Rising Discontent

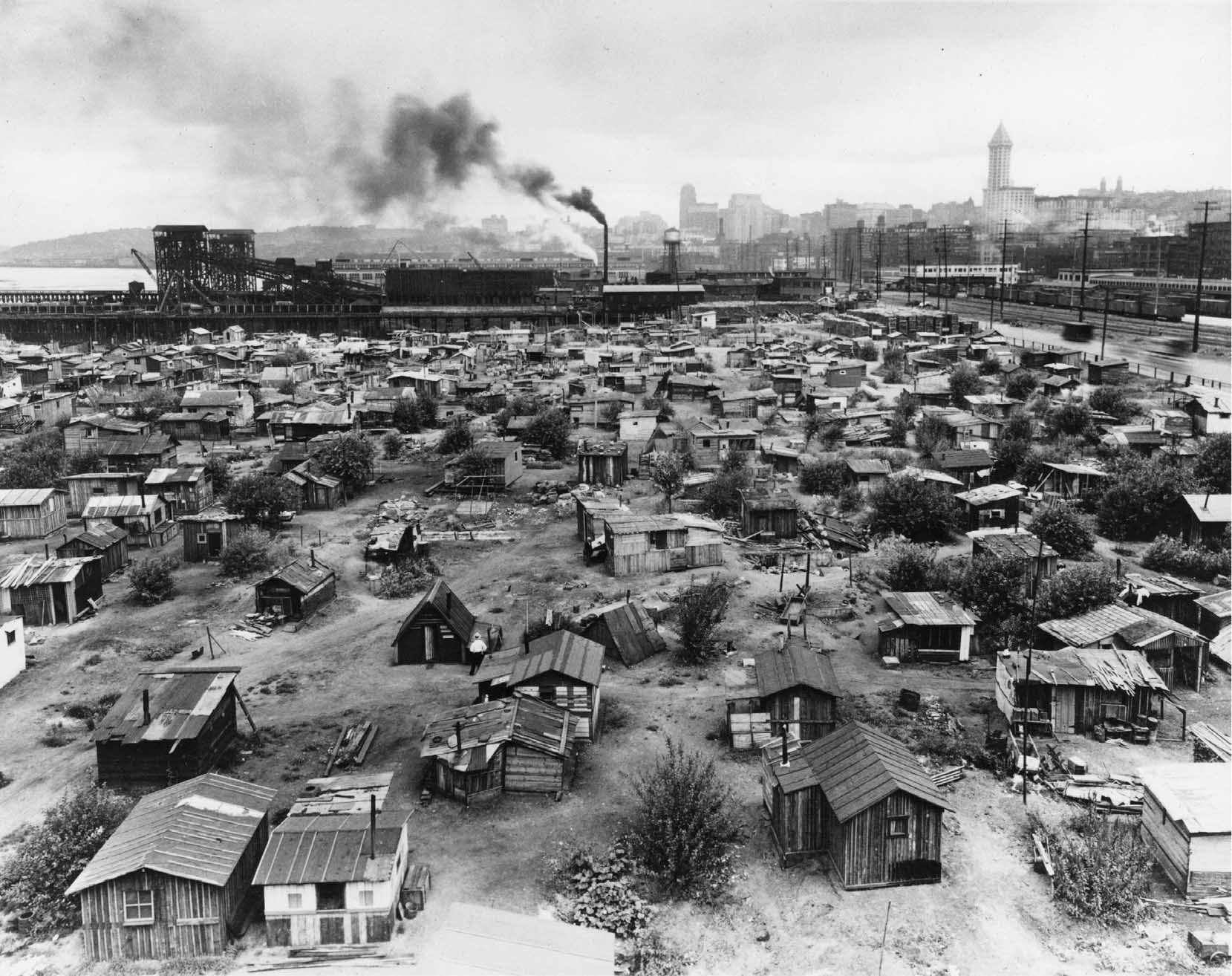

As the depression deepened, the American vocabulary now included the terms Hoovervilles (shantytowns where people lived in packing crates) and Hoover blankets (newspapers). Bankrupt farmers banded together to resist the bank agents and sheriffs who tried to evict them from their land. To protest low prices for their goods, in the spring of 1932 thousands of midwestern farmers joined the Farmers’ Holiday Association, which cut off supplies to urban areas by barricading roads and dumping milk, vegetables, and other foodstuffs onto the roadways. Agricultural prices were so low that the Farmers’ Holiday Association favored a government-supported farm program.

In the industrial sector, layoffs and wage cuts led to violent strikes. When coal miners in Harlan County, Kentucky, went on strike over a 10 percent wage cut in 1931, the mine owners called in the state’s National Guard, which crushed the union. A 1932 confrontation between workers and security forces at the Ford Motor Company’s giant River Rouge factory outside Detroit left five workers dead and fifty with serious injuries. A photographer had his camera shot from his hands, and fifteen policemen were clubbed or stoned. Whether on farms or in factories, those who produced the nation’s food and goods had begun to push for a more aggressive response to the nation’s economic troubles.

Veterans staged the most publicized — and most tragic — protest. In the summer of 1932, the Bonus Army, a determined group of 15,000 unemployed World War I veterans, hitchhiked to Washington to demand immediate payment of pension awards that were due to be paid in 1945. “We were heroes in 1917, but we’re bums now,” one veteran complained bitterly. While their leaders unsuccessfully lobbied Congress, the Bonus Army set up camps near the Capitol building. Hoover called out regular army troops under the command of General Douglas MacArthur, who forcefully evicted the marchers and burned their main encampment to the ground. When newsreel footage showing the U.S. Army attacking and injuring veterans reached movie theaters across the nation, Hoover’s popularity plunged. In another measure of how the country had changed since the 1890s, what Americans had applauded when done to Coxey in 1894 was condemned in 1932.