The Impact on Blacks

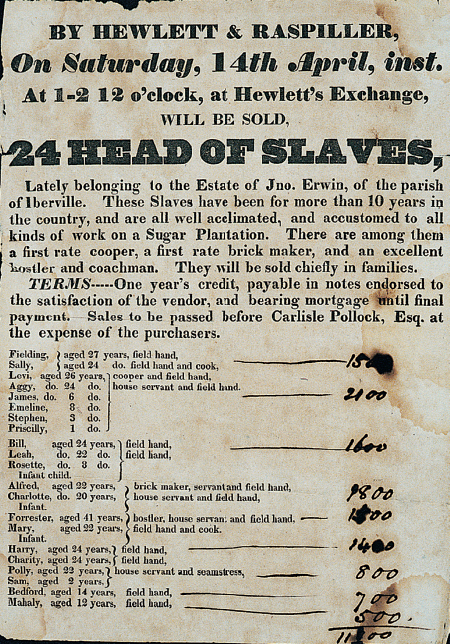

For African American families, the domestic slave trade was a personal disaster that underlined their status — and vulnerability — as chattel slaves. In law, they were the movable personal property of the whites who owned them. As Lewis Clark, a fugitive from slavery, noted: “Many a time i’ve had ’em say to me, ‘You’re my property.’” “The being of slavery, its soul and its body, lives and moves in the chattel principle, the property principle, the bill of sale principle,” declared former slave James W. C. Pennington. As a South Carolina master put it, “[The slave’s earnings] belong to me because I bought him.”

Slave property underpinned the entire southern economic system. Whig politician Henry Clay noted that the “immense amount of capital which is invested in slave property … is owned by widows and orphans, by the aged and infirm, as well as the sound and vigorous. It is the subject of mortgages, deeds of trust, and family settlements.” Clay concluded: “I know that there is a visionary dogma, which holds that negro slaves cannot be the subject of property [but] …that is property which the law declares to be property.”

As a slave owner, Clay also knew that property rights were key to slave discipline. “I govern them… without the whip,” another master explained, “by stating …that I should sell them if they do not conduct themselves as I wish.” The threat was effective. “The Negroes here dread nothing on earth so much as this,” a Maryland observer noted. “They regard the south with perfect horror, and to be sent there is considered as the worst punishment.” Thousands of slaves suffered that fate, which destroyed about one in every four slave marriages. “Why does the slave ever love?” asked black abolitionist Harriet Jacobs in her autobiography, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, when her partner “may at any moment be wrenched away by the hand of violence?” After being sold, one Georgia slave lamented, “My Dear wife for you and my Children my pen cannot Express the griffe I feel to be parted from you all.”

The interstate slave trade often focused on young adults. In northern Maryland, planters sold away boys and girls at an average age of seventeen years. “Dey sole my sister Kate,” Anna Harris remembered decades later, “and I ain’t seed or heard of her since.” The trade also separated almost a third of all slave children under the age of fourteen from one or both of their parents. Sarah Grant remembered, “Mamma used to cry when she had to go back to work because she was always scared some of us kids would be sold while she was away.” Well might she worry, for slave traders worked quickly. “One night I lay down on de straw mattress wid my mammy,” Vinny Baker recalled, “an’ de nex’ mo’nin I woke up an’ she wuz gone.” When their owner sold seven-year-old Laura Clark and ten other children from their plantation in North Carolina, Clark sensed that she would see her mother “no mo’ in dis life.”

Despite these sales, 75 percent of slave marriages remained unbroken, and the majority of children lived with one or both parents until puberty. Consequently, the sense of family among African Americans remained strong. Sold from Virginia to Texas in 1843, Hawkins Wilson carried with him a mental picture of his family. Twenty-five years later and now a freedman, Wilson set out to find his “dearest relatives” in Virginia. “My sister belonged to Peter Coleman in Caroline County and her name was Jane. …She had three children, Robert, Charles and Julia, when I left — Sister Martha belonged to Dr. Jefferson. …Sister Matilda belonged to Mrs. Botts.”

During the decades between sale and freedom, Hawkins Wilson and thousands of other African Americans constructed new lives for themselves in the Mississippi Valley. Undoubtedly, many did so with a sense of foreboding, knowing from personal experience that their owners could disrupt their lives at any moment. Like Charles Ball, some “longed to die, and escape from the bonds of my tormentors.” The darkness of slavery shadowed even moments of joy. Knowing that sales often ended slave marriages, a white minister blessed one couple “for so long as God keeps them together.”

Many white planters “saw” only the African American marriages that endured and ignored those they had broken. Accordingly, many owners considered themselves benevolent masters, committed to the welfare of “my family, black and white.” Some masters gave substance to this paternalist ideal by treating kindly “loyal and worthy” slaves — black overseers, the mammy who raised their children, and trusted house servants. By preserving the families of these slaves, many planters could believe that they “sold south” only “coarse” troublemakers and uncivilized slaves who had “little sense of family.” Other owners were more honest about the human cost of their pursuit of wealth. “Tomorrow the negroes are to get off [to Kentucky],” a slave-owning woman in Virginia wrote to a friend, “and I expect there will be great crying and moaning, with children Leaving there mothers, mothers there children, and women there husbands.”

Whether or not they acknowledged the slaves’ pain, few southern whites questioned the morality of the slave trade. Responding to abolitionists’ criticism, the city council of Charleston, South Carolina, declared that “the removal of slaves from place to place, and their transfer from master to master, by gift, purchase, or otherwise” was completely consistent “with moral principle and with the highest order of civilization” (American Voices).

|

To see a longer excerpt of the city council of Charleston, South Carolina, document, along with other primary sources from this period, see Sources for America’s History. |

EXPLAIN CONSEQUENCES