Joseph Smith and the Mormon Experience

The Mormons, members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, were religious utopians with a conservative social agenda: to perpetuate close-knit communities and patriarchal power. Because of their cohesiveness, authoritarian leadership, and size, the Mormons provoked more animosity than the radical utopians did.

Joseph Smith Like many social movements of the era, Mormonism emerged from religious ferment among families of Puritan descent who lived along the Erie Canal and who were heirs to a religious tradition that believed in a world of wonders, supernatural powers, and visions of the divine.

The founder of the Latter-day Church, Joseph Smith Jr. (1805–1844), was born in Vermont to a poor farming and shop-keeping family that migrated to Palmyra in central New York. In 1820, Smith began to have religious experiences similar to those described in conversion narratives: “[A] pillar of light above the brightness of the sun at noonday came down from above and rested upon me and I was filled with the spirit of God.” Smith came to believe that God had singled him out to receive a special revelation of divine truth. In 1830, he published The Book of Mormon, which he claimed to have translated from ancient hieroglyphics on gold plates shown to him by an angel named Moroni. The Book of Mormon told the story of an ancient Jewish civilization from the Middle East that had migrated to the Western Hemisphere and of the visit of Jesus Christ, soon after his Resurrection, to those descendants of Israel. Smith’s account explained the presence of native peoples in the Americas and integrated them into the Judeo-Christian tradition.

Smith proceeded to organize the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Seeing himself as a prophet in a sinful, excessively individualistic society, Smith revived traditional social doctrines, including patriarchal authority. Like many Protestant ministers, he encouraged practices that led to individual success in the age of capitalist markets and factories: frugality, hard work, and enterprise. Smith also stressed communal discipline to safeguard the Mormon “New Jerusalem.” His goal was a church-directed society that would restore primitive Christianity and encourage moral perfection.

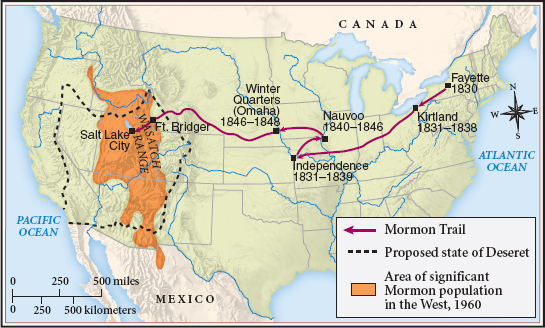

Constantly harassed by anti-Mormons, Smith struggled to find a secure home for his new religion. At one point, he identified Jackson County in Missouri as the site of the sacred “City of Zion,” and his followers began to settle there. Agitation led by Protestant ministers quickly forced them out: “Mormons were the common enemies of mankind and ought to be destroyed,” said one cleric. Smith and his growing congregation eventually settled in Nauvoo, Illinois, a town they founded on the Mississippi River (Map 11.2). By the early 1840s, Nauvoo had 30,000 residents. The Mormons’ rigid discipline and secret rituals — along with their prosperity, hostility toward other sects, and bloc voting in Illinois elections — fueled resentment among their neighbors. That resentment increased when Smith refused to accept Illinois laws of which he disapproved, asked Congress to make Nauvoo a separate federal territory, and declared himself a candidate for president of the United States.

Moreover, Smith claimed to have received a new revelation justifying polygamy, the practice of a man having multiple wives. When leading Mormon men took several wives — “plural celestial marriage” — they threw the Mormon community into turmoil and enraged nearby Christians. In 1844, Illinois officials arrested Smith and charged him with treason for allegedly conspiring to create a Mormon colony in Mexican territory. An anti-Mormon mob stormed the jail in Carthage, Illinois, where Smith and his brother were being held and murdered them.

Brigham Young and Utah Led by Brigham Young, Smith’s leading disciple and now the sect’s “prophet, seer and revelator,” about 6,500 Mormons fled the United States. Beginning in 1846, they crossed the Great Plains into Mexican territory and settled in the Great Salt Lake Valley in present-day Utah. Using cooperative labor and an irrigation system based on communal water rights, the Mormon pioneers quickly spread agricultural communities along the base of the Wasatch Range. Many Mormons who rejected polygamy remained in the United States. Led by Smith’s son, Joseph Smith III, they formed the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and settled throughout the Midwest.

When the United States acquired Mexico’s northern territories in 1848, the Salt Lake Mormons petitioned Congress to create a vast new state, Deseret, stretching from Utah to the Pacific coast. Instead, Congress set up the much smaller Utah Territory in 1850 and named Brigham Young its governor. Young and his associates ruled in an authoritarian fashion, determined to ensure the ascendancy of the Mormon Church and its practices. By 1856, Young and the Utah territorial legislature were openly vowing to resist federal laws. Pressed by Protestant church leaders to end polygamy and considering the Mormons’ threat of nullification “a declaration of war,” President James Buchanan dispatched a small army to Utah. As the “Nauvoo Legion” resisted the army’s advance, aggressive Mormon militia massacred a party of 120 California-bound emigrants and murdered suspicious travelers and Mormons seeking to flee Young’s regime. Despite this bloodshed, the “Mormon War” ended quietly in June 1858. President Buchanan, a longtime supporter of the white South, feared that the forced abolition of polygamy would serve as a precedent for ending slavery and offered a pardon to Utah citizens who would acknowledge federal authority. (To enable Utah to win admission to the Union in 1896, its citizens ratified a constitution that “forever” banned the practice of polygamy. However, the state government has never strictly enforced that ban.)

The Salt Lake Mormons had succeeded even as other social experiments had failed. Reaffirming traditional values, their leaders resolutely used strict religious controls to perpetuate patriarchy and communal discipline. However, by endorsing private property and individual enterprise, Mormons became prosperous contributors to the new market society. This blend of economic innovation, social conservatism, and hierarchical leadership, in combination with a strong missionary impulse, created a wealthy and expansive church that now claims a worldwide membership of about 12 million people.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST