4.2 Learning Through Operant Conditioning

operant conditioning Learning to associate behaviors with their consequences. Behaviors that are reinforced (lead to satisfying consequences) will be strengthened, and behaviors that are punished (lead to unsatisfying consequences) will be weakened.

In the previous section, we described classical conditioning—

164

Research on how we learn associations between behaviors and their consequences started around the beginning of the twentieth century. American psychologist Edward Thorndike studied the ability of cats and other animals to learn to escape from puzzle boxes (Thorndike, 1898, 1911). In these puzzle boxes, there was usually only one way to get out (for example, pressing a lever would open the door). Thorndike would put a hungry animal in the box, place food outside the box (but in sight of the animal), and then record the animal’s behavior. If the animal pressed the lever, as a result of its behavior it would manage to escape the box and get the food (satisfying effects). The animal would tend to repeat such successful behaviors in the future when put back into the box. However, other behaviors (for example, pushing the door) that did not lead to escaping and getting the food would not be repeated.

law of effect A principle developed by Edward Thorndike that says that any behavior that results in satisfying consequences tends to be repeated and that any behavior that results in unsatisfying consequences tends not to be repeated.

Based on the results of these puzzle box experiments, Thorndike developed what he termed the law of effect—any behavior that results in satisfying consequences tends to be repeated, and any behavior that results in unsatisfying consequences tends not to be repeated. In the 1930s, B. F. (Burrhus Frederic) Skinner, the most influential of all behaviorists, redefined the law in more objective terms and started the scientific examination of how we learn through operant conditioning (Skinner, 1938). Let’s move on to Skinner’s redefinition and a description of how operant conditioning works.

Learning Through Reinforcement and Punishment

165

reinforcer A stimulus that increases the probability of a prior response.

punisher A stimulus that decreases the probability of a prior response.

reinforcement The process by which the probability of a response is increased by the presentation of a reinforcer.

punishment The process by which the probability of a response is decreased by the presentation of a punisher.

To understand how operant conditioning works, we first need to learn Skinner’s redefinitions of Thorndike’s subjective terms, “satisfying” and “unsatisfying” consequences. A reinforcer is defined as a stimulus that increases the probability of a prior response, and a punisher as a stimulus that decreases the probability of a prior response. Therefore, reinforcement is defined as the process by which the probability of a response is increased by the presentation of a reinforcer following the response, and punishment as the process by which the probability of a response is decreased by the presentation of a punisher following the response. “Reinforcement” and “punishment” are terms that refer to the process by which certain stimuli (consequences) change the probability of a behavior; “reinforcer” and “punisher” are terms that refer to the specific stimuli (consequences) that are used to strengthen or weaken the behavior.

Let’s consider an example. If you operantly conditioned your pet dog to sit by giving her a food treat each time she sat, the food treat would be the reinforcer, and the process of increasing the dog’s sitting behavior by using this reinforcer would be called reinforcement. Similarly, if you conditioned your dog to stop jumping on you by spraying her in the face with water each time she did so, the spraying would be the punisher, and the process of decreasing your dog’s jumping behavior by using this punisher would be called punishment.

Just as classical conditioning is best when the CS is presented just before the UCS, immediate consequences normally produce the best operant conditioning (Gluck, Mercado, & Myers, 2011). Timing affects learning. If there is a significant delay between a behavior and its consequences, conditioning is very difficult. This is true for both reinforcing and punishing consequences. The learner tends to associate reinforcement or punishment with recent behavior; and if there is a delay, the learner will have engaged in many other behaviors during the delay. Thus, a more recent behavior is more likely to be associated with the consequences, hindering the conditioning process. For instance, think about the examples we described of operantly conditioning your pet dog to sit or to stop jumping on you. What if you waited 5 or 10 minutes after she sat before giving her the food treat, or after she jumped on you before spraying her. Do you think your dog would learn to sit or stop jumping on you very easily? No, the reinforcer or punisher should be presented right after the dog’s behavior for successful conditioning.

Normally then, immediate consequences produce the best learning. However, there are exceptions. For example, think about studying now for a psychology exam in two weeks. The consequences (your grade on the exam) do not immediately follow your present study behavior. They come two weeks later. Or think about any job that you have had. You likely didn’t get paid immediately. Typically, you are paid weekly or biweekly. What is necessary to overcome the need for immediate consequences in operant conditioning is for the learner to have the cognitive capacity to link the relevant behavior to the consequences regardless of the delay interval between them. If the learner can make such causal links, then conditioning can occur over time lags between behaviors and their consequences.

166

appetitive stimulus A stimulus that is pleasant.

aversive stimulus A stimulus that is unpleasant.

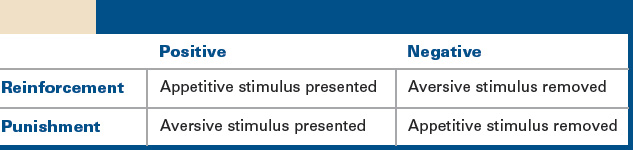

Positive and negative reinforcement and punishment. Both reinforcement and punishment can be either positive or negative, creating four new terms. Let’s see what is meant by each of these four new terms—

positive reinforcement Reinforcement in which an appetitive stimulus is presented.

positive punishment Punishment in which an aversive stimulus is presented.

Now that we know what positive and negative mean, and the difference between appetitive and aversive stimuli, we can understand the meanings of positive and negative reinforcement and punishment. General explanations for each type of reinforcement and punishment are given in Figure 4.4. In positive reinforcement, an appetitive stimulus is presented, but in positive punishment, an aversive stimulus is presented. An example of positive reinforcement would be praising a child for doing the chores. An example of positive punishment would be spanking a child for not obeying the rules.

167

negative reinforcement Reinforcement in which an aversive stimulus is removed.

negative punishment Punishment in which an appetitive stimulus is removed.

Similarly, in negative reinforcement and negative punishment, a stimulus is taken away. In negative reinforcement, an aversive stimulus is removed; in negative punishment, an appetitive stimulus is removed. An example of negative reinforcement would be taking Advil to get rid of a headache. The removal of the headache (an aversive stimulus) leads to continued Advil-

In all of these examples, however, we only know if a stimulus has served as a reinforcer or a punisher and led to reinforcement or punishment if the target behavior keeps occurring (reinforcement) or stops occurring (punishment). For example, the spanking would be punishment if the disobedient behavior stopped, and the praise reinforcement if the chores continued to be done. However, if the disobedient behavior continued, the spanking would have to be considered reinforcement; and if the chores did not continue to be done, the praise would have to be considered punishment. This is an important point. What serves as reinforcement or punishment is relative to each individual, in a particular context, and at a particular point in time. While it is certainly possible to say that certain stimuli usually serve as reinforcers or punishers, they do not inevitably do so. Think about money. For most people, $100 would serve as a reinforcer, but it might not for Bill Gates (of Microsoft), whose net worth is in the billions. Remember, whether the behavior is strengthened or weakened is the only thing that tells you whether the consequences were reinforcing or punishing, respectively.

Premack principle The principle that the opportunity to perform a highly frequent behavior can reinforce a less frequent behavior.

Given the relative nature of reinforcement, it would be nice to have a way to determine whether a certain event would function as a reinforcer. The Premack principle provides us with a way to make this determination (Premack, 1959, 1965). According to David Premack, you should view reinforcers as behaviors rather than stimuli (e.g., eating food rather than food). This enables the conceptualization of reinforcement as a sequence of two behaviors—

168

primary reinforcer A stimulus that is innately reinforcing.

secondary reinforcer A stimulus that gains its reinforcing property through learning.

Primary and secondary reinforcers. Behavioral psychologists make a distinction between primary and secondary reinforcers. A primary reinforcer is innately reinforcing, reinforcing since birth. Food and water are good examples of primary reinforcers. Note that “innately reinforcing” does not mean “always reinforcing.” For example, food would probably not serve as a reinforcer for someone who has just finished eating a five-

behavior modification The application of classical and operant conditioning principles to eliminate undesirable behavior and to teach more desirable behavior.

Behaviorists have employed secondary reinforcers in token economies in a variety of institutional settings, from schools to institutions for the mentally challenged (Allyon & Azrin, 1968). Physical objects, such as plastic or wooden tokens, are used as secondary reinforcers. Desired behaviors are reinforced with these tokens, which then can be exchanged for other reinforcers, such as treats or privileges. Thus, the tokens function like money in the institutional setting, creating a token economy. A token economy is an example of behavior modification—the application of conditioning principles, especially operant principles, to eliminate undesirable behavior and to teach more desirable behavior. Like token economies, other behavior modification techniques have been used successfully for many other tasks, from toilet training to teaching children who have autism (Kazdin, 2001).

Reinforcement without awareness. According to behavioral psychologists, reinforcement should strengthen operant responding even when people are unaware of the contingency between their responding and the reinforcement. Evidence that this is the case comes from a clever experiment by Hefferline, Keenan, and Harford (1959). Participants were told that the purpose of the study was to examine the effects of stress on body tension and that muscular tension would be evaluated during randomly alternating periods of harsh noise and soothing music. Electrodes were attached to different areas of the participants’ bodies to measure muscular tension. The duration of the harsh noise, however, was not really random. Whenever a participant contracted a very small muscle in their left thumb, the noise was terminated. This muscular response was imperceptible and could only be detected by the electrode mounted at the muscle. Thus, the participants did not even realize when they contracted this muscle.

169

There was a dramatic increase in the contraction of this muscle over the course of the experimental session. The participants, however, did not realize this, and none had any idea that they were actually in control of the termination of the harsh noise. This study clearly showed that operant conditioning can occur without a person’s awareness. It demonstrated this using negative reinforcement (an increase in the probability of a response that leads to the removal of an aversive stimulus). The response rate of contracting the small muscle in the left thumb increased and the aversive harsh noise was removed when the response was made. Such conditioning plays a big role in the development of motor skills, such as learning to ride a bicycle or to play a musical instrument. Muscle movements below our conscious level of awareness but key to skill development are positively reinforced by our improvement in the skill.

Pessiglione et al. (2008) provide a more recent demonstration of operant conditioning without awareness for a decision-

In this experiment, after being exposed to a masked contextual cue (an abstract novel symbol masked by a scrambled mixture of other cues) flashed briefly on a computer screen, a participant had to decide if he wanted to take the risky response or the safe response. The participant was told that the outcome of the risky response on each trial depended upon the cue hidden in the masked image. A cue could either lead to winning £1 (British currency), losing £1, or not winning or losing any money. If the participant took the safe response, it was a neutral outcome (no win or loss). Participants were also told that if they never took the risky response or always took it, their winnings would be nil and that because they could not consciously perceive the cues, they should follow their intuition in making their response decisions. All of the necessary precautions and assessments to ensure that participants did not perceive the masked cues were taken. Overall, participants won money in the task, indicating that the risky response was more frequently chosen following reinforcement predictive cues relative to punishment predictive cues.

In addition to this recent demonstration of operant conditioning without awareness, there have been several demonstrations of classical conditioning without awareness (Clark & Squire, 1998; Knight, Nguyen, & Bandettini, 2003; Morris, Öhman, & Dolan, 1998; Olsson & Phelps, 2004). Using delayed conditioning, Clark and Squire, for example, successfully conditioned the eyeblink response in both normal and amnesic participants who were not aware of the tone–

170

General Learning Processes in Operant Conditioning

Now that we have a better understanding of how we learn through reinforcement and punishment, let’s consider the five general learning processes in operant conditioning that we discussed in the context of classical conditioning—

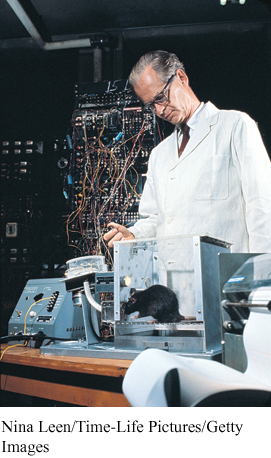

For control purposes, behavioral psychologists conduct much of their laboratory research on nonhuman animals. In conducting their experiments with animals, operant conditioning researchers use operant chambers, which resemble large plastic boxes. These chambers are far from simple boxes, though. Each chamber has a response device (such as a lever for rats to press or a key for pigeons to peck), a variety of stimulus sources (such as lamps behind the keys to allow varying colors to be presented on them), and food dispensers. Here, “key” refers to a piece of transparent plastic behind a hole in the chamber wall. The key or other response device is connected to a switch that records each time the animal responds. Computers record the animal’s behavior, control the delivery of food, and maintain other aspects of the chamber. Thus, the operant chamber is a very controlled environment for studying the impact of the animal’s behavior on its environment. Operant chambers are sometimes referred to as “Skinner boxes” because B. F. Skinner originally designed this type of chamber.

shaping Training a human or animal to make an operant response by reinforcing successive approximations of the desired response.

What if the animal in the chamber does not make the response that the researcher wants to condition (for example, what if the pigeon doesn’t peck the key)? This does happen, but behavioral researchers can easily deal with this situation. They use what they call shaping; they train the animal to make the response they want by reinforcing successive approximations of the desired response. For example, consider the key-

171

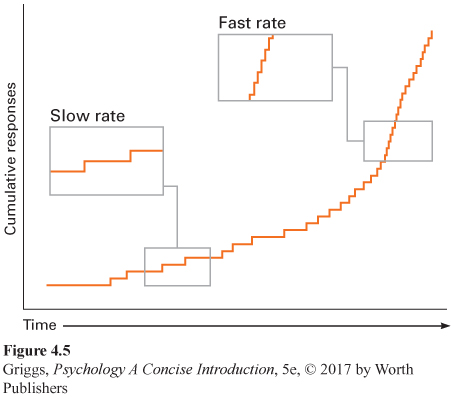

cumulative record A record of the total number of operant responses over time that visually depicts the rate of responding.

Responding in an operant conditioning experiment is depicted in a cumulative record. A cumulative record is a record of the total number of responses over time. As such, it provides a visual depiction of the rate of responding. Figure 4.5 shows how to read a cumulative record. The slope of the record indicates the response rate. Remember that the record visually shows how the responses cumulate over time. If the animal is making a large number of responses per unit of time (a fast response rate), the slope of the record will be steep. The cumulative total is increasing quickly. When there is no responding (the cumulative total remains the same), the record is flat (no slope). As the slope of the record increases, the response rate gets faster. Now let’s see what cumulative records look like for some of the general learning processes.

acquisition (in operant conditioning) The strengthening of a reinforced operant response.

extinction (in operant conditioning) The diminishing of the operant response when it is no longer reinforced.

spontaneous recovery (in operant conditioning) The temporary recovery of the operant response following a break during extinction training.

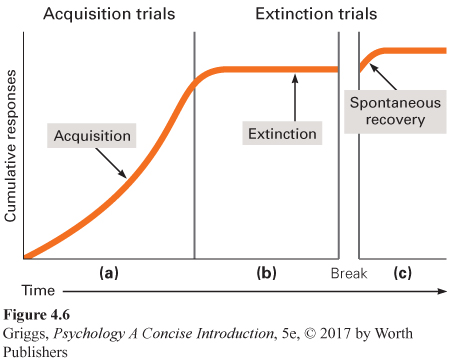

Acquisition, extinction, and spontaneous recovery. The first general process, acquisition, refers to the strengthening of the reinforced operant response. What would this look like on the cumulative record? Figure 4.6(a) shows that the response rate increases over time. This looks very similar to the shape of the acquisition figure for classical conditioning (see Figure 4.2), but remember the cumulative record is reporting cumulative responding as a function of time, not the strength of the response. Thus, extinction, the diminishing of the operant response when it is no longer reinforced, will look different than it did for classical conditioning. Look at Figure 4.6(b). The decreasing slope of the record indicates that the response is being extinguished; there are fewer and fewer responses over time. The response rate is diminishing. When the record goes to flat, extinction has occurred. However, as in classical conditioning, there will be spontaneous recovery, the temporary recovery of the operant response following a break during extinction training. This would be indicated in the record by a brief period of increased responding following a break in extinction training. However, the record would go back to flat (no responding) as extinction training continued. This is shown in Figure 4.6(c).

172

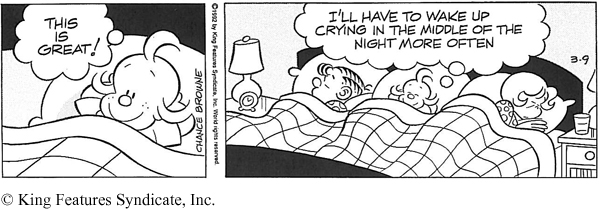

Let’s think about acquisition, extinction, and spontaneous recovery with an example that is familiar to all of us—

discriminative stimulus (in operant conditioning) The stimulus that has to be present for the operant response to be reinforced.

stimulus discrimination (in operant conditioning) Learning to give the operant response only in the presence of the discriminative stimulus.

Discrimination and generalization. Now let’s consider discrimination and generalization. To understand discrimination in operant conditioning, we need first to consider the discriminative stimulus—the stimulus that has to be present for the operant response to be reinforced or punished. The discriminative stimulus “sets the occasion” for the response to be reinforced or punished (rather than elicits the response as in classical conditioning). Here’s an example. Imagine a rat in an experimental operant chamber. When a light goes on and the rat presses the lever, food is delivered. When the light is not on, pressing the lever does not lead to food delivery. In brief, the rat learns the conditions under which pressing the lever will be reinforced with food. This is stimulus discrimination—learning to give the operant response (pressing the lever) only in the presence of the discriminative stimulus (the light). A high response rate in the presence of the discriminative stimulus (the light) and a near-

173

stimulus generalization (in operant conditioning) Giving the operant response in the presence of stimuli similar to the discriminative stimulus. The more similar the stimulus is to the discriminative stimulus, the higher the operant response rate.

Now we can consider stimulus generalization, giving the operant response in the presence of stimuli similar to the discriminative stimulus. Let’s return to the example of the rat learning to press the lever in the presence of a light. Let’s make the light a shade of green and say that the rat learned to press the lever only in the presence of that particular shade of green light. What if the light were another shade of green, or a different color, such as yellow? Presenting similar stimuli (different-

Stimulus discrimination and generalization in operant conditioning are not confined to using simple visual and auditory stimuli such as colored lights and varying tones, even for animals other than humans. For example, Watanabe, Sakamoto, and Wakita (1995) showed that pigeons could successfully learn to discriminate paintings by Monet, an impressionist, and Picasso, a cubist; and that following this training, they could discriminate paintings by Monet and Picasso that had never been presented. Furthermore, the pigeons showed generalization from Monet’s paintings to paintings by other impressionists (Cézanne and Renoir) or from Picasso’s paintings to paintings by other cubists (Braque and Matisse). In addition, Porter and Neuringer (1984) have reported successful learning of musical discrimination between selections by Bach versus Stravinsky by pigeons followed by generalization to music by similar composers. Otsuka, Yanagi, and Watanabe (2009) similarly showed that even rats could learn this musical discrimination between selections by Bach versus those by Stravinsky. Thus, like humans, other animals can clearly learn to discriminate complex visual and auditory stimuli and then generalize their learning to similar stimuli.

174

All five of the general learning processes for operant conditioning are summarized in Table 4.2. If any of these processes are not clear to you, restudy the discussions of those processes in the text to solidify your understanding. Also make sure that you understand how these learning processes in operant conditioning differ from those in classical conditioning (summarized in Table 4.1).

| Learning Process | Explanation of Process |

|---|---|

| Acquisition | Strengthening of a reinforced operant response |

| Extinction | Diminishing of the operant response when it is no longer reinforced |

| Spontaneous recovery | Temporary recovery in the operant response rate following a break during extinction training |

| Stimulus generalization | Giving the operant response in the presence of stimuli similar to the discriminative stimulus (the more similar, the higher the response rate) |

| Stimulus discrimination | Learning to give the operant response only in the presence of the discriminative stimulus |

Now that we understand the general processes involved in operant conditioning, we need to consider the question of how operant responding is maintained following acquisition. Will the responding be maintained if it is reinforced only part of the time? If so, what’s the best way to do this? Such questions require an understanding of what are called reinforcement schedules.

Partial-

continuous schedule of reinforcement Reinforcing the desired operant response each time it is made.

partial schedule of reinforcement Reinforcing the desired operant response only part of the time.

partial-

The reinforcement of every response is called a continuous schedule of reinforcement. But we aren’t reinforced for every response in everyday life. In real life, we experience partial schedules of reinforcement, in which a response is only reinforced part of the time. Partial-

175

Partial-

fixed-

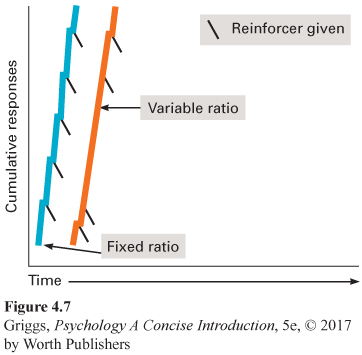

Ratio schedules. In a fixed-

variable-

In a variable-

176

Ratio schedules lead to high rates of responding because the number of responses determines reinforcement; the more they respond, the more they are reinforced. Cumulative records for the two ratio schedules are given in Figure 4.7. The slopes for the two ratio schedules are steep, which indicates a high rate of responding. Look closely after each reinforcement presentation (indicated by a tick mark), and you will see very brief pauses after reinforcement, especially for the fixed-

fixed-

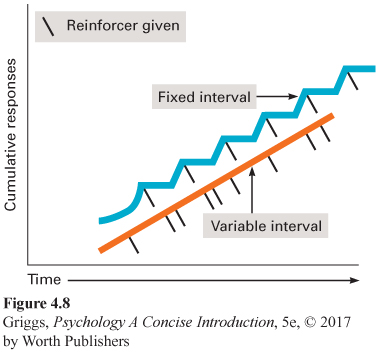

Interval schedules. Now let’s consider interval schedules. Do you think the cumulative records for the two interval schedules will have steep slopes like the two ratio schedules? Will there be any flat sections in the record indicating no responding? Let’s see. In a fixed-

177

In most of your classes, you are given periodic scheduled exams (for example, an exam every four weeks). To understand how such periodic exams represent a fixed-

variable-

Now imagine that you are the teacher of a class in which students had this pattern of study behavior. How could you change the students’ study behavior to be more regular? The answer is to use a variable-

178

The four types of partial-

| Schedule | Effect on Response Rate |

|---|---|

| Fixed- |

High rate of responding with pauses after receiving reinforcement |

| Variable- |

High rate of responding with fewer pauses after receiving reinforcement than for a fixed- |

| Fixed- |

Little or no responding followed by a high rate of responding as the end of the interval nears |

| Variable- |

Steady rate of responding during the interval |

Let’s compare the cumulative records for the four types of partial-

Now let’s think about partial-

179

Do you think there are any differences in this resistance to extinction between the various partial schedules of reinforcement? Think about the fixed schedules versus the variable schedules. Wouldn’t it be much more difficult to realize that something is wrong on a variable schedule? On a fixed schedule, it would be easy to notice that the reinforcement didn’t appear following the fixed number of responses or fixed time interval. On a variable schedule, however, the disappearance of reinforcement would be very difficult to detect because it’s not known how many responses will have to be made or how much time has to elapse. Think about the example of a variable-

Motivation, Behavior, and Reinforcement

motivation The set of internal and external factors that energize our behavior and direct it toward goals.

We have just learned about how reinforcement works and that partial-

drive-

Theories of motivation. One explanation of motivation, drive-

180

incentive theory A theory of motivation that proposes that our behavior is motivated by incentives, external stimuli that we have learned to associate with reinforcement.

In contrast to being “pushed” into action by internal drive states, the incentive theory of motivation proposes that we are “pulled” into action by incentives, external environmental stimuli that do not involve drive reduction. The source of the motivation, according to incentive theory, is outside the person. Money is an incentive for almost all of us. Good grades and esteem are incentives that likely motivate much of your behavior to study and work hard. Incentive theory is much like operant conditioning. Your behavior is directed toward obtaining reinforcement.

arousal theory A theory of motivation that proposes that our behavior is motivated to maintain an optimal level of physiological arousal

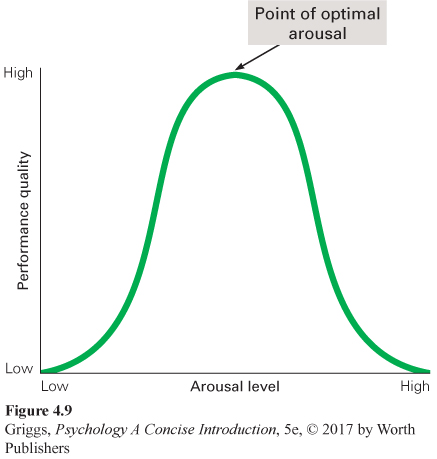

Another explanation of motivation, arousal theory, extends the importance of a balanced internal environment in drive-

Yerkes-

In addition, arousal theory argues that our level of arousal affects our performance level, with a certain level being optimal. Usually referred to as the Yerkes-

To solidify your understanding of these three theories of motivation, they are summarized in Table 4.4.

181

| Theory | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Drive- |

Our behavior is motivated to reduce drives (bodily tension states) created by unsatisfied bodily needs to return the body to a balanced internal state |

| Incentive theory | Our behavior is motivated by incentives (external stimuli that we have learned to associate with reinforcement) |

| Arousal theory | Our behavior is motivated to maintain an optimal level of physiological arousal |

extrinsic motivation The desire to perform a behavior for external reinforcement.

intrinsic motivation The desire to perform a behavior for its own sake.

Extrinsic motivation versus intrinsic motivation. Motivation researchers make a distinction between extrinsic motivation, the desire to perform behavior to obtain an external reinforcer or to avoid an external aversive stimulus, and intrinsic motivation, the desire to perform a behavior for its own sake. In cases of extrinsic motivation, reinforcement is not obtained from the behavior, but is a result of the behavior. In intrinsic motivation, the reinforcement is provided by the activity itself. Think about what you are doing right now. What is your motivation for studying this material? Like most students, you want to do well in your psychology class. You are studying for an external reinforcer (a good grade in the class), so your behavior is extrinsically motivated. If you enjoy reading about psychology and studying it for its own sake and not to earn a grade (and I hope that you do), then your studying would be intrinsically motivated. It is not an either-

overjustification effect A decrease in an intrinsically motivated behavior after the behavior is extrinsically reinforced and then the reinforcement is discontinued.

The reinforcers in cases of extrinsic motivation—

182

The overjustification effect has been demonstrated for people of all ages, but let’s consider an example from a study with nursery-

In our example, extrinsic reinforcement (the awards for the children) provides unnecessary justification for engaging in the intrinsically motivated behavior (drawing with the felt-

The overjustification effect indicates that a person’s cognitive processing influences their behavior and that such processing may lessen the effectiveness of extrinsic reinforcers. Don’t worry, though, about the overjustification effect influencing your study habits (assuming that you enjoy studying). Research has shown that performance-

183

The overjustification effect imposes a limitation on operant conditioning and its effectiveness in applied settings. It tells us that we need to be careful in our use of extrinsic motivation so that we do not undermine intrinsic motivation. It also tells us that we must consider the possible cognitive consequences of using extrinsic reinforcement. In the next section, we continue this limitation theme by first considering some biological constraints on learning and then some cognitive research that shows that reinforcement is not always necessary for learning.

Section Summary

In this section, we learned about operant conditioning, in which the rate of a particular response depends on its consequences, or how it operates on the environment. Immediate consequences normally produce the best operant conditioning, but there are exceptions to this rule. If a particular response leads to reinforcement (satisfying consequences), the response rate increases; if a particular response leads to punishment (unsatisfying consequences), the rate decreases. In positive reinforcement, an appetitive (pleasant) stimulus is presented, and in negative reinforcement, an aversive (unpleasant) stimulus is removed. In positive punishment, an aversive (unpleasant) stimulus is presented; in negative punishment, an appetitive (pleasant) stimulus is removed.

In operant conditioning, cumulative records (visual depictions of the rate of responding) are used to report behavior. Reinforcement is indicated by an increased response rate on the cumulative record, and extinction (when reinforcement is no longer presented) is indicated by a diminished response rate leading to no responding (flat) on the cumulative record. As in classical conditioning, spontaneous recovery of the response (a temporary increase in response rate on the cumulative record) is observed following breaks in extinction training. Discrimination and generalization involve the discriminative stimulus, the stimulus in whose presence the response will be reinforced. Thus, discrimination involves learning when the response will be reinforced. Generalization involves responding in the presence of stimuli similar to the discriminative stimulus—

We learned about four different schedules of partial reinforcement—

We also learned about motivation, which moves us toward reinforcement by initiating and guiding our goal-

184

We also learned about the overjustification effect, in which extrinsic (external) reinforcement sometimes undermines intrinsic motivation, the desire to perform a behavior for its own sake. In the overjustification effect, there is a substantial decrease in an intrinsically motivated behavior after this behavior is extrinsically reinforced and then the reinforcement is discontinued. This effect seems to be the result of the cognitive analysis that a person conducts to determine the true motivation for their behavior. The importance of the extrinsic reinforcement is overemphasized in this cognitive analysis, leading the person to stop engaging in the behavior. Thus, the overjustification effect imposes a cognitive limitation on operant conditioning and its effectiveness.

2

Question 4.5

.

Explain what “positive” means in positive reinforcement and positive punishment and what “negative” means in negative reinforcement and negative punishment.

“Positive” refers to the presentation of a stimulus. In positive reinforcement, an appetitive stimulus is presented; in positive punishment, an aversive stimulus is presented. “Negative” refers to the removal of a stimulus. In negative reinforcement, an aversive stimulus is removed; in negative punishment, an appetitive stimulus is removed.

Question 4.6

.

Explain why it is said that the operant response comes under the control of the discriminative stimulus.

The operant response comes under the control of the discriminative stimulus because it is only given in the presence of the discriminative stimulus. The animal or human learns that the reinforcement is only available in the presence of the discriminative stimulus.

Question 4.7

.

Explain why a cumulative record goes to flat when a response is being extinguished.

A cumulative record goes flat when a response is extinguished because no more responses are made; the cumulative total of responses remains the same over time. Thus, the record is flat because this total is not increasing at all. Remember that the cumulative record can never decrease because the total number of responses can only increase.

Question 4.8

.

Explain why the partial-

The partial-

Question 4.9

.

Explain why the overjustification effect is a cognitive limitation on operant conditioning.

The overjustification effect is a cognitive limitation on operant conditioning because it is the result of a person’s cognitive analysis of their true motivation (extrinsic versus intrinsic) for engaging in an activity. In this analysis, the person overemphasizes the importance of the extrinsic reinforcement. For example, the person might now view the extrinsic reinforcement as an attempt at controlling their behavior and stop the behavior to maintain their sense of choice.