Vicksburg and Gettysburg

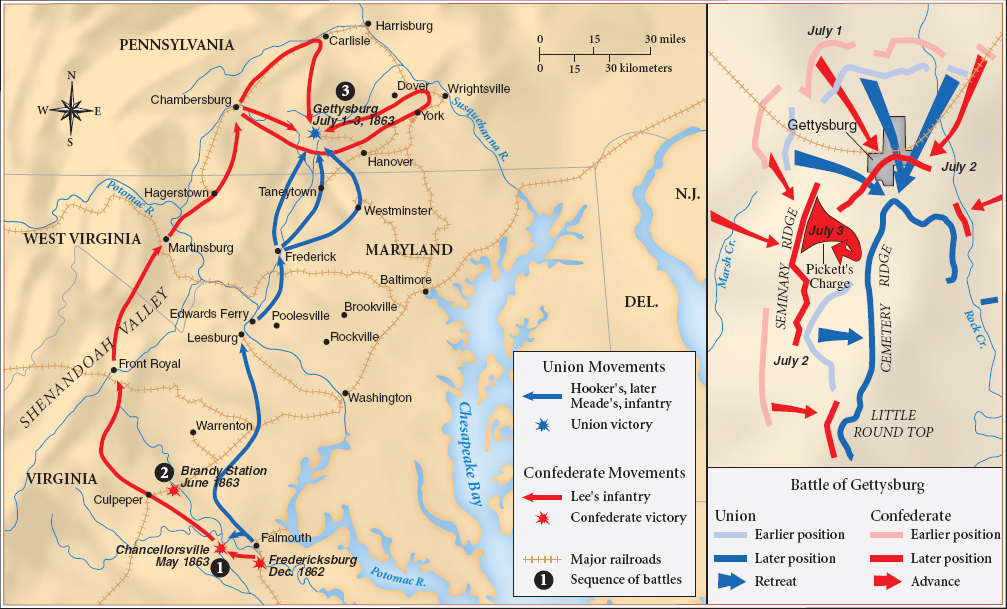

The Emancipation Proclamation’s fate would depend on Republican political success and Union military victories, neither of which looked likely. Democrats had made significant gains in 1862, and popular support was growing for a negotiated peace. Two brilliant victories in Virginia by General Robert E. Lee, whose army defeated Union forces at Fredericksburg (December 1862) and Chancellorsville (May 1863), further eroded northern support for the war.

The Battle for the Mississippi At this critical juncture, General Grant mounted a major offensive to split the Confederacy in two. Grant drove south along the west bank of the Mississippi in Arkansas and then crossed the river near Vicksburg, Mississippi. There, he defeated two Confederate armies and laid siege to the city. After repelling Union assaults for six weeks, the exhausted and starving Vicksburg garrison surrendered on July 4, 1863. Five days later, Union forces took Port Hudson, Louisiana (near Baton Rouge), and seized control of the entire Mississippi River. Grant had taken 31,000 prisoners; cut off Louisiana, Arkansas, and Texas from the rest of the Confederacy; and prompted thousands of slaves to desert their plantations. Confederate troops responded by targeting refugees for re-enslavement and massacre. “The battlefield was sickening,” a Confederate officer reported from Arkansas, “no orders, threats or commands could restrain the men from vengeance on the negroes, and they were piled in great heaps about the wagons, in the tangled brushwood, and upon the muddy and trampled road.”

As Grant had advanced toward Vicksburg in May, Confederate leaders had argued over the best strategic response. President Davis and other politicians wanted to send an army to Tennessee to relieve the Union pressure along the Mississippi River. General Lee, buoyed by his recent victories, favored a new invasion of the North. That strategy, Lee suggested, would either draw Grant’s forces to the east or give the Confederacy a major victory that would destroy the North’s will to fight.

Lee’s Advance and Defeat Lee won out. In June 1863, he maneuvered his army north through Maryland into Pennsylvania. The Army of the Potomac moved along with him, positioning itself between Lee and Washington, D.C. On July 1, the two great armies met by accident at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, in what became a decisive confrontation (Map 14.4). On the first day of battle, Lee drove the Union’s advance guard to the south of town. There, Union commander George G. Meade placed his troops in well-defended hilltop positions and called up reinforcements. By the morning of July 2, Meade had 90,000 troops to Lee’s 75,000. Lee knew he was outnumbered but was intent on victory; he ordered assaults on Meade’s flanks but failed to turn them.

On July 3, Lee decided on a dangerous frontal assault against the center of the Union line. After the heaviest artillery barrage of the war, Lee sent General George E. Pickett and his 14,000 men to take Cemetery Ridge. When Pickett’s men charged across a mile of open terrain, they faced deadly fire from artillery and massed riflemen; thousands suffered death, wounds, or capture. As the three-day battle ended, the Confederates counted 28,000 casualties, one-third of the Army of Northern Virginia, while 23,000 of Meade’s soldiers lay killed or wounded. Shocked by the bloodletting, Meade allowed the Confederate units to escape. Lincoln was furious at Meade’s caution, perceiving that “the war will be prolonged indefinitely.”

Still, Gettysburg was a great Union victory and, together with the simultaneous triumph at Vicksburg, marked a major military, political, and diplomatic turning point. As southern citizens grew increasingly critical of their government, the Confederate elections of 1863 went sharply against the politicians who supported Jefferson Davis. Meanwhile, northern citizens rallied to the Union, and Republicans swept state elections in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and New York. In Europe, the victories boosted the leverage of American diplomats. Since 1862, the British-built ironclad cruiser the Alabama had sunk or captured more than a hundred Union merchant ships, and the Confederacy was about to accept delivery of two more ironclads. With a Union victory increasingly likely, the British government decided to impound the warships and, subsequently, to pay $15.5 million for the depredations of the Alabama. British workers and reformers had long condemned slavery and praised emancipation; moreover, because of poor grain harvests, Britain depended on imports of wheat and flour from the American Midwest. King Cotton diplomacy had failed and King Wheat stood triumphant. “Rest not your hopes in foreign nations,” President Jefferson Davis advised his people. “This war is ours; we must fight it ourselves.”

EXPLAIN CONSEQUENCES