5.3 Retrieving Information from Memory

In the last section, we focused on how to encode information into long-

How to Measure Retrieval

recall A measure of long-

recognition A measure of long-

relearning The savings method of measuring long-

The three main methods for measuring our ability to retrieve information from long-

226

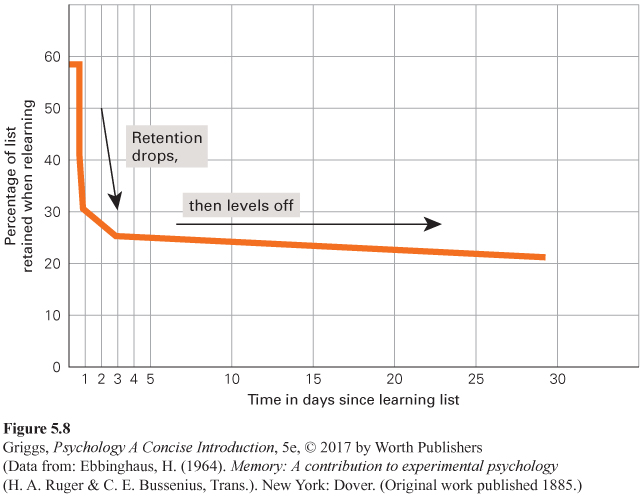

Hermann Ebbinghaus conducted the first experimental studies on human memory more than 100 years ago in Germany using the relearning method (Ebbinghaus, 1885/1964). His stimulus materials were lists of nonsense syllables, groupings of three letters (consonant-

To get a measure of relearning, Ebbinghaus computed what he called a savings score—

Why We Forget

There is no question that we forget. Our memories clearly fail us. This is especially problematic for exams. Haven’t we all taken an exam and forgotten some information and then retrieved it after the exam was over? To understand forgetting, we must confront two questions. First, why do we forget? Second, do we really ever truly forget or do we just fail to retrieve information at a particular point in time? To answer these questions, we’ll take a look at four theories of forgetting—

227

encoding failure theory A theory of forgetting that proposes that forgetting is due to the failure to encode the information into long-

Encoding failure theory states that sometimes forgetting is not really forgetting but rather encoding failure (sometimes called pseudoforgetting). The information in question never entered long-

228

Now let’s test your memory for an everyday object that has a less detailed design than a penny, the Apple logo, which has often been referred to as one of the most recognizable logos in the world. Without sneaking a glance at any Apple products that may be near you, try to draw the Apple logo from memory. Once you have done so, look up the logo online to determine if your drawing is correct. If it isn’t, don’t feel bad. Blake, Nazarian, and Castel (2015) recently asked some UCLA students, the vast majority being Apple users or primarily Apple users, first to recall (draw) the Apple logo from memory and then later to recognize the correct Apple logo in an array including it and other similar but incorrect logos. Only 1 student out of 85 could draw the logo correctly, and less than 50% could identify it in an array of similar logos. Like Nickerson and Adams’s participants who had not encoded the details of the penny, the UCLA students had not encoded the details of the Apple logo. Given that we do not seem to remember details unless we consciously make an effort to encode them, make sure that you do encode them in studying for your exams. If the details are not encoded, then they cannot be remembered.

storage decay theory A theory of forgetting that proposes that forgetting is due to the decay of the biological representation of the information and that periodic usage of the information will help to maintain it in storage.

The other three theories of forgetting deal with information that was encoded into long-

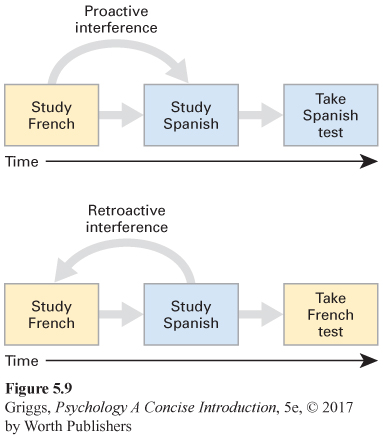

interference theory A theory of forgetting that proposes that forgetting is due to other information in memory interfering and thereby making the to-

proactive interference The disruptive effect of prior learning on the retrieval of new information.

retroactive interference The disruptive effect of new learning on the retrieval of old information.

The other two theories of forgetting propose that there are retrieval problems and not problems with storage. Both assume that the forgotten information is still available in long-

229

cue-

tip-

Cue-

230

So, there are many reasons why we forget. The four major theories are summarized in Table 5.2, but how can you apply this knowledge to enhance your learning? First, sometimes we forget because we do not encode the information into long-

| Theory | Explanation of Forgetting |

|---|---|

| Encoding failure theory | Forgetting is due to the failure to encode the information into long- |

| Storage decay theory | Forgetting is due to the decay of the biological representation of the information in long- |

| Interference theory | Forgetting is due to the interference of other information in long- |

| Cue- |

Forgetting is due to the unavailability of the retrieval cues necessary to locate the information in long- |

The next section concerns the information that we do retrieve. Is it accurate or is it distorted? The answer is that it is often distorted. How does this occur? It occurs because retrieval is reconstructive and not exact. Let’s take a look at the retrieval process to see how its reconstructive nature may distort our memories.

The Reconstructive Nature of Retrieval

231

The act of remembering is an act of reconstruction. Memory does not work like a tape recorder or a video recorder. Retrieval is not like playback. Our memories are far from exact replicas of past events. If you read a newspaper this morning, do you remember the stories that you read in the paper word for word? We usually encode the gist or main theme of the story along with some of the story’s highlights. Then, when we retrieve the information from our memory, we reconstruct a memory of the story using the theme and the highlights.

schemas Frameworks for our knowledge about people, objects, events, and actions that allow us to organize and interpret information about our world.

Our retrieval reconstruction is guided by what are called schemas—frameworks for our knowledge about people, objects, events, and actions. These schemas allow us to organize our world. For example, what happens when you enter a dentist’s office or what happens when you go to a restaurant to eat? You have schemas in your memory for these events. The schemas tell us what normally happens. For example, consider the schema for eating out in a restaurant (Schank & Abelson, 1977). First, a host or hostess seats you and gives you a menu. Then the waitperson gets your drink order, brings your drinks, and then takes your meal order. Your food arrives, you eat it, the waitperson brings the bill. You pay it, leave a tip, and go. These schemas allow us to encode and retrieve information about the world in a more organized, efficient manner.

The first experimental work on schemas and their effects on memory was conducted by Sir Frederick Bartlett in the first half of the twentieth century (Bartlett, 1932). Bartlett had his participants study some stories that were rather unusual. He then tested their memory for these stories at varying time intervals. When the participants recalled the stories, they made them more consistent with their own schemas about the world. For example, one story did not say anyone was wounded in the battle described, but participants recalled that many men were wounded, fitting their schemas for battles. Unusual details were normalized. For example, participants recalled incorrectly that the men in another story were fishing rather than hunting seals. In addition, the stories were greatly shortened in length when recalled. Strangely, the participants did not even realize that they were changing many of the details of the stories. In fact, the parts that they changed were those that they were most confident about remembering.

232

Bartlett’s participants had reconstructed the stories using their schemas and did not even realize it. The main point to remember is that they distorted the stories in line with their schemas. Why? Schemas allow us to encode and retrieve information more efficiently. It would be impossible to encode and retrieve the exact details of every event in our lives. That’s why we need organizing schemas to guide us in this task, even though they do not provide an exact copy of what happened. This seems a small cost given the benefits provided by organizing memory in terms of schemas.

source misattribution Attributing a memory to the wrong source, resulting in a false memory.

Memory can be further distorted in reconstruction by source misattribution and the misinformation effect. Source misattribution occurs when we do not remember the true source of a memory and attribute the memory to the wrong source. Maybe you dream something and then later misremember that it actually happened. You misattribute the source to actual occurrence rather than occurrence in a dream. Source information for memories is not very good. You need to beware of this when writing papers. You may unintentionally use another person’s ideas and think they are yours. You have forgotten their source. Even if source misattribution is unintentional, it is still plagiarism. Source misattribution also helps to explain déjà vu, that eerie sense that you have been in the exact same situation before, but in actuality you have not (Cleary, 2008). You have a feeling of familiarity because you have previously experienced elements in the situation in other contexts, but you cannot make the correct source attributions for them. Thus, déjà vu may result from feelings of familiarity that occur in a new situation without proper identification of their sources.

false memory An inaccurate memory that feels as real as an accurate memory.

Source misattribution can also lead to other problems. A famous case of source misattribution involved noted developmental psychologist Jean Piaget (Loftus & Ketcham, 1991). For much of his life, Piaget believed that when he was a child, his nursemaid had thwarted an attempt to kidnap him. He remembered the attempt, even remembered the details of the event. When the nursemaid finally admitted to making up the story, Piaget couldn’t believe it. He had reconstructed the event from the many times the nursemaid recounted the incident and had misattributed the source to actual occurrence. This is like thinking that something we dreamed really occurred. The source of the memory is misattributed. Source misattribution results in what is called a false memory, an inaccurate memory that feels as real as an accurate memory. False memories can also be the result of imagination and observation inflation and the misinformation effect.

233

Imagination inflation is increased confidence in a false memory of an event caused by repeatedly imagining the event. For example, imagining performing an action often induces a false memory of having actually performed it (Garry, Manning, Loftus, & Sherman, 1996; Goff & Roediger, 1998). Repeated imagining inflates the confidence the person has that he actually performed the action, the imagination inflation effect. What might cause this disconcerting memory failure? Several factors likely contribute to the formation of these false memories. First, actually perceiving something and imagining it activate the same brain areas, leading to similar neural events that when tested might cause confusion as to whether the event was imagined or real (Gonsalves et al., 2004). Second, repeatedly imagining an event makes it seem increasingly familiar. This sense of familiarity can then be misinterpreted as evidence that the event actually occurred (Sharman, Garry, & Beuke, 2004). Lastly, the more vividly we are able to imagine events, the more likely it is that the imagined events feel like real events (Loftus, 2001; Thomas, Bulevich, & Loftus, 2003).

There is now evidence for a similar false memory effect in which a false memory of self-

234

misinformation effect The distortion of a memory by exposure to misleading information.

The misinformation effect occurs when a memory is distorted by subsequent exposure to misleading information (Loftus, 2005). Elizabeth Loftus and her colleagues have provided numerous demonstrations of the misinformation effect, involving thousands of subjects, over the past four decades (Frenda, Nichols, & Loftus, 2011). These studies usually involve witnessing an event and then being tested for memory of the event but being given misleading information at the time of the test. Let’s consider an example. Loftus and John Palmer (1974) showed participants a film of a traffic accident and then later tested their memory for the accident. The test included misleading information for some of the participants. For example, some participants were asked, “How fast were the cars going when they smashed into each other?” and others were asked, “How fast were the cars going when they hit each other?” Participants who were asked the question with the word “smashed” estimated the speed to be much higher than those who were asked the question with the word “hit.” In addition, when brought back a week later, those participants who had been questioned with the word “smashed” more often thought that they had seen broken glass in the accident when in fact there was none. The key theme of this line of research is that our memories for events are distorted by exposure to misinformation. The resulting false memories seem like real memories.

False memories have important implications for use of eyewitness testimony in criminal cases and for the controversy over memories of childhood sexual abuse that have supposedly been repressed but then are “recovered” in adulthood. The Loftus and Palmer research example shows us that eyewitness testimony is subject to error and manipulation by misleading information. Between 1989 and 2007, for example, 201 prisoners in the United States were freed because of DNA evidence; and 77% of these prisoners had been mistakenly identified by eyewitnesses (Hallinan, 2009). Many of these overturned cases rested on the testimony of two or more mistaken eyewitnesses. Eyewitnesses not only often misidentify innocent people as criminals but they also often do so with the utmost confidence, and jurors tend to heavily weigh an eyewitness’s confidence when judging their believability.

235

Clearly, certain types of interrogation, including the way questions are worded, could lead to false memories. With respect to the repressed memory controversy, many memory researchers are skeptical and think that these “recovered” memories may describe events that never occurred (like the kidnapping attempt on Piaget as a child). Instead, they may be false memories that have been constructed and may even have been inadvertently implanted by therapists during treatment sessions. In fact, researchers have demonstrated that such implanting is possible (Loftus, Coan, & Pickrell, 1996; Loftus & Ketcham, 1994). We must remember, however, that demonstrating the possibility of an event does not demonstrate that it actually happened. So, are all memories of childhood sexual abuse false? Absolutely not. Sexual abuse of all kinds is unfortunately all too real. The important point for us is that the research on false memory has provided empirical evidence to support an alternative explanation to the claims for recovered memories, and this will help to sort out the true cases from the false.

Section Summary

In this section, we considered the three ways to measure retrieval—

There are four major theories that address the question of why we forget. Encoding failure theory assumes that the information is never encoded into long-

Memory is a reconstructive process guided by our schemas—

236

3

Question 5.8

.

Explain the difference between recall and recognition as methods to measure retrieval.

In recall, the information has to be reproduced. In recognition, the information only has to be identified.

Question 5.9

.

Explain how the four major theories of forgetting differ with respect to the availability versus accessibility of the forgotten information.

Encoding failure theory and storage decay theory assume the forgotten information is not available in long-

Question 5.10

.

Explain how schemas help to create false memories.

Schemas help to create false memories because in using them, we tend to replace the actual details of what happened with what typically happens in the event that the schema depicts. As Bartlett found in his schema research, this is especially true for unusual details. This means that schemas tend to normalize our memories and lead us to remember what usually happens and not exactly what did happen.

Question 5.11

.

Explain how source misattribution and the misinformation effect lead to false memories.

Source misattribution leads to false memories because we don’t really know the source of a memory. The event may never have occurred, but we think that it did because we misattributed the source of the memory. The misinformation effect leads to false memories through the effect of misleading information being given at the time of retrieval. We incorporate this misleading information for an event into our memory and thus create a false memory for it.