The Corporate Workplace

Before the Civil War, most American boys had hoped to become farmers, small-business owners, or independent artisans. Afterward, more and more Americans — both male and female — began working for someone else. Because they wore white shirts with starched collars, those who held professional positions in corporations became known as white-collar workers, a term differentiating them from blue-collar employees, who labored with their hands. For a range of employees — managers and laborers, clerks and salespeople — the rise of corporate work had wide-ranging consequences.

Managers and Salesmen As the managerial revolution unfolded, the headquarters of major corporations began to house departments handling specific activities such as purchasing and accounting. These departments were supervised by middle managers, something not seen before in American industry. Middle managers took on entirely new tasks, directing the flow of goods, labor, and information throughout the enterprise. They were key innovators, counterparts to the engineers in research laboratories who, in the same decades, worked to reduce costs and improve efficiency.

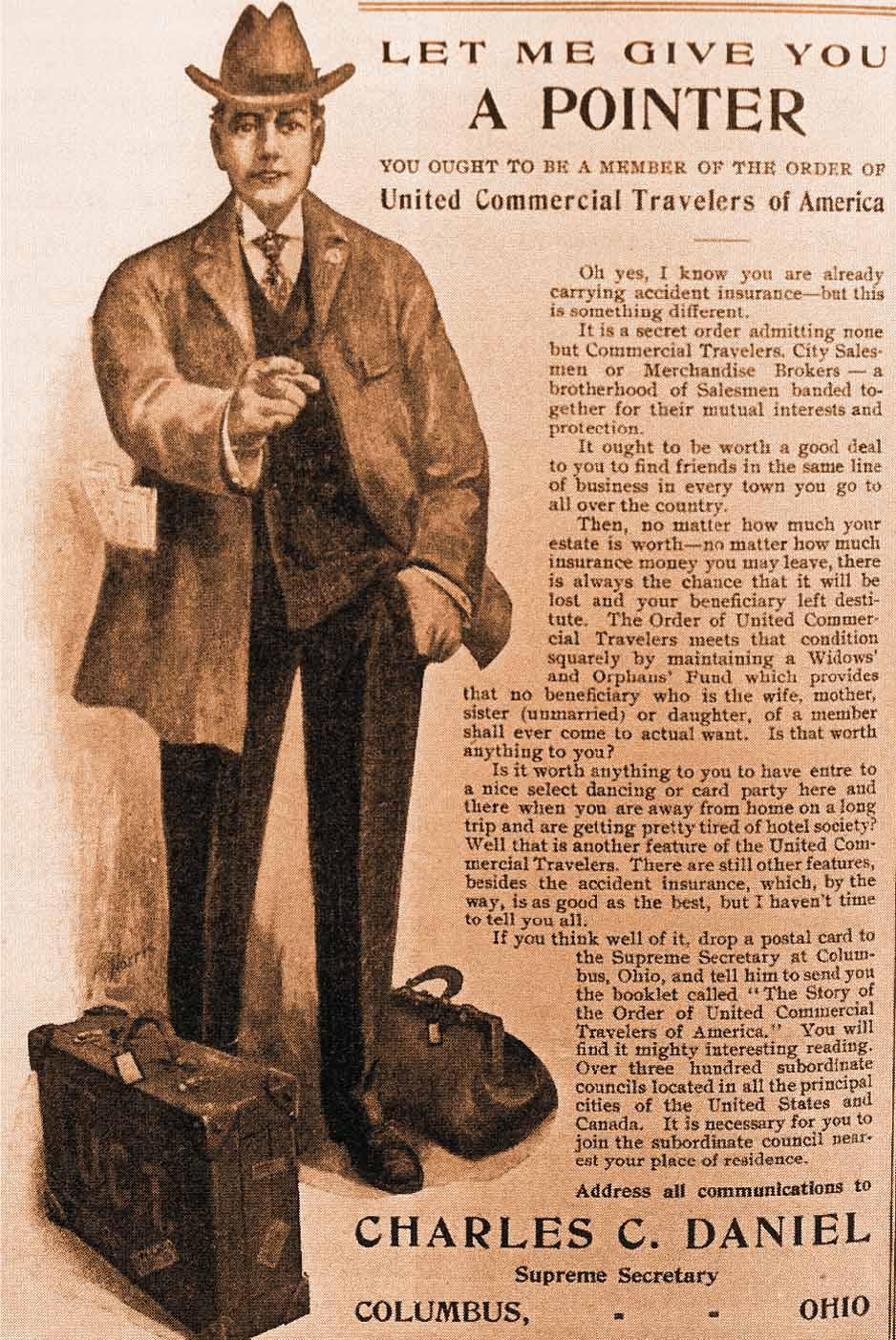

Corporations also needed a new kind of sales force. In post–Civil War America, the drummer, or traveling salesman, became a familiar sight on city streets and in remote country stores. Riding rail networks from town to town, drummers introduced merchants to new products, offered incentives, and suggested sales displays. They built nationwide distribution networks for such popular consumer products as cigarettes and Coca-Cola. By the late 1880s, the leading manufacturer of cash registers produced a sales script for its employees’ conversations with local merchants. “Take for granted that he will buy,” the script directed. “Say to him, ‘Now, Mr. Blank, what color shall I make it?’… Handing him your pen say, ‘Just sign here where I have made the cross.’”

With such companies in the vanguard, sales became systematized. Managers set individual sales quotas and awarded prizes to top salesmen, while those who sold too little were singled out for remedial training or dismissal. Executives embraced the ideas of business psychologist Walter Dill Scott, who published The Psychology of Advertising in 1908. Scott’s principles — which included selling to customers based on their presumed “instinct of escape” and “instinct of combat” — were soon taught at Harvard Business School. Others also promised that a “scientific attitude” would “attract attention” and “create desire.”

Women in the Corporate Office Beneath the ranks of managers emerged a new class of female office workers. Before the Civil War, most clerks at small firms had been young men who expected to rise through the ranks. In a large corporation, secretarial work became a dead-end job, and employers began assigning it to women. By the turn of the twentieth century, 77 percent of all stenographers and typists were female; by 1920, women held half of all low-level office jobs.

For white working-class women, clerking and office work represented new opportunities. In an era before most families had access to day care, mothers most often earned money at home, where they could tend children while also taking in laundry, caring for boarders, or doing piecework (sewing or other assembly projects, paid on a per-item basis). Unmarried daughters could enter domestic service or factory work, but clerking and secretarial work were cleaner and better paid.

New technologies provide additional opportunities for women. The rise of the telephone, introduced by inventor Alexander Graham Bell in 1876, was a notable example. Originally intended for business use on local exchanges, telephones were eagerly adopted by residential customers. Thousands of young women found work as telephone operators. By 1900, more than four million women worked for wages. About a third worked in domestic service; another third in industry; the rest in office work, teaching, nursing, or sales. As new occupations arose, the percentage of wage-earning women in domestic service dropped dramatically, a trend that continued in the twentieth century.

EXPLAIN CONSEQUENCES