Newcomers and Neighborhoods

Explosive population growth made cities a world of new arrivals, including many young women and men arriving from the countryside. Traditionally, rural daughters had provided essential labor for spinning and weaving cloth, but industrialization relocated those tasks from the household to the factory. Finding themselves without a useful household role, many farm daughters sought paid employment. In an age of declining rural prosperity, many sons also left the farm and — like immigrants arriving from other countries — set aside part of their pay to help the folks at home. Explaining why she moved to Chicago, an African American woman from Louisiana declared, “A child with any respect about herself or hisself wouldn’t like to see their mother and father work so hard and earn nothing. I feel it my duty to help.”

America’s cities also became homes for millions of overseas immigrants. Most numerous in Boston were the Irish; in Minneapolis, Swedes; in other northern cities, Germans. Arriving in a great metropolis, immigrants confronted many difficulties. One Polish man, who had lost the address of his American cousins, felt utterly alone after disembarking at New York’s main immigration facility, Ellis Island, which opened in 1892. Then he heard a kindly voice in Polish, offering to help. “From sheer joy,” he recalled, “tears welled up in my eyes to hear my native tongue.” Such experiences suggest why immigrants stuck together, relying on relatives and friends to get oriented and find jobs. A high degree of ethnic clustering resulted, even within a single factory. At the Jones and Laughlin steelworks in Pittsburgh, for example, the carpentry shop was German, the hammer shop Polish, and the blooming mill Serbian. “My people …stick together,” observed a son of Ukrainian immigrants. But he added, “We who are born in this country …feel this country is our home.”

Patterns of settlement varied by ethnic group. Many Italians, recruited by padroni, or labor bosses, found work in northeastern and Mid-Atlantic cities. Their urban concentration was especially marked after the 1880s, as more and more laborers arrived from southern Italy. The attraction of America was obvious to one young man, who had grown up in a poor southern Italian farm family. “I had never gotten any wages of any kind before,” he reported after settling with his uncle in New Jersey. “The work here was just as hard as that on the farm; but I didn’t mind it much because I would receive what seemed to me like a lot.” Amadeo Peter Giannini, who started off as a produce merchant in San Francisco, soon turned to banking. After the San Francisco earthquake in 1906, his Banca d’Italia was the first financial institution to reopen in the Bay area. Expanding steadily across the West, it eventually became Bank of America.

Like Giannini’s bank, institutions of many kinds sprang up to serve ethnic urban communities. Throughout America, Italian speakers avidly read the newspaper Il Progresso Italo-Americano; Jews, the Yiddish-language Jewish Daily Forward, also published in New York. Bohemians gathered in singing societies, while New York Jews patronized a lively Yiddish theater. By 1903, Italians in Chicago had sixty-six mutual aid societies, most composed of people from a particular province or town. These societies collected dues from members and paid support in case of death or disability on the job. Mutual benefit societies also functioned as fraternal clubs. “We are strangers in a strange country,” explained one member of a Chinese tong, or mutual aid society, in Chicago. “We must have an organization (tong) to control our country fellows and develop our friendship.”

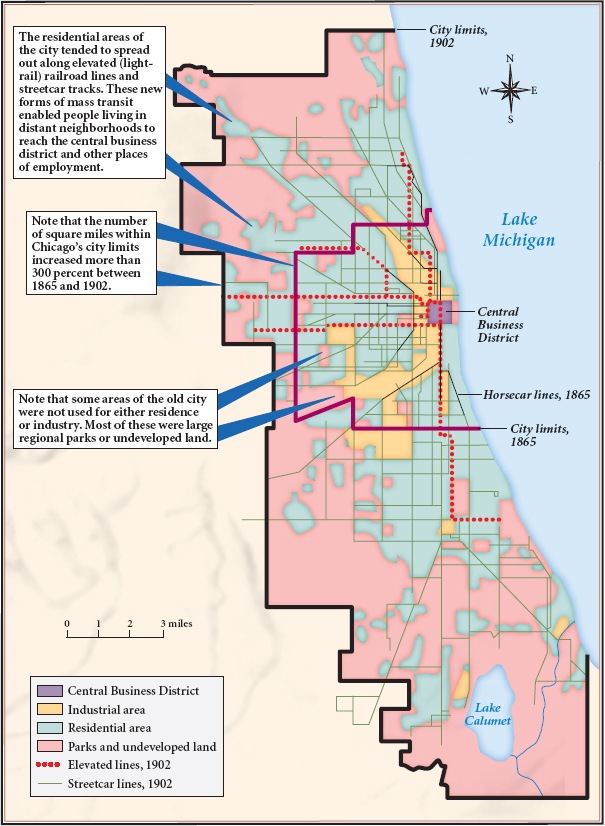

Sharply defined ethnic neighborhoods such as San Francisco’s Chinatown, Italian North Beach, and Jewish Hayes Valley grew up in every major city, driven by both discrimination and immigrants’ desire to stick together (Map 19.1). In addition to patterns of ethnic and racial segregation, residential districts in almost all industrial cities divided along lines of economic class. Around Los Angeles’s central plaza, Mexican neighborhoods diversified, incorporating Italians and Jews. Later, as the plaza became a site for business and tourism, immigrants were pushed into working-class neighborhoods like Belvedere and Boyle Heights, which sprang up to the east. Though ethnically diverse, East Los Angeles was resolutely working class; middle-class white neighborhoods grew up predominantly in West Los Angeles.

African Americans also sought urban opportunities. In 1900, almost 90 percent of American blacks still lived in the South, but increasing numbers had moved to cities such as Baton Rouge, Jacksonville, Montgomery, and Charleston, all of whose populations were more than 50 percent African American. Blacks also settled in northern cities, albeit not in the numbers that would arrive during the Great Migration of World War I. Though blacks constituted only 2 percent of New York City’s population in 1910, they already numbered more than 90,000. These newcomers confronted conditions even worse than those for foreign-born immigrants. Relentlessly turned away from manufacturing jobs, most black men and women took up work in the service sector, becoming porters, laundrywomen, and domestic servants.

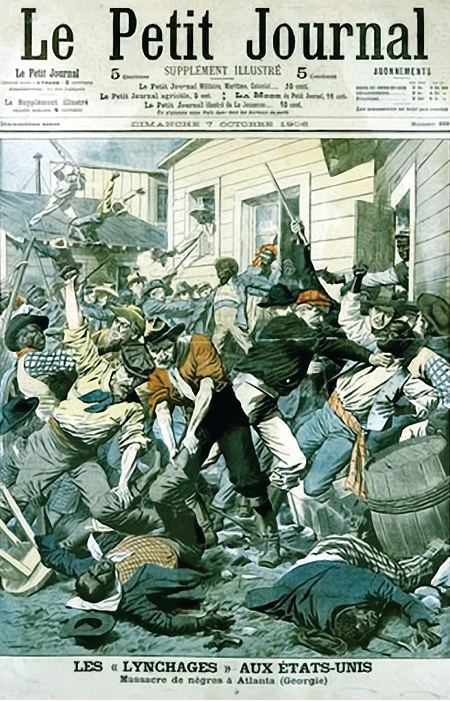

Blacks faced another urban danger: the so-called race riot, an attack by white mobs triggered by street altercations or rumors of crime. One of the most virulent episodes occurred in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1906. The violence was fueled by a nasty political campaign that generated sensational false charges of “negro crime.” Roaming bands of white men attacked black Atlantans, invading middle-class black neighborhoods and in one case lynching two barbers after seizing them in their shop. The rioters killed at least twenty-four blacks and wounded more than a hundred. The disease of hatred was not limited to the South. Race riots broke out in New York City’s Tenderloin district (1900); Evansville, Indiana (1903); and Springfield, Illinois (1908). By then, one journalist observed, “In every important Northern city, a distinct race-problem already exists which must, in a few years, assume serious proportions.”

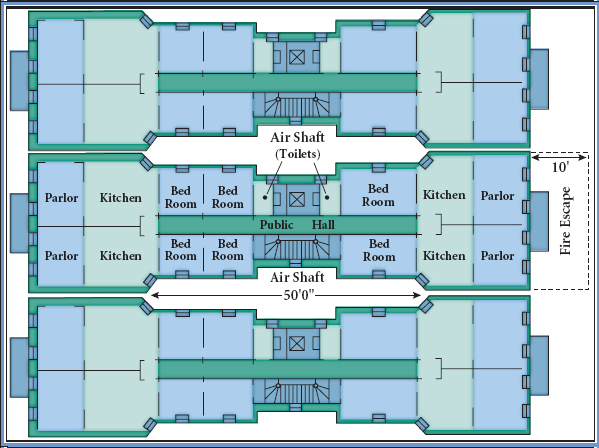

Whether they arrived from the South or from Europe, Mexico, or Asia, working-class city residents needed cheap housing near their jobs (Map 19.2). They faced grim choices. As urban land values climbed, speculators tore down houses that were vacated by middle-class families moving away from the industrial core. In their place, they erected five- or six-story tenements, buildings that housed twenty or more families in cramped, airless apartments (Figure 19.1). Tenements fostered rampant disease and horrific infant mortality. In New York’s Eleventh Ward, an average of 986 persons occupied each acre. One investigator in Philadelphia described twenty-six people living in nine rooms of a tenement. “The bathroom at the rear of the house was used as a kitchen,” she reported. “One privy compartment in the yard was the sole toilet accommodation for the five families living in the house.” African Americans often suffered most. A study of Albany, Syracuse, and Troy, New York, noted, “The colored people are relegated to the least healthful buildings.”

Denouncing these conditions, reformers called for model tenements financed by public-spirited citizens willing to accept a limited return on their investment. When private philanthropy failed to make a dent, cities turned to housing codes. The most advanced was New York’s Tenement House Law of 1901, which required interior courts, indoor toilets, and fire safeguards for new structures. The law, however, had no effect on the 44,000 tenements that already existed in Manhattan and the Bronx. Reformers were thwarted by the economic facts of urban development. Industrial workers could not afford transportation and had to live near their jobs; commercial development pushed up land values. Only high-density, cheaply built housing earned landlords a significant profit.

PLACE EVENTS IN CONTEXT