“Tippecanoe and Tyler Too!”

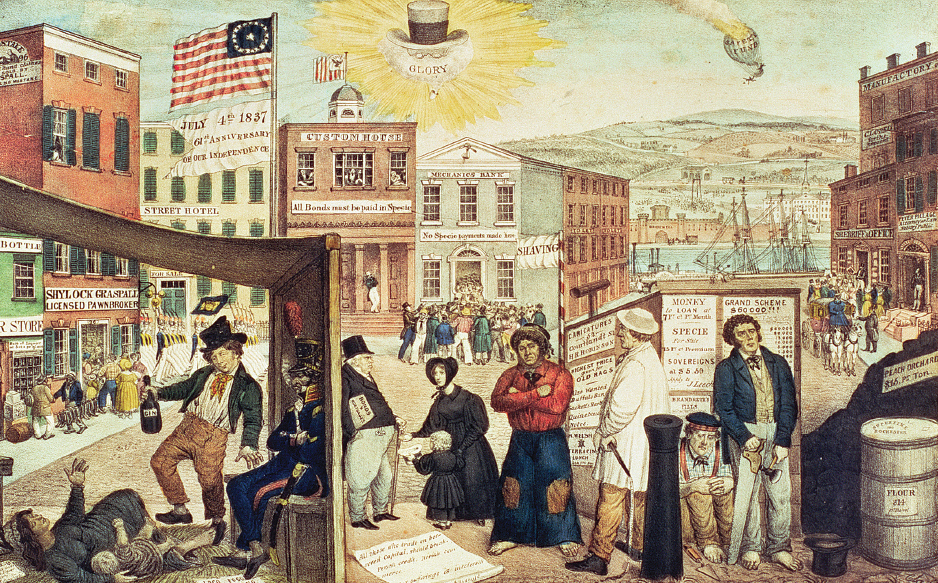

Many Americans blamed the Democrats for the depression of 1837–1843. They criticized Jackson for destroying the Second Bank and directing the Treasury Department in 1836 to issue the Specie Circular, an executive order that required the Treasury Department to accept only gold and silver in payment for lands in the national domain. Critics charged — mistakenly — that the Circular drained so much specie from the economy that it sparked the Panic of 1837. In fact (as noted above), the curtailing of credit by the Bank of England was the main cause of the panic.

Nonetheless, the public turned its anger on Van Buren, who took office just before the panic struck. Ignoring the pleas of influential bankers, the new president refused to revoke the Specie Circular or take actions to stimulate the economy. Holding to his philosophy of limited government, Van Buren advised Congress that “the less government interferes with private pursuits the better for the general prosperity.” As the depression deepened in 1839, this laissez-faire outlook commanded less and less political support. Worse, Van Buren’s major piece of fiscal legislation, the Independent Treasury Act of 1840, delayed recovery by pulling federal specie out of Jackson’s pet banks (where it had backed loans) and placing it in government vaults, where it had little economic impact.

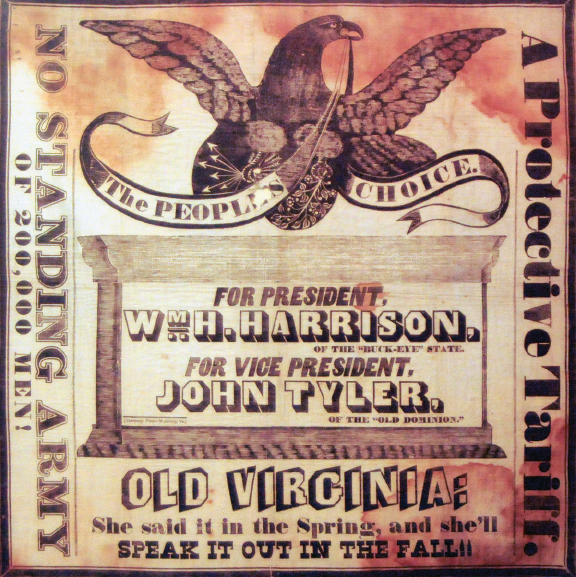

The Log Cabin Campaign The Whigs exploited Van Buren’s weakness. In 1840, they organized their first national convention and nominated William Henry Harrison of Ohio for president and John Tyler of Virginia for vice president. A military hero of the Battle of Tippecanoe and the War of 1812, Harrison was well advanced in age (sixty-eight) and had little political experience. However, the Whig leaders in Congress, Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, wanted a president who would rubber-stamp their program for protective tariffs and a national bank. An unpretentious, amiable man, Harrison told voters that Whig policies were “the only means, under Heaven, by which a poor industrious man may become a rich man without bowing to colossal wealth.”

The depression stacked the political cards against Van Buren, but the election turned as much on style as on substance. It became the great “log cabin campaign” — the first time two well-organized parties competed for votes through a new style of campaigning. Whig songfests, parades, and well-orchestrated mass meetings drew new voters into politics. Whig speakers assailed “Martin Van Ruin” as a manipulative politician with aristocratic tastes — a devotee of fancy wines, elegant clothes, and polite refinement, as indeed he was. Less truthfully, they portrayed Harrison as a self-made man who lived contentedly in a log cabin and quaffed hard cider, a drink of the common people. In fact, Harrison’s father was a wealthy Virginia planter who had signed the Declaration of Independence, and Harrison himself lived in a series of elegant mansions.

The Whigs boosted their electoral hopes by welcoming women to campaign festivities — a “first” for American politics. Many Jacksonian Democrats had long embraced an ideology of aggressive manhood, likening politically minded females to “public” women, prostitutes who plied their trade in theaters and other public places. Whigs took a more restrained view of masculinity and recognized that Christian women had already entered American public life through the temperance movement and other benevolent activities. In October 1840, Daniel Webster celebrated moral reform to an audience of twelve hundred women and urged them to back Whig candidates. “This way of making politicians of their women is something new under the sun,” exclaimed one Democrat, worried that it would bring more Whig men to the polls. And it did: more than 80 percent of the eligible male voters cast ballots in 1840, up from fewer than 60 percent in 1832 and 1836 (see Figure 10.1). Heeding the Whigs’ campaign slogan “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too,” they voted Harrison into the White House with 53 percent of the popular vote and gave the party a majority in Congress.

Tyler Subverts the Whig Agenda Led by Clay and Webster, the Whigs in Congress prepared to reverse the Jacksonian revolution. Their hopes were short-lived; barely a month after his inauguration in 1841, Harrison died of pneumonia, and the nation got “Tyler Too.” But in what capacity: as acting president or as president? The Constitution was vague on the issue. Ignoring his Whig associates in Congress, who wanted a weak chief executive, Tyler took the presidential oath of office and declared his intention to govern as he pleased. As it turned out, that would not be like a Whig.

Tyler had served in the House and the Senate as a Jeffersonian Democrat, firmly committed to slavery and states’ rights. He had joined the Whigs only to protest Jackson’s stance against nullification. On economic issues, Tyler shared Jackson’s hostility to the Second Bank and the American System. He therefore vetoed Whig bills that would have raised tariffs and created a new national bank. Outraged by this betrayal, most of Tyler’s cabinet resigned in 1842, and the Whigs expelled Tyler from their party. “His Accidency,” as he was called by his critics, was now a president without a party.

The split between Tyler and the Whigs allowed the Democrats to regroup. The party vigorously recruited subsistence farmers in the North, smallholding planters in the South, and former members of the Working Men’s Parties in the cities. It also won support among Irish and German Catholic immigrants — whose numbers had increased during the 1830s — by backing their demands for religious and cultural liberty, such as the freedom to drink beer and whiskey. A pattern of ethnocultural politics, as historians refer to the practice of voting along ethnic and religious lines, now became a prominent feature of American life. Thanks to these urban and rural recruits, the Democrats remained the majority party in most parts of the nation. Their program of equal rights, states’ rights, and cultural liberty was attractive to more white Americans than the Whig platform of economic nationalism, moral reform, temperance laws, and individual mobility.

UNDERSTAND POINTS OF VIEW