Reshaping the Environment

Attention to natural resources was a dominant theme of the New Deal, and the shaping of the landscape was among its most visible legacies. Franklin Roosevelt and Interior Secretary Harold Ickes saw themselves as conservationists in the tradition of FDR’s cousin, Theodore Roosevelt. In an era before environmentalism, FDR practiced what he called the “gospel of conservation.” The president cared primarily about making the land — and other natural resources, such as trees and water — better serve human needs. National policy stressed scientific land management and ecological balance. Preserving wildlife and wilderness was of secondary importance. Under Roosevelt, the federal government both responded to environmental crises and reshaped the use of natural resources, especially water, in the United States.

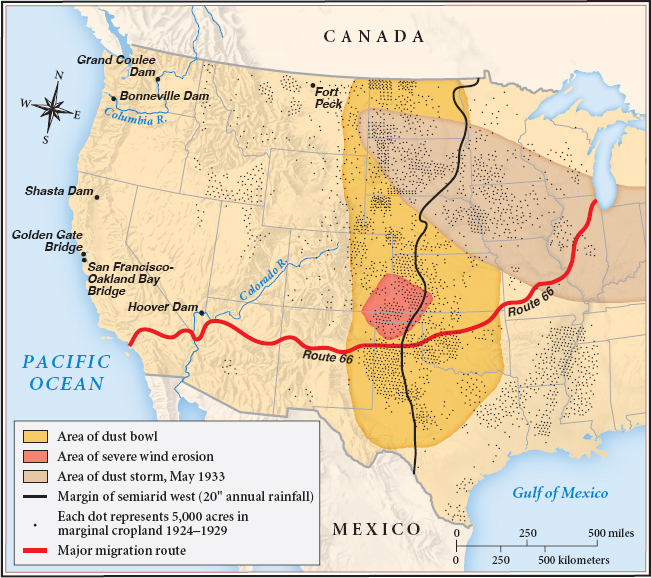

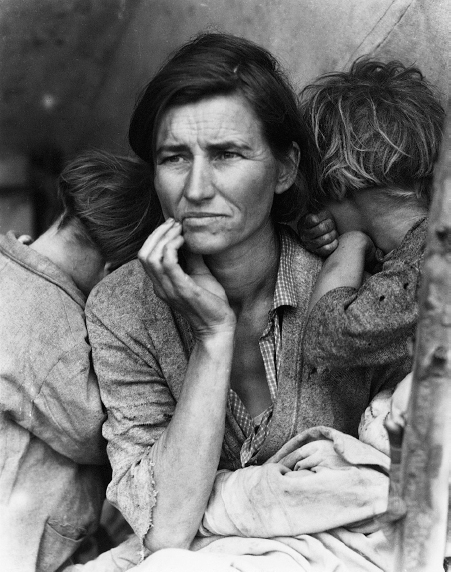

The Dust Bowl Among the most hard-pressed citizens during the depression were farmers fleeing the “dust bowl” of the Great Plains. Between 1930 and 1941, a severe drought afflicted the semiarid states of Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico, Colorado, Arkansas, and Kansas. Farmers in these areas had stripped the land of its native vegetation, which destroyed the delicate ecology of the plains. To grow wheat and other crops, they had pushed agriculture beyond the natural limits of the soil, making their land vulnerable, in times of drought, to wind erosion of the topsoil (Map 23.4). When the winds came, huge clouds of thick dust rolled over the land, turning the day into night. This ecological disaster prompted a mass exodus. At least 350,000 “Okies” (so called whether or not they were from Oklahoma) loaded their belongings into cars and trucks and headed to California. John Steinbeck’s novel The Grapes of Wrath (1939) immortalized them, and New Deal photographer Dorothea Lange’s haunting images of California migrant camps made them the public face of the depression’s human toll.

Roosevelt and Ickes believed that poor land practices made for poor people. Under their direction, government agencies tackled the dust bowl’s human causes. Agents from the newly created Soil Conservation Service, for instance, taught farmers to prevent soil erosion by tilling hillsides along the contours of the land. They also encouraged (and sometimes paid) farmers to take certain commercial crops out of production and plant soil-preserving grasses instead. One of the U.S. Forest Service’s most widely publicized programs was the Shelterbelts, the planting of 220 million trees running north along the 99th meridian from Abilene, Texas, to the Canadian border. Planted as a windbreak, the trees also prevented soil erosion. A variety of government agencies, from the CCC to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, lent their expertise to establishing sound farming practices in the plains.

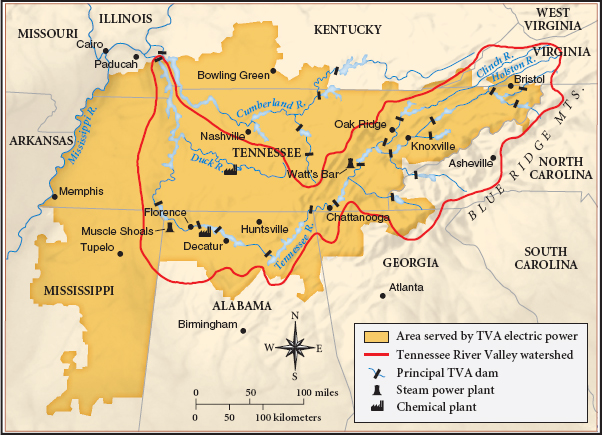

Tennessee Valley Authority The most extensive New Deal environmental undertaking was the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), which Roosevelt saw as the first step in modernizing the South. Funded by Congress in 1933, the TVA integrated flood control, reforestation, electricity generation, and agricultural and industrial development. The dams and their hydroelectric plants provided cheap electric power for homes and factories as well as ample recreational opportunities for the valley’s residents. The massive project won praise around the world (Map 23.5).

The TVA was an integral part of the Roosevelt administration’s effort to keep farmers on the land by enhancing the quality of rural life. The Rural Electrification Administration (REA), established in 1935, was also central to that goal. Fewer than one-tenth of the nation’s 6.8 million farms had electricity. The REA addressed this problem by promoting nonprofit farm cooperatives that offered loans to farmers to install power lines. By 1940, 40 percent of the nation’s farms had electricity; a decade later, 90 percent did. Electricity brought relief from the drudgery and isolation of farm life. Electric irons, vacuum cleaners, and washing machines eased women’s burdens, and radios brightened the lives of the entire family. Along with the automobile and the movies, electricity broke down the barriers between urban and rural life.

Grand Coulee As the nation’s least populated but fastest-growing region, the West benefitted enormously from the New Deal’s attention to the environment. With the largest number of state and federal parks in the country, the West gained countless trails, bridges, cabins, and other recreational facilities, laying the groundwork for the post-World War II expansion of western tourism. On the Colorado River, Boulder Dam (later renamed Hoover Dam) was completed in 1935 with Public Works Administration funds; the dam generated power for the region’s growing cities such as Las Vegas, Los Angeles, and Phoenix.

The largest project in the West, however, took shape in an obscure corner of Washington State, where the PWA and the Bureau of Reclamation built the Grand Coulee Dam on the Columbia River. When it was completed in 1941, Grand Coulee was the largest electricity-producing structure in the world, and its 150-mile lake provided irrigation for the state’s major crops: apples, cherries, pears, potatoes, and wheat. Inspired by the dam and the modernizing spirit of the New Deal, folk singer Woody Guthrie wrote a song about the Columbia. “Your power is turning our darkness to dawn,” he sang, “so roll on, Columbia, roll on!”

New Deal projects that enhanced people’s enjoyment of the natural environment can be seen today throughout the country. CCC and WPA workers built the famous Blue Ridge Parkway, which connects the Shenandoah National Park in Virginia with the Great Smoky Mountains National Park in North Carolina. In the West, government workers built the San Francisco Zoo, Berkeley’s Tilden Park, and the canals of San Antonio. The Civilian Conservation Corps helped to complete the East Coast’s Appalachian Trail and the West Coast’s Pacific Crest Trail through the Sierra Nevada. In state parks across the country, cabins, shelters, picnic areas, lodges, and observation towers stand as monuments to the New Deal ethos of recreation coexisting with nature.

IDENTIFY CAUSES