Introduction for Chapter 15

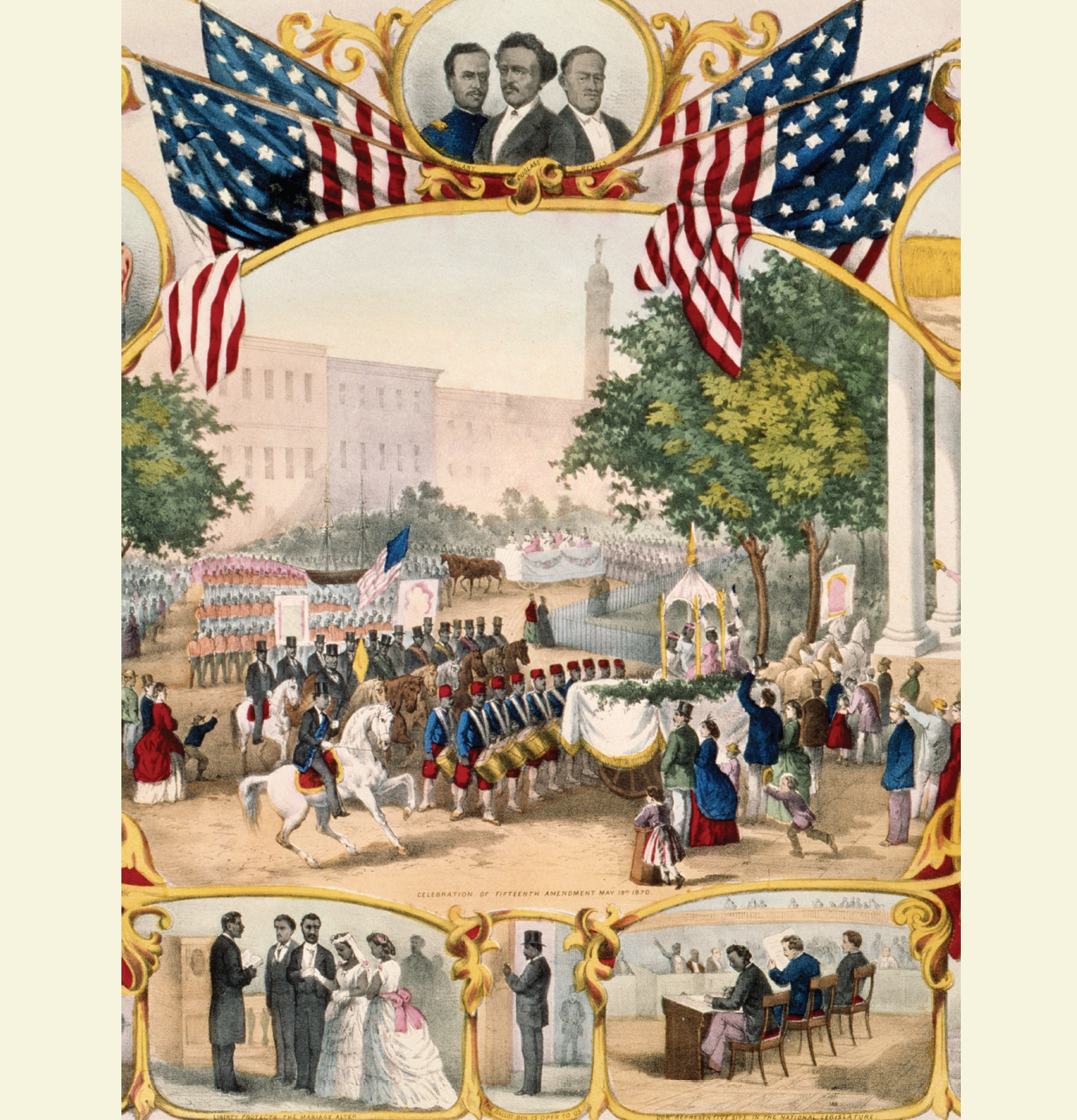

CHAPTER 15 Reconstruction, 1865–1877

IDENTIFY THE BIG IDEA

What goals did Republican policymakers, ex-Confederates, and freedpeople pursue during Reconstruction? To what degree did each succeed?

On the last day of April 1866, black soldiers in Memphis, Tennessee, turned in their weapons as they mustered out of the Union army. The next day, whites who resented the soldiers’ presence provoked a clash. At a street celebration where African Americans shouted “Hurrah for Abe Lincoln,” a white policeman responded, “Your old father, Abe Lincoln, is dead and damned.” The scuffle that followed precipitated three days of white violence and rape that left forty-eight African Americans dead and dozens more wounded. Mobs burned black homes and churches and destroyed all twelve of the city’s black schools.

Unionists were appalled. They had won the Civil War, but where was the peace? Ex-Confederates murdered freedmen and flagrantly resisted federal control. After the Memphis attacks, Republicans in Congress proposed a new measure that would protect African Americans by defining and enforcing U.S. citizenship rights. Eventually this bill became the most significant law to emerge from Reconstruction, the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

Andrew Johnson, however — the Unionist Democrat who became president after Abraham Lincoln’s assassination — refused to sign the bill. In May 1865, while Congress was adjourned, Johnson had implemented his own Reconstruction plan. It extended amnesty to all southerners who took a loyalty oath, except for a few high-ranking Confederates. It also allowed states to reenter the Union as soon as they revoked secession, abolished slavery, and relieved their new state governments of financial burdens by repudiating Confederate debts. A year later, at the time of the Memphis carnage, all ex-Confederate states had met Johnson’s terms. The president rejected any further intervention.

Johnson’s vetoes, combined with ongoing violence in the South, angered Unionist voters. In the political struggle that ensued, congressional Republicans seized the initiative from the president and enacted a sweeping program that became known as Radical Reconstruction. One of its key achievements would have been unthinkable a few years earlier: voting rights for African American men.

Black Southeners, though, had additional, urgent priorities. “We have toiled nearly all our lives as slaves [and] have made these lands what they are,” a group of South Carolina petitioners declared. They pleaded for “some provision by which we as Freedmen can obtain a Homestead.” Though northern Republicans and freedpeople agreed that black southerners must have physical safety and the right to vote, former slaves also wanted economic independence. Northerners sought, instead, to revive cash-crop plantations with wage labor. Reconstruction’s eventual failure stemmed from the conflicting goals of lawmakers, freedpeople, and relentlessly hostile ex-Confederates.