Negotiating Rights

By forming stable families and communities, African Americans gradually created a sense of order in the harsh and arbitrary world of slavery. In a few regions, slaves won substantial control over their lives.

Working Lives During the Revolutionary era, blacks in the rice-growing lowlands of South Carolina successfully asserted the right to labor by the “task.” Under the task system, workers had to complete a precisely defined job each day — for example, digging up a quarter-acre of land, hoeing half an acre, or pounding seven mortars of rice. By working hard, many finished their tasks by early afternoon, a Methodist preacher reported, and had “the rest of the day for themselves, which they spend in working their own private fields … planting rice, corn, potatoes, tobacco &c. for their own use and profit.”

Slaves on sugar and cotton plantations led more regimented lives, thanks to the gang-labor system. As one field hand put it, there was “no time off [between] de change of de seasons. …Dey was allus clearin’ mo’ lan’ or sump’. ” Many slaves faced bans on growing crops on their own. “It gives an excuse for trading,” explained one owner, and that encouraged roaming and independence. Still, many masters hired out surplus workers as teamsters, drovers, steamboat workers, turpentine gatherers, and railroad builders; in 1856, no fewer than 435 hired slaves laid track for the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad. Many owners regretted the result. As an overseer remarked about a slave named John, “He is not as good a hand as he was before he went to Alabamy.”

The planters’ greatest fear was that enslaved African Americans — a majority of the population in most cotton-growing counties — would rise in rebellion. Legally speaking, owners had virtually unlimited power over their slaves. “The power of the master must be absolute,” intoned Justice Thomas Ruffin of the North Carolina Supreme Court in 1829. But absolute power required brutal coercion, and only hardened or sadistic masters had the stomach for such violence. “These poor negroes, receiving none of the fruits of their labor, do not love work,” explained one woman who worked her own farm; “if we had slaves, we should have to …beat them to make use of them.”

Moreover, passive resistance by African Americans seriously limited their owners’ power. Slaves slowed the pace of work by feigning illness and losing or breaking tools. One Maryland slave, faced with transport to Mississippi and separation from his wife, flatly refused “to accompany my people, or to be exchanged or sold,” his owner reported. Masters ignored such feelings at their peril. A slave (or a relative) might retaliate by setting fire to the master’s house and barns, poisoning his food, or destroying his crops. Fear of resistance, as well as critical scrutiny by abolitionists, prompted many masters to reduce their reliance on the lash and use positive incentives such as food and special privileges. Noted Frederick Law Olmsted: “Men of sense have discovered that it was better to offer them rewards than to whip them.” Nonetheless, owners could always resort to violence, and countless masters regularly asserted their power by demanding sex from their female slaves. As ex-slave Bethany Veney lamented in her autobiography, from “the unbridled lust of the slave-owner… the law holds …no protecting arm” over black women.

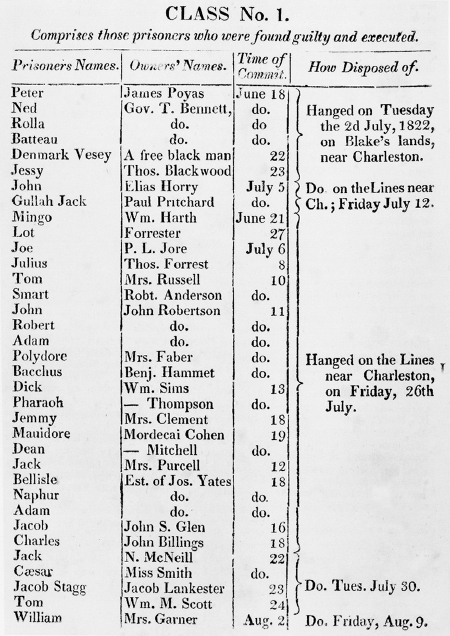

Survival Strategies Slavery remained an exploitative system grounded in fear and coercion. Over the decades, hundreds of individual slaves responded by attacking their masters and overseers. But only a few blacks — among them Gabriel and Martin Prosser (1800) and Nat Turner (1831) — plotted mass uprisings. Most slaves recognized that revolt would be futile; they lacked the autonomous institutions such as the communes of European peasants, for example, needed to organize a successful rebellion. Moreover, whites were numerous, well armed, and determined to maintain their position of racial superiority.

Escape was equally problematic. Blacks in the Upper South could flee to the North, but only by leaving their family and kin. Slaves in the Lower South escaped to sparsely settled regions of Florida, where some intermarried with the Seminole Indians. Elsewhere in the South, escaped slaves eked out a meager existence in inhospitable marshy areas or mountain valleys. Consequently, most African Americans remained on plantations; as Frederick Douglass put it, they were “pegged down to one single spot, and must take root there or die.”

“Taking root” meant building the best possible lives for themselves. Over time, enslaved African Americans pressed their owners for a greater share of the product of their labor, much like unionized workers in the North were doing. Thus slaves insisted on getting paid for “overwork” and on the right to cultivate a garden and sell its produce. “De menfolks tend to de gardens round dey own house,” recalled a Louisiana slave. “Dey raise some cotton and sell it to massa and git li’l money dat way.” Enslaved women raised poultry and sold chickens and eggs. An Alabama slave remembered buying “Sunday clothes with dat money, sech as hats and pants and shoes and dresses.” By the 1850s, thousands of African Americans were reaping the small rewards of this underground economy, and some accumulated sizable property. Enslaved Georgia carpenter Alexander Steele owned four horses, a mule, a silver watch, two cows, a wagon, and large quantities of fodder, hay, and corn.

Whatever their material circumstances, few slaves accepted the legitimacy of their status. Although he was fed well and never whipped, a former slave told an English traveler, “I was cruelly treated because I was kept in slavery.”

PLACE EVENTS IN CONTEXT