8.2 The Humanistic Approach and the Social-Cognitive Approach to Personality

Humanistic theories of personality developed during the 1960s as part of the general humanistic movement in psychology. The humanistic movement was in response to the deterministic psychoanalytic and strict behavioral psychological approaches that dominated psychology and the study of personality at that time. As we just discussed, the classical psychoanalytic approach assumes that personality is a product of how the id’s unconscious instinctual drives find satisfaction, especially during the first three psychosexual stages. The strict behavioral approach assumes that our personality and behavior are merely products of our environment, as a result of classical and operant conditioning (discussed in Chapter 4). Our personality is determined by our behavior and is conditioned by environmental events. According to both approaches, we are not in charge of our behavior and personality development. According to the psychoanalytic approach, our unconscious instinctual drives are the major motivators of our behavior and personality development. According to the behavioral approach, the environment motivates and controls our actions. In contrast, the humanistic approach emphasizes conscious free will in one’s actions, the uniqueness of the individual person, and personal growth. Unlike the psychoanalytic approach’s focus on our personality problems, the humanistic approach centers on the positive motivations for our actions and development, especially personal growth. To familiarize you with this approach, we will describe the theories of the two major humanistic proponents, Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers.

At about the same time as the humanists, social-cognitive theorists rebelled against the narrowness of the strict behavioral approach to the development of personality. The behavioral approach limited itself to the factors of classical and operant conditioning for learning behaviors (personality). Social-cognitive theorists agreed that conditioning was important, but thought that the situation was more complex than that. Remember, Albert Bandura’s work on social (observational) learning in Chapter 4 demonstrated our ability to learn from observing others without direct reinforcement, which meant that social and cognitive factors were involved in learning. The social-cognitive approach includes social and cognitive factors along with conditioning to explain personality development. Thus, the strict behavioral approach to personality is subsumed under the more extensive social-cognitive approach. Because of this, the social-cognitive approach is sometimes referred to as the social-learning approach and the cognitive-behavioral approach. We refer to it as the social-cognitive approach here in order to note its emphasis on these two types of factors in personality development. We will describe some of the theoretical concepts of two important social-cognitive theorists, Albert Bandura and Julian Rotter, to illustrate why they think social and cognitive factors are important in personality development.

The Humanistic Approach to Personality

Abraham Maslow

© Corbis

Abraham Maslow is considered the father of the humanistic movement. He studied the lives of very healthy and creative people to develop his theory of personality. His main theoretical emphases were psychological health and reaching one’s full potential. In describing how one goes about reaching one’s full potential, Maslow proposed a hierarchy of needs that motivate our behavior in this quest. Because of the motivating role of these various types of needs, Maslow’s personality theory is also considered a theory of motivation.

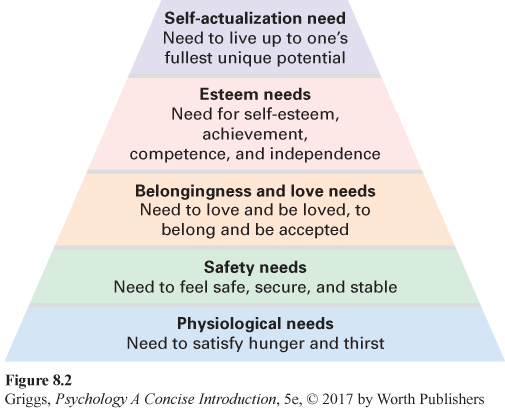

hierarchy of needs The motivational component in Maslow’s theory of personality, in which our innate needs that motivate our behavior are hierarchically arranged in a pyramid shape. From bottom to top, the needs are physiological, safety, belonging and love, esteem, and self-actualization.

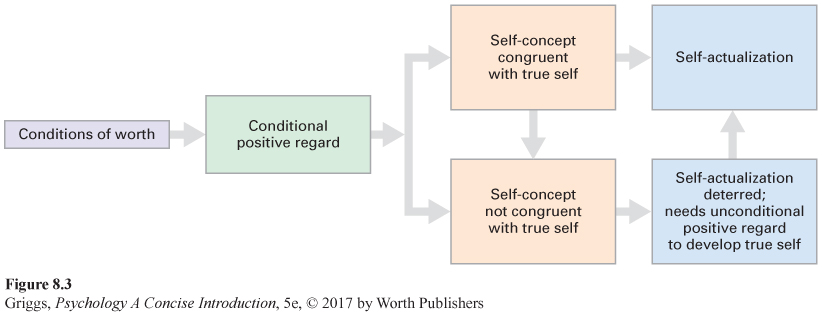

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. An overview of Maslow’s motivational hierarchy of needs, which is often depicted as a pyramid-like structure, is given in Figure 8.2. The hierarchy of needs is an arrangement of the innate needs that motivate behavior, from the strongest needs at the bottom of the pyramid to the weakest needs at the top of the pyramid (Maslow, 1968, 1970). From bottom to top, the needs are physiological, safety, belonging and love, esteem, and self-actualization. For obvious practical reasons, motivation proceeds from the bottom of the hierarchy to the top; lower needs are more urgent and have to be satisfied before higher needs can even be considered. On average, people seem to work their way up the hierarchy, but they also work on several levels simultaneously. The level at which the person is investing most of his effort is the one most important to a person at a particular point in time.

Figure 8.2: Figure 8.2 | Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs | Needs are organized hierarchically into levels, with more pressing basic needs at the bottom of the pyramid. The level at which a person is investing most of his effort is the most important one at that particular point in time.

As you move up in the hierarchy, the needs become more human and less basic. The most basic needs are physiological needs (such as for food and water); therefore, they form the base of the pyramid structure. At the next level, the needs to feel safe, secure, and out of danger are also relevant to our survival, but not quite as basic as physiological needs. At the next level in the hierarchy, however, needs begin to have social aspects. Love and belongingness needs (needs for affection, acceptance, family relationships, and companionship) are met through interactions with other people. Self-esteem needs at the next level in the hierarchy are concerned with achievement, mastery, and gaining appreciation from others for our achievements, as well as developing a positive self-image.

self-actualization The fullest realization of a person’s potential.

These first four levels of needs are more deficiency-based needs, stemming from deprivation, while self-actualization at the top of the hierarchy is a growth-based need. Self-actualization is the fullest realization of a person’s potential, becoming all that one can be. According to Maslow, the characteristics of self-actualized people include accepting themselves, others, and the natural world for what they are; having a need for privacy and only a few very close, emotional relationships; and being autonomous and independent, unquestionably democratic, and very creative. In addition, self-actualized people have what Maslow termed “peak experiences”—moments of deep insight in which you experience whatever you are doing as fully as possible. In peak experiences, you are deeply immersed in what you are doing and feel a sense of awe and wonder. Peak experiences might, for example, arise from great music or art, or from intense feelings of love.

Maslow based his description of self-actualization on his study of about 50 people who he deemed “self-actualized.” Some, such as Albert Einstein and Eleanor Roosevelt, were living, so he studied them through interviews and personality tests, but others, such as Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln, were not, so he used biographies and historical records to study them. Maslow was rather vague about how he conducted these “studies,” however. Maslow’s theory has been criticized for being based on nonempirical, imprecise studies of a small number of people that he subjectively selected as self-actualized (Smith, 1978). His theory may have been biased toward his own idea of a healthy, self-actualized person. Regardless of these criticisms, his theory popularized the humanistic movement and led many psychologists to focus on human potential and the positive side of humankind. Carl Rogers, the other major proponent of the humanistic approach, also focused on self-actualization. Unlike Maslow, however, Rogers based his theory upon his clinical work.

Carl Rogers

Michael Rougier/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

Rogers’s self theory. Freud’s psychoanalytic theory of personality led to psychoanalysis, a type of psychotherapy used to help those suffering personality problems. Carl Rogers’s self theory of personality led to another influential style of psychotherapy, client-centered (or person-centered) therapy (Rogers, 1951, 1961), which we will discuss in Chapter 10, on abnormal psychology. It is interesting to note that Rogers was a clinician in an academic setting during most of the time he was developing his theory (Schultz, 2001). His clients were not like those of psychotherapists in the private sector; he mainly dealt with young, bright people with adjustment problems. Keep this in mind as we consider his theory, since his clinical experiences likely guided its development.

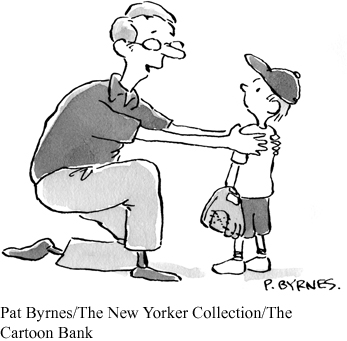

conditions of worth The behaviors and attitudes for which other people, starting with our parents, will give us positive regard.

“Just remember, son, it doesn’t matter whether you win or lose–unless you want Daddy’s love.”

Pat Byrnes/The New Yorker Collection/The Cartoon Bank

Like Maslow, Rogers emphasized self-actualization, the development of one’s fullest potential. He believed that this was the fundamental drive for humans. Sometimes we have difficulty in this actualization process, though, and this is the source of personality problems. How does this happen? Like Freud, Rogers believed that early experience was important, but for very different reasons. He thought that we have a strong need for positive regard—to be accepted by and have the affection of others, especially the significant others in our life. Our parents (or caregivers) set up conditions of worth, the behaviors and attitudes for which they will give us positive regard. Infants and children develop their self-concept in relation to these conditions of worth in order to be liked and accepted by others and feel a sense of self-worth.

unconditional positive regard Unconditional acceptance and approval of a person by others.

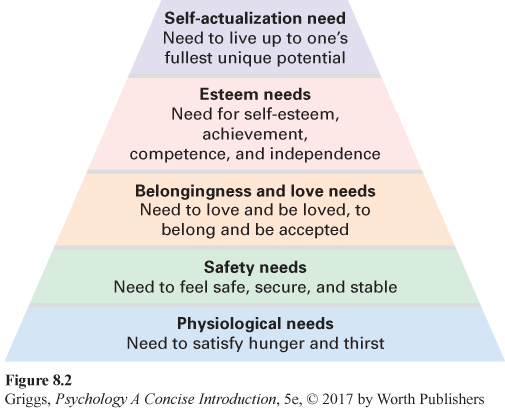

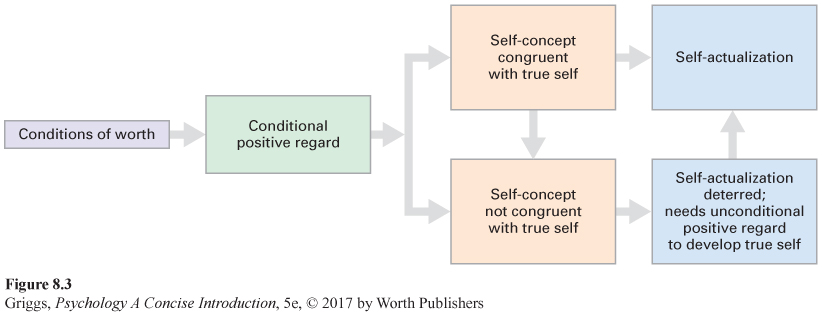

Meeting the conditions of worth continues throughout our lives. We want to be regarded positively by others, so we meet their conditions. There’s a problem, though. In meeting these conditions of worth, we may develop a self-concept of what others think we should be. The problem is that this self-concept might not be the same as our true, ideal self, and thus would deter self-actualization. This conflict is created by conditional positive regard, so Rogers developed the concept of unconditional positive regard—acceptance and approval without conditions. In addition to giving us unconditional positive regard (liking us no matter what we are like), it is important that others be empathetic (able to truly understand our feelings) and genuine with respect to their own feelings if we are to self-actualize. As we will learn in Chapter 10, these characteristics are critical elements in Rogers’s client-centered therapy. Rogers’s self theory is summarized in Figure 8.3.

Figure 8.3: Figure 8.3 | Carl Rogers’s Self Theory | According to Carl Rogers, the development of your self-concept is impacted by the conditions of worth set up by those people who are important to you. Their conditional positive regard may lead you to develop a self-concept that is congruent with your true self, thereby allowing you to self-actualize; or it may lead to a conflict between your developed self-concept and your true self. If there is a conflict, then you will need unconditional positive regard in order to develop your true self and self-actualize.

Rogers’s theory, like Freud’s theory, is based on clinical experience and is important mainly because of its application to therapy. Neither theory is research-based. The social-cognitive approach, which we will discuss next, is research-based. It combines elements of three of the major research perspectives—the cognitive, behavioral, and sociocultural approaches. The social-cognitive approach stresses that personality development involves learning that occurs in a social context and is mediated by cognitive processes. Let’s see how.

The Social-Cognitive Approach to Personality

Social-cognitive theorists agree with behaviorists that learning through environmental conditioning contributes to personality development. However, they think that social learning (modeling) and cognitive processes, such as perception and thinking, are also involved and are actually more important to the development of our personality. To understand how modeling and cognitive processes are involved, we’ll first consider the work of Albert Bandura, one of the main proponents of the social-cognitive approach.

self-system The set of cognitive processes by which a person observes, evaluates, and regulates her behavior.

Bandura’s self-system. Bandura proposed that the behaviors that define one’s personality are a product of a person’s self-system (Bandura, 1973, 1986). This self-system is the set of cognitive processes by which a person observes, evaluates, and regulates her behavior. Social learning illustrates how this system works. Children observe the various behaviors of the models in their social environment, especially those of their parents. Given this observational learning, children may then choose, at some later time, to imitate these behaviors, especially if they were reinforced earlier. If these behaviors continue to be reinforced, children may then incorporate them into their personality. This means that there is self-direction (the child consciously chooses which behaviors to imitate). The child’s behavior is not just automatically elicited by environmental stimuli. People observe and interpret the effects of not only their own behavior, but also the behavior of others. Then they act in accordance with their assessment of whether the behavior will be reinforced or not. We do not respond mechanically to the environment; we choose our behaviors based on our expectations of reinforcement or punishment.

self-efficacy A judgment of one’s effectiveness in dealing with particular situations.

Bandura also proposed that people observe their own behavior and judge its effectiveness relative to their own standards (Bandura, 1997). This self-evaluation process impacts our sense of self-efficacy—a judgment of one’s effectiveness in dealing with particular situations. Success increases our sense of self-efficacy; failure decreases it. According to Bandura, our sense of self-efficacy plays a major role in determining our behavior. People generally low in self-efficacy tend to be depressed and anxious and feel helpless. People generally high in self-efficacy are confident and positive in their outlook and have little self doubt. They also have greater persistence in working to attain goals and usually achieve greater success than those with low self-efficacy. Self-efficacy parallels the story of the little engine that could. To do something, you have to think you can do it.

external locus of control The perception that chance or external forces beyond one’s personal control determine one’s fate.

internal locus of control The perception that one controls one’s own individual fate.

Rotter’s locus of control. Bandura’s self-efficacy concept is similar to locus of control, a concept proposed by another social-cognitive theorist, Julian Rotter. According to Rotter, locus of control refers to a person’s perception of the extent to which he controls what happens to him (Rotter, 1966, 1990). “Locus” means place. There are two major places that control can reside—outside you or within you. External locus of control refers to the perception that chance or external forces beyond your personal control determine your fate. Internal locus of control refers to the perception that you control your own fate. How is locus of control different from self-efficacy? People with an internal locus of control perceive their success as dependent upon their own actions, but they may or may not feel that they have the competence (efficacy) to bring about successful outcomes in various situations. For example, students may think that their own study preparation determines their exam performance, but they may not think that they have satisfactory study skills to produce good exam performance. For those with external locus of control, the self-efficacy concept isn’t as relevant because such people believe that the outcomes of their actions are not affected by their actions.

learned helplessness A sense of hopelessness in which a person thinks that he is unable to prevent aversive events.

Why is Rotter’s locus of control concept important? Research has shown that people with an internal locus of control are psychologically and physically better off. They are more successful in school, healthier, and better able to cope with the stresses of life (Lachman & Weaver, 1998). In addition, an external locus of control may contribute to learned helplessness, a sense of hopelessness in which individuals think that they are unable to prevent unpleasant events (Seligman, 1975). But how does this happen? What goes on in the minds of those who become helpless? To understand, we first need to consider self-perception and the attribution process.

attribution The process by which we explain our own behavior and that of others.

Self-perception. Given the impact of self-efficacy and locus of control, positive self-perception is important to healthy behavior. Our behavior, however, does not always lead to good outcomes. How, then, do we deal with poor outcomes and maintain positive self-perception? To understand how we do so, we need to understand attribution, the process by which we explain our own behavior and that of others. There are two types of attributions, internal and external. An internal attribution means that the outcome is attributed to the person. An external attribution means that the outcome is attributed to factors outside the person. Let’s consider an example. You fail a psychology exam. Why? An internal attribution gives you the blame. For example, you might say, “I just didn’t study enough.” An external attribution would place the blame elsewhere. For example, you might say, “I knew the material, but that exam was unfair.” In this case, you tend to make an external attribution. Why?

self-serving bias The tendency to make attributions so that one can perceive oneself favorably.

We place the blame elsewhere in order to protect our self-esteem. This attribution bias is called the self-serving bias, the tendency to make attributions so that one can perceive oneself favorably. If the outcome of our behavior is positive, we take credit for it (make an internal attribution). However, if the outcome is negative, we place the blame elsewhere (make an external attribution). The research evidence indicating that we use the self-serving bias is overwhelming (Myers, 2013). Think about it. Don’t most of us think that we are above average in intelligence, attractiveness, and other positive characteristics? But most people can’t be above average, can they? These self-enhancing perceptions created by the self-serving bias serve to maintain our self-esteem. This bias is adaptive because it protects us from falling prey to learned helplessness and depression. When negative events happen, we don’t blame ourselves. Instead, we make external attributions and place the blame elsewhere.

So what type of explanatory style might lead us toward learned helplessness and depression? A pessimistic explanatory style is one answer (Peterson, Maier, & Seligman, 1993). First, the attributions of people using a pessimistic explanatory style tend to show a pattern that is the opposite of those generated by self-serving bias. Negative outcomes are given internal explanations (“I don’t have any ability”), and positive outcomes external explanations (“I just got lucky”). There is more to it, however. Pessimistic explanations also tend to be stable (the person thinks that the outcome causes are permanent) and global (the causes affect most situations). Think about a person using a pessimistic explanatory style when experiencing a series of negative events. Not only would such a person blame himself (internal), but he would also think that such negative events would continue (stable) and impact most aspects of his life (global). Such thinking could easily lead to the perception of an external locus of control and learned helplessness followed by depression. Indeed, much research has supported the relationship between styles of attribution, helplessness, and depression (Peterson & Seligman, 1984; Rotenberg, Costa, Trueman, & Lattimore, 2012; Seligman et al., 1988). In addition, uncontrollable negative events have been found to lead to lower serotonin and norepinephrine activity in rats (Wu et al., 1999), the activity pattern observed for these neurotransmitters in the brains of people diagnosed with depression.

Section Summary

The humanistic approach to the study of personality developed as part of the humanistic movement in the 1960s in response to the rather deterministic psychoanalytic and behavioral approaches that dominated psychology at that time. In contrast to these two approaches, the humanistic theorists emphasized conscious free will in one’s development and the importance of self-actualization, the fullest realization of our potential, as a major motivator of our behavior. Based on his studies of very healthy and creative people, humanistic theorist Abraham Maslow developed a hierarchy of needs that motivate our behavior and development. From bottom to top, the needs are physiological, safety, belonging and love, esteem, and self-actualization. Motivation proceeds from the bottom of the hierarchy to the top, because a person cannot work toward self-actualization until the lower-level needs are met. Carl Rogers, the other major humanistic theorist, also focused on self-actualization as a major human motivation. According to Rogers, for a person to be self-actualized, the people in that person’s life must set up conditions of worth that lead the person’s developed self-concept to match her true self or they must give unconditional positive regard—acceptance and approval without conditions—which will allow the person to develop into her true self.

The social-cognitive approach to personality arose out of disenchantment with the rather narrow strict behavioral approach. Social-cognitive theorists agree that learning through conditioning is important, but that social learning (modeling) and cognitive processes are more important to the development of personality. For example, Albert Bandura proposed a self-system, a set of cognitive processes by which a person observes, evaluates, and regulates her behavior. Our sense of self-efficacy (our evaluation of our effectiveness in particular situations) is a key element in Bandura’s theory for maintaining a healthy personality.

Julian Rotter’s locus of control concept also demonstrates the importance of cognitive processing to psychological health. An external locus of control is the perception that chance or external forces beyond our personal control determine our fate. An internal locus of control is the perception that we control our own fate. People with an internal locus of control do better in school, are healthier, and are better able to cope with the stresses of life. To maintain positive self-evaluation, we also use self-serving bias in our explanations of our behavior. If the outcome of our behavior is positive, we take credit for it; if it is not, we do not. This bias is adaptive and protects us from depression. In contrast, a pessimistic explanatory style—in which we take the blame for negative outcomes and not positive ones, and see these outcomes as both stable and global—is maladaptive and will likely lead to feelings of learned helplessness and depression.

2

Question

8.4

Explain which needs, according to Maslow, must be satisfied before a person can worry about self-actualization.

In Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, physiological, safety, belonging and love, and esteem needs have to be satisfied before the highest level need for self-actualization can be met.

Question

8.5

Explain why, according to Rogers’s self theory, unconditional positive regard is important.

Positive regard for a person should be unconditional so that the person is free to develop her true self and thus work toward self-actualization. If our positive regard for a person is conditionalized (we set up conditions of worth for that person), then the person develops a self-concept of what others think she should be. This self may be very different from the person’s true self and thus prevent self-actualization.

Question

8.6

Explain how the social-cognitive concepts of self-efficacy and locus of control are similar.

Both self-efficacy and locus of control are cognitive judgments about our effectiveness in dealing with the situations that occur in our lives. Whereas self-efficacy is a person’s judgment of his effectiveness in dealing with particular situations, locus of control is a more global judgment of how much a person controls what happens to him. Both a low general sense of self-efficacy and an external locus of control (i.e., the perception that forces beyond one’s control determine one’s fate) often lead to depression.