The Upper South Exports Slaves

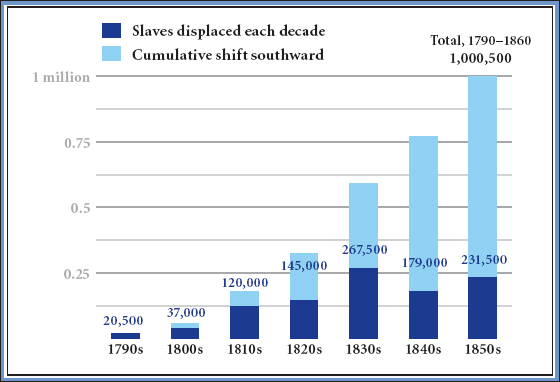

Planters seeking labor looked to the Chesapeake region, home in 1800 to nearly half of the nation’s black population. There, the African American population was growing rapidly from natural increase — an average of 27 percent a decade by the 1810s — and creating a surplus of enslaved workers on many plantations. The result was a growing domestic trade in slaves. Between 1818 and 1829, planters in just one Maryland tobacco-growing county — Frederick — sold at least 952 slaves to traders or cotton planters. Plantation owners in Virginia disposed of 75,000 slaves during the 1810s and again during the 1820s. The number of forced Virginia migrants jumped to nearly 120,000 during the 1830s and then averaged 85,000 during the 1840s and 1850s. In Virginia alone, then, slave owners ripped 440,000 African Americans from communities where their families had lived for three or four generations. By 1860, the “mania for buying negroes” from the Upper South had resulted in a massive transplantation of more than 1 million slaves (Figure 12.2). A majority of African Americans now lived and worked in the Deep South, the lands that stretched from Georgia to Texas.

This African American migration took two forms: transfer and sale. Looking for new opportunities, thousands of Chesapeake and Carolina planters — men like James Lide — sold their existing plantations and moved their slaves to the Southwest. Many other planters gave slaves to sons and daughters who moved west. Such transfers accounted for about 40 percent of the African American migrants. The rest — about 60 percent of the 1 million migrants — were “sold south” through traders.

Just as the Atlantic slave trade enriched English merchants in the eighteenth century, so the domestic market brought wealth to American traders between 1800 and 1860. One set of routes ran to the Atlantic coast and sent thousands of slaves to sugar plantations in Louisiana, the former French territory that entered the Union in 1812. As sugar output soared, slave traders scoured the countryside near the port cities of Baltimore, Alexandria, Richmond, and Charleston — searching, as one of them put it, for “likely young men such as I think would suit the New Orleans market.” Each year, hundreds of muscular young slaves passed through auction houses in the port cities bound for the massive trade mart in New Orleans. Because this coastal trade in laborers was highly visible, it elicited widespread condemnation by northern abolitionists.

Sugar was a “killer” crop, and Louisiana (like the eighteenth-century West Indies) soon had a well-deserved reputation among African Americans “as a place of slaughter.” Hundreds died each year from disease, overwork, and brutal treatment. Maryland farmer John Anthony Munnikhuysen refused to allow his daughter Priscilla to marry a Louisiana sugar planter, declaring: “Mit has never been used to see negroes flayed alive and it would kill her.”

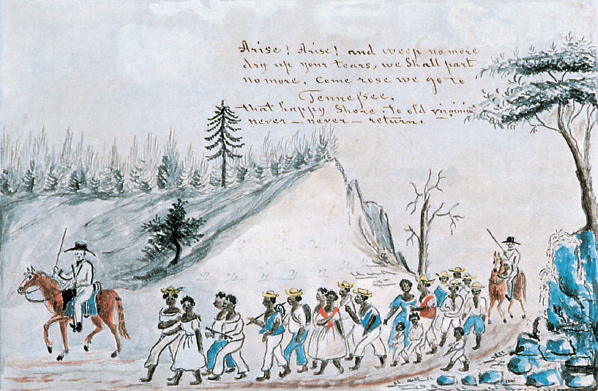

The inland system that fed slaves to the Cotton South was less visible than the coastal trade but more extensive. Professional slave traders went from one rural village to another buying “young and likely Negroes.” The traders marched their purchases in coffles — columns of slaves bound to one another — to Alabama, Mississippi, and Missouri in the 1830s and to Arkansas and Texas in the 1850s. One slave described the arduous journey: “Dem Speckulators would put the chilluns in a wagon usually pulled by oxens and de older folks was chained or tied together sos dey could not run off.” Once a coffle reached its destination, the trader would sell slaves “at every village in the county.”

Chesapeake and Carolina planters provided the human cargo. Some planters sold slaves when poor management or their “own extravagances” threw them into debt. “Trouble gathers thicker and thicker around me,” Thomas B. Chaplin of South Carolina lamented in his diary. “I will be compelled to send about ten prime Negroes to Town on next Monday, to be sold.” Many more planters doubled as slave traders, earning substantial profits by traveling south to sell some of their slaves and those of their neighbors. Thomas Weatherly of South Carolina drove his surplus slaves to Hayneville, Alabama, where he “sold ten negroes.” Colonel E. S. Irvine, a member of the South Carolina legislature and “a highly respected gentleman” in white circles, likewise traveled frequently “to sell a drove of Negroes.” Prices marched in step with those for cotton; during a boom year in the 1850s, a planter noted that a slave “will fetch $1000, cash, quick.”

The domestic slave trade was crucial to the prosperity of the migrating white planters because it provided workers to fell the forests and plant cotton in the Gulf states. Equally important, it sustained the wealth of slave owners in the Upper South. By selling surplus black workers, tobacco, rice, and grain producers in the Chesapeake and Carolinas added about 20 percent to their income. As a Maryland newspaper remarked in 1858, “[The trade serves as] an almost universal resource to raise money. A prime able-bodied slave is worth three times as much to the cotton or sugar planter as to the Maryland agriculturalist.”

IDENTIFY CAUSES