A People’s Democracy

In 1939, writer John La Touche and musician Earl Robinson produced “Ballad for Americans.” A patriotic song, it called for uniting “everybody who’s nobody … Irish, Negro, Jewish, Italian, French, and English, Spanish, Russian, Chinese, Polish, Scotch, Hungarian, Litvak, Swedish, Finnish, Canadian, Greek, and Turk, and Czech and double Czech American.” The song captured the democratic aspirations that the New Deal had awakened. Millions of ordinary people believed that the nation could, and should, become more egalitarian. Influenced by the liberal spirit of the New Deal, Americans from all walks of life seized the opportunity to push for change in the nation’s social and political institutions.

Organized Labor Demoralized and shrinking during the 1920s, labor unions increased their numbers and clout during the New Deal, thanks to the Wagner Act. “The era of privilege and predatory individuals is over,” labor leader John L. Lewis declared. By the end of the decade, the number of unionized workers had tripled to 23 percent of the nonagricultural workforce. A new union movement, led by the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), promoted “industrial unionism” — organizing all the workers in an industry, from skilled machinists to unskilled janitors, into a single union. The American Federation of Labor (AFL), representing the other major group of unions, favored organizing workers on a craft-by-craft basis. Both federations dramatically increased their membership in the second half of the 1930s.

Labor’s new vitality translated into political action and a long-lasting alliance with the Democratic Party. The CIO helped fund Democratic campaigns in 1936, and its political action committee became a major Democratic contributor during the 1940s. These successes were real but limited. The labor movement did not become the dominant force in the United States that it was in Europe, and unions never enrolled a majority of American wageworkers. Antiunion employer groups such as the National Association of Manufacturers and the Chamber of Commerce remained powerful forces in American business life. After a decade of gains, organized labor remained an important, but secondary, force in American industry.

Women and the New Deal Because policymakers saw the depression primarily as a crisis of male breadwinners, the New Deal did not directly challenge gender inequities. New Deal measures generally enhanced women’s welfare, but few addressed their specific needs and concerns. However, the Roosevelt administration did welcome women into the higher ranks of government. Frances Perkins, the first woman named to a cabinet post, served as secretary of labor throughout Roosevelt’s presidency. While relatively few, female appointees often worked to open up other opportunities in government for talented women.

The most prominent woman in American politics was the president’s wife, Eleanor Roosevelt. In the 1920s, she had worked to expand positions for women in political parties, labor unions, and education. A tireless advocate for women’s rights, during her years in the White House Mrs. Roosevelt emerged as an independent public figure and the most influential First Lady in the nation’s history. Descending into coal mines to view working conditions, meeting with African Americans seeking antilynching laws, and talking to people on breadlines, she became the conscience of the New Deal, pushing her husband to do more for the disadvantaged. “I sometimes acted as a spur,” Mrs. Roosevelt later reflected, “even though the spurring was not always wanted or welcome.”

Without the intervention of Eleanor Roosevelt, Frances Perkins, and other prominent women, New Deal policymakers would have largely ignored the needs of women. A fourth of the National Recovery Act’s employment rules set a lower minimum wage for women than for men performing the same jobs, and only 7 percent of the workers hired by the Civil Works Administration were female. The Civilian Conservation Corps excluded women entirely. Women fared better under the Works Progress Administration; at its peak, 405,000 women were on the payroll. Most Americans agreed with such policies. When Gallup pollsters in 1936 asked people whether wives should work outside the home when their husbands had jobs, 82 percent said no. Such sentiment reflected a persistent belief in women’s secondary status in American economic life.

African Americans Under the New Deal Across the nation, but especially in the South, African Americans held the lowest-paying jobs and faced harsh social and political discrimination. Though FDR did not fundamentally change this fact, he was the most popular president among African Americans since Abraham Lincoln. African Americans held 18 percent of WPA jobs, although they constituted 10 percent of the population. The Resettlement Administration, established in 1935 to help small farmers and tenants buy land, actively protected the rights of black tenant farmers. Black involvement in the New Deal, however, could not undo centuries of racial subordination, nor could it change the overwhelming power of southern whites in the Democratic Party.

Nevertheless, black Americans received significant benefits from New Deal relief programs and believed that the White House cared about their plight, which caused a momentous shift in their political allegiance. Since the Civil War, black voters had staunchly supported the Republican Party, the party of Abraham Lincoln, known as the Great Emancipator. Even in the depression year of 1932, they overwhelmingly supported Republican candidates. But in 1936, as part of the tidal wave of national support for FDR, northern African Americans gave Roosevelt 71 percent of their votes and have remained solidly Democratic ever since.

African Americans supported the New Deal partly because the Roosevelt administration appointed a number of black people to federal office, and an informal “black cabinet” of prominent African American intellectuals advised New Deal agencies. Among the most important appointees was Mary McLeod Bethune. Born in 1875 in South Carolina to former slaves, Bethune founded Bethune-Cookman College and served during the 1920s as president of the National Association of Colored Women. She joined the New Deal in 1935, confiding to a friend that she “believed in the democratic and humane program” of FDR. Americans, Bethune observed, had to become “accustomed to seeing Negroes in high places.” Bethune had access to the White House and pushed continually for New Deal programs to help African Americans.

But the New Deal was limited in its approach to race. Roosevelt did not go further in support of black rights, because of both his own racial blinders and his need for the votes of the white southern Democrats in Congress — including powerful southern senators, many of whom held influential committee posts in Congress. Most New Deal programs reflected prevailing racial attitudes. Roosevelt and other New Dealers had to trim their proposals of measures that would substantially benefit African Americans. Civilian Conservation Corps camps segregated blacks, and most NRA rules did not protect black workers from discrimination. Both Social Security and the Wagner Act explicitly excluded the domestic and agricultural jobs held by most African Americans in the 1930s. Roosevelt also refused to support legislation making lynching a federal crime, which was one of the most pressing demands of African Americans in the 1930s. Between 1882 and 1930, more than 2,500 African Americans were lynched by white mobs in the southern states, which means that statistically, one man, woman, or child was murdered every week for fifty years. But despite pleas from black leaders, and from Mrs. Roosevelt herself, FDR feared that southern white Democrats would block his other reforms in retaliation for such legislation.

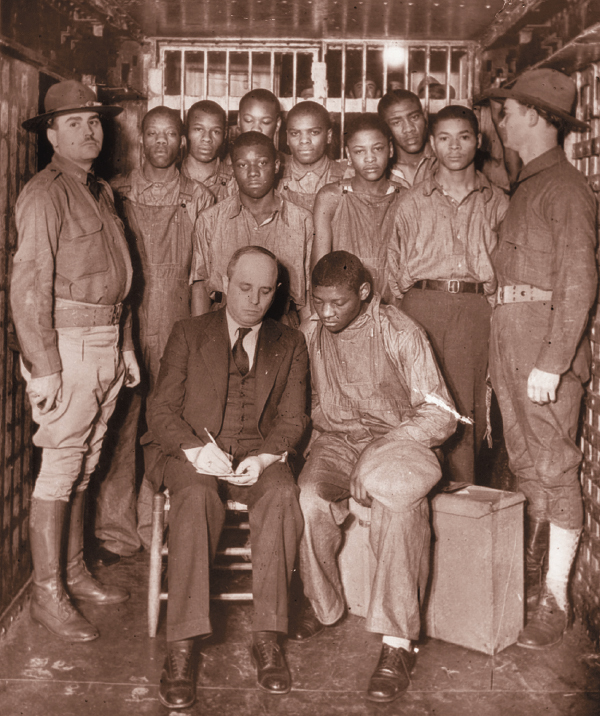

If lynching embodied southern lawlessness, southern law was not much better. In an infamous 1931 case in Scottsboro, Alabama, nine young black men were accused of rape by two white women hitching a ride on a freight train. The women’s stories contained many inconsistencies, but within weeks a white jury had convicted all nine defendants; eight received the death sentence. After the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the sentences because the defendants had been denied adequate legal counsel, five of the men were again convicted and sentenced to long prison terms. Across the country, the Scottsboro Boys, as they were known, inspired solidarity within African American communities. Among whites, the Communist Party took the lead in publicizing the case — and was one of the only white organizations to do so — helping to support the Scottsboro Defense Committee, which raised money for legal efforts on the defendants’ behalf.

In southern agriculture, where many sharecroppers were black while landowners and government administrators were white, the Agricultural Adjustment Act hurt rather than helped the poorest African Americans. White landowners collected government subsidy checks but refused to distribute payments to their sharecroppers. Such practices forced 200,000 black families off the land. Some black farmers tried to protect themselves by joining the Southern Tenant Farmers Union (STFU), a biracial organization founded in 1934. “The same chain that holds you holds my people, too,” an elderly black farmer reminded his white neighbors. But landowners had such economic power and such support from local sheriffs that the STFU could do little.

A generation of African American leaders came of age inspired by the New Deal’s democratic promise. But it remained just a promise. From the outset, New Dealers wrestled with potentially fatal racial politics. Franklin Roosevelt and the Democratic Party depended heavily on white voters in the South, who were determined to maintain racial segregation and white supremacy. But many Democrats in the North and West — centers of New Deal liberalism — would come to oppose racial discrimination. This meant, ironically, that the nation’s most liberal political forces and some of its most conservative political forces existed side by side in the same political party. Another thirty years would pass before black Americans would gain an opportunity to reform U.S. racial laws and practices.

Indian Policy New Deal reformers seized the opportunity to implement their vision for the future of Native Americans, with mixed results. Indian peoples had long been one of the nation’s most disadvantaged and powerless groups. In 1934, the average individual Indian income was only $48 per year, and the Native American unemployment rate was three times the national average. The plight of Native Americans won the attention of the progressive commissioner of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), John Collier, an intellectual and critic of past BIA practices. Collier understood what Native Americans had long known: that the government’s decades-long policy of forced assimilation, prohibition of Indian religions, and confiscation of Indian lands had left most tribes poor, isolated, and without basic self-determination.

Collier helped to write and push through Congress the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, sometimes called the Indian New Deal. On the positive side, the law reversed the Dawes Act of 1887 by promoting Indian self-government through formal constitutions and democratically elected tribal councils. A majority of Indian peoples — some 181 tribes — accepted the reorganization policy, but 77 declined to participate, primarily because they preferred the traditional way of making decisions by consensus rather than by majority vote. Through the new law, Indians won a greater degree of religious freedom, and tribal governments regained their status as semisovereign dependent nations. When the latter policy was upheld by the courts, Indian people gained a measure of leverage that would have major implications for native rights in the second half of the twentieth century.

Like so many other federal Indian policies, however, the “Indian New Deal” was a mixed blessing. For some peoples, the act imposed a model of self-government that proved incompatible with tribal traditions and languages. The Papagos of southern Arizona, for instance, had no words for budget or representative, and they made no linguistic distinctions among law, rule, charter, and constitution. In another case, the nation’s largest tribe, the Navajos, rejected the BIA’s new policy, largely because the government was simultaneously reducing Navajo livestock to protect the Boulder Dam project. In theory, the new policy gave Indians a much greater degree of self-determination. In practice, however, although some tribes did benefit, the BIA and Congress continued to interfere in internal Indian affairs and retained financial control over reservation governments.

Struggles in the West By the 1920s, agriculture in California had become a big business — intensive, diversified, and export-oriented. Large-scale corporate-owned farms produced specialty crops — lettuce, tomatoes, peaches, grapes, and cotton — whose staggered harvests allowed the use of transient laborers. Thousands of workers, immigrants from Mexico and Asia and white migrants from the midwestern states, trooped from farm to farm and from crop to crop during the long picking season. Some migrants settled in the rapidly growing cities along the West Coast, especially the sprawling metropolis of Los Angeles. Under both Hoover and FDR, the federal government promoted the “repatriation” of Mexican citizens — their deportation to Mexico. Between 1929 and 1937, approximately half a million people of Mexican descent were deported. But historians estimate that more than 60 percent of these were legal U.S. citizens, making the government’s actions constitutionally questionable.

Despite the deportations, many Mexican Americans benefitted from the New Deal and generally held Roosevelt and the Democratic Party in high regard. People of Mexican descent, like other Americans, took jobs with the WPA and the CCC, or received relief in the worst years of the depression. The National Youth Administration (NYA), which employed young people from families on relief and sponsored a variety of school programs, was especially important in southwestern cities. In California, the Mexican American Movement (MAM), a youth-focused organization, received assistance from liberal New Dealers. New Deal programs did not fundamentally improve the migrant farm labor system under which so many people of Mexican descent labored, but Mexicans joined the New Deal coalition in large numbers because of the Democrats’ commitment to ordinary Americans. “Franklin D. Roosevelt’s name was the spark that started thousands of Spanish-speaking persons to the polls,” noted one Los Angeles activist.

Men and women of Asian descent — mostly from China, Japan, and the Philippines — formed a small minority of the American population but were a significant presence in some western cities. Immigrants from Japan and China had long faced discrimination. A 1913 California law prohibited them from owning land. Japanese farmers, who specialized in fruit and vegetable crops, circumvented this restriction by putting land titles in the names of their American-born children. As the depression cut farm prices and racial discrimination excluded young Japanese Americans from nonfarm jobs, about 20 percent of the immigrants returned to Japan.

Chinese Americans were less prosperous than their Japanese counterparts. Only 3 percent of Chinese Americans worked in professional and technical positions, and discrimination barred them from most industrial jobs. In San Francisco, the majority of Chinese worked in small businesses: restaurants, laundries, and firms that imported textiles and ceramics. During the depression, they turned for assistance to Chinese social organizations such as huiguan (district associations) and to the city government; in 1931, about one-sixth of San Francisco’s Chinese population was receiving public aid. But few Chinese benefitted from the New Deal. Until the repeal of the Exclusion Act in 1943, Chinese immigrants were classified as “aliens ineligible for citizenship” and therefore were excluded from most federal programs.

Because Filipino immigrants came from a U.S. territory, they were not affected by the ban on Asian immigration enacted in 1924. During the 1920s, their numbers swelled to about 50,000, many of whom worked as laborers on large corporate-owned farms. As the depression cut wages, Filipino immigration slowed to a trickle, and it was virtually cut off by the Tydings-McDuffie Act of 1934. The act granted independence to the Philippines (which since 1898 had been an American colony), classified all Filipinos in the United States as aliens, and restricted immigration from the Philippines to fifty people per year.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST