On the Shop Floor

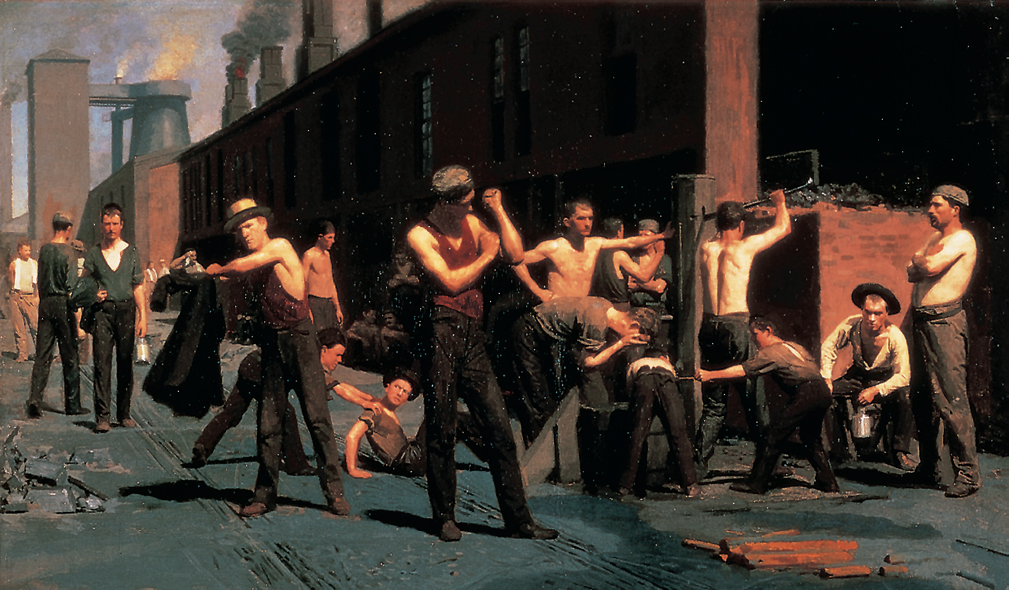

Despite the managerial revolution at the top, skilled craft workers — almost all of them men — retained considerable autonomy in many industries. A coal miner, for example, was not an hourly wageworker but essentially an independent contractor, paid by the amount of coal he produced. He provided his own tools, worked at his own pace, and knocked off early when he chose. The same was true for puddlers and rollers in iron works; molders in stove making; and machinists, glass blowers, and skilled workers in many other industries. Such workers abided by the stint, a self-imposed limit on how much they would produce each day. This informal system of restricting output infuriated efficiency-minded engineers, but to the workers it signified personal dignity, manly pride, and brotherhood with fellow employees. One shop in Lowell, Massachusetts, posted regulations requiring all employees to be at their posts by the time of the opening bell and to remain, with the shop door locked, until the closing bell. A machinist promptly packed his tools, declaring that he had not “been brought up under such a system of slavery.”

Skilled workers — craftsmen, inside contractors, and foremen — enjoyed a high degree of autonomy. But those who paid helpers from their own pocket could also exploit them. Subcontracting arose, in part, to enable manufacturers to distance themselves from the consequences of shady labor practices. In Pittsburgh steel mills, foremen were known as “pushers,” notorious for driving their gangs mercilessly. On the other hand, industrial labor operated on a human scale, through personal relationships that could be close and enduring. Striking craft workers would commonly receive the support of helpers and laborers, and labor gangs would sometimes walk out on behalf of a popular foreman.

As industrialization advanced, however, workers increasingly lost the independence characteristic of craft work. The most important cause of this was the deskilling of labor under a new system of mechanized manufacturing that men like meat-packer Gustavus Swift had pioneered, and that automobile maker Henry Ford would soon call mass production. Everything from typewriters to automobiles came to be assembled from standardized parts, using machines that increasingly operated with little human oversight. A machinist protested in 1883 that the sewing machine industry was so “subdivided” that “one man may make just a particular part of a machine and may not know anything whatever about another part of the same machine.” Such a worker, noted an observer, “cannot be master of a craft, but only master of a fragment.” Employers, who originally favored automatic machinery because it increased output, quickly found that it also helped them control workers and cut labor costs. They could pay unskilled workers less and replace them easily.

By the early twentieth century, managers sought to further reduce costs through a program of industrial efficiency called scientific management. Its inventor, a metal-cutting expert named Frederick W. Taylor, recommended that employers eliminate all brain work from manual labor, hiring experts to develop rules for the shop floor. Workers must be required to “do what they are told promptly and without asking questions or making suggestions.” In its most extreme form, scientific management called for engineers to time each task with a stopwatch; companies would pay workers more if they met the stopwatch standard. Taylor assumed that workers would respond automatically to the lure of higher earnings. But scientific management was not, in practice, a great success. Implementing it proved to be expensive, and workers stubbornly resisted. Corporate managers, however, adopted bits and pieces of Taylor’s system, and they enthusiastically agreed that decisions should lie with “management alone.” Over time, in comparison with businesses in other countries, American corporations created a particularly wide gap between the roles of managers and those of the blue-collar workforce.

Blue-collar workers had little freedom to negotiate, and their working conditions deteriorated markedly as mass production took hold. At the same time, industrialization brought cheaper products that enabled many Americans to enjoy new consumer products — if they could avoid starvation. From executives down to unskilled workers, the hierarchy of corporate employment contributed to sharper distinctions among three economic classes: the wealthy elite; an emerging, self-defined “middle class”; and a struggling class of workers, who bore the brunt of the economy’s new risks and included many Americans living in dire poverty. As it wrought these changes, industrialization prompted intense debate over inequality (Thinking Like a Historian).

Health Hazards and Pollution Industrialized labor also damaged workers’ health. In 1884, a study of the Illinois Central Railroad showed that, over the previous decade, one in twenty of its workers had been killed or permanently disabled by an accident on the job. For brakemen — one of the most dangerous jobs — the rate was one in seven. Due to lack of regulatory laws and inspections, mining was 50 percent more dangerous in the United States than in Germany; between 1876 and 1925, an average of over 2,000 U.S. coal miners died each year from caveins and explosions. Silver, gold, and copper mines were not immune from such tragedies, but mining companies resisted demands for safety regulation.

Extractive industries and factories also damaged nearby environments and the people who lived there. In big cities, poor residents suffered from polluted air and the dumping of noxious by-products into the water supply. Mines like those in Leadville, Colorado, contaminated the land and water with mercury and lead. Alabama convicts, forced to work in coal mines, faced brutal working conditions and fatal illnesses caused by the mines’ contamination of local water. At the time, people were well aware of many of these dangers, but workers had an even more urgent priority: work. Pittsburgh’s belching smokestacks meant coughing and lung damage, but they also meant running mills and paying jobs.

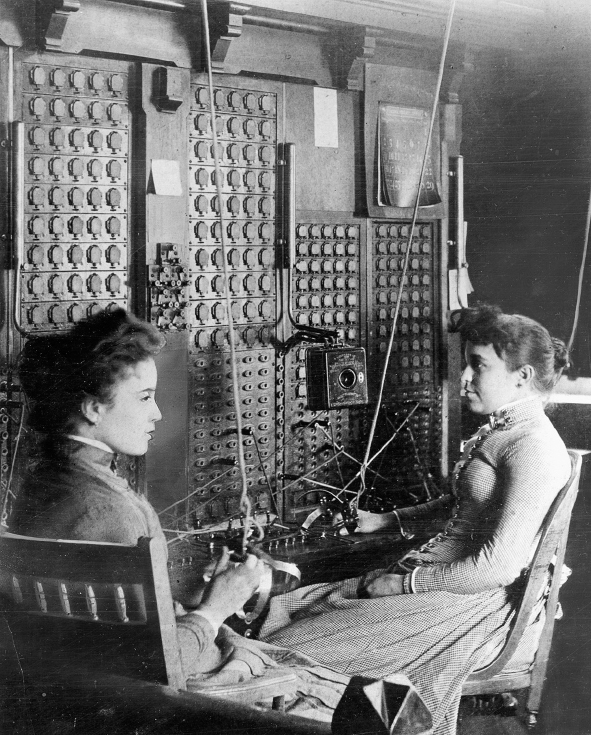

Unskilled Labor and Discrimination As managers deskilled production, the ranks of factory workers came to include more and more women and children, who were almost always unskilled and low paid. Men often resented women’s presence in factories, and male labor unions often worked to exclude women — especially wives, who they argued should remain in the home. Women vigorously defended their right to work. On hearing accusations that married women worked only to buy frivolous luxuries, one female worker in a Massachusetts shoe factory wrote a heated response to the local newspaper: “When the husband and father cannot provide for his wife and children, it is perfectly natural that the wife and mother should desire to work. … Don’t blame married women if the land of the free has become a land of slavery and oppression.”

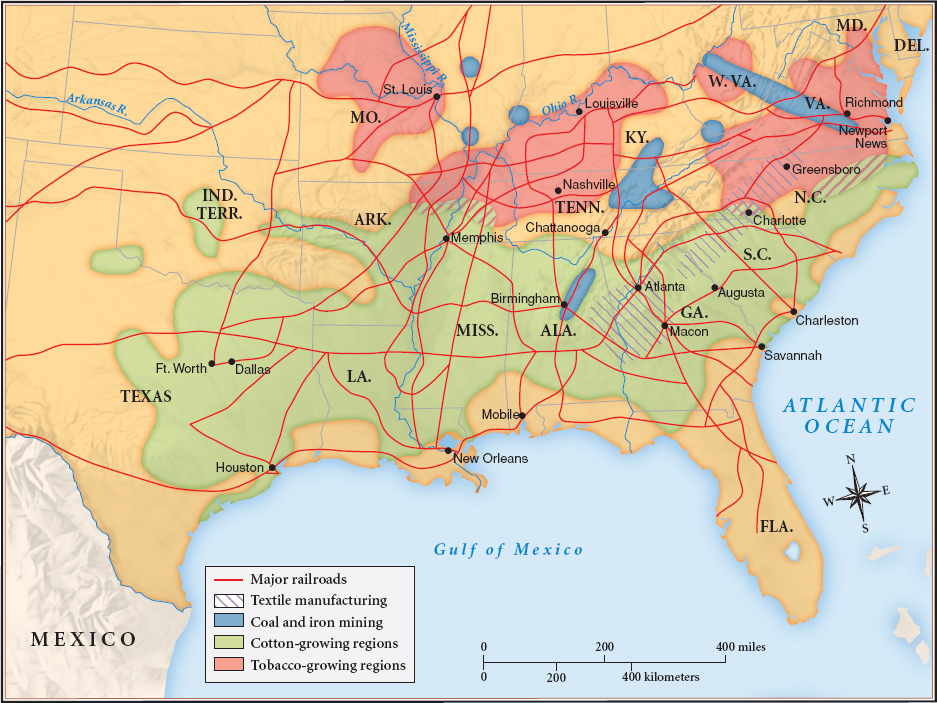

In 1900, one of every five children under the age of sixteen worked outside the home. Child labor was most widespread in the South, where a low-wage industrial sector emerged after Reconstruction (Map 17.1). Textile mills sprouted in the Carolinas and Georgia, recruiting workers from surrounding farms; whole families often worked in the mills. Many children also worked in Pennsylvania coal fields, where death and injury rates were high. State law permitted children as young as twelve to labor with a family member, but turn-of-the-century investigators estimated that about 10,000 additional boys, at even younger ages, were illegally employed in the mines.

Also at the bottom of the pay scale were most African Americans. Corporations and industrial manufacturers widely discriminated against them on the basis of race, and such prejudice was hardly limited to the South. After the Civil War, African American women who moved to northern cities were largely barred from office work and other new employment options; instead, they remained heavily concentrated in domestic service, with more than half employed as cooks or servants. African American men confronted similar exclusion. America’s booming vertically integrated corporations turned black men away from all but the most menial jobs. In 1890, almost a third of black men worked in personal service. Employers in the North and West recruited, instead, a different kind of low-wage labor: newly arrived immigrants.

TRACE CHANGE OVER TIME