Introduction for Chapter 22

CHAPTER 22 Cultural Conflict, Bubble, and Bust, 1919–1932

IDENTIFY THE BIG IDEA

What conflicts in culture and politics arose in the 1920s, and how did economic developments in that decade help cause the Great Depression?

Rising to fame in The Sheik (1922), Rudolph Valentino became a controversial Hollywood star. Calling him “dark, darling, and delightful,” female fans mobbed his appearances. In Chicago, Mexican American boys slicked back their hair and called each other “sheik.” But some Anglo men said they loathed Valentino. One reviewer claimed the star had stolen his style from female “vamps” and ridiculed him for wearing a bracelet (a gift from his wife). The Chicago Tribune blamed Valentino for the rise of “effeminate men,” shown by the popularity of “floppy pants and slave bracelets.” Outraged, Valentino challenged the journalist to a fight — and defeated the writer’s stand-in.

Valentino, an Italian immigrant, upset racial and ethnic boundaries. Nicknamed the Latin Lover, he played among other roles a Spanish bullfighter and the son of a maharajah. When a reporter called his character in The Sheik a “savage,” Valentino retorted, “People are not savages because they have dark skins. The Arab civilization is one of the oldest in the world.”

But to many American-born Protestants, movies were morally dangerous — “vile and atrocious,” one women’s group declared. The appeal of “dark” stars like Valentino and his predecessor, Japanese American actor Sessue Hayakawa, was part of the problem. Hollywood became a focal point for political conflict as the nation took a sharp right turn. A year before The Sheik appeared, the Reverend Wilbur Crafts published a widely reprinted article warning of “Jewish Supremacy in Film.” He accused “Hebrew” Hollywood executives of “gross immorality” and claimed they were racially incapable of understanding “the prevailing standards of the American people.” These were not fringe views. Crafts’s editorial first appeared in a newspaper owned by prominent automaker Henry Ford.

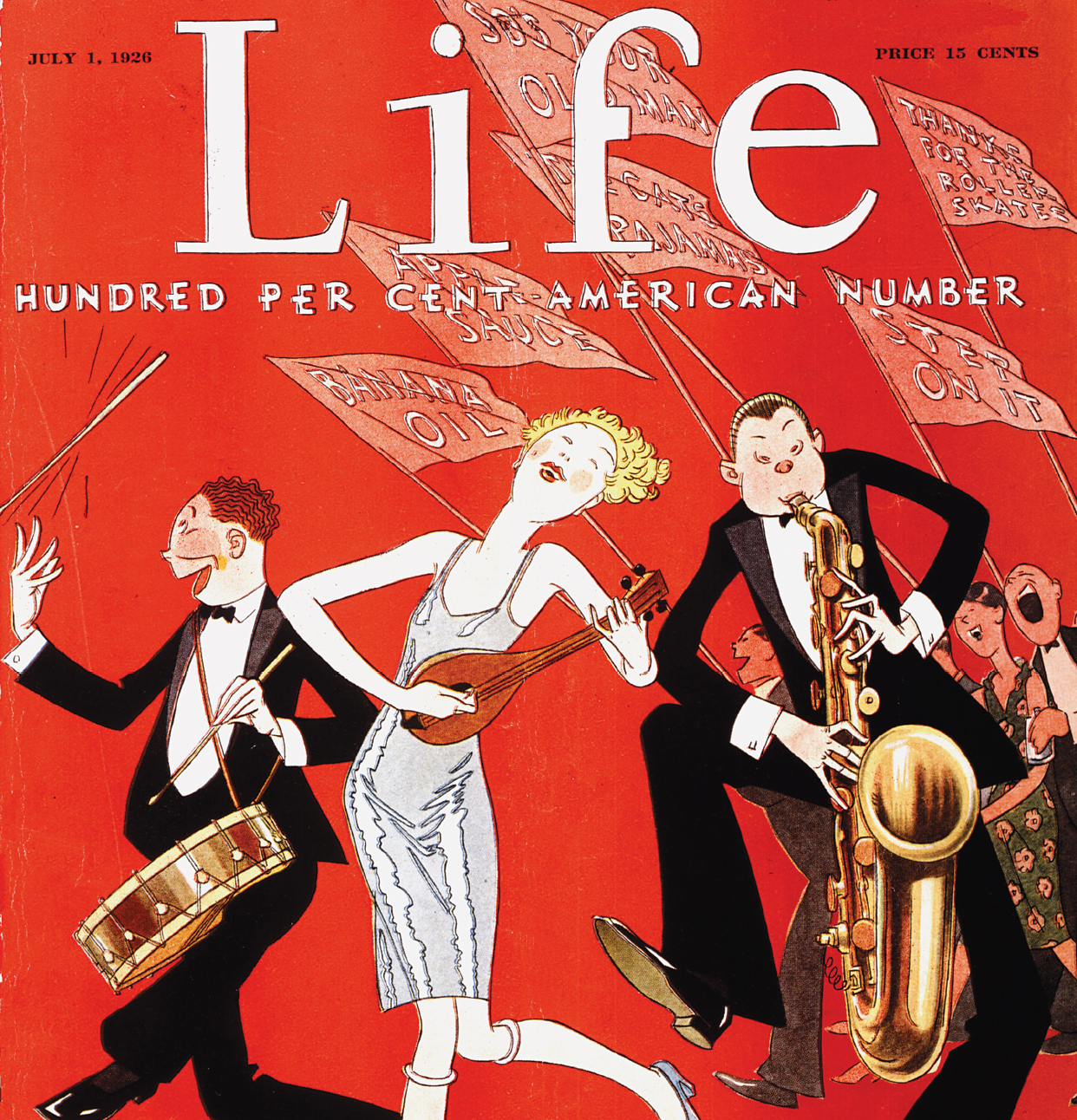

Critics, though, failed to slow Hollywood’s success. Faced with threats of regulation, movie-makers did what other big businesses did in the 1920s: they used their clout to block government intervention. At the same time, they expanded into world markets; when Valentino visited Paris, he was swarmed by thousands of French fans. The Sheik highlighted America’s business success and its political and cultural divides. Young urban audiences, including women “flappers,” were eager to challenge older sexual and religious mores. Rural Protestants saw American values going down the drain. In Washington, meanwhile, Republican leaders abandoned two decades of reform and deferred to business. Americans wanted prosperity, not progressivism — until the consequences arrived in the shock of the Great Depression.