Financing the War

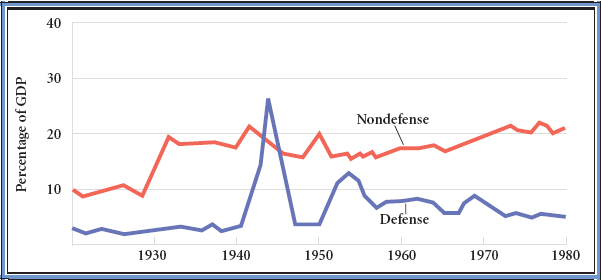

Defense mobilization, not the New Deal efforts of the 1930s, ended the Great Depression. Between 1940 and 1945, the annual gross national product doubled, and after-tax profits of American businesses nearly doubled (America Compared). Federal spending on war production powered this advance. By late 1943, two-thirds of the economy was directly involved in the war effort (Figure 24.1). The government paid for these military expenditures by raising taxes and borrowing money. The Revenue Act of 1942 expanded the number of people paying income taxes from 3.9 million to 42.6 million. Taxes on personal incomes and business profits paid half the cost of the war. The government borrowed the rest, both from wealthy Americans and from ordinary citizens, who invested in long-term treasury bonds known as war bonds.

Financing and coordinating the war effort required far-reaching cooperation between government and private business. The number of civilians employed by the government increased almost fourfold, to 3.8 million — a far higher rate of growth than that during the New Deal. The powerful War Production Board (WPB) awarded defense contracts, allocated scarce resources — such as rubber, copper, and oil — for military uses, and persuaded businesses to convert to military production. For example, it encouraged Ford and General Motors to build tanks rather than cars by granting generous tax advantages for re-equipping existing factories and building new ones. In other instances, the board approved “cost-plus” contracts, which guaranteed corporations a profit, and allowed them to keep new steel mills, factories, and shipyards after the war. Such government subsidies of defense industries would intensify during the Cold War and continue to this day.

To secure maximum production, the WPB preferred to deal with major enterprises rather than with small businesses. The nation’s fifty-six largest corporations received three-fourths of the war contracts; the top ten received one-third. The best-known contractor was Henry J. Kaiser. Already highly successful from building roads in California and the Hoover and Grand Coulee dams, Kaiser went from government construction work to navy shipbuilding. At his shipyard in Richmond, California, he revolutionized ship construction by applying Henry Ford’s techniques of mass production. To meet wartime production schedules, Kaiser broke the work process down into small, specialized tasks that newly trained workers could do easily. Soon, each of his work crews was building a “Liberty Ship,” a large vessel to carry cargo and troops to the war zone, every two weeks. The press dubbed him the Miracle Man.

Central to Kaiser’s success were his close ties to federal agencies. The government financed the great dams that he built during the depression, and the Reconstruction Finance Corporation lent him $300 million to build shipyards and manufacturing plants during the war. Working together in this way, American business and government turned out a prodigious supply of military hardware: 86,000 tanks; 296,000 airplanes; 15 million rifles and machine guns; 64,000 landing craft; and 6,500 cargo ships and naval vessels. The American way of war, wrote the Scottish historian D. W. Brogan in 1944, was “mechanized like the American farm and kitchen.” America’s productive industrial economy, as much as or more than its troops, proved the decisive factor in winning World War II.

The system of allotting contracts, along with the suspension of antitrust prosecutions during the war, created giant corporate enterprises. By 1945, the largest one hundred American companies produced 70 percent of the nation’s industrial output. These corporations would form the core of what became known as the nation’s “military-industrial complex” during the Cold War (discussed in Chapter 25).

TRACE CHANGE OVER TIME