has been conducted (Haslam & Reicher, 2005; Reicher & Haslam, 2006), and results different from those of the SPE were found. We will consider some of the criticisms, and then we will briefly describe the BBC Prison Study and its results.

First, it is not clear whether the SPE participants behaved in ways consistent with their roles because of their natural acceptance of situational role requirements as Zimbardo claims or because of the active leadership provided by Zimbardo (e.g., Banyard, 2007; Haslam & Reicher, 2012). Zimbardo served as prison superintendent and gave the guards an orientation that seems, in retrospect, to provide clear guidance about how they should behave. Zimbardo (2007) recounted the following from this orientation:

We can create boredom. We can create a sense of frustration. We can create fear in them, to some degree. We can create a notion of the arbitrariness that governs their lives, which are totally controlled by us, by the system, by you, me…. They’ll have no privacy at all, there will be constant surveillance—nothing they do will go unobserved. They will have no freedom of action. They will be able to do nothing and say nothing that we don’t permit. We’re going to take away their individuality in various ways…. In general, what all this should create in them is a sense of powerlessness. We have total power in the situation. They have none. (p. 55)

As Banyard (2007) points out, notice the use of pronouns in this orientation. Zimbardo puts himself with the guards (“we”) and gives clear instructions for the hostile environment that “we” are going to create for “them.” Thus, Zimbardo’s leadership may have legitimized oppression in the SPE. Banyard concludes that, “It is not, as Zimbardo suggests, the guards who wrote their own scripts on the blank canvas of the SPE, but Zimbardo who creates the script of terror….” (2007, p. 494). That Zimbardo’s guidance may have been critical to the SPE outcome is supported by some findings for simulated prison environments in a study conducted in Australia by Lovibond, Mithiran, and Adams (1979). These researchers found that changes in the experimental prison regime produced dramatic changes in the relations between guards and prisoners. In a more liberal prison condition in which security was maintained in a manner that allowed prisoners to retain their self-respect and in a participatory condition in which prisoners were treated as individuals and included in the decision-making process, the behavior of the guards and prisoners was rather benign and very dissimilar from the dramatic behavioral outcomes observed in the SPE.

388

Furthermore, what is surprising when you compare Zimbardo’s orientation and guidance to the findings of the SPE is that only a few of the guards were “bad” guards (Zimbardo, 2007). However, the “strict but fair” guards and the “good” guards (those that sided with the prisoners) were complicit participants, in that they did not challenge the abusive actions of the “bad” guards (those who harassed and humiliated the prisoners). The fact that only a few of the guards were “bad” guards is at odds with a pure situationist explanation of the SPE and indicates that an explanation involving the interaction of situational factors with dispositional factors, such as personality, attitudes, and expectations, is necessary. Given that only some of the guards were abusive, is it possible that there could have been some “bad apples” in the SPE? Carnahan and McFarland’s (2007) findings suggest that this is a distinct possibility. They recruited students in two ways: 1) for a psychological study of prison life using a virtually identical newspaper advertisement as used in the SPE, and 2) for just a psychological study, an identical ad but without the mention of prison life. Carnahan and McFarland found that those who volunteered to participate in the prison life study tended to be more aggressive, authoritarian, socially dominant, and Machiavellian and less empathetic and altruistic than those who volunteered for the more innocuous experiment.

In a related fashion, Banuazizi and Movahedi (1975) provided data that indicate that the SPE may have been confounded by demand characteristics (Orne, 1962). Demand characteristics are cues in the experimental environment that make participants aware of what the experimenters expect to find (their hypothesis) and how participants are expected to act. Demand characteristics can impact the outcome of an experiment, because participants may alter their behavior to conform to the experimenter’s expectations. Banuazizi and Movahedi mailed students a questionnaire that included a brief description of the procedures followed in the SPE and some open-ended questions to determine their awareness of the experimental hypothesis and their expectancies regarding the outcomes of the experiment. Of the 150 students responding, a vast majority determined the experiment’s hypothesis (81 percent) and predicted that the behavior of the guards toward prisoners would be oppressive, hostile, etc. (89.9 percent). Collectively, these results and the other various findings that we have discussed would seem to indicate that a simple situationist account of the SPE is probably just that, too simple.

Two British social psychologists, Alexander Haslam and Stephen Reicher, in collaboration with the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) re-created the SPE, but with ethical procedures that ensured that the study would not harm participants (Haslam & Reicher, 2005, Haslam & Reicher, 2012; Reicher & Haslam, 2006). This study has become known as the BBC Prison Study. It was filmed by the BBC and televised in 2002. As in the SPE, the male volunteer participants were randomly assigned to the roles of guards and prisoners within a custom-built prison setting. However, unlike Zimbardo and his colleagues, Haslam and Reicher did not assume roles within the prison and were less prescriptive about how the guards should act. What happened? Contrary to what happened in the SPE, the guards failed to identify with their role and were reluctant to impose their authority. The prisoners, however, did form a cohesive group identity, leading them to rebel and overthrow the established regime after six days. Hence, rather than brutal guards and passive prisoners, ambivalent guards and rebellious prisoners materialized. The guards and the prisoners then formed a single self-governing, egalitarian commune, but the commune fell apart after a short time, because again some participants did not want to discipline those who broke the commune’s rules. Following the collapse of the communal system, some former prisoners and former guards proposed a coup in which they would become the new guards, creating a more hard-line prisoner–guard divide and using force, if necessary, to maintain it. At this point, Haslam and Reicher brought the study to a close on the eighth day. Haslam and Reicher interpreted their findings in terms of social identity theory, in that power resides in the ability of a group to establish a sense of shared identity. This group power can be used for a positive purpose, as illustrated by the prisoners in the BBC prison study, or for a negative one, as illustrated by the guards in the SPE. They concluded that people do not automatically assume roles that are given to them, as was suggested by the situationist account of the SPE, and that it is powerlessness and the failure of groups to form identities that may lead to tyranny. As with the SPE, there is far more to the BBC prison study than can be discussed here. More information can be found in the articles cited here and at the BBC prison study Web site, www.bbcprisonstudy.org.

389

Section Summary

In this section, we considered social thinking by examining how we make attributions, explanations for our own behavior and the behavior of others, and the relationship between our attitudes and our behavior. Attribution is a biased process. As observers, we commit the fundamental attribution error, tending to overestimate dispositional influences and underestimate situational influences upon others’ behavior. This error seems to stem from our attention being focused on the person, so we see her as the cause of the action. When we view our own behavior, however, we fall prey to the actor-observer bias, the tendency to attribute our own behavior to situational influences, and not dispositional influences, as we do when we observe the behavior of others. The actor-observer bias stems from focusing our attention, as actors, on the situation and not on ourselves.

390

The actor-observer bias, however, is qualified by the self-serving bias, the tendency to make attributions so that we can perceive ourselves favorably and protect our self-esteem. As actors, we tend to overestimate dispositional influences when the outcome of our behavior is positive and to overestimate situational influences when the outcome is negative. Self-serving bias also leads us to rate ourselves as “above average” in comparison to others on positive dimensions, such as intelligence and attractiveness. It also leads to two other effects—the false consensus effect (overestimating the commonality of one’s attitudes and unsuccessful behaviors) and the false uniqueness effect (underestimating the commonality of one’s abilities and successful behaviors).

Attitudes are our evaluative reactions (positive or negative) toward objects, events, and other people. They are most likely to guide our behavior when we feel strongly about them, are consciously aware of them, and when outside influences on our behavior are minimized. Sometimes, however, our behavior contradicts our attitudes, and this situation often leads to attitudinal change. A major explanation for such attitudinal change is cognitive dissonance theory—we change our attitude to reduce the cognitive dissonance created by the inconsistency between the attitude and the behavior. Such change doesn’t occur if we have sufficient justification for our behavior, however. A competing theory, self-perception theory, argues that dissonance is not involved. Self-perception theory proposes that we are just unsure about our attitude, so we infer it from our behavior. We are merely making self-attributions. Both theories seem to operate but in different situations. For well-defined attitudes, cognitive dissonance theory seems to be the better explanation; for weakly defined attitudes, self-perception theory is the better explanation.

Both our attitudes and our behavior also seem to be greatly affected by the roles we play. These roles are defined, and the definitions greatly influence our actions and our attitudes. The impact of the roles of guard and prisoner on the behavior and attitudes of male college students was dramatically demonstrated in Zimbardo’s SPE. However, criticism of Zimbardo’s situationist explanation for these findings has recently surfaced, leading to a new prison study—Haslam and Reicher’s BBC Prison Study. This criticism and the results of the BBC Prison Study suggest that both situational and dispositional factors are necessary to explain the results of the SPE and that it is the failure of groups to form identities that may lead to tyranny.

ConceptCheck | 2

Explain how the actor-observer bias qualifies the fundamental attribution error and how self-serving bias qualifies the actor-observer bias.

Explain how the actor-observer bias qualifies the fundamental attribution error and how self-serving bias qualifies the actor-observer bias.The actor-observer bias qualifies the fundamental attribution error because it says that the type of attribution we tend to make depends upon whether we are actors making attributions about our own behavior or observers making attributions about others’ behavior. The actor-observer bias leads us as actors to make situational attributions; the fundamental attribution error leads us, as observers, to make dispositional attributions. The actor-observer bias is qualified, however, by the self-serving bias, which says that the type of attribution we make for our own actions depends upon whether the outcome is positive or negative. If positive, we tend to make dispositional attributions; if negative, we tend to make situational attributions.

Explain the difference between the false consensus effect and the false uniqueness effect.

Explain the difference between the false consensus effect and the false uniqueness effect.The false consensus effect pertains to situations in which we tend to overestimate the commonality of our opinions and unsuccessful behaviors. The false uniqueness effect pertains to situations in which we tend to underestimate the commonality of our abilities and successful behaviors. According to these effects, we think others share our opinions and unsuccessful behaviors but do not share our abilities and successful behaviors. These effects both stem from the self-serving bias, which helps to protect our self-esteem.

Explain when cognitive dissonance theory is a better explanation of the relationship between our behavior and our attitudes and when self-perception theory is a better explanation of this relationship.

Explain when cognitive dissonance theory is a better explanation of the relationship between our behavior and our attitudes and when self-perception theory is a better explanation of this relationship.Cognitive dissonance theory seems to be the better explanation for situations in which our attitudes are well-defined. With well-defined attitudes, our contradictory behavior creates dissonance; therefore, we tend to change our attitude to make it fit with our behavior. Self-perception theory seems to be the better explanation for situations in which our attitudes are weakly defined. We make self-attributions using our behavior to infer our attitudes.

391