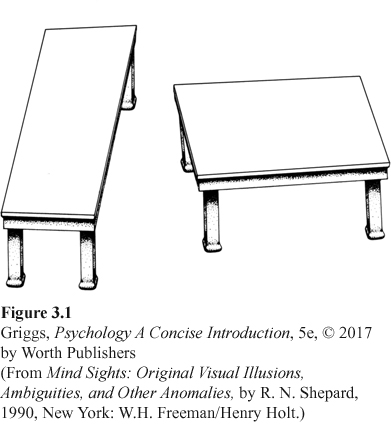

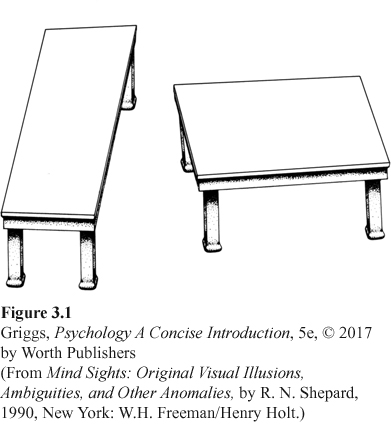

Figure 3.1: Figure 3.1 | Turning the Tables, an Example of a Misperception | The two tabletops appear to have different dimensions and shapes. Surprisingly, however, they are identical. To convince yourself, measure one and then compare it to the other. Even knowing this, you cannot make your brain see them as identical.

(From Mind Sights: Original Visual Illusions, Ambiguities, and Other Anomalies, by R. N. Shepard, 1990, New York: W.H. Freeman/Henry Holt.)

Imagine what you would be like if you couldn’t see, hear, taste, smell, or feel. You could be described as alive only in the narrowest sense of the word. You would have no perceptions, memories, thoughts, or feelings. We understand the world through our senses, our “windows” to the world. Our reality is dependent upon the two basic processes of sensation and perception. To understand this reality, we must first understand how we gather (sense) and interpret (perceive) the information that forms the foundation for our behavior and mental processing. Sensation and perception provide us with the information that allows us both to understand the world around us and to live in that world. Without them, there would be no world; there would be no “you.”

Perception does not exactly replicate the world outside. As Martinez-Conde and Macknik (2010, p. 4) point out, “It is a fact of neuroscience that everything we experience is actually a figment of our imagination. Although our sensations feel accurate and truthful, they do not necessarily reproduce the physical reality of the outside world.” Our “view” of the world is a subjective one that the brain constructs by using assumptions and principles, both built-in and developed from our past perceptual experiences (Hoffman, 1998). We perceive what the brain tells us we perceive. This means that sometimes our view of the world is inaccurate. Consider the tops of the two tables depicted in Figure 3.1. Do they appear to be the same shape and size? They don’t appear to be identical, but they are! If you trace one of the tabletops and then place the tracing on the other one, it will fit perfectly. As pointed out by Lilienfeld, Lynn, Ruscio, and Beyerstein (2010), “Seeing is believing, but seeing isn’t always believing correctly” (p. 7). We will revisit this illusion and its explanation later in the chapter; but, in general, this illusion is the result of the brain’s misinterpretation of perspective information about the two tables (Shepard, 1990). The important point for us is that the brain is misperceiving reality and that even with the knowledge that these two tabletops are identical, you will not be able to suppress the misperception your brain produces. What we perceive is generated by parts of the brain to which we do not have access. Your brain, not you, controls your perception of the world. The brain doesn’t work like a photocopy machine during perception. The brain interprets during perception; our perception is its interpretation. Beauty is not in the eye of the beholder, but rather in the brain of the beholder.

To understand how sensation and perception work, we must first look at how the physical world outside and the psychological world within relate to each other. This pursuit will take us back to the experimental roots of psychology and the work of nineteenth-century German researchers in psychophysics. These researchers were not psychologists but rather physiologists and physicists. They used experimental methods to measure the relationship between the physical properties of stimuli and a person’s psychological perception of those stimuli (hence the term psychophysics). Psychophysical researchers (psychophysicists) demonstrated that our mental activity could be measured quantitatively. Following a discussion of some of their major findings, we will take a look at how our two primary senses, vision and hearing, gather and process information from the environment, specifically focusing on how we see color and how we distinguish the pitch of a sound. Last, we will detail the general process of visual perception by examining how the brain organizes and recognizes incoming visual information, makes distance judgments to enable depth perception, and sometimes constructs misperceptions (illusions) as in Figure 3.1.