The Movement for Social Settlements

Some urban reformers focused their energies on building a creative new institution, the social settlement. These community welfare centers investigated the plight of the urban poor, raised funds to address urgent needs, and helped neighborhood residents advocate on their own behalf. At the movement’s peak in the early twentieth century, dozens of social settlements operated across the United States. The most famous, and one of the first, was Hull House on Chicago’s West Side, founded in 1889 by Jane Addams and her companion Ellen Gates Starr. Their dilapidated mansion, flanked by saloons in a neighborhood of Italian and Eastern European immigrants, served as a spark plug for community improvement and political reform.

The idea for Hull House came partly from Toynbee Hall, a London settlement that Addams and Starr had visited while touring Europe. Social settlements also drew inspiration from U.S. urban missions of the 1870s and 1880s. Some of these, like the Hampton Institute, had aided former slaves during Reconstruction; others, like Grace Baptist in Philadelphia, arose in northern cities. To meet the needs of urban residents, missions offered employment counseling, medical clinics, day care centers, and sometimes athletic facilities in cooperation with the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA).

Jane Addams, a daughter of the middle class, first expected Hull House to offer art classes and other cultural programs for the poor. But Addams’s views quickly changed as she got to know her new neighbors and struggled to keep Hull House open during the depression of the 1890s. Addams’s views were also influenced by conversations with fellow Hull House resident Florence Kelley, who had studied in Europe and returned a committed socialist. Dr. Alice Hamilton, who opened a pediatric clinic at Hull House, wrote that Addams came to see her settlement as “a bridge between the classes. … She always held that this bridge was as much of a help to the well-to-do as to the poor.” Settlements offered idealistic young people “a place where they could live as neighbors and give as much as they could of what they had.”

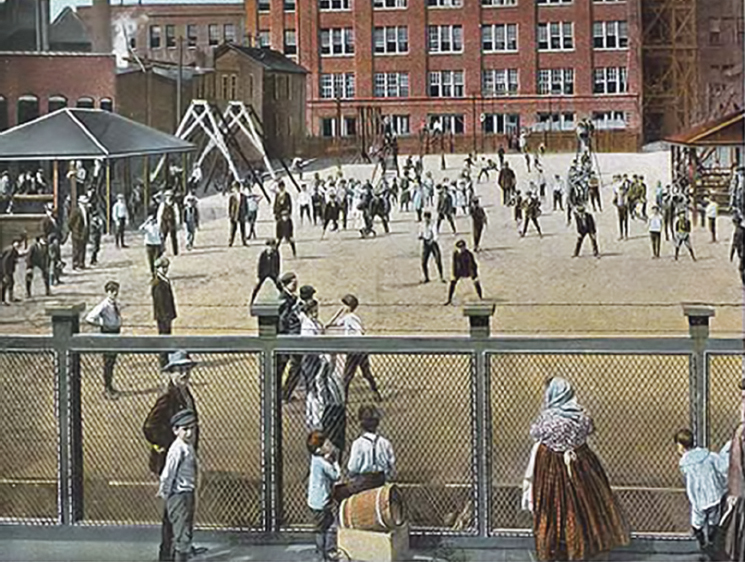

Addams and her colleagues believed that working-class Americans already knew what they needed. What they lacked were resources to fulfill those needs, as well as a political voice. These, settlement workers tried to provide. Hull House was typical in offering a bathhouse, playground, kindergarten, and day care center. Some settlements opened libraries and gymnasiums; others operated penny savings banks and cooperative kitchens where tired mothers could purchase a meal at the end of the day. (Addams humbly closed the Hull House kitchen when she found that her bland New England cooking had little appeal for Italians; her coworker, Dr. Alice Hamilton, soon investigated the health benefits of garlic.) At the Henry Street Settlement in New York, Lillian Wald organized visiting nurses to improve health in tenement wards. Addams, meanwhile, encouraged local women to inspect the neighborhood and bring back a list of dangers to health and safety. Together, they prepared a complaint to city council. The women, Addams wrote, had shown “civic enterprise and moral conviction” in carrying out the project themselves.

Social settlements took many forms. Some attached themselves to preexisting missions and African American colleges. Others were founded by energetic college graduates. Catholics ran St. Elizabeth Center in St. Louis; Jews, the Boston Hebrew Industrial School. Whatever their origins, social settlements were, in Addams’s words, “an experimental effort to aid in the solution of the social and industrial problems which are engendered by the modern condition of life in a great city.”

Settlements served as a springboard for many other projects. Settlement workers often fought city hall to get better schools and lobbied state legislatures for new workplace safety laws. At Hull House, Hamilton investigated lead poisoning and other health threats at local factories. Her colleague Julia Lathrop investigated the plight of teenagers caught in the criminal justice system. She drafted a proposal for separate juvenile courts and persuaded Chicago to adopt it. Pressuring the city to experiment with better rehabilitation strategies for juveniles convicted of crime, Lathrop created a model for juvenile court systems across the United States.

Another example of settlements’ long-term impact was the work of Margaret Sanger, a nurse who moved to New York City in 1911 and volunteered with a Lower East Side settlement. Horrified by women’s suffering from constant pregnancies — and remembering her devout Catholic mother, who had died young after bearing eleven children — Sanger launched a crusade for what she called birth control. Her newspaper column, “What Every Girl Should Know,” soon garnered an indictment for violating obscenity laws. The publicity that resulted helped Sanger launch a national birth control movement.

Settlements were thus a crucial proving ground for many progressive experiments, as well as for the emerging profession of social work, which transformed the provision of public welfare. Social workers rejected the older model of private Christian charity, dispensed by well-meaning middle-class volunteers to those in need. Instead, social workers defined themselves as professional caseworkers who served as advocates of social justice. Like many reformers of the era, they allied themselves with the new social sciences, such as sociology and economics, and undertook statistical surveys and other systematic methods for gathering facts. Social work proved to be an excellent opportunity for educated women who sought professional careers. By 1920, women made up 62 percent of U.S. social workers.

TRACE CHANGE OVER TIME